“Action/Abstraction: Pollock, De Kooning and American Art, 1940-1976” au Jewish Museum, NY

Installation view of “Action/Abstraction: Pollock, de Kooning, and American Art, 1940-1976” at the Jewish Museum. (Photo: Julien Jourdes for The New York Times)

Roberta Smith writes: Art is long, art criticism is often very, very brief, its Internet afterlife notwithstanding. Its viability relies on a mixture of prose style, sound-bite-able concepts, timing and its ability to clarify visual experience. Naming a major art movement can also help. Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg met many of these requirements. Tenacious Jewish intellectuals formed by the leftist ferment of New York between the wars, both became disillusioned socialists who turned to art and especially the new painting they saw emerging around them. In the late 1940s, and ’50s, they were Abstract Expressionism’s most prominent champions, often in diametric opposition to each other. Cordial mutual dislike was their bond.

Rosenberg and Greenberg are reunited in “Action/Abstraction: Pollock, De Kooning and American Art, 1940-1976,” a fast-moving exhibition at the Jewish Museum. Their names aren’t on the marquee, but their rivalry provides the structure for this exceedingly handsome if somewhat capricious show. (Photo: Julien Jourdes for The New York Times)

“White and Hot” (1967) by Barnett Newman

Greenberg especially personified the arrogant critic brilliantly defining and then relentlessly pursuing his agenda. Writing with a clear, Olympian style that nonetheless had intonations of a sportscaster calling a horse race, he formulated a narrowing end game for modernism: All art mediums would remain discrete while being reduced, by successive innovations, to their essences. (Photo: Saint Louis Art Museum, Barnett Newman Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

An untitled work of Jackson Pollock from 1951.

For painting, this meant abstraction, flatness and the elimination of touch. Pollock, dancing around the canvas flinging paint, was his ideal. At least until the late 1950s, when he decided that Newman’s and Rothko’s expanses of color pointed to the next big thing: Color Field painting. (Photo: Portland Art Museum, The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Willem de Kooning’s “Gotham News” (1955)

Rosenberg famously characterized the painter’s canvas “as an arena in which to act” and found his ideal in De Kooning, whose canvases were thick with loaded brushwork, alive with elegant angst and widely influential. Rosenberg gave the new style its first name: Action Painting, pinpointing a performative aspect in postwar art that is still being explored. (Photo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

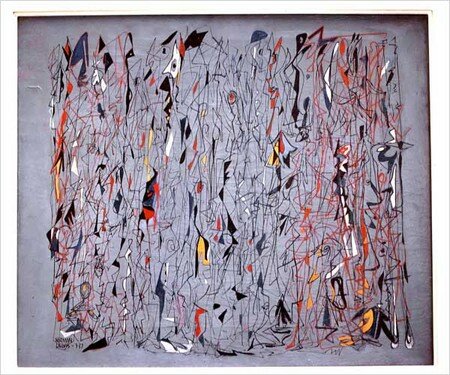

“Twilight Sounds” (1947) by Norman Lewis

“Action/Abstraction” is not so much a historical survey as a series of lavishly illustrated talking points. It proceeds through various pairings and groupings that illuminate who Greenberg and Rosenberg promoted or ignored, where they differed or overlapped. Their oversights included much sculpture (excepting David Smith) and most painters who were not white and male, as indicated by a section titled “Blind Spots” that contains works by Norman Lewis, Grace Hartigan and Lee Krasner, Pollock’s wife. (Photo: Saint Louis Art Museum, courtesy Bill Hodges Gallery, New York)

The first gallery, a tour de force, lays out Abstract Expressionism’s greatest artistic rivalry in four works by Pollock and three by De Kooning. Pollock’s 1952 “Convergence” virtually explodes off the back wall, its imperious flings of red, yellow, blue and white pushed forward by a calligraphic undergrowth of black. The modest gallery pressurizes the large painting, but pressure becomes it. (Photo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo/The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

“Woman” (1949-50) by Willem de Kooning

The beginning of De Kooning’s many-splendored career is represented by increasingly fraught surfaces: the inky darks and searing whites of “Black Friday,” of 1948; the monstrous “Woman” of 1949-50 and the exultantly agitated “Gotham News” of 1955. (Photo: Weatherspoon Art Museum/The Willem de Kooning Foundation, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

“Liver and the Cock’s Comb” (1944) by Arshile Gorky

While sharing burning colors, the vibrating forms of Arshile Gorky’s hallucinatory “Liver and the Cock’s Comb” of 1944 clash with the martial push-pull of Han Hofmann’s “Sanctum Sanctorum” of 1961. (Photo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, N.Y/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Hans Hofmann’s “Sanctum Sanctorum“ (1962)

The similarities among these artworks exceed the differences, raising the falseness of dichotomies. Were Greenberg’s and Rosenberg’s views really so far apart, or did they just find certain aspects of art easier to talk about than others? (Photo: Berkeley Art Museum, Renate, Hans & Maria Hofmann Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

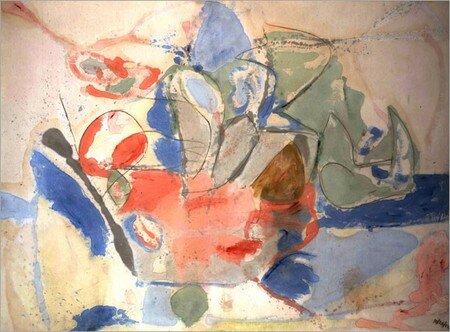

The show’s second half begins with ephemera reflecting the popular acceptance of Abstract Expressionism. Neither Greenberg nor Rosenberg was able to fully accept the art that followed, but here the similarities end. Greenberg more or less squandered his reputation in his relentless promotion of Color Field painting and related sculpture., which is represented by Helen Frankenthaler’s breakthrough stain painting “Mountains and Sea” of 1952. (Photo: Helen Frankenthaler Foundation)

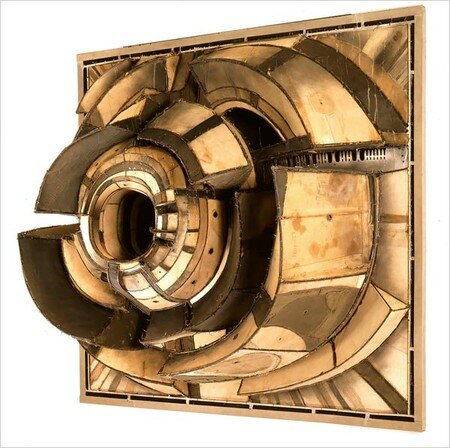

An untitled 1962 work by Lee Bontecou

Rosenberg, meanwhile, kept looking, and writing. With his notion of new art as an “anxious object,” which he coined in the early 1960s, he expanded his ideas of action and painterly gesture to the early work of younger artists like Claes Oldenburg, Peter Saul, Jasper Johns and Lee Bontecou, all of whom are represented here. (Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston /Lee Bontecou, courtesy of Knoelder & Company, New York)

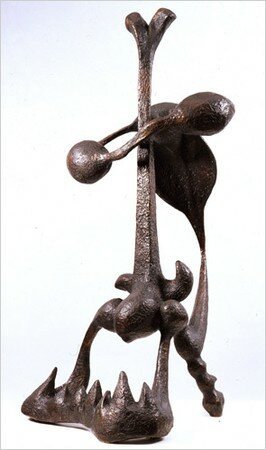

Herbert Ferber’s “Surrational Zeus II” (1947). (The Jewish Museum/Herbert Ferber Estate)

“Action/Abstraction: Pollock, De Kooning and American Art, 1940-1976” is at the Jewish Museum through Sept. 21; 1109 Fifth Avenue, at 92nd Street, (212) 423-3271.

Lire l'article "Rivalry Played Out on Canvas and Page" de Roberta Smith http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/02/arts/design/02acti.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_65a1d8_telechargement-31.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_3b1c51_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_2a8420_437713933-1652609748842371-16764302136.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_3f6edc_438868891-1652442212192458-70192626099.jpg)