Imperial Treasures Soar at Sotheby's Sales in Hong Kong

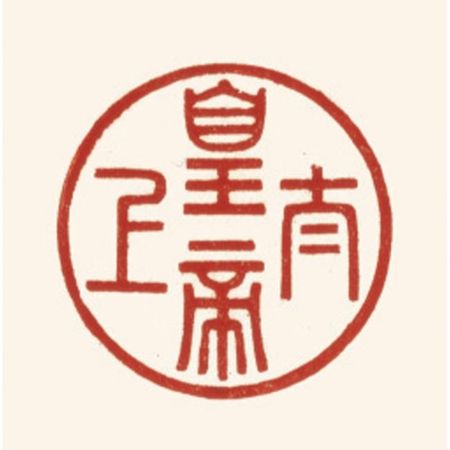

HONG KONG.- Yesterday at Sotheby’s Hong Kong Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art Spring Sale 2010, An Important and Superb Imperially Inscribed ‘Tai Shang Huang Di’ White Jade Seal, Yubi Mark and Period of Qianlong fetched HK$95,860,000 / US$12,289,744, establishing a world record for white jade and Imperial seal at auction. Previous record was also achieved by Sotheby’s Hong Kong when the jade seal commanded HK$46,247,500 / US$5,918,293 in October 2007.

Bidding opened at HK$30 million, and after 6 bids a phone bidder shouted out a bid of HK$50 million. The furious bidding continued for some time and after a total of 16 very frenzied bids which lasted for a tension-filled ten minutes, the seal was eventually sold to a room bidder for an astonishing hammer price of HK$85 million (HK$95.86 million including buyer’s premium),

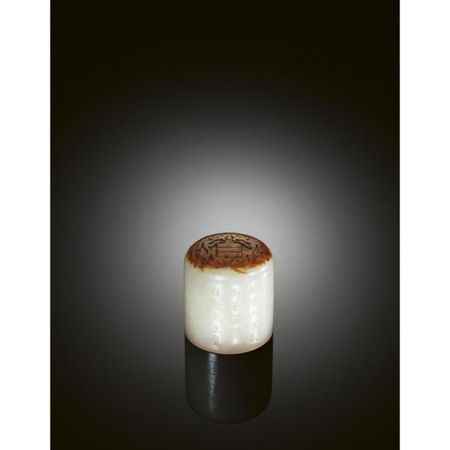

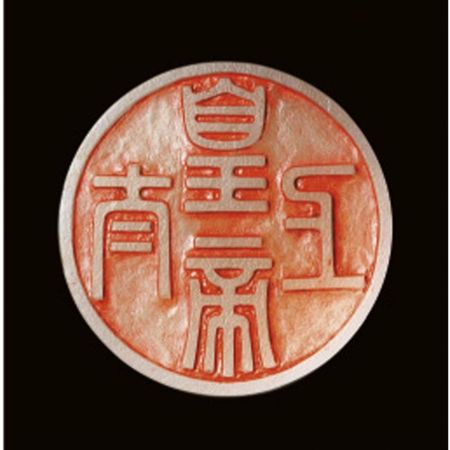

An Important and Superb Imperially Inscribed ‘Tai Shang Huang Di’ White Jade Seal, Yubi Mark and Period of Qianlong sold for 95,860,000 HKD. Photo: Sotheby's

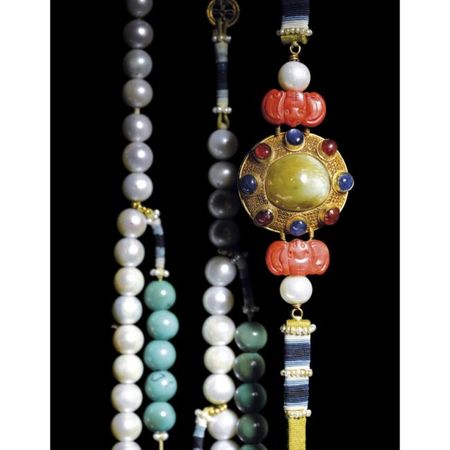

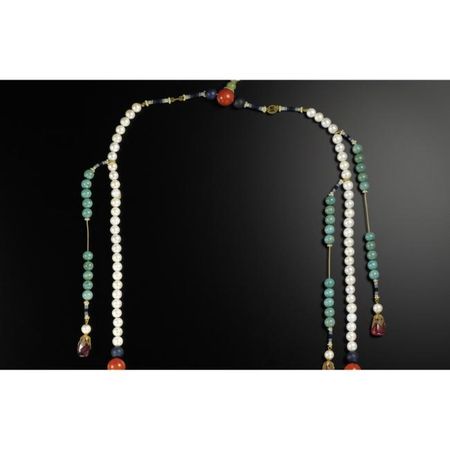

Another top lot – a magnificent ceremonial court pearl necklace (Chaozhu), Qing dynasty, 18th century sold for HK$67,860,000/US$8,700,000 to a bidder over the telephone, eight times the high estimate (HK$12 million/ US$1.55 Million), setting a world record for any Imperial jewel at auction. Started out at the opening bid of HK$5 million, this star lot was competed furiously by 4 telephone bidders and 1 bidder in the saleroom. After a total of 61 bids, it went under hammer at HK$60 million and was bought by a telephone bidder at the staggering price of HK$67.86 million/US$8.7 million (premium inclusive).

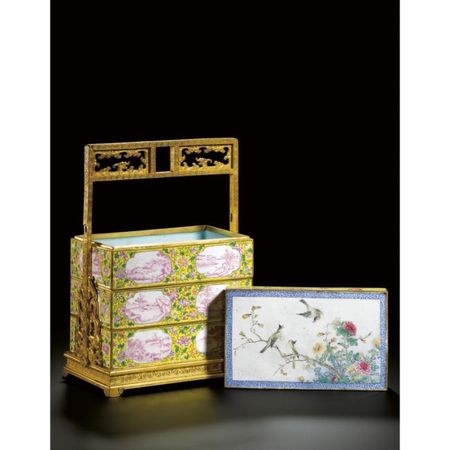

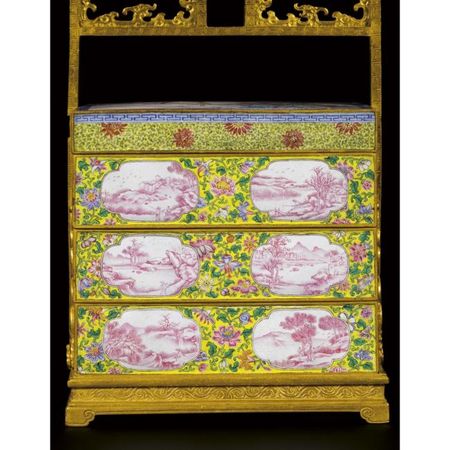

Also of note is an outstanding and extremely rare three-tiered Beijing enamelled box, mark and period of Qianlong sold for HK$27,540,000/US$3,530,769, setting a world record for a Beijing enamel ware at auction.

In The Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection - Objects Of Contemplation sale, an Imperially Inscribed Bamboo-Veneer Ruyi-Sceptre, Qianlong Period sold for HK$15.78 million / US$2 million (Est. HK$13-15 million), achieving a world record for a carved bamboo and a ruyi-sceptre at auction.

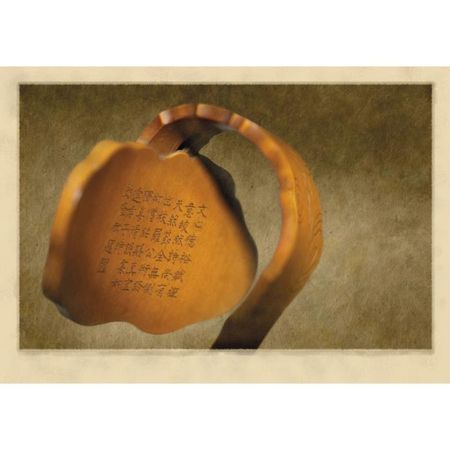

An Imperially Inscribed Bamboo-Veneer Ruyi-Sceptre, Qianlong Period sold for 15,780,000 HKD. Photo: Sotheby's

the smooth, golden bamboo-veneer surface carved with a naturalistic curved lingzhi stalk terminating with a large head with an attendant fungus on the top, the decoration incised in low-relief on three separate planes, the knotted and gnarled, slender stalk with further minor shoots growing from the base and on the sides, the underside of the lingzhi head carved with a poetic inscription by the Qianlong Emperor in kaishu script, followed by Qianlong yuti ('Imperial composition of the Qianlong emperor' and the seal Guxiang ('Ancient fragrance') - 34.7 cm., 13 5/8 in.

PROVENANCE: Bluett and Sons Ltd., London, 1983-1985.

EXHIBITED: Arts from the Scholar's Studio, Fung Ping Shan Museum, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1986, cat. no. 121.

NOTE: The poem inscribed on the present sceptre is translated by Prof. Richard John Lynn as follows:

'My literary mind is that of the rhapsodies of Deyu,

and my sense of Chan is that of the poetry of Jiaoran.

Moreover, I possess perfectly natural joints,

and am wholly free of protruding side branches.

The magic arts of Luo Gongyuan are but fantasies after all,

but the gift of Sengshao is a truly suitable thing.

I only like it where pure conversation takes place,

as when I meet with noble men.'

Qianlong yuti ('Imperial composition of the Qianlong Emperor')

The poem titled Zhu ruyi ('The bamboo Ruyi Sceptre') is recorded in Qianlong yuzhi shiji ('Collected Poems of the Qianlong Emperor'), vol. 2, 63 juan, and is dated between the 10th day of the 4th month and the 28th day of the 4th month of the bingzi year (equivalent to 1756).

Qianlong in his poem refers to Deyu or Li Deyu (787-850) of the Tang dynasty who served as prime minister and was also famous as a writer of poetry and prose. He wrote beautiful rhapsody (fu) described by the emperor as wenxin or 'literary minded' which is possibly a pun for the word wenxin meaning 'the core of my grain' implying that the bamboo grain is robust and strong just like Li's rhapsodies. However, more importantly, Li was a man of eminently high moral principles (dajie) to which Qianlong alludes in his poem using the expression tianran jie ('natural joints') a reference to Li's 'heavenly endowed moral integrity'.

Jiaoran (730-799) was a monk-poet from Changcheng, Zhejiang province, with the secular name Xie Zhou. He was deeply steeped in the Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian traditions and resided in the Miaoxi temple on Xu Mountain in Wuxing. He became famous for his literary criticism and was a key participator in the Classical Prose Movement of the late Tang dynasty. Jiao, through his work, conveyed the meaning of Chan (Zen) Buddhism. His poems describe the truth about consciousness, contemplation and enlightenment. Qianlong, a devote Buddhist, spent many hours in his study reading the poems of Jiaoran and associated himself with the notion that his 'sense of Chan' was on the same level as his.

The third historical figure mentioned by Qianlong in this poem is Luo Gongyuan, a Daoist priest, who according to legends, used his magic to help Emperor Xuangzong (712-755) meet the beautiful Consort Yang Guifei in his afterlife. The poem further mentions Sengshao, who was also a priest and had compiled the work Hualin Fodian zhongjing mulu ('The Catalogue of the Scriptures Kept in the Buddha Hall of Hualin Palace') in 513 on the orders of the Wu emperor of the Liang dynasty. He was a learned monk who lived in recluse and gave up his hermitage so that it could be reconstructured and used as a Buddhist temple. Qianlong mentions 'the gift of Sengshao' which is the famous Qixia si ('Perched among Rosy Clouds Temple').

By comparing himself with famous figures in antiquity, Qianlong was setting an example for himself and for others to follow. He wrote that his preference was 'pure conversation' insinuating that Li Deyu and the others were men who were free from the taint of the mundane, political and personal ambitions and all worldly concerns that he himself had to experience on daily basis.

According to Prof. Lynn, in the poem Qianlong seems to be writing as if he were the bamboo ruyi, his viewpoint acting both for it and for himself. It can safely be assumed that the poem was written for this particular sceptre.

The technique of bamboo-veneer (zhuhuang) was developed during Qianlong's reign. It involves taking the inner wall of the bamboo stem which is of light yellow colouration and applying it over a wood core which is then left plain or carved in shallow relief to achieve an elaborate decoration, often, in a two-colour effect. See an elaborately carved bamboo-veneer sceptre decorated with jade pieces illustrated in The Palace Museum Collection of Elite Carvings, Beijing, 2004, pl. 55.

An outstanding and extremely rare three-tiered Beijing enamelled box, mark and period of Qianlong sold for 27,540,000 HKD. Photo: Sotheby's

sublimely crafted, the rectangular box composed of three removable interlocking trays and a cover supported in a gilt-bronze frame, the top of the cover elegantly enamelled on a white ground with three mynah birds shown seated and flying amidst brightly coloured chrysanthemums and aster flowers, framed within a dense blue foliate scroll border, the sides with a band of key-fret above pink detached flower heads scattered on a lemon-yellow ground with grey foliate scrolls, the three trays all similarly decorated with two quatrefoil panels on the longer sides and a single panel on the narrow sides, each containing a fine puce-enamelled landscape vignettes, all reserved against an assortment of flowers borne on a leafy-green scroll, the flowers including lotus, camellia, aster, begonia, and hibiscus all picked-out in pink and blue enamels reserved on a matching lemon-yellow ground, the interior and base enamelled in turquoise blue, the underside inscribed with a four-character mark in dark blue enamel set within a double square, supported upon a gilt-bronze frame with the struts on the sides formed from two pairs of confronting gui dragons, the openwork handle similarly decorated with a pair of deconstructed gui dragons in profile framing the interior, the edges chased with an undulating foliate scroll, the box secured to the frame by a slender lock running through the cover - 19.2 by 13.5 by 8.5 cm 7 1/2 by 5 1/4 by 3 3/8 in.

PROVENANCE: A French Collection, by repute.

NOTE: By the 18th century, the technique of enamelling on metal reached its peak, reflecting the very high skills of court artists employed by the Enamelling Workshop and the extravagant taste of the emperor. The present tiered box is a fine example of perfection of style and technique. The enamelling is superbly rendered with much attention paid to the smallest detail such as the animated and realistic depiction of the birds and the beautiful and naturalistic rendering of the flowers. The panel on the cover is decorated in a painterly manner typical of court paintings of birds and flowers seen on Imperial porcelain; for example see a Qianlong dish included in The Special Exhibition of Ch'ing Dynasty Enamelled Porcelains of the Imperial Ateliers, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1992, cat. no. 116, also with a similar flower scroll design on a yellow-ground around the rim interspersed with landscape vignettes in puce enamel.

A comparable tiered box, decorated with landscape scenes in panels is illustrated in Michael Gillingham, Chinese Painted Enamels, Oxford, 1978, pl. 53. The present box is reminiscent of a tiered octagonal-form winter inkstone box, sold in these rooms, 27th April 2003, lot 4, the cover painted in the classical Guyuexuan-style with geese and quails amongst flowers, with side panels densely decorated with flower scrolls on a yellow-ground. See also a melon-shaped box enamelled with landscapes, Western-style figures and flowers within cartouches, surrounded by floral scrolls on a yellow-ground, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Metal-bodied Enamel Ware, Hong Kong, 2002, pl. 208.

Beijing Palace Museum Researcher, Mr. Xia Gangxi, has examined this piece and commented that the enamelled box "is elegantly proportioned and of expandable compact form." And the colours are "pure yet luxurious." He calls the painting on the box "well executed with a lively composition" and most importantly, the box is "not only an exceptional piece among the imperial enamelled vessels, but also an extremely rare example with no previously published comparison."

The Qing Ceremonial pearl necklace sold for HK$67,860,000/US$8,700,000. Photo: Sotheby's

consisting of a strand of 108 freshwater Eastern pearls divided into groups of twenty-seven by four fotou (Buddha heads') large coral beads flanked by pairs of lapis-lazuli, the foutou at the back connected to a green gourd-shaped foutouta ('Buddha head stupa'), suspending a gold filagree beiyun ('back cloud') oval plaque inset with a large chartreuse quartz cabuchon encircled by smaller spinel and sapphire cabochons, the reverse with a gold cloud design against a fine gold filagree, flanked by a pair of coral bats and two pearl beads, terminating with a large eggplant-shaped red tourmaline (rubellite) bead with a gold filagree calyx, suspended from a yellow silk tape wrapped with blue and white cords and tiny seed pearls, the three jinian strands of turquoise beads each further suspending a similar red tourmaline eggplant-shaped drop, cinnabar lacquer box - diameter 134 cm., 52 3/4 in. weight: 330 g. pearl diameter 9.60 - 10.65 mm.

PROVENANCE: From a Japanese Collection, by repute.

NOTE: Accompanied by a Pearl Report from Gubelin Gem Lab, Lucerne, Switzerland, certificate no. 0911002, stating that the pearls are "natural freshwater pearls."

The Emperor's Magnificent Eastern Pearl Court Necklace (Chaozhu) by Hajni Elias

The importance of the present court necklace or chaozhu is immediately evident in the use of large white and flawless Eastern pearls – one of the most treasured and precious materials employed for the wardrobe and paraphernalia exclusively made for the emperor and his family members. The seated portrait of the Yongzheng emperor wearing a formal court attire, in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, and included in the National Palace Museum's recent grand exhibition Harmony and Integrity. The Yongzheng Emperor and His Times, Taipei, 2009, pl. I-3 (see p. 52) depicts Yongzheng wearing an almost identical, if not the same chaozhu as that in this catalogue. While chaozhu were made in a variety of precious and semi-precious materials, with a number of examples in important museums and collections, those made with dongzhu or Eastern pearls are extremely rare. There are only five other known Eastern pearl chaozhu in China, all located in the Palace Museum in Beijing. One necklace is from the Shunzhi period and the four others are all 19th century. There is a sixth one possibly located in the Shenyang Palace Museum. The National Palace Museum in Taiwan does not own any. The Eastern pearl chaozhu is considered to be of the highest grade of cultural importance.

A painting on silk of an Imperial pearl necklace, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, is published in Gary Dickinson and Linda Wrigglesworth, Imperial Wardrobe, Toronto, 2000, p. 158. See further five chaozhu in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, included in the museum's special exhibition of Ch'ing Dynasty Costume Accessories, Taipei, 1986, cat. nos. 54-58, made of gold, turquoise, amber, jade and fruit stone. The chaozhu was introduced as part of the official ceremonial attire by the Qing rulers, a design that was based on the Buddhist rosary such as the Ming example illustrated in Jewellery and Costumes of Ming Dynasty, Beijing, 2000, pl. 195. The earliest basic rules relating to the Imperial wardrobe was set down by Abahai in 1636. After the Manchu conquest in 1644, his rules were revised and augmented. The new regulations were recorded in the Huangchao liqi tushi ('Illustrated Regulations for the Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Qing Dynasty'), an eighteen juan monumental manuscript that includes thousands of illustrations and lengthy text, scrupulously laying down all that concerns the 'proper' paraphernalia for the emperor and his court. Costume and jewellery are well represented in this manuscript for both men and women, starting with the emperor down through all the ranks of the imperial clan and the whole of the court and civil service. The emperor's own accessories are meticulously documented, with specific instructions given for four necklaces of different colours to suit the different types of occasions the emperor attended.1

According to the Huangchao liqi tushi the emperor's principal chaozhu was made of Eastern pearls. The significance of freshwater pearls to the Emperor cannot be emphasized enough. Eastern pearls were harvested from the three main rivers in Manchuria, the Yalu, Sungari and Amur. Hence they were treasured by the Manchu rulers for their association with their 'homeland'. Rules also specified that only the emperor and his family members were allowed to wear this precious pearl that was made into necklace or sewn into Imperial robes. The famous jifu belonging to Rongxian, daughter of the Kangxi Emperor, made of yellow silk and decorated with dragons embroidered with 100,000 Eastern pearls, was part of her dowry when she married Prince Wuergan in 1691.2 Another pearl-embroidered dragon robe belonging to the Qianlong emperor is now in the collection of the Capital Museum in Beijing.

Strict rules also applied to the number of pearls used for the making of chaozhu as well as the sequence of the setting of the beads. Necklaces consisted of 108 beads, with a bead of a different colour or material, called the fotou (Buddha's head), placed between groups of 27. Additionally, there are three strands called jinian extending at two sides and a decorative strap in the centre of the back. It appears that the use of pearl combined with four large beads made of coral in between two lapis-lazuli beads, and the jinian strung with turquoise was also specified. The crown prince was allowed to use any semi-precious stones strung on apricot-yellow thread, while the emperor's sons and imperial princes of the first two degrees were supposed to use amber with golden-yellow strings, while everyone else belonging to the court would use any stone with blue-black thread.3

The meticulously executed filigree work on the large oval plaque embellished with precious and semi-precious stones is reminiscent of that seen on a number of Imperial gold pieces, including the gold ewer and cover, from the Kempe Collection, sold in these rooms, 11th April 2008, lot 2305; and on a butterfly-form gold brooch decorated with a variety of colourful stones, from the Qing court collection and still in Beijing, published in Zhongguo meishu quanji, vol. 10, Beijing, 1987, pl. 199. Compare also three Qianlong period boxes inlaid with precious stones on a gold filigree ground illustrated in Masterpieces of Chinese Miniature Craft in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1971, pl. 41. The workmanship of gold accessories and vessels is of the highest quality suggesting that they were made in the Palace Workshop located in the Forbidden City.

1 See Margaret Medley, The Illustrated Regulations for Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Ch'ing Dynasty, London, 1982, p. 17.

2 Mo Chuang, 'Pearl robe of the Emperor K'ang-his's Daughter', China Features, Beijing.

3 Gary Dickinson and Linda Wrigglesworth, Imperial Wardrobe, Toronto, 2000, p. 158.

of small circular form, superbly carved in low relief with the triagram qian between a pair of confronting qilong, the sides deftly incised with a poem ending with the date Qianlong Bingchen chun yubi (corresponding to 1796), the seal face deeply and crisply carved with the characters tai shang huang di ('Treasure of the Emperor Emeritus') in zhuanshu, the stone of a translucent fine white colour with an area of russet skin on the top skillfully utilised to enhance the carving - 4.5 cm., 1 3/4 in.

PROVENANCE: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 9th October 2007, lot 1301.

NOTE:

"Tai shang huang di, Treasure of the Emperor Emeritus" by Guo Fuxiang, Department of Palace History, The Palace Museum, Beijing

The Qianlong Emperor had the longest reign period in Chinese history and also enjoyed one of the longest life spans. He inherited the dynasty from his ancestors, and built on the prosperity and power, creating a dynasty of great splendor during his reign. For his legacy he had objects made to reflect the different stages and the major events and turning points in his life. A few years ago, I published a book titled The Treasure Seals of Emperors and Empresses of the Ming and Qing Dynasties which was an exclusive study of the treasure seals of Emperors and Empresses. In the book I summarized the characteristics of Qianlong's seals, one of which is that his seals were made to record meritorious events. During Qianlong's reign seals were carved to commemorate special state events and family happenings. These seals were then re-carved in great numbers. If we lined up these seals according to the year they were made, we can clearly see all the major state events and family happenings of his reign.

The important circular seal carved with the "Treasure of the Emperor Emeritus", presented in this sale, is a work of great significance. This seal is made of a circular white jade that has a russet skin. The seal is carved with the trigram qian between a pair of confronting qilong in low relief. The face of the seal is deeply carved in zhuanshu with the four characters tai shang huang di "Treasure of the Emperor Emeritus." Qianlong's poem titled "Treasure of the Emperor Emeritus' is carved on the side of the seal. The white jade used for making this seal is of a fine lustrous colour. The carving of the poem is naturalistic and refined and closely follows the emperor's writing style. The seal is recorded in the Collection of Qianlong's Treasures. Considering the quality of the jade, its size and the carving, it is evident that the present seal is the seal recorded and is the genuine Qianlong treasure seal.

In order to understand and appreciate this seal, we have to know the history of the Emperor Emeritus "tai shang huang". Emeritus means 'the most supreme', a term of extreme respect; and together with the word "huang" means that 'its virtue is more supreme than the emperor'. Therefore, the four characters together refer to someone 'whose virtue is even more supreme than the emperor'. The term "tai shang huang" first appeared during the Qin Dynasty. According to the records of Shi Ji by Si Ma Quan, after the first Emperor, Qin Shi Huang, united the six kingdoms, he gave his deceased father, Zhuang Xiang, the title "tai shang huang". The Shi Ji also records that after Liu Bang of the Han Dynasty became the emperor, he showed extreme respect towards his father, Liu Tai Gong. According to legends, one day, his father's housekeeper said the follows to his father:

"Heaven does not have two suns, neither should the earth have two kings. Although the present emperor is your son, nevertheless, he is the head of the country. Although you are the father of the emperor, you are his subject. How can the emperor kowtow to his subject? If this continues, your prestigious position will not last long.''

When Liu Bang visited his father, Liu Tai Gong went to greet him outside the front door with a sweep in his hand. He humbly led his son into the house. Seeing this, Liu Bang was very surprised and asked why his father was acting so humble. Liu Tai Gong said, "You are the emperor of the people, I am your subject, how should law and regulation be changed because of me!" Thus Liu Bang issued an imperial decree to honour Liu Tai Gong as the "tai shang huang". Liu Tai Gong was the first person in the Chinese history to become an honored "tai shang huang" despite not being an emperor himself.

The significance of the "tai shang huang" was later changed and become associated with the handing over of the imperial throne. Qianlong became a "tai shang huang" after he abdicated his throne. Hence, this was a major turning point in his life and to commemorate this he ordered the making of this seal.

According to records, when Qianlong became the emperor he promised to rule the nation for sixty years, after which he would choose his successor and abdicate the throne. He kept his promise and in the year of his sixtieth reign, on the third day of the ninth month, at the age of 85, he gathered his sons and grand-sons, ministers and officials, and declared that he was handing over his throne to the 15th prince, Jia Yong Yan, and named the year after that as the first year of the Jiaqing reign. An order was issued in which Qianlong declared that he would go to Taihe Dian (Hall of Great Peace) and personally hand over the treasure seal. He also declared himself "tai shang huang." Thus Qianlong completed his 60 years as the Emperor and became the last "tai shang huang" in Chinese history.

In his preparation to become the "tai shang huang", on the 28th day of the ninth month, Qianlong issued the following edict: "After I resign, the number one jade treasure with the character xi should be used and engraved with the characters tai shang huang di.''

The seal mentioned in this edict is the largest amongst the "tai shang huang di" seals and can be found in the Palace Museum collection. Under Qianlong's instructions, the carvers working in the Palace made several "tai shang huang di" seals, amongst which one of them is the present seal.

According to the Collection of Qianlong's Treasures, over twenty "tai shang huang di" seals were made. The majority of these seals are still kept in the Palace Museum. The present seal is unusual for its circular form. The majority of seals are square or rectangular in shape, and this is the only circular seal.

This circular seal was possibly the last seal made in this series. The material of this seal is of the highest quality and is reminiscent of archaic jade. Qianlong often mentioned it as the "White Han Jade". Both the carving and the jade are after Han jade seals. The shape of this seal reminds me of another circular-form Qianlong seal, carved with the four characters "gu xi tian zi" (Heavenly Son of rare seventy). According to archival records, this seal was partially made from using archaic jade.

The trigram "qian" carved on this seal is also special to the Qianlong emperor. This ba gua pattern can be found engraved on many of Qianlong's seals as well as on other important objects. The side of the seal is carved with Qianlong's poem of "The Emperor Emeritus". Qianlong wrote this poem especially for this seal and it reflects his true feelings at the time. The poem was written in the first year of Jiaqing's reign (equivalent to 1796A.D.) when Qianlong became the 'Emperor Emeritus'. The poem can be translated as follows:

Treasure of the Emperor Emeritus

Since ancient times, fathers of ruling emperors have been addressed

With grand titles and exemplary epithets - this I say is not right.

Though these last six decades have been cause for great congratulation and rejoicing,

I'm ashamed I've had no leisure to add my own antithetical couplets to them.

Throughout my life I've asked myself how virtue might be achieved.

So that my guidelines be spoken of forever - resulting, I pray, in great prosperity.

With window bright and desktop clear, I read the "Western Inscription".

Just now as the moments come when I cherish all the time I have left

The last two lines of the poem reveal Qianlong's thoughts. In his study, where the window let in light and the desktop was cleared, he examined the famous scroll of Xi Ming (Western Inscription) by the great Song philosopher Zhang Dai. Qianlong's poem has been carved on many of the "tai shang huang di" seals and therefore its significance is understandable and needs no further explanation.

Being one of the most important seals of Qianlong's life as "the Emperor Emeritus", this circular seal was often used on books and paintings kept in the Neiwufu. For example, it can be found on Han Huang's Painting of the Five Oxen and on Wang Xianzhi's Mid-Autumn Calligraphy, which are both kept in the Palace Museum. It can also be found on Tang Yin's Painting on Tea Drinking. The present seal was often used together with the seal of 'gu xi tian zi'. It is possible that the two seals were made as a pair (see another painting with both seals.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)