Exceptional Works by Klimt, Giacometti, Cézanne, Matisse and Magritte at Sotheby's

Paul Cézanne (1830-1906), Pichet et fruits sur une table. oil on paper laid down on panel, 41.5 by 72.3 cm. 16 3/8 by 28 1/2 in. Painted in 1893-94. Estimate 10,000,000 - 15,000,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

LONDON.- Sotheby’s Evening Sale of Impressionist & Modern Art on Wednesday, February 3, 2010 will be the first ever London sale of its kind to include three works individually estimated to realise more than £10 million. The works - each one a masterpiece - are by Klimt, Giacometti and Cézanne. They form the nucleus of an exceptionally rich and varied sale which also offers major works by artists such as Matisse, Feininger, Schiele, Magritte, Miró and Moore.

Melanie Clore, Co-Chairman of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Department Worldwide, commented: “Following on from the success of our sales in New York in November, we are now delighted to present such important and rare works to the market, which not only reflect the confidence of our consignors, but also cater to the strong interest from collectors around the world for top quality works.”

The important still-life Pichet et fruits sur une table, painted in 1893-94 by Paul Cézanne, is estimated at £10-15 million. One of the finest works by the artist ever to come to auction, the painting dates from the period when Cézanne’s mastery of the still-life was at its height. The artist’s still lifes have long been recognised as being among his greatest achievements and they played a key role in the development of early 20th-century art. Commenting on Cézanne’s still-lifes, Roger Fry wrote: ‘It is hard to exaggerate their importance in the expression of Cézanne’s genius … because it is in them that he appears to have established his ideas of design and his theories of form.’ This painting was selected for the cover of the authoritative book Paul Cézanne, A Biography by John Rewald, the author of the Cézanne Catalogue Raisonné.

The quality of this still-life has been recognised by a series of illustrious collectors including Dr Albert C. Barnes, who acquired the work in 1920. His world famous Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania is home to many of Cézanne’s most celebrated works. The painting relates closely to Cézanne’s still-life of the same date formerly in the collection of Mr and Mrs John Hay Whitney, which was sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 1999 for $60 million. The distinctive blue patterned curtain and still-life composition with fruit also appear in three major oils now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C and the J. Paul Getty Museum in California.

Cézanne's life-long fascination with the genre of still-life reached its pinnacle in a group of paintings executed in the 1890s, of which Pichet et fruits sur une table is a supreme example.

More clearly, perhaps, than in any other subject, it is possible to trace the development of Cézanne's style in his still-lifes, since he could create and control the composition in the studio environment, arranging the elements in ways that provided an infinite variety of formal variations to be explored in the painting. The still-lifes of the early 1880s were mostly solid and compact, the spatial relationships of the depicted objects conveyed in a dense network of thickly-painted 'constructive strokes', but by the latter part of the decade and the early 1890s the artist began to abandon strict frontality in favour of more complex spatial arrangements, resulting in more dramatic compositions such as the present work.

Both the earthenware pitcher, which dominates in the present composition, and the patterned blue cloth to the left, appear in a number of Cézanne's still-lifes of this period. In each work, however, Cézanne viewed the materials at his disposal as if for the first time, arranging them in unexpected ways, changing proportions and establishing formal and spatial relationships that resulted in paintings of unprecedented variety and interest. The present work is most closely related to Rideau, cruchon et compotier, a painting of the same date, formerly in the Collection of Mr & Mrs John Hay Whitney, New York. The main difference between the two compositions is the exclusion of the white cloth in the present work. Instead, the objects are arranged directly on the wooden table-top, the rounded forms of the fruit, plate and jug creating a dynamic contrast against the flatness of the table, its angular shape and straight lines.

Writing about the Whitney picture, Isabelle Cahn observed: 'Here, the painter has placed a white faience compotier, a gray-blue glazed stoneware jug, and a carefully arranged white tablecloth on a simple wooden table that anchors the composition. On the left appears a blue drapery that is also found in several still lifes. Vollard recognized it (or perhaps another material familiar to him from the artist's work) in the Aix studio: "Close to the window hung a curtain that had always served as a background for portraits and still lifes." Fruit of various kinds – lemons, apples, pears, oranges – has been heaped in a pyramid in a compotier, nestled into the folds of the tablecloth, or placed directly on the wooden table, the vibrant colors contrasting starkly with the muted palette of the rest of the painting. [...] Volumes are described by directional brushstrokes that leave a discernible weave on the surface. The uniform back wall is also rendered in a multitude of blended brownish red, brownish green, and violet strokes. This patient evocation of modelling by means of color enabled Cézanne to imbue the motif with luminosity in the absence of artificial illumination. No shadows are cast on the wall, and each object radiates an individual clarity' (I. Cahn, in Cézanne (exhibition catalogue), op. cit., 1995-96, pp. 383-384).

The present work, Pichet et fruits sur une table, differs markedly from the other compositions centred on the earthenware jug, both in format and in the character of the paint surface itself. One of the most lyrical of the great still-lifes of the early 1890s, the relatively elongated format of the painting allowed Cézanne to space out the jug, plate and fruit horizontally. The blue patterned drapery, rather than establishing a forceful rhythm for the entire composition as it does in Nature morte aux aubergines of 1893-94 and La Bouteille de menthe of 1893-95 draws attention to the left portion of the canvas. It seems to weigh down the left edge of the table, warping it and distorting the perspective. Rather than suggesting the confines of a room, the subtly modulated background which ranges in hue from soft pinks and mauves to cooler blues and greens, opens up the space, so much so that the dish of fruit appears weightless behind the jug. Cézanne's still-lifes have long been recognised as being among his greatest achievements, the works which demonstrate most clearly the innovations that led to the stylistic developments of early twentieth-century modern art. Both art historians and artists have argued that Cézanne reached the very pinnacle of his genius within the discipline of the still-life, as this genre – unlike portrait or plein air painting – allowed him the greatest time in which to capture his subject. The young painter Louis le Bail described how Cézanne composed a still-life, reflecting the great care and deliberation with which he approached the process: 'Cézanne arranged the fruits, contrasting the tones one against the other, making the complementaries vibrate, balancing the fruits as he wanted them to be, using coins of one or two sous for the purpose. He brought to this task the greatest care and many precautions; one guessed it was a feast for him. When he finished, Cézanne explained to his young colleague, "The main thing is the modeling; one should not even say modeling, but modulating"' (quoted in J. Rewald, op. cit., 1986, p. 228).

The present work has a remarkable provenance. During Cézanne's lifetime, it was acquired by the prominent Dutch collector Cornelis Hoogendijk (1867-1911), who gathered a large number of Old Masters and modern works, and assembled one of the most important collections in the Netherlands and beyond at the turn of the twentieth century. In a buying frenzy that lasted between 1897 and 1899, he acquired over thirty paintings and watercolours by Cézanne from Ambroise Vollard. Some years after Hoogendijk'sdeath, the Paris dealer Paul Rosenberg acquired a number of Cézanne works from his estate, and sold them almost immediately to museums and French collectors. Thirteen works by Cézanne, including Pichet et fruits sur une table, as well as the painting from the John Hay Whitney Collection (fig. 1), were sold to the famous Pennsylvania collector Dr Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951).

As John Rewald wrote about this group of works: 'The list of the thirteen pictures shipped to Philadelphia is quite impressive [...] It was an extraordinary group, the single particularity of which was that it comprised only still lifes and landscapes, to the exclusion of any figure pieces, whether portraits, bathers, peasants, or mythological scenes. [...] But within these limits, Barnes now saw his collection overtaking numerically the group of Cézannes owned by Mrs. Havemeyer and, above all, he came into possession of some of Cézanne's finest works. [...] Among the still lifes there was not only a tremendous variety of compositions and objects, from fruits to jugs, from flowers to a skull, from ample folds of colorful drapes to bare table tops, there was also richness of texture, of vibrant brushwork, of smooth delicate strokes. It was a review of some of the artist's greatest achievements, represented by a number of works each revealing a different aspect of his genius' (J. Rewald, op. cit., 1989, pp. 271-272).

Gustav Klimt (1862 - 1918) Kirche in Cassone (Landschaft mit Zypressen) (Church in Cassone - Landscape with Cypresses), signed Gustav Klimt (lower left) oil on canvas, 110 by 110cm. 43 1/4 by 43 1/4 in. Painted in 1913. Estimate 12,000,000 - 18,000,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

Of equal rarity is Gustav Klimt’s Kirche in Cassone (Landschaft mit Zypressen) (Church in Cassone - Landscape with Cypresses), one of the most important landscapes by the artist ever to have appeared on the market. Estimated at £12-18 million, this beautiful, jewellike work was once part of one of the greatest early collections of Klimt’s work: that of the Austro-Hungarian iron magnate and collector Viktor Zuckerkandl (1851-1927) and his wife Paula. The painting went missing in Vienna during the Nazi period and only resurfaced several decades later. It is now being offered for sale pursuant to an agreement between the now 81-year old great nephew of the original owner and the European private collector in whose family the painting has been for several years.

Estimated at £12–18 million ($19-29 million/ €13.5-20 million), the painting will be the centerpiece of Sotheby’s forthcoming Evening Sale of Impressionist and Modern Art in London.

Commenting on the painting, Helena Newman, Vice-Chairman, Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Art department worldwide, said: “We are delighted to offer at auction Kirche in Cassone, one of the finest examples of Klimt’s landscape painting. The artist’s great achievement here was to combine the beauty and picturesque quality of the townscape with a highly personal, innovative technique. The dramatic perspective and the jewel-like, shimmering effect of his brushwork make this a composition of timeless beauty, a true masterpiece of Klimt’s art.”

The painting dates from a trip that the artist made to Lake Garda in the summer of 1913 with his muse and lover Emilie Flöge – a charismatic fashion designer and trend-setter with whom Klimt enjoyed “one of the most famous romantic partnerships of turn of the century Vienna” (Gustav Klimt & Emilie Flöge: Artist & Muse, Property from the Estate of Emilie Flöge, Sotheby’s 6 October 1999). Flöge was a profound influence on Klimt, inspiring some of his greatest paintings.

The importance of this particular work was not lost on the painting’s first owners, Viktor and Paula Zuckerkandl. They and their family were at the heart of Viennese social and cultural life, counting among their friends people such as the playwright Arthur Schnitzler, the composers Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoënberg, and collectors such as Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer and August and Serena Lederer. The Zuckerkandls were also among the greatest patrons of the arts in turn of the century Vienna: Viktor and Paula were early collectors of Klimt’s work, acquiring several extremely important pictures, including this, directly from the artist. They were patrons, too, of the Secessionist architect Josef Hoffmann, whom they commissioned to design the Wiener Werkstatt architectural masterpiece, the Sanatorium Purkersdorf, which Viktor founded and ran on the outskirts of Vienna. An exclusive spa, the sanatorium was a meeting place for the social, cultural and artistic elite. Completed in 1905, it was a Gesamtkunstwerk entirely furnished by the Wiener Werkstatt group, of which Klimt was a founding father.

When the Zuckerkandls died childless in 1927, part of their extraordinary collection was sold and the remainder passed into his remarkable family. Kirche in Cassone entered the collection of Viktor’s sister Amalie Redlich, who, together with her daughter Mathilde, was deported to Lodz in 1941 and never heard of again. After the Anschluss in 1938 she had made arrangements for her paintings to be stored by a shipping company. She paid the company’s foreman a hefty bribe of 2,000 Reichsmarks to ensure the safe-keeping of the crates, but although that may have prevented her property from being seized by the Gestapo, the paintings had nonetheless disappeared from the crates by 1947 when Redlich’s son-in-law returned and found the crates empty at the shipper’s premises. Only much later did Kirche in Cassone resurface in a private collection. Though the picture was acquired by the family of the present owner in good faith and with legal title, they have voluntarily agreed with the Zuckerkandl heir to offer this magnificent painting at auction.

The Artist and the Painting

Gustav Klimt (1862-1819) was the presiding influence on the artists and designers in turn of the century Vienna. He was the leading figure of the Wiener Werkstatt movement and the first president of the Sezession, which he founded in 1897.

Kirche in Cassone belongs to a celebrated series of lake paintings that rank among Klimt’s most important works. In these compositions, Klimt uses the reflections in the water to explore the picture plane in an innovative way. Here Klimt builds up his vision of the town through a mosaic of bright colours, with the houses rising vertiginously above the water. The flattening of the picture surface and the use of overlapping geometric forms undoubtedly show Klimt’s response to Cubism, which he had experienced during his trip to Paris in 1909, and later discussed with the younger avant-garde artist Egon Schiele (1890-1918).

In parallel with what Claude Monet was doing at the same time, Klimt started using square canvases which, together with the abandoning of traditional conventions of horizon and composition took landscape painting in a new and exciting direction. In contrast to his more meticulously planned figure compositions for which he generally executed large groups of pencil studies, there are scarcely any preparatory studies for the landscapes. As such, they bear witness to Klimt’s most direct response to the natural world, seen through the prism of his own unique vision.

Another outstanding work in the sale is L’Homme qui marche I, by Alberto Giacometti. One of the most important sculptures by the artist ever to have come to the auction market, this life-size work ranks among the most arresting and iconic of the artist’s bronzes. Its appearance at auction in February will mark the first time a Giacometti figure of a walking man in this monumental size has come to auction in over 20 years. More than that, this particular piece has the distinction of being a life-time cast. No life-time cast of the subject has ever been offered at auction before.

Formerly part of the corporate collection of Dresdner Bank AG (by whom it was acquired circa 1980), the work came into the possession of Commerzbank AG after the latter’s takeover of Dresdner Bank in 2009. Cast in 1961, L’Homme qui marche I is estimated at £12-18 million. Proceeds from the sale will be entirely put towards supporting Commerzbank’s foundations as well as selected museums.

Fauve and Expressionist works:

The market for Fauve and Expressionist works has grown apace in recent years. Helena Newman, Director of the Evening Sale and Vice Chairman of the Impressionist & Modern Art department, Sotheby’s Worldwide, remarks: “In recent years, we have seen an increasing number of buyers, particularly new buyers, looking for early modern masterpieces especially by Fauve and Expressionist artists such as Van Dongen, Kirchner and Matisse.”

Henri Matisse’s Femme couchée, estimated at £3.5-5.5 million, is a magnificent example of the artist’s favourite subject - that of a reclining woman in an interior - and this theme relates closely to his celebrated Odalisques series from the 1920s, which would become one of the most fascinating series of Matisse’s entire oeuvre. Probably painted in the artist’s studio on the Quai Saint-Michel in Paris around 1917, Femme couchée reflects the artist’s romantic and opulent approach that reached a culmination during his time in Nice.

Lorette, the semi-nude Italian model depicted, began posing for Matisse in 1915 and she is captured in the painting wrapped in a Spanish-style shawl and in a state of dreamy abandon on a vividly coloured and patterned sofa, which became a Matisse trademark. The model is said to have had a profound influence in liberating Matisse and his work.

The sale also includes works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Lyonel Feininger. Estimated at £1-1.5 million, Kirchner’s Variétéparade (Variety Show), a monumental portrayal of acrobatic stage performers, is an example of German Expressionist painting at its most exuberant. Commenced in 1910 in Dresden and finished in Switzerland in 1926, this remarkable work – full of joie de vivre – plays out all the aesthetic concerns that were at the heart of Die Brücke – the important avant-garde artistic collective of which Kirchner was a founding member.

Locomotive, a vividly coloured work by Lyonel Feininger, carries an estimate of £1.5-2.5 million. Having spent 15 years working as a successful illustrator for periodicals in Berlin and Paris, Feininger only turned his attention to oils later in life and Locomotive, painted in Paris in 1908, is a rare early work from the formative years of his career as a painter. The artist was fascinated by Paris city life and signs of modernity and the subject of trains and locomotives, in particular, was one that he returned to on numerous occasions in his graphic works, oils and drawings. Locomotive belonged to Feininger’s eldest son Andreas from his time as a young boy and the painting remained in the artist’s family for almost a century.

Gustav Klimt was a great friend and mentor to his younger compatriot Egon Schiele, who is represented in February’s sale by Sitzende Frau mit violetten Strümpfen – one of the most arresting and accomplished works on paper from Schiele’s mature period. Although not depicted in the nude, the female subject radiates a palpable erotic appeal. She takes up the entirety of the picture surface, her physical presence so dominant that her head appears to extend beyond the edge of the sheet. The sitter is most likely to be Adele Harms, whose sister Edith Schiele married and for whom he evidently harboured a strong physical desire. Executed in 1917, just a year before his untimely death, the work dates from a period of relative success and prosperity for Schiele. As Jane Kallir observed: “His line, by 1917, had acquired an unprecedented degree of precision... Schiele’s hand had never been surer, more capable of grasping, in a single breathtaking sweep, the complete contour of a figure.... he had found, in the best of his late work, the perfect line.” Amply demonstrating this, Sitzende Frau mit violetten Strümpfen is estimated at £3-5 million.

René Magritte (1898 - 1967), Le Beau Navire, signed Magritte (lower left); titled on the reverse, oil on canvas, 93 by 70.5cm. 36 5/8 by 27 3/4 in. Painted in 1942. Estimate 2,500,000 - 3,500,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

Surrealist works:

February’s sale will also include a strong section of Surrealist works and the group is highlighted by Le Beau Navire, a mysterious composition by René Magritte in which a serene, almost sculpture-like female nude is set against a dramatic seascape. Estimated at £2.5-3.5 million, the painting belongs to a group of works that Magritte executed in the 1940s, all depicting classical female nudes in unidentified landscapes, the woman’s upper body permeated by the tone of the sky behind in what has been described as a pictorial reference to black magic: “It is an act of black magic to turn woman’s flesh into sky.” (David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield, René Magritte, Catalogue Raisonné.)

Le Beau navire belongs to a group of works Magritte executed in the 1940s, depicting a female nude in an unidentified landscape. The woman is painted in a classical manner, abiding by the laws of beauty and proportion, resembling a marble sculpture or a mythical figure as much as a live model. This traditional representation, however, is juxtaposed with the unexpected colouration of the figure, whose upper body gradually acquires the tone of the sky behind her. In nearly all paintings from this group, the woman has one hand resting on a block of stone. As Magritte himself proclaimed: 'One idea is that stone is associated with an 'attachment' to the earth. It does not rise up of its own accord; you can rely on its remaining faithful to the earth's attraction Woman, too, if you like. From another point of view the hard existence of stone [...] and the mental and physical system of a human being are not unconnected' (quoted in Jacques Meuris, René Magritte, London, 1988, p. 76). The nude is always beautifully painted, her body conforming to the classical ideals of proportion.

Depicted either with her eyes closed, or with her head turned away from the viewer or, as in the present work, with blank eyes resembling those of a classical sculpture, the nude becomes the passive object of the spectator's gaze and erotic desire. 'Magritte said, in fact, that an undercurrent of eroticism was one of the reasons a painting might have for existing. It asserted itself most intensely and explicitly in these stately classical nudes with their cool coloring. For the very reason that it aims at maximum resemblance, their academicism is upset by the provocation of mystery emanating from that identification, once the painting and the arrangement of the painting interfere with its course. The prime example is [La Magie noire; fig. 1]' (ibid., p. 76).

The subject of this work became one of Magritte's favourite images in the 1940s, and he used it in several oils, with variations on the position of the nude, which is variably depicted frontally and in profile, sometimes she has a dove resting on her shoulder, and other times, as in the present work, she holds a rose in her hand. While Magritte gave these pictures various titles, the one most often used is La Magie noire. The title of the present work, however, was inspired by a poem by Charles Baudelaire and, as was often the case, was chosen by Magritte's friend and fellow Surrealist Marcel Mariën. Writing about Magritte's first painting on the theme of La Magie noire, executed in 1934 (D. Sylvester, op. cit., no. 355), David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield wrote: 'Those pretty colours serve an image-making as well as a decorative purpose: the top half of the nude is painted a gradated blue, near enough that of the sky behind; from the waist down, the colour is a flesh tone. It is a process of metamorphosis. 'Black magic. It is an act of black magic to turn woman's flesh into sky' (ibid., p. 187). In some compositions the nude is placed in an environment which is at the same time an interior and exterior. Later in the decade, Magritte transformed this image by replacing the standing nude with a three-part torso, thus further reducing the image of a woman to a man-made object, evoking a sculpture despite her naturalistic flesh tone. The landscape in which the nude is depicted also varies between different versions of the painting. In the majority of the compositions, Magritte depicted a universal, non-descript image of a blue sky and a calm sea. In the present work, however, the background consists of a more dramatic sea-scape, with foamy waves rolling towards the figure. This image of the waves, which Magritte used in several other major works, was inspired by La Vague, a painting by a little known Armenian artist Wartan Mahokian, of which Magritte owned a post-card, squared-up by his hand in order to be transferred onto his canvases (fig. 4). With a remarkable economy of means, Magritte has transformed the traditional subject of a nude in a landscape into a mysterious composition, and it is this Surrealist sense of displacement that makes Le Beau navire a masterpiece of his art.

Joan Miró (1893 - 1983), Peinture (Le Pêcheur), signed Miró and dated 1927 (lower right); signed Joan Miró and dated 1927 on the reverse, oil on canvas, 16.7 by 22.4cm. 6 5/8 by 8 3/4 in. Painted in 1927. Estimate 300,000 - 400,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

Another work in the sale is Peinture (Le Pêcheur) by Joan Miró, a quintessential Surrealist composition painted in 1927 at the height of the artist’s involvement with the Surrealist group (est: £300,000-400,000).

Painted at the height of his involvement with the Surrealist group, Miró's Peinture (Le Pêcheur) of 1927 brilliantly exemplifies the artist's move towards his supremely abstract canvases. Unlike Dalí's and Magritte's figurative version of Surrealism, Miró's artistic development took a different turn. He joined the group in 1924, and participated in their first exhibition held at the Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925. André Breton commented that Miró 'may be looked upon as the most Surrealist among us' (A. Breton, Le Surréalisme et la peinture, quoted in Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró: Life and Work, London, 1962, p. 156). Breton's first Surrealist manifesto of 1924 proclaimed: 'in the future resolution of the two states, seemingly so contradictory, which are dream and reality, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality'. This new ideology encouraged Miró to eliminate representation from his canvases. Coinciding with his own pictorial experiments, it encouraged him to abandon realism in favour of the imaginary.

In the present work, he used whimsical and ambiguous forms that first appear abstract, only to take form gradually in shifting and delightful ways. The central figure of a fisherman, holding a fishing rod, is executed in a freely meandering line, its hollow, translucent shape set against a monochrome blue background. In its powerful simplicity, Peinture (Le Pêcheur) reveals a mastery of the void, exploring a very new sense of space. Verging between figuration and abstraction, Miró's whimsical forms originate from the world of dreams and the unconscious, their otherworldly character emphasised by the void of the background that the images populate.

Jacques Dupin commented about this fantastic quality of Miró's works from this period: 'What Miró did achieve was the arduous conquest of powers lost since childhood. And he succeeded by going his own way, stubbornly, passionately, with consciousfidelity to his own gifts and to the conditions of painting. It was from the inside, by pushing painting to its extreme consequences, that he made it possible to go beyond paintings, to reach the domain that lies beyond it' (ibid., p.156).

This will be offered alongside further notable works by Francis Picabia (La Transparence, est: £500,000-700,000), Max Ernst (Arbre et deux personnages, est: £400,000-600,000), and Jean Arp (Tête Bouteille, est: £200,000-300,000).

Sculpture:

Like Fauve and Expressionist art, Modern sculpture has also seen a remarkable growth of interest in recent years and it is well represented in the sale. Monumental sculpture, in particular, has been separately showcased at Sotheby’s annual selling exhibitions of modern and contemporary sculpture held at Chatsworth, where an increase in interest from international collectors has been evident.

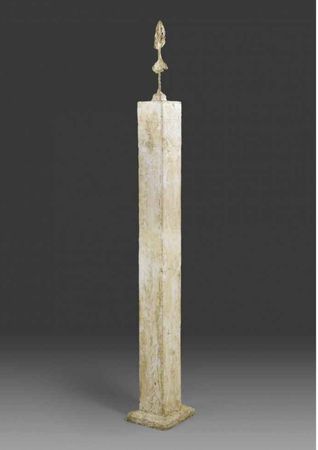

Alberto Giacometti (1901 - 1966), Petit Buste sur Colonne, painted plaster, height: 153.5cm. 60 1/2 in. Executed circa 1952, this work is unique. Estimate 1,800,000 - 2,500,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

Alongside the life-size Giacometti bronze mentioned above, the sale will also include a rare example of a unique painted plaster by the artist. Estimated at £1,800,000-2,500,000, Petit Buste sur Colonne was given by the artist to the current owner in 1952 and appears now for the first time ever on the market, having been in the same collection for over half a century.

'...in reality we always see in colour, don't we? If I make a sculpture in grey clay or cast in bronze, the impression of thinness is greater; if I paint it it tends to look much more true than if it's not painted. That's why I always feel I wanted to make painted sculpture' Alberto Giacometti

Throughout his career, Giacometti occasionally painted his sculptures, in order to enhance their individuality and expressiveness. In his early period, the artist had painted some of his plasters, and from the 1950s started applying paint to bronzes as well. As he portrayed his brother Diego in numerous paintings and sculptures, the present work is a fascinating composite of these two mediums, bringing together the rich treatment of the plaster surface and the liveliness of oil paint.

As Giacometti once said, 'There is no difference between painting and sculpture.' Since 1945, he added, 'I have been practicing them both indifferently, each helping me to do the other. In fact, both of them are drawing, and drawing has helped me to see' (quoted in Yves Bonnefoy, Alberto Giacometti, A Biography of His Work, Paris, 1991, p. 436).

In an interview with David Sylvester, Giacometti discussed his painted sculptures: 'Not long after I'd begun to do sculpture I did paint a few, but then I destroyed them all. I repeated this at times. In 1950 I painted a whole series of sculptures. But as you paint them you see what's wrong with the form. And there's no point in painting something you don't believe in. [...] I can't waste time fooling myself that I've achieved something by painting it if there's nothing underneath. So I have to sacrifice the painting and try and do the form. In the same way as I have to sacrifice the whole figure to try and do the head' (quoted in D. Sylvester, Looking at Giacometti, London, 1994, p.218).

In the 1950s, Giacometti executed several sculptures depicting the bust of his brother Diego on a tall, slender pedestal. Throughout his life, Giacometti was fascinated by the theme of the human condition, and the fragility and remoteness of these works emphasise his existentialist concerns.

'To the slender and fragile figures he stands on bases or on pillars which, by contrast, are mposing, Giacometti gives a double metaphysical value of our mortal condition. Here, the pillar isn't used to make the place above sculpture more monumental, but it is to stress its frailty and to suggest the enormous space surrounding it' (Giacometti (exhibition catalogue), Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, 1991-92, p. 308).

Petit buste sur colonne has been in the collection of Yvon Taillandier from the time it was made until now. A talented artist, journalist, novelist and art critic, Taillandier met Alberto Giacometti for the first time in 1952. Recalling their first encounter outside the Galerie Louise Leiris, Taillandier noted that 'Giacometti did not look like a Giacometti then... I remember saying to myself that he had the head of a Roman emperor, not realizing that I was comparing him with a kind of sculpture he didn't like... Probably because I am superstitious, I upgraded him to the status of deity'.

Taillandier's interview with Giacometti was first published in the Swedish art journal Konstrevy in 1952, and later in book form under the title Je ne sais ce que je vois qu'en travaillant, published in France in 1993.

In this short interview Giacometti made perceptive and articulate observations on art history and his attitude to his own work. Discussing his sculptures he explained to Taillandier: 'In short, if I compare modern sculptures (those that are abstract, or tending towards the abstract) to prehistoric objects, it seems to me that they are not "descended" from the first sculpture to represent a woman, but rather from prehistoric axes. And, in this way, they pass from one domain to another, and become objects. Now, in my view, an object ceases to be a sculpture. For me, a sculpture must be the representation of something other than itself. A sculpture only truly interests me to the extent that it is, for me, the means of rendering the vision that I have of the external world ... Or, further still, a sculpture is for me today merely the means of discerning this vision. To such a point that it is only through working that I know what I can see' (A. Giacometti, Je ne sais ce que fje vois qu'en travaillant, propos recueillis par Yvon Taillandier, Paris, 1952). Taillandier received the present work as a gift from the artist in 1952 after it was exhibited at the Salon de Mai, and it has remained treasured in his collection for jthe last 58 years.

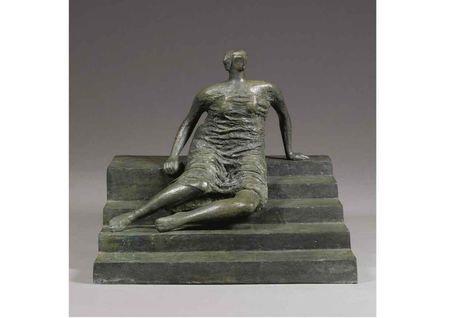

Giacometti’s masterful paring down of the sculpted form can be viewed in the sale alongside a very different treatment of the human figure: that of the legendary British sculptor Henry Moore. Moore is represented in the sale by two works. A monumental outdoor bronze Reclining Figure is estimated at £2,500,000 £3,500,000 and this impressive piece explores the subject that was one of Moore’s chief preoccupations during his long career. It was bought directly from the artist’s studio by the present owner and has remained in the same collection for over 25 years. It will be complemented by a more intimate piece: Working Model for a Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps, which belongs to a series of seated figures that Moore created while developing ideas for the sculpture he was commissioned to make for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and is estimated at £500,000-700,000.

Henry Moore (1898 - 1986), Reclining Figure, inscribed Moore, numbered 7/9 and inscribed Morris Singer Founders London, bronze, length: 246cm. 96 7/8 in. Executed in 1982 and cast in bronze in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist's proof. Estimate 2,500,000 - 3,500,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

The subject of the reclining figure, initially inspired by Mexican sculpture and explored in this monumental work, was one of Moore's chief preoccupations throughout his long career. He has commented that 'from the very beginning the reclining figure has been my main theme. The first one I made was around 1924, and probably more than half of my sculptures since then have been reclining figures' (quoted in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London, 1968, p. 151). David Sylvester described the genre in a manner particularly relevant to this sculpture: 'They are made to look as if they themselves had been shaped by nature's energy. They seem to be weathered, eroded, tunnelled-into by the action of wind and water. The first time Moore published his thoughts about art, he wrote that the sculpture which moved him most gave out "something of the energy and power of great mountains" [...] Moore's reclining figures are not supine; they prop themselves up, are potentially active. Hence the affinity with river-gods; the idea is not simply that of a body subjected to the flow of nature's forces but of one in which those forces are harnessed' (D. Sylvester, Henry Moore, New York & London, 1968, p. 5).

While Moore was working on his Shelter Drawings during the Second World War he became increasingly absorbed in the manner in which drapery could be made to denote sculptural volume. In part the enormous sculptural effects that could be achieved by draped figures had been inspired by Classical art, particularly some of the Parthenon figures. Moore noted that the shelter drawings caused him to look at and use drapery. Quoting Moore, David Sylvester considers drapery – accentuated in the present work around the figure's legs – a form of contour making which assists in the successful integration of the sculpture into its surrounding landscape. Moore uses 'the folds to create a variant of the metaphor of the figures as a landscape [...] to connect the contrasts of sizes of folds, here small, fine and delicate, in other places big and heavy, with the form of mountains, which are the crinkled skin of the earth' (ibid., p. 109).

For Moore, the use of drapery emphasised the tension of the covered form. Over time he began to treat drapery itself as an element formed by highlighting the curves and ruffles of the blanket. In this way, 'The wrinkles and crinkles of the drapery at one stage began to remind me in close-up of mountain ranges' (J. Hedgecoe (ed.), op. cit., p. 204). Moore has almost come full circle in his art and by 1982 the hills and crags represented by his early reclining figures are now linked to the curved solidity of his later sculpture.

Other casts of this work are at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Caracas and the Henry Moore Foundation in England.

Henry Moore (1898 - 1986), Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps, bronze. length: 72.4cm. 28 1/2 in. - height: 65cm. 25 5/8 in. Executed in 1956 and cast in bronze in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist's proof. Estimate 500,000 - 700,000 GBP. photo courtesy Sotheby's

The present bronze belongs to a series of seated figures that Moore created whilst thinking about a suitable sculpture he was commissioned to make for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. Moore was at odds with the practice of completing a sculpture for an existing building as a simple enhancement to the architecture, and thought of his sculpted figures as independent works of art that needed to be seen at all angles and not as an adornment positioned against a surface.

Creating an architectural element for the sculpture itself – the stairs, in the case of the present work – was his solution to this problem. The steps not only place the figure in a predetermined setting, they also create an independent and private space in which the seated figure exists.

While the image of a woman seated on steps was not chosen for the final UNESCO work, it was developed into several sculptures in their own right, including the present work.

Discussing Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps, Julie Summers wrote: 'This particular work is significant in that it bridges the gap between the draped figures of two or three years earlier, which had resulted directly from Moore's first visit to Greece in 1951, and the later figures set against architectural backgrounds. The use of steps gave him the possibility to explore placing a figure on an architectural feature without wholly obscuring the background. In the final monumental version of this sculpture the steps have been quite dramatically reduced to give the figure prominence' (J. Summers in D. Mitchinson (ed.), op. cit., pp. 253-254).

In the present version however, it is the combination of the rhythmic lines of the woman's dress and the cascading pattern of the steps that makes this a wonderfully dynamic work.

Other casts of this work are in public collections including the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Milwaukee Art Center.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F59%2F577050%2F40567337_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F97%2F14%2F577050%2F40293377_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F21%2F577050%2F38930361_p.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F61%2F14%2F119589%2F112627128_o.jpg)