"Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur' @ the Seattle Asian Art Museum

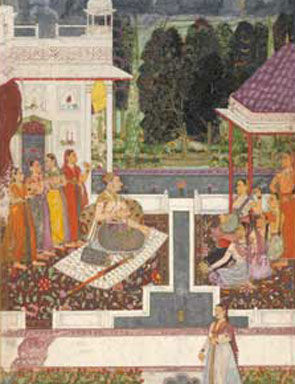

Maharaja Jaswant Singh I at a Music Performance during a Monsoon, Jodhpur, ca. 1670, Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, H x W: 26.8 x 17.4 cm. ELS2008.2.4. Credit: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, Felton Bequest, 1980.

SEATTLE, WA.- The pioneering exhibition Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur presents little known, large-scale images from the 17th-19th centuries that convey an unsurpassed intensity of artistic vision in Rajasthan art. During an international tour, Garden and Cosmos will be on view in the Seattle Asian Art Museum’s South Galleries Jan. 29-April 26, 2009.

Marwar-Jodhpur, the largest of the former Rajput kingdoms (in the modern state of Rajasthan in northwest India), was ruled by the Rathore Rajputs, a princely caste of warriors who became great patrons of art in the 17th to19th centuries. Here, the great fort Mehrangarh overlooks the capital city of Jodhpur, where it served generations of rulers not only as a military base but also as a complex of temples, courtyards and palaces and a center of music and art.

The elaborate paintings on view in Garden and Cosmos come to Seattle from the Mehrangarh fort's present-day museum, thanks to the generosity of the Mehrangarh Trust, headed by Maharaja Gaj Singh II of Jodhpur, lender of the fifty-five paintings from the desert palace at Nagaur that form the centerpiece of the exhibition. Created for the private enjoyment of the Jodhpur maharajas, these paintings include thirty-three richly-adorned, four-foot-wide folios from 19th-century "monumental manuscripts," which demonstrate how yogic philosophy and practice changed the focus of art patronage, resulting in a surprisingly "modern," sublimely minimal aesthetic. Ten 17th-century Jodhpur paintings borrowed from museum collections in India, Europe, Australia and the U.S. reveal the idiom from which these innovations of later Jodhpur painting emerged. Despite striking innovations in scale, subject matter and style, virtually none of the paintings in Garden and Cosmos have been published and most have been seen by only a handful of scholars since their creation.

The clear development of court painting in this region from the 17th through 19th centuries is explicit in the 57 total works on view, and specifically traces the area’s political history, as its rule changed hands from the early 18th through mid 19th centuries -- often by means of scandalous usurpation or divine inspiration.

Painting in a palette of rich colors and elaborately decorative patterns, court artists depicted Maharaja Bakhat Singh (reigned 1725-51) sporting with his harem in fantastic gardens. Painters replaced images of royal luxury with visions of heavenly landscapes populated by Hindu deities such as Krishna and Rama during Maharaja Vijai Singh's reign (reigned 1752-93). Artists working for Vijai Singh's grandson Maharaja Man Singh (reigned 1803-1843) were challenged to create images of metaphysical concepts and yoga narratives, such as the origins of the cosmos, reflecting the ruler’s devotion to an esoteric yogic tradition.

GARDEN AND COSMOS

Garden and Cosmos is divided into thematic sections devoted to the garden and cosmos themes, with an introductory gallery revealing the history of the kingdom of Marwar-Jodhpur and the origins of its court painting traditions in the 17th century.

THE ORIGINS OF JODHPUR COURT PAINTING

Between the 13th and the 17th centuries, the Rathore clan leaders transformed from regional rulers into cosmopolitan maharajas, or great kings. Five 17th-century paintings track this transformation by revealing how the atelier synthesized a local, spontaneous style with the sophisticated court style of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857) to create a uniquely Marwar-Jodhpur idiom. Small in size, these royal portraits and musical theme paintings (ragamala) presage -- and help the viewer to fully appreciate -- the innovative directions taken by the atelier in the following centuries.

GARDENS FOR ROYAL PLEASURE: MAHARAJA BAKHAT SINGH

A recently rediscovered cache of paintings reveal that the aesthetic of the garden first emerged under Maharaja Bakhat Singh (1725-51) at Ahhichatragarh Fort in Nagaur on the northern border of Marwar. Bakhat Singh was an exemplary ruler, but his reputation was permanently stained when he murdered his father in order to gain the throne of Nagaur.

Bakhat Singh transformed the arid region of Nagaur, into a garden paradise by rebuilding its palaces and creating a sophisticated water-harvesting system. Eleven paintings accurately depict the architectural setting and express Bakhat Singh's sensuous delight in the opulent garden-palaces. Many paintings also depict musical performances.

THE GARDEN IN THE DESERT

The exhibition will also feature a splendid embroidered tent canopy from the Marwar ancestral collection. Exuberantly adorned on its interior with silk-embroidered blossoms on scrolling vines, the tent canopy recreates the virtual gardens that the maharajas enjoyed when they made camp in remote areas of the desert kingdoms while on military campaigns or religious pilgrimages. The floral pattern, which recurs in paintings of gardens throughout the exhibition, epitomizes the Marwar aesthetic of the garden.

GARDENS FOR DIVINE PLAY: MAHARAJA VIJAI SINGH

Maharaja Vijai Singh, the son of Bakhat Singh, ruled Marwar for 41 years (1752-93). Vijai Singh's atelier created the "monumental manuscript" genre for sacred texts relating the exploits of Krishna, Rama and the great Goddess Durga. While Vijai Singh's court artists continued to depict gardens and palaces in the rich pastel colors employed at Nagaur in Bakhat Singh's reign (1725-51), their grand vision expanded and transformed the earthly court into expansive sacred landscapes that charm and delight with narrative verve and compositional ingenuity.

KINGDOM AND COSMOS: MAHARAJA MAN SINGH

The grandson of Vijai Singh, Man Singh credited his near miraculous ascension to the Marwar throne to the divine intervention of Jallandharnath, an immortal practitioner of hatha yoga (mahasiddha). Originating in the 12th-13th centuries by India’s Nath religious sect, the Hatha Yoga of Man Singh and other Nath disciples was much broader than the modern conception of the practice, comprising meditative and somatic rituals performed by mortals in order to achieve immortality or supernatural powers. Man Singh sought, through his religious devotion, to undermine the hereditary nobility, replacing it with a divinely legitimized sectarian elite. He would use his art patronage to illustrate and underscore the legitimate role of these ascetics, gurus and disciples within the political history of Marwar-Jodhpur.

Man Singh commissioned more than 1,000 paintings expressing the sacred power of the Nath mahasiddhas and their metaphysics. Garden and Cosmos includes about two dozen of these spectacular paintings, which present intense, almost hallucinatory images of enormous conceptual sophistication and visual élan. Monumental paintings in this section of the exhibition represent profound subjects with visionary intensity. Large fields of gold map the cosmos and its emergence from the formless void in some works, while others incorporate intricately realized bodies and cosmic landscapes with shimmering silver rivers. The subject matter ranges from the origins of the cosmos and the immaterial essence of being Brahman, to shimmering chakras (energy centers), mandalas (cosmic maps) and asanas (yoga postures).These imposing works often employ unexpected changes of scale, subdivisions of the page and multiple, successive narratives. Such cosmic and divine compositions had never before attempted by Indian court painters.

Maharaja Bakhat Singh and Zenana Women, Savor the Moonlight Evening. Attributed here to “Artist 3”, Nagaur, ca. 1748–50, Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, H x W: 45.4 x 63.5 cm, ELS2008.2.75 (Cat. 19), Image Credit: Mehrangarh Museum Trust. (Detail)

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F96%2F119589%2F129836760_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F33%2F99%2F119589%2F129627838_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F83%2F119589%2F129627729_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F37%2F119589%2F129627693_o.jpg)