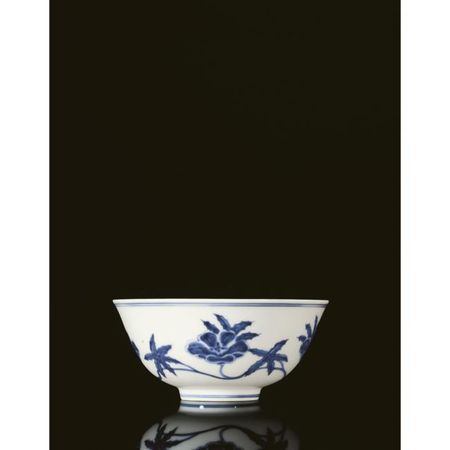

A superb blue and white palace bowl, mark and period of Chenghua

A superb blue and white palace bowl, mark and period of Chenghua

masterfully potted with smooth rounded sides, gracefully rising from a tapered foot to a slightly flared rim, superbly painted in characteristic soft tones of cobalt-blue in outlines infilled with wash, the exterior with a gently undulating meander of musk mallow, the four blossoms in full bloom with tender flaring petals, interspersed with star-shaped leaves, each bloom with a leaf delicately tucked and partially concealed behind, all between double line bands at the rim and foot, the interior with a central medallion enclosing a single flower head within a double circle, encircled by a similarly exquisite musk mallow meander to that on the exterior bearing five blooms and pointed leaves, beneath a double-line band at the rim, covered overall in a thick unctuous glaze fired to a waxy finish, the base inscribed with the four-character mark within double circles. 14.7 cm., 5 3/4 in. Est. 32,000,000—42,000,000 HKD - Sold 36,500,000 HKD

PROVENANCE: Christie's Hong Kong, 20 March 1990, lot 523. (IIlustrated on the cover).

Christie's Hong Kong, 27th April 1997, lot 73.

Sotheby's Hong Kong, 7th October 2006, lot 908.

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Li Zhengzhong and Zhu Yuping, Taoci yanjiu jiansheng congshu, 3: Zhongguo qinghua ci, Taipei, 1993, fig.101.

NOTE:

Muted Elegance - A Superb Chenghua Palace Bowl

by Regina Krahl

Chenghua porcelains are the rarest Chinese Imperial porcelains, and this rarity can hardly be stressed enough. Liu Xinyuan graphically describes the volume of fragments recovered from the site of the Ming Imperial kilns, where the Chenghua (AD 1465 – 1487) fragments equal less than half those unearthed from the Xuande stratum (AD 1426 – 1435), even though the latter period was so much shorter.1 The scarcity of sherds at the kiln site is mirrored by the rarity of surviving examples. Of those by far the greatest number is preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taiwan, and in Museums in mainland China. Of the remaining examples, most are today in museum collections. Only some two dozen Chenghua pieces of any type are recorded to be in private hands.2

The porcelains of this period were always greatly admired and for good reason. They display a very distinct character both in terms of their material and their style of decoration. The decoration is of a striking artlessness and immediacy that focuses attention on the material. The cobalt pigment is much more even than it was in the Xuande period, without any 'heaping and piling'; its attractive soft tone is one of the trademarks of Chenghua blue-and-white. Chenghua glazes are arguably the finest ever achieved at Jingdezhen. Unlike the crisp and glossy glazes of the best Xuande wares, those of the Chenghua reign are more muted, covering the blue design with a most delicate veil. Their smooth surface texture is unrivalled in its tactility. The sensual pleasure of the touch of a Chenghua porcelain vessel is unmatched by porcelains of any other period.

What is generally known as 'palace bowls' are bowls of fine proportion, painted in underglaze blue with a flower or fruit design of apparent simplicity. Bowls with flower scroll decoration were of course also made in the Yongle (AD 1403 – 1424) and Xuande periods, but those of the Chenghua reign are unique in the deliberate irregularity introduced to a seemingly regular pattern. In the present design, blooms basically alternate with leaves, but further occasional leaves are appearing behind some of the blooms, a single bud is added on the outside, and the stems do not undulate in a predictable manner. Two slight variations of this pattern exist, where the stems on the inside are entwined in a different way. It is this slight deviation from the orderly arrangement, which makes this and other palace bowl designs vibrate, as if pervaded with some quiet motion, quite unlike earlier and later designs.

The musk mallow design with its softly rounded flower petals and serrated finger-like leaves is easy to identify through the classic botanical literature. It was used already on some rare Yongle vessels, such as a ewer in Topkapi Saray, Istanbul, and an identical one sold in these rooms, 30th October 2002, lot 271. The central rosette is also derived from flower-scroll bowls of the Xuande period.3 Wheras mostly, the rosette is six-petalled, the present one with its seven petals displays the same tendency towards asymmetry.

The present bowl is one of only two bowls of this design still remaining in private hands, while eleven examples are in museum collection, six of them in Asia and five in Europe; none are preserved in mainland China or in the United States. Beside this piece only three such bowls have ever been offered at auction, one for the last time in 1951, another in 1973 and the third in 1981. Examples of this design have been recovered among the fragments remaining from the waste heaps of the Ming Imperial kilns at Jingdezhen; one reconstructed example was included in the exhibition The Emperor's Broken China: Reconstructing Chenghua Porcelain, Sotheby's London, 1995, cat.no.69.

Companion pieces in Asia are four bowls preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, recorded in the museum's porcelain catalogue Gugong ciqi lu, part II: Ming, vol.1, Taipei, 1962, p.214, three of which have been published with illustrations, two in the Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Ch'eng-hua Porcelain Ware, 1465 – 1487, Taipei, 2003, cat.nos.33 and 34; the third in the exhibition catalogue Ming Chenghua ciqi tezhan [Special exhibition of Ming Chenghua porcelain], Taipei, 1976, no.80.

One bowl from the collections of Lindsay Hay and R.E.R. Luff, later in the Ataka collection and now in the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, sold in our London rooms in 1946 and 1973, was included in the Museum's exhibition Imperial Porcelain: Recent Discoveries of Jingdezhen Ware, Osaka, 1995, pl.229; another bowl from the collections of C.M. Woodbridge and Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Bernat, now in the Umezawa Kinenkan, Tokyo, sold in our London rooms in 1951, formed part of the Special Exhibition of Chinese Ceramics, Tokyo, 1994, pl.263. A bowl from the Cunliffe collection, still remaining in a private collection, sold in these rooms 20th May 1981, lot 689, and illustrated in Sotheby's: Thirty Years in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2003, no.248, was included in the Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Ceramics, Kau Chi Society of Chinese Art in association with the Art Gallery, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1981-2, catalogue p.73.

In Europe, there is a pair of bowls of this design from the collection of Axel and Nora Lundgren in the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm, see Jan Wirgin, Ming Porcelain in the Collection of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Hongwu to Chenghua, Stockholm, 1991, cat.no.35; one bowl in the Percival David Foundation, London, was included in the exhibition Flawless Porcelains: Imperial Ceramics from the Reign of the Chenghua Emperor, London, 1995, cat.no.1; another from collection of Mrs. Winnifred Roberts is in the British Museum, London, given in memory of A.D. Brankston, and published in Jessica Harrison-Hall, Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, no.6:4; and one in the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, in the Netherlands, is illustrated in Daisy Lion-Goldschmidt, Ming Porcelain, London, 1978, pl.66.

Chenghua porcelain remained greatly treasured throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties. Ts'ai Ho-pi relates many anecdotes recorded in the historical literature attesting to the value and esteem of Chenghua wares in later periods.4 The rulers most interested in the collecting ancient ceramics, the Wanli (r. AD 1573 – 1620) and Yongzheng (r. AD 1723 – 1735) Emperors both had copies commissioned from the Imperial kilns, the former with his own reign marks, the latter with a spurious Chenghua mark. A bowl of this design of Wanli mark and period in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, was included in the Museum's 1976 exhibition together with an original piece, op.cit., cat.no.79; a Qing copy in the Percival David Foundation, is illustrated in The World's Great Collections: Oriental Ceramics, vol.6, Tokyo, New York and San Francisco, 1982, no.252.

1 Liu Xinyuan 'Reconstructing Chenghua Porcelain from Historical Records', The Emperor's Broken China: Reconstructing Chenghua Porcelain, exhibition catalogue, Sotheby's London, 1995, p.11.

2 See Julian Thompson's 'List of Patterns of Chenghua Porcelain in Collections Worldwide', ibid., pp.116-129.

3 E.g. Mingdai Xuande guanyao jinghua tezhan tulu/Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Selected Hsüan-te Imperial Porcelains of the Ming Dynasty, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1998, no.61.

4 Ts'ai Ho-pi, 'Chenghua Porcelain in Historical Context', Sotheby's London, 1995 (op.cit.), pp.16ff.

Sotheby's. Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art. 08 Oct 09. Hong Kong www.sothebys.com

Another Palace Bowl, Chenghua mark and period was in Lord Cunliffe collection and sold at Bonhams on 11th november 2002. "The star lot of today's sale is a rare 15th century 'Palace Bowl' (pictured). The bowl, together with its pair (which was sold in 1980 for 200,000 pounds), cost Cunliffe 475 pounds in 1947. Measuring just five and three quarter inches in diameter, it is now estimated to fetch between 200,000 pounds and 300,000 pounds. Were it not for the loss of a tiny flake of glaze it would, says Bonhams' Asian art expert, Colin Sheaf, be worth 'over 1 million pounds.'

Another Palace Bowl, Chenghua mark and period was in Lord Cunliffe collection and sold at Bonhams on 11th november 2002. "The star lot of today's sale is a rare 15th century 'Palace Bowl' (pictured). The bowl, together with its pair (which was sold in 1980 for 200,000 pounds), cost Cunliffe 475 pounds in 1947. Measuring just five and three quarter inches in diameter, it is now estimated to fetch between 200,000 pounds and 300,000 pounds. Were it not for the loss of a tiny flake of glaze it would, says Bonhams' Asian art expert, Colin Sheaf, be worth 'over 1 million pounds.'

Made in the 1470's for the personal use of Emperor Cheng Hua, it is decorated with lilies painted in rich cobalt blue under a brilliantly clear glaze. The flawless potting, elegant form, and minimal decoration demonstrates how, under Cheng Hua, Imperial Chinese porcelain production reached an unsurpassed level of sophistication. Judging by the large number of rejects of this period that have been excavated from the site of the Imperial kiln in Jingdezhen in central South China, this was achieved regardless of cost.

The last Cheng Hua 'Palace Bowl' at auction was sold by Christie's in Hong Kong for 350,000 pounds in 1996. Bonhams has no branch in Hong Kong, but according to Sheaf, the most likely buyer for a secular work of this quality is one of the newly rich mainland Chinese, of which Forbes lists fifty as worth over 100 million pounds each, who are repatriating their heritage." Colin Gleadell www.telegraph.co.uk

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_2a8420_437713933-1652609748842371-16764302136.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_83ee65_2024-nyr-22642-0954-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_15808c_2024-nyr-22642-0953-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_e54295_2024-nyr-22642-0952-000-a-rare-blue-an.jpg)