'Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler' @ British Museum

Turquoise mosaic of a double-headed serpent. Mexica/Mixtec, 15th–16th century AD. From Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum

LONDON.- Completing its series of exhibitions exploring power and empire, the British Museum focuses on the last elected Aztec Emperor, Moctezuma II. Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler is the first exhibition to examine the semi-mythical status of Moctezuma and his legacy today. Loans of iconic material from Mexico and Europe will be displayed, most for the first time in this country. The exhibition anticipates the anniversaries in 2010 of the Independence of Mexico (1810) and of the Mexican Revolution (1910).  Moctezuma (reigned 1502-1520) inherited and then consolidated Aztec control over a politically complex empire that by the early 16th century stretched from the shores of Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico. Moctezuma was regarded as a semi- divine figure by his subjects charged with the task of interceding with the gods. As a battle-hardened general he was appointed supreme military commander and headed the two most prestigious warriors orders: the eagle and jaguar warriors. He was elected as Ruling Lord (huey tlatoani) in 1502, built a new palace in the heart of Tenochtitlan (modern day Mexico City) and restructured the court. The arrival of the Spanish, during Moctezuma’s reign, witnessed the collapse of the native world order and the imposition of a new civilization that gave birth to modern Mexico. (Image: Portrait of Moctezuma by Antonio Rodriguez © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Moctezuma (reigned 1502-1520) inherited and then consolidated Aztec control over a politically complex empire that by the early 16th century stretched from the shores of Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico. Moctezuma was regarded as a semi- divine figure by his subjects charged with the task of interceding with the gods. As a battle-hardened general he was appointed supreme military commander and headed the two most prestigious warriors orders: the eagle and jaguar warriors. He was elected as Ruling Lord (huey tlatoani) in 1502, built a new palace in the heart of Tenochtitlan (modern day Mexico City) and restructured the court. The arrival of the Spanish, during Moctezuma’s reign, witnessed the collapse of the native world order and the imposition of a new civilization that gave birth to modern Mexico. (Image: Portrait of Moctezuma by Antonio Rodriguez © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Uniquely, the exhibition will present a biographical narrative of Moctezuma II and reveal the dual nature of his reputation. On the one hand, he is recognised as a successful and cunning warrior but he is also widely perceived as a tragic figure who ceded his empire to foreigners. Divergent interpretations of his mysterious death will be re-examined in the exhibition.

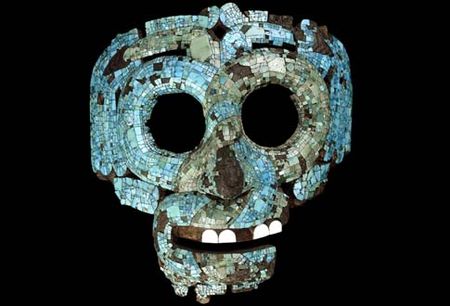

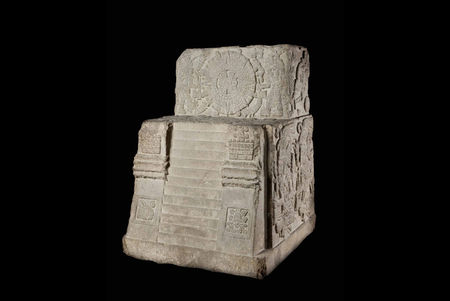

The exhibition will present masterpieces of Aztec culture including the impressive stone monument known as the Teocalli of Sacred Warfare, amongst other works commissioned by Moctezuma himself which bear his image and his name glyph. An exquisite turquoise mask and goldwork will showcase the consummate craftsmanship of artisans employed in the Aztec court and masterly paintings known as “Enconchados” (oil paintings on wooden panels with inlaid Mother of Pearl detail) portray the events of the conquest in vivid detail. Idealized European portraits of Moctezuma and stunning colonial Codices have helped shape our interpretations of Moctezuma and his world.

The exhibition  The exhibition tells the story of Moctezuma II, the last elected ruler of the Aztecs, more correctly known now as the Mexica. From 1502 until 1520 he presided over a large empire embracing much of what is today central Mexico. This exhibition examines his life, reign and controversial death during the Spanish conquest. The Spanish arrived on Mexican shores in 1519, led by Hernan Cortes. They were initially well received in the Aztec capital, but distrust and violence ensued. Moctezuma was captured and met his death shortly afterwards. Overcoming resistance, the Spanish went on to conquer his empire. Moctezuma’s life and dramatic death are explained through objects ranging, from sculpture, gold and mosaic items to codices and European paintings. The objects are drawn from Mexican, European, US collections and the British Museum’s own collection. (Image: Nose Ornament, AD 1400 – 1521, Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum)

The exhibition tells the story of Moctezuma II, the last elected ruler of the Aztecs, more correctly known now as the Mexica. From 1502 until 1520 he presided over a large empire embracing much of what is today central Mexico. This exhibition examines his life, reign and controversial death during the Spanish conquest. The Spanish arrived on Mexican shores in 1519, led by Hernan Cortes. They were initially well received in the Aztec capital, but distrust and violence ensued. Moctezuma was captured and met his death shortly afterwards. Overcoming resistance, the Spanish went on to conquer his empire. Moctezuma’s life and dramatic death are explained through objects ranging, from sculpture, gold and mosaic items to codices and European paintings. The objects are drawn from Mexican, European, US collections and the British Museum’s own collection. (Image: Nose Ornament, AD 1400 – 1521, Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Introduction

According to myth, the ‘Aztecs’ were the ruling lords in the land of ‘Aztlan’. One subject group managed to escape their rule and began a long migration, adopting the name ‘Mexica’. The Mexica settled in the Basin of Mexico, founding their capital Tenochtitlan in about 1200. They spoke Nahuatl, one of many indigenous languages. ‘Aztec’ has been popularly but incorrectly used to describe the Mexica civilisation since the 1800s. The name ‘Mexica’ (pronounced ‘Mesheeka’) was recognised by the conquering Spanish, hence the name for modern Mexico.

Moctezuma’s fame is more celebrated in Europe than in Mexico itself. The exhibition opens with an idealised European portrait of Moctezuma from the 1600s. It is accompanied by a stone box that was owned by Moctezuma. This bears his identifying name-glyph, which will be encountered again in later sections. The exhibition will reveal what we know of Moctezuma’s life before the arrival of the Spanish.

The Aztecs (Mexica)  The Mexica capital city, Tenochtitlan, was located on an island set in Lake Tetzcoco in the Basin of Mexico. The first section of the exhibition looks at the foundation myth and features objects relating to this mythology, including a greenstone heart and a large eagle sculpture. From its beginnings in about 1300, Tenochtitlan rapidly grew to become a thriving metropolis. Moctezuma was the last in a long line of Aztec rulers and lived in a palace adjacent to the main ceremonial precinct in the heart of Tenochtitlan. His immediate predecessor was his uncle Ahuitzotl. (Image: Teocalli of Sacred Warfare, AD 1507, Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum)

The Mexica capital city, Tenochtitlan, was located on an island set in Lake Tetzcoco in the Basin of Mexico. The first section of the exhibition looks at the foundation myth and features objects relating to this mythology, including a greenstone heart and a large eagle sculpture. From its beginnings in about 1300, Tenochtitlan rapidly grew to become a thriving metropolis. Moctezuma was the last in a long line of Aztec rulers and lived in a palace adjacent to the main ceremonial precinct in the heart of Tenochtitlan. His immediate predecessor was his uncle Ahuitzotl. (Image: Teocalli of Sacred Warfare, AD 1507, Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Moctezuma as ruler

Moctezuma is introduced through his coronation stone. We will explain how, once nominated to succeed his uncle, he had to prove himself through military campaign before being formally invested. At his coronation in 1502 he was given the insignia of office including treasured turquoise and gold items of personal adornment. Moctezuma built a new palace to administer the empire and lived there with his wives, children and the courtly entourage. A number of architectural fragments from the palace excavations will be on display.

Religion and the gods

Moctezuma was a vital intermediary with the Mexica gods and was himself regarded by his subjects as a semi-divine figure. He worshipped at the Great Temple, a huge stepped pyramid in the heart of the ritual centre of Tenochtitlan. We will display a model that will show the Temple and other ritual buildings. Moctezuma would have carried out blood-letting rituals, and ordered the sacrifice of captives. We will examine the most important gods, including Quetzalcoatl. It is a popularly held belief that Moctezuma considered Cortes to be a personification of the returning deity Quetzalcoatl, although this has been challenged by recent scholarship. The end of the section focuses on the New Fire Ceremony. This marked the end of a 52-year period in the Mexica calendrical cycle that occurred during Moctezuma’s reign and can be dated to 1508.

Warfare and empire

Moctezuma was a formidable warrior and head of the Mexica army. We will display a range of ceremonial weaponry as well as an imposing monument sculpted with Mexica warriors. Particularly important was the site of Malinalco, where the elite Jaguar and Eagle warriors were based. Moctezuma consolidated the Mexica empire and secured tribute, or taxes, that poured into Tenochtitlan. Exacting tribute in the form of raw materials or crafted goods contributed to the opulence of the court but meant that Moctezuma was feared and resented among subject towns.

Conquest  The Spaniard Hernan Cortes landed on the coast in 1519 along with a few hundred men. At the same time, the Mexica are said to have witnessed strange omens and signs that are later depicted in the codices. Moctezuma sent emissaries to the coast with gifts for Cortes. Cortes forged alliances with bitter rival of the Mexica in the course of his march to Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma greeted Cortes but made the fatal mistake of allowing the Spanish into Tenochtitlan and housing them in a palace. The Spanish captured Moctezuma and unrest broke out in the city following a massacre of Mexica nobles by the Spanish. Shortly afterwards Moctezuma died – and it is widely believed that he was stoned to death by his own people. However, other sources claim that he was in fact secretly murdered by the Spanish. The main events of the conquest are documented by a series of colonial paintings. (Image: Gold Turtle Necklace, AD 1400 – 1521, Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum)

The Spaniard Hernan Cortes landed on the coast in 1519 along with a few hundred men. At the same time, the Mexica are said to have witnessed strange omens and signs that are later depicted in the codices. Moctezuma sent emissaries to the coast with gifts for Cortes. Cortes forged alliances with bitter rival of the Mexica in the course of his march to Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma greeted Cortes but made the fatal mistake of allowing the Spanish into Tenochtitlan and housing them in a palace. The Spanish captured Moctezuma and unrest broke out in the city following a massacre of Mexica nobles by the Spanish. Shortly afterwards Moctezuma died – and it is widely believed that he was stoned to death by his own people. However, other sources claim that he was in fact secretly murdered by the Spanish. The main events of the conquest are documented by a series of colonial paintings. (Image: Gold Turtle Necklace, AD 1400 – 1521, Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Moctezuma in history

After Moctezuma’s death, the Spanish conquered the Mexica Empire with assistance from Moctezuma’s enemies. We will display items that were later repurposed by the Spanish, such as a serpent sculpture that was inverted to form a baptismal font. Moctezuma’s daughters Isabel and Mariana and son Pedro survived the conquest. Codices show how they went to Spain and intermarried with the nobility there. Moctezuma has an ambivalent reputation within Mexico today, but his fame lived on as a figure of fascination within Europe. The exhibition ends with European portraits of Moctezuma. There depict him as a once-proud warrior and tragic figure who surrendered his empire but whose fame live on.

The exhibition will be the first ever in Europe focusing on the great age of Mexican printmaking in the first half of the twentieth century. Between 1910 and 1920 the country was convulsed by the first socialist revolution, from which emerged a strong left-wing government that laid great stress on art as a vehicle for promoting the values of the revolution. This led to a pioneering programme to cover the walls of public buildings with vast murals, and later to setting up print workshops to produce works for mass distribution and education. Some of the finest of these prints were produced by the three great men of Mexican art of the period: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The exhibition will also include earlier works around the turn of the century by the popular engraver, José Guadalupe Posada, who was adopted by the revolutionaries as the archetypal printmaker who worked for the people, and whose macabre dances of skeletons have always fascinated Europeans.

24 September 2009–24 January 2010

Mosaic mask of Tezcatlipoca. Mexica/Mixtec, 15th–16th century AD. From Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum

Knife with a mosaic handle and a chalcedony blade. Mexica/Mixtec, 15th–16th century AD. From Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum

Mosaic mask of Quetzalcoatl. Mexica/Mixtec, 15th–16th century AD. From Mexico © The Trustees of the British Museum

Turquoise Mosaic Mask, Aztec/Mixtec AD 1400-1521, Mexico. Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum.

Stone bust of Quetzalcoatl. Aztec, A.D. 1300-1521 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Seated figure made of stone © The Trustees of the British Museum

Stone from Temple. Photo Michel Zabe/INAH.

Head of Serpent. Photo: Michel Zabe/INAH.

Cactus. Photo: Michel Zabe/INAH.

Altar of the warriors, c. 1510, Mexica. Basalt, 118 x 161 x 65cm. On loan from Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City.

Teocalli of Sacred Warfare, AD 1507, Mexico. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes - Institutio Nacional de Antropologia e Historia.

Hackmack box, AD 1506, Mexico. Copyright Hamburg Museum fur Volkerkunde. Photo John Williams.

Gold Turtle Necklace, AD 1400-1521, Mexico. Copyright Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, DC.

Gold finger ring, 1200 - 1521, gold pendant of human face and warrior-ruler figurine with ritual regalia. Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum.

Pendant, c. 1200-1521, Mixtec-Zapotec. Gold with silver and copper. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Finger ring made of cast gold with a feline head, 1300-1521, Mixtec. Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum.

Portrait of Moctezuma by Antonio Rodriguez. Oil on canvas 1680-97. Museo degli Argenti, Florence. Copyright Su concessione del Ministero per I Beni e le Attivit Culturali.

Fan. Photo: Michel Zabe/INAH.

(AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis)

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F79%2F90%2F119589%2F127860843_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F81%2F95%2F119589%2F127822755_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F13%2F19%2F119589%2F122390641_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F24%2F26%2F119589%2F117560837_o.jpg)