Andy Warhol's Iconic 200 One Dollar Bills from 1962 Sells for $43,762,500 at Sotheby's

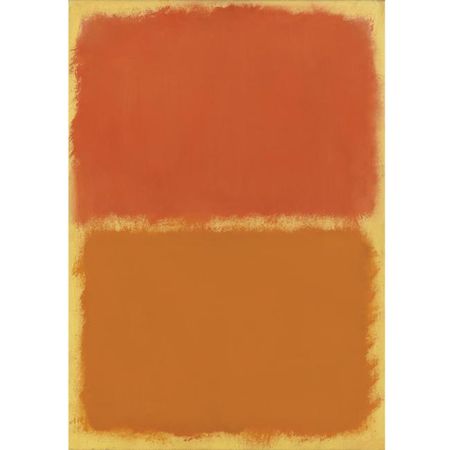

Mark Rothko (1903 - 1970), Orange, Red, Orange, Executed circa 1961 - 1962, oil on paper mounted on panel, 29 x 20 7/8 in. 73.7 x 53 cm. Est. 2,000,000—3,000,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 3,386,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

NEW YORK, NY.- Tonight at Sotheby’s in New York, Andy Warhol’s monumental masterpiece, 200 One Dollar Bills, brought a remarkable $43,762,500, soaring past the pre-sale estimate of $8/12 million. Competition was fierce. Auctioneer Tobias Meyer opened the bidding at $6 million and was immediately met with an almost unheard of response - a bid of $12 million, twice his opening bid. Five more bidders raised their paddles before the winning bid was cast by an anonymous purchaser bidding on the telephone. The Warhol was the top-selling lot in a sale of Contemporary Art that brought an outstanding total of $134,438,000, far-above pre-sale expectations (est. $67.9/97.7 million) and with all but two lots finding buyers. The sale was 98.6% sold by value and 96.3% sold by lot – the highest sold-by -lot total by lot in about twenty years, with only one exception. New auction records were established for Alice Neel, Jean Dubuffet, Juan Muñoz and Germaine Richier; as well as for a sculpture by Willem de Kooning, a neon by Bruce Nauman and a work on paper by Jackson Pollock.

“The desire for great art is very strong,” said Tobias Meyer, Worldwide Head of Contemporary Art. “In a market that has been characterized by pent-up demand, we were able to offer fresh material with conservative estimates, and our sellers were rewarded with the remarkable results we saw this evening.”

Anthony Grant, International Senior Specialist of Contemporary Art, noted, “The stars aligned tonight. With an offering of true icons of post war art, we saw bidding from all corners of the world, from both dyed-in-wool collectors and new clients alike. The Myers Collection in particular offered a great international sampling of artists – Richier, Gottlieb, Appel and Neel - and attracted a great depth of bidding, both private and institutional.”

“Andy Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills is a hugely important work for American art history,” said Alex Rotter, Head of the Contemporary Art Department in New York. “Not only was it one of the starting points of Pop Art, but this picture had the perfect ownership history – directly from Warhol’s dealer to the legendary collector Robert C. Scull, and then from his estate sale at Sotheby’s to the current owner who acquired it in 1986 for $385,000. We are immensely gratified by the extraordinary price of more than $43 million achieved for the work this evening.”

Andy Warhol (1928 - 1987), 200 One Dollar Bills, 1962. silkscreen ink and pencil on canvas, 80 1/4 x 92 1/4 in. Est: 8,000,000—12,000,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 43,762,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Green Gallery, New York

Robert C. and Ethel Scull, New York

Sotheby's, New York, Contemporary Art from the Estate of the late Robert C. Scull, November 11th, 1986, Lot 28

Acquired by the present owner from the above

EXHIBITED: New York, Green Gallery, 1962 (Group Show)

Philadelphia, Institute of Contemporary Art, Andy Warhol, October - November 1965, cat. no. 27, illustrated (detail)

Boston, Institute of Contemporary Art, Andy Warhol, October - November 1966, cat. no. 3, illustrated (titled Dollar Bills)

Philadelphia, Institute of Contemporary Art, Grids, January - March 1972, illustrated

Zurich, Kunsthaus, Andy Warhol: ein Buch zur Ausstellung 1978 im Kunsthaus Zürich, May - July 1978, cat. no. 109

Milwaukee, Milwaukee Art Center; Richmond, Virginia Museum of Arts; Louisville, J.B. Speed Museum; New Orleans, New Orleans Museum of Art, Emergence & Progression: Six Contemporary Artists, October 1979 - September 1980, p. 71, illustrated

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: Solomon Hudson, "Images of the Fine Arts", Penn Comment, vol. 2, no. 2, October 1965, p. 5, illustrated (detail)

Max Kozloff, "The Inert and the Frenetic", ArtForum, vol. 4, no. 7, March 1966, p. 44, illustrated

Christopher Finch, Pop Art: Object and Image, London, 1968, p. 151, illustrated (upside down)

Exh. Cat., Stockholm, Moderna Museet, Andy Warhol, 1968, n. p., illustrated on two consecutive pages

"A Creative Interest in Cash", Life, September 19, 1969, p. 52, illustrated

John Coplans, Andy Warhol, London, 1970, p. 38, illustrated

Rainer Crone, Andy Warhol, New York, 1970, cat. no. 547

Jean Lipman, "Money for Money's Sake," Art in America, vol. 58, no. 1, January - February 1970, p. 78, illustrated

Exh. Cat., London, Tate Gallery, Warhol, 1971, fig. 27, p. 45, illustrated

Rainer Crone and Wilfred Wiegand, Die Revolutionäre Ästhetik: Andy Warhol's, Darmstadt, 1972, p. 72, illustrated

Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, American Pop Art, 1974, fig. 95, illustrated

Rainer Crone, Das Bildnerische Werk Andy Warhols, Berlin, 1976, cat. no. 898

David Bourdon, Warhol, New York, 1989, pl. 103, p. 107, illustrated

Georg Frei and Neil Printz, The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculpture 1961-1963, vol. 1, Zurich and New York, 2002, cat. no. 125, p. 125, illustrated in color and fig. no. 113, p. 130, illustrated in color (at Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, 1965), fig. no. 116, p. 146, illustrated (with the artist in his studio, 1962) and fig. no. 121, p. 148, illustrated (at Green Gallery, New York in 1962)

NOTE: 200 One Dollar Bills is the monumental masterpiece from Warhol's first series of silkscreened paintings and is a powerful declaration of the genesis of Warhol's major contribution to art history. Warhol had already revolutionized American art by restoring representation and objective imagery to painting in the startling guise of common, everyday objects such as Campbell's Soup Cans, comics, magazine advertisements and newspaper headlines in late 1961 to early 1962. But the `Pop Art' revolution was not complete until Warhol discovered the artistic technique that would give him the freedom to exploit his new approach to subject matter. Warhol responded to the post-war world's media and consumerist saturation by seeking a form of art that would remove the hand of the artist, creating the same sense of distance and disconnect that was emerging in the world around him. Earlier Warhol had painted projected images and used stencils and rubber stamps, as formalist experiments, but silk-screening would prove to be his perfect muse. Screening was a mechanical process, and represented an intervention between the artist and the canvas; but in his usual contradictory manner, Warhol would subvert his own intention of ``mechanized art'' by using the process to create an unending variety of images of both beauty and emotional impact, as well as ground-breaking influence. The series of ``Dollar Bill'' paintings were done in March-April 1962 and Warhol's first silkscreens were created from ink drawings he made on acetate, picturing the fronts and backs of one- and two-dollar bills. Later that year, Warhol expanded his silkcreening experimentation with the photo-silkscreen process in paintings such as Baseball (August 1962, Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City).

The ``Dollar Bill'' series consist of predominantly small paintings of single dollar bills (some shown front and back), with only 10 paintings of dollar bills done in serial or group formats. 200 One Dollar Bills and 192 One Dollar Bills (collection of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie, Collection Marx, Berlin) are the two largest paintings, one a horizontal format and the other a vertical. The present work was screened over a soft gray ground that would become the base color most often used by Warhol at this early stage of his oeuvre, while 192 One Dollar Bills was screened on a light green acrylic ground. As counterpoint to the gray ground and black ink, Warhol screened the U. S. Treasury Seal in a deep blue, providing a counterpoint that brightly activates the overall composition. Warhol had fist used the structure of repeated imagery in 200 Campbell's Soup Cans (Powers Collection), 100 Cans (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo) and 100 Campbell's Soup Cans (Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt). But these paintings were created prior to his silkscreen technique and were more laborious, involving layers of stencils for the different colors and different parts of the soup can. Such an involved technique did not lend itself to the artist's wish to produce a large number of works using the same image - as he would ultimately do in his `Factory' and as he initially conceived with the multi-panel, individually framed 32 Campbell's Soup Cans (Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York) shown at Ferus Gallery. More importantly, Warhol's earlier methods did not lend themselves to his ulitmate goal; a repetitive multiplicity of one image within the same work. In discovering his silkscreen technique with the dollar bill image, Warhol created his first true serial masterpiece, in subject and technique, with 200 One Dollar Bills.

In one other important aspect, 200 One Dollar Bills is a quintessential painting of its time: its provenance is the storied collection of Robert and Ethel Scull. The Sculls' fortune derived from taxi cabs and they were New Yorkers to the core. They were also one of the earliest couples to collect and support the Pop Art movement, moving on from their earlier activities in collecting Abstract Expressionist art of the 1950s. They are still renowned as premier patrons of American Art in New York at that time and virtually became synonymous with Pop Art through their collection and their relationships with the artists. In addition to Warhol, their collection included masterworks by Jasper Johns, Bruce Nauman, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, George Segal and Mark di Suvero to name a few. The Sculls provided the financial backing for the seminal Green Gallery (1960-1966) in New York, directed by Richard Bellamy and 200 One Dollar Bills was one of two Warhol paintings purchased by the Sculls from the Green Gallery. The Sculls also owned other early works by Warhol: a 1962 Small Campbell's Soup Can (Tomato - Ferus Type), Big Torn Campbell's Soup Can (Pepper Pot) and 100 Cans (now in the Collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York). 200 One Dollar Bills was purchased by the present owner at Sotheby's from the sale of works from Robert Scull's estate in 1986, an event that was referenced in the artist's obituary the following year.

In addition to Warhol's 100 Cans, the quality of their collection has yielded a significant number of works now considered among the most important of the time and in major museum collections today, including one of Warhol's most important and earliest serial portraits. Ethel Scull 36 Times (Ethel Scull 35 Times) (June-July 1963) is the famous result of the artist's first session in a photo-booth with a subject, and this pivotal work is now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. James Rosenquist's monumental F-111 (1964-65) is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York and their Jasper Johns' 0 Through 9 (1961) set the auction record for a drawing by a Contemporary artist when it sold in November 2004 for $10.9 million. The cover lot for Sotheby Parke Bernet's sale of fifty works from the Scull collection in October 1973, Jasper Johns' famous ale cans titled Painted Bronze (1960), is in the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel.

The importance of 200 One Dollar Bills goes beyond the use of silkscreen and its history of ownership to another long-lasting cornerstone of Warhol's aesthetic practice: seriality.

As stated previously, the monumental ``Dollar Bill'' serial paintings are the second earliest serial paintings, executed after the large stenciled soup cans. The advantages of screen-printing are its quality as a form of pure reproduction, capable of multiple repetition, with great efficiency and neutrality. Warhol had now found the ideal medium to de-personalize the production of his art works, and at the same time, the method appealed to his visual sense. With the high contrast between `figure' and `ground', the association of ink with print media and the ability to endlessly repeat a single image, Warhol's art was forever changed. In the consumer world, his first large-scale serial painting of soup cans mimic the confounding sight of the packed display shelves in American stores that spoke of great prosperity and overabundance in post-war society. The ``Dollar Bill'' series was followed by works such as 210 Coca Cola Bottles (June-July 1962, Daros Collection, Switzerland), referencing an even more international symbol of American consumerism. Warhol could also now freely adopt a filmic presentation that mirrored the pervasive presence of electronic and printed imagery in the world of the 1960s: films, television and newspapers saturated modern life through repetition. The technique of photo-silkscreening that began with Baseball was put to its most poetic use in the Death and Disaster paintings of 1963 that capture the raw humanism of tragic events in the cool detachment of repetitive, mind-numbing ubiquity. Warhol's celebrity portraits, which mined the rich dichotomy between public and private persona, also reached their apogee in the great Marilyn diptychs such as Marilyn's Lips (August-September 1962, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.).

The subject matter of 200 Dollar Bills was even more suited to Warhol's themes of seriality, consumerism and universal imagery than his famous soup cans. As the ultimate symbol of desire and attainment, status and worth, need and greed, the dollar bill is without peer in its internationalism and potent symbolism. Like the S&H Green Stamps, actual money is printed on large sheets of paper, and thus begins its life as a serial image before it is distributed into the wider world. But more importantly, its primacy as international currency was in its ascendance and the post-war boom in America was a recognized phenomenon, as the dollar bill became a symbol of America in its essence just at the time Warhol captured it as art. By repeating the image on a canvas of such large proportions as 200 Dollar Bills, the impact in relation to human scale is overwhelming and the message is clear. The viewer's field of vision is filled with an expanse of dollar bills, as we lose ourselves in an enveloping, overall image, with as much revolutionary impact as Pollock's drip paintings of an earlier generation. But Warhol dismissed the need for self-referential and expressive gestures; his intent is to mirror our world back to us in a manner that highlights the impersonality, the ubiquity and the over-abundance of our material surroundings. There is more than one apocryphal story as to the original source for money as a subject for Warhol. In one story Eleanor Ward, the director of Warhol's first major gallery, the Stable Gallery, claimed that she promised Warhol his first one-man show in exchange for a painting of her lucky two dollar bill. In another version, an art and antiques dealer named Muriel Laptow suggested Warhol paint what he liked best, and his answer was ``money.'' The general basis for most of these stories is Warhol's concept of money as a commodity, and the artist famously spoke of how art could be interchangeable with money hanging on the wall. But in relation to 200 One Hundred Dollar Bills, his most pertinent sentiment is the role of this image in his adoption of the silkscreen. In 1977, the artist stated in an interview, ``I started [silkscreening] when I was printing money. I had to draw it, and it came out looking too much like a drawing, so I thought wouldn't it be a great idea to have it printed. Somebody said you could just put it on silkscreens.'' (Glenn O'Brien, ``Interview with Andy Warhol, High Times, no. 24, August 1977, p. 34).

The apparent simplicity and naiveté of Warhol's work and the initial criticism of it as too readily recognizable and too accessible to qualify as art has long been confounded. As one who appreciated irony, Warhol could enjoy the controversy of his ultimate recognition and success, as well as his deeply significant influence on younger artists that followed him in the 20th Century. As the decades pass, Warhol's place in the pantheon of American artists becomes ever more strongly established and the rare major works from the inception of his `Pop Art' aesthetics, such as 200 One Dollar Bills, are testaments to a pivotal moment in art history.

In addition to 200 One Dollar Bills several other works by Andy Warhol achieved strong prices tonight. A Self- Portrait from 1965 that the artist gave to Cathy Naso, a young receptionist at The Factory, sold for $6,130,500, more than tripling the pre-sale estimate of $1/1.5 million. More than seven bidders fought for the painting, which had been kept in a closest for 42 years, giving the colors a stunning quality and freshness.

“I think I am dreaming,” said Ms. Naso, who attended the auction this evening but chose to keep a low profile. “I’m simply overwhelmed, both by the amazing price and also by all the attention this painting received. After all these years in the closet, the painting has now come out and has travelled to London, to Hong Kong and has been seen all over the world. Andy has made me famous for fifteen minutes and I’ve come to realize that fifteen minutes of fame is more than enough.

Andy Warhol (1928 - 1987), Self-Portrait, signed, dated 1965 and inscribed to Cathy (2 years late) on the overlap, acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas, 22 1/2 x 22 1/2 in. 57.2 x 57.2 cm. Est. 1,000,000—1,500,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 6,130,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

This work has been authenticated and stamped by the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board and assigned the number A101.095 on the reverse.

PROVENANCE: Acquired by the present owner directly from the artist in 1967

NOTE: Self–portraiture, as an artistic genre, is a traditionally evocative subject for critical study and review. However, when examining the work of Andy Warhol, the theme is even more arcane as he was the master at blurring the line between public and private identity both in his art and his life. He created a world where soup cans were as significant as celebrities and media over-saturation could turn anyone or any object into a star. He used recycled images to corrupt the notion of artistic subject matter – including portraiture - and presented an image that no longer clearly identified the sitter in a straightforward way. Instead, his portraits demonstrate Warhol's attitude to the human contradiction of public persona versus private identity.

Warhol began to examine the effects and possibilities of self-portraiture when he was just 20 years old while studying at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh (Robert Rosenblum, Andy Warhol: Self- Portraits, St. Gallen, 2004, p. 21). During his time there, he composed a series of self-portrait drawings that depicted himself in the act of picking his nose. Though this is a universal act, it is typically considered offensive in public and has certainly never been seen before in self-portraiture. It is in this instance that Warhol first explored the marvelous dichotomy that is inherent in portraiture: one where he captured both truth and intimacy, while also being shocking and enigmatic. Robert Rosenblum once said, "From the beginning, Warhol offered a contradictory balance between up-close intimacy and calculated artifice" (Ibid, 21).

Self -Portrait demonstrates Warhol's deliberate statement of equating himself with stardom in the same fashion as his iconic portraits of Jacqueline Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, and Elizabeth Taylor. The first two series of Self-Portraits in 1963 and 1964 were in the same 20 x 16 inch format and were both based on photo-booth images, as used in other portraits at that time, such as the portrait of the New York collector Ethel Scull. With this 1966 series of Self-Portraits, which are acknowledged as the most well-known of his 1960s Self-Portraits, Warhol advanced several innovations. Similar to the 40 x 40 inch portraits of Jackie, Liz and Marilyn of 1964, Warhol now adopted a square format but in the more intimate scale of 22 by 22 inches. This resulted in the intentional cropping of his face, thus causing his head to "float" in a sea of bright shades and heavy shadowing. Most importantly, as with the 1962 Marilyn ``Flavors'', Warhol's self-portrait is an exercise in saturated, vibrant color. The photo-silkscreen was no longer based on a photo-booth strip and rendered a higher quality screen allowing for intense tonal contrasts. Largely abandoning the use of black silkscreen ink, Warhol now screened only in vivid hues of two, three or, as in this case, four bright colors. This deliberate use of shading and eccentric coloring is not atypical in art historical context: for instance, Pablo Picasso's Self – Portrait from 1901 encompasses similar dynamic color combinations and shadowing techniques forcing Picasso's face to glow, like that of Warhol's, in an eerie and hypnotic fashion.

The present work is an "uncanny combination of closeness and distance, of intimacy and indifference" (Ibid, 22). The image represents Warhol in a contemplative position; resting his head on his left hand, his fingers fan-like across his chin and mouth. The pose itself establishes a mysterious tone that brings the viewer into Warhol's psyche, while simultaneously rejecting any assumptions about him. Similarly, Jean Cocteau's self portrait drawing serves as an art historical foreshadowing to that of Warhol's. Cocteau depicted himself through merely an oval-shaped head and quizzical hand gesture, leaving the face completely void of any features. This suggests the curious dichotomy evident in self-portraiture, where the artist presented himself to the viewer for examination, while simultaneously insisting to remain elusive and impersonal. The proper right side of Warhol's face is cast in a shadow that prevents the viewer from looking him straight in the eyes. These visual elements combined with the hypnotic vibrancies of the color combinations create a dizzying perception of reality: one, which he reveled in.

For Warhol, this self-portrait epitomized him as an artist and individual; it is both startlingly personal and entirely detached, thus making it one of his most enigmatic and truly mesmerizing self-portraits. Untitled (Self-Portrait) is the paramount archetype of Warhol's self-portraiture. The silkscreen image possesses the ability to engage the viewer with this iconic Pop hero while simultaneously revealing very little about him, thus redefining the art of portraiture forever. Warhol once said, "If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There is nothing behind it" (Exh. Cat., Milan, Triennale di Milano, The Andy Warhol Show, 2004-5, p. 25).

An Untitled 1962 drawing of a roll of dollar bills, also by Warhol, that came from the collection of Leonard Newman, eventually sold for $4,226,500 against a pre sale estimate of $2.5/3.5 million with seven bidders competing.

Andy Warhol (1928 - 1987), Untitled (Roll of Dollar Bills), signed and dated 62 on the reverse, pencil, felt tip marker and graphite on paper, 39 7/8 x 30 in. 101.3 x 76.2 cm. Est. ,500,000—3,500,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 4,226,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Myron Orlofsky, New York

Acquired directly from the above

NOTE: Warhol revolutionized American art in the early 1960s, and 1962 was the most pivotal year in his entire oeuvre. Throughout that year, Warhol created a wide range of new stylistic aesthetics and art processes, culminating in his ground-breaking use of the silkscreen technique. Yet with works such as Untitled (Roll of Dollar Bills), also from 1962, Warhol proclaimed his continuing love of drawing.

Untitled (Roll of Dollar Bills) is a spectacular example of one of Warhol's earliest and most iconic drawings, similar to another work in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Throughout his life, Warhol expressed himself freely in drawing, and even after he became known for his silkscreen technique of mechanically producing paintings, Warhol would sneak into his 'Factory' studio to draw on Sunday or late at night when it was relatively empty. Warhol's innate talent for drawing is abundantly apparent in the present work, as well as his genius for infusing mundane subject matter with subtly deep meaning. As a subject, dollar bills would launch the artist into his famed silkscreen works later that same year. Fittingly, Warhol's dollar paintings and drawings are about desire, and it amused him that his art possessed powers similar to money, stimulating desire and imagination simultaneously.

As one of his early `Pop' works, Untitled (Roll of Dollar Bills) is a larger-than-life roll of money that directly confronts the viewer as it consumes the picture plane. Throughout his career, the dollar bill provided Warhol with a potent reference point for his examination of contemporary American consumer culture, acting as a recurring leitmotif with which to chart the changing times. As he explained, ``Americans are not so interested in selling. What they really like to do is buy''. (Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to Z and Back Again, New York, 1975, p. 229). In this context, Warhol's dollar paintings and drawings are as much about desire as his iconic celebrity portraits. Within a society immersed in the pursuit of wealth, Warhol's art would become a commodity acquisition that conferred status on its collector. As Warhol commented, "I like money on the wall. Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall." (Ibid., pp. 133-134).

In the present work, Warhol's ``still-life'' centered on a rather common roll of money, presenting a brand of 'Pop' culture reality that dared to challenge the grand history of `High art' still life painting as practiced by generations from Dutch masters and Caravaggio to 20th century masters such as Henri Matisse. Influenced by Marcel Duchamp, the champion of found objects in Modern art, Warhol's new `Pop' approach was parallel to the use of consumer objects in the works of contemporaries such as Jasper Johns, whose Light Bulb drawing from 1958 Warhol had acquired from Leo Castelli just one year before he completed Untitled (Roll of Dollar Bills). While each artist was striving toward different conceptual ends, their means had the same starting point in objects from everyday life.

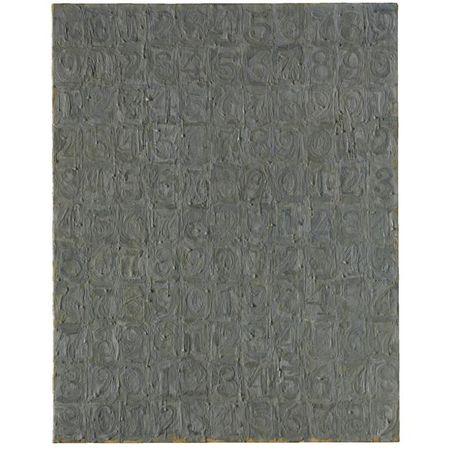

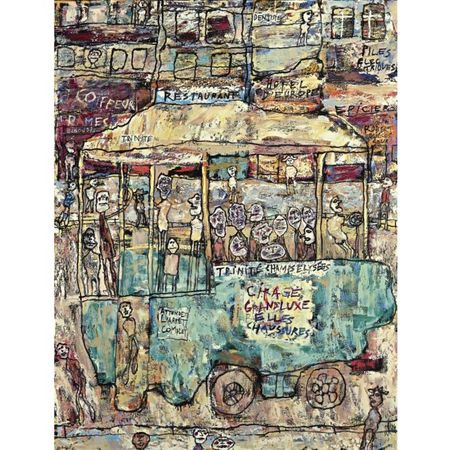

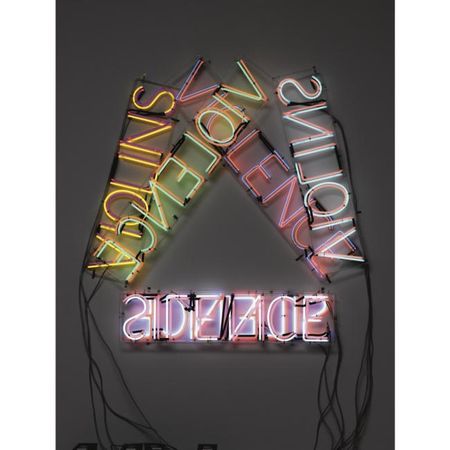

Other works that achieved strong prices include Jasper Johns’ Gray Numbers (lot 29), which saw seven bidders drive the price to $8,706,500 (est. $5/7 million). Orange, Red, Orange (lot 47) by Mark Rothko from the Estate of Lucia Moreira Salles had not appeared on the market for nearly 30 years and fetched $3,386,500 (est. $2/3 million) after a contest involving six bidders. Trinité-Champs Elysées (lot 48) by Jean Dubuffet made $6,130,500 (est. $4/6 million) and set a new record for the artist at auction. Violins Violence Silence (lot 27) by Bruce Nauman established a new record for a neon work by the artist when it sold for $4,002,500, comfortably in excess of the $2.5/3.5 million estimate.

Jasper Johns (B. 1930) Gray Numbers, signed and dated 1957 on the reverse, encaustic on canvas, 28 x 22 in. 71.1 x 55.8 cm. Est. 5,000,000—7,000,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 8,706,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

Jean Dubuffet (1901 - 1985) Trinité-Champs-Elysées, signed, titled and dated 61; signed, titled and dated mars 61 on the reverse, oil on canvas, 45¾ x 35 in. 116 x 89 cm. Est. 4,000,000—6,000,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 6,130,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

Bruce Nauman (B.1941), Violins Violence Silence, Executed in 1981-1982, neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, 62 1/8 x 65 3/8 x 6 in. 157.8 x 166.1 x 15.2 cm. Est. 2,500,000—3,500,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 4,002,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

The sale began with a group of 20 works from the Collection of Mary Schiller Myers and Louis S. Myers, noted collectors and arts benefactors from Akron, Ohio. Two world auction records were set by works from the Myers Collection: a record was set for American artist Alice Neel when six bidders competed for Jackie Curtis and Rita Red (Lot 2), which brought $1,650,500, well exceeding its estimate of $400/600,000, while Germaine Richier’s La Feuille (lot 4) was sought-after by six bidders, driving the price past the previous auction record and its estimate to bring $842,500. A new record for a Willem de Kooning sculpture was achieved by Large Torso, which sold for $5,682,500, well over the previous record of $3.9 million. Untitled XV, an abstract landscape from perhaps the most exuberant period in de Kooning’s rich and complex career, brought $6,130,500 against an estimate of $5/7 million. Donald Judd’s copper Untitled also exceeded expectations, bringing $1,650,500 against an estimate of $800,000/1.2 million.

Alice Neel (1900 - 1984), Jackie Curtis and Rita Red, signed and dated 70, oil on canvas, 60 x 41 3/4 in. 152.4 x 106 cm. Est. 400,000—500,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 1,650,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) today announced the acquisition of "Jackie Curtis and Rita Red" (Oil on canvas, 1970) by Alice Neel (American, 1900-1984). Purchased from the collection of Mary Schiller Myers and Louis S. Myers at Sotheby’s in New York on November 11, "Jackie Curtis and Rita Red" is widely recognized as a superb example of Neel’s work during the most fertile years of her career as well as one of her most moving pieces. CMA temporarily borrowed "Jackie Curtis and Rita Red" from the Myers for the inaugural opening of the East Wing this past summer in order to more fully represent the work of Neel and women artists of the 20th-century among the museum’s contemporary collection.

“I am sure many will be eager to see "Jackie Curtis and Rita Red" return to the newly opened East Wing galleries,” said Deborah Gribbon, interim director of CMA. “This purchase underscores the CMA’s focus on the continued development of our collection, always considered as one of the finest in this country, and specifically our dedication to acquiring the art of our time.”

Neel was a pioneering woman artist and one of the great portrait painters of the 20th-century. Neel’s work conveys a distinguished personal vision, which she forged in the crucible of the social experiences and cultural avant-garde of New York City. Throughout the years during which Modernism and art-for-art’s sake dominated debates about art, she championed an approach to painting that was rooted in human relationships. Neel’s work was fueled by her desire to draw attention to the lives of those whose contribution to society she viewed as unrecognized. Neel’s work has had a pervasive influence on artists of successive generations, including Chuck Close and Keith Mayerson.

This painting offers a significant parallel to the museum’s painting "Marilyn x 100" by Andy Warhol, resonates strongly with earlier figurative works and portraiture represented in the collection, and further strengthens the museum’s representation of work by women artists.

Germaine Richier (1902 - 1959) La feuille, bronze, height with artist's stone base: 58 1/8 in. 147.8 cm. Est. 250,000—350,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 842,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

Willem De Kooning (1904 - 1997) Large Torso, bronze, incised with the artist's signature and number 6/7 and stamped with the foundry mark Modern Art Foundry New York, 34 x 32 x 25 in. 86.4 x 81.3 x 63.5 cm. Est. ,000,000—6,000,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 5,682,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

Willem De Kooning (1904 - 1997) Untitled XV, 1977, signed on the reverse, oil on canvas, 59 x 55 in. 149.9 x 139.7 cm. Est. 5,000,000—7,000,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 6,130,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

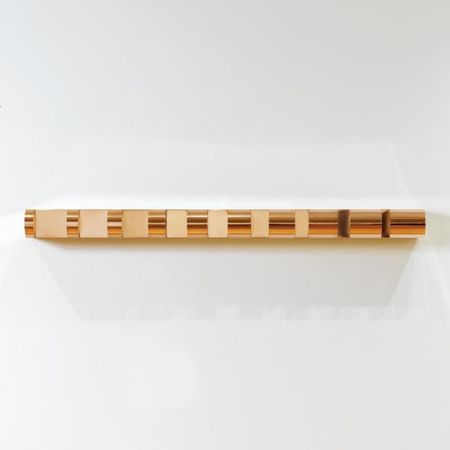

Donald Judd (1928 - 1994) Untitled, 1970, copper, 5 x 69 x 8 1/2 in. 12.7 x 175.3 x 21.6 cm. Est. 800,000—1,200,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 1,650,500 USD. Photo: Sotheby's.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F94%2F96%2F119589%2F128654286_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F11%2F119589%2F125968385_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F82%2F119589%2F122386859_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F14%2F119589%2F122123540_o.jpg)