Miniature Chinese Art Makes World Record Prices at Bonhams

A Baroque pearl, crystal, glass and gold Imperial snuff bottle, attributed to Guangzhou, 1760-1799, is presented at a Bonhams in Hong Kong, China. EPA/ALEX HOFFORD,

LONDON.- Bonhams Hong Kong today celebrated the first-ever “Golden Gavel Auction” in its history, when part of the world’s finest collection of important Chinese snuff bottles, the Mary and George Bloch Collection, sold 100% and achieved world record prices. Against presale estimates of HK$20,000,000 (£1.8m), the sale total was HK$66,146,800 (£5.8m), with every one of the 140 rare bottles successfully sold. This figure was double the previous sale total for a single-owner snuff bottle auction held in New York on 19 March 2008.

Auctioneer Colin Sheaf, Chairman of Bonhams Asia, commented: “This is the finest auction of Chinese art which Bonhams has held in Asia, and the record prices proved that the market for Chinese art remains very strong for the most important pieces”.

As expected, the star of the auction was lot 129, one of the most beautiful bottles in private hands ever made for the Imperial Court of 18th Century China. Estimated at HK$1,800,000 – 3,000,000, international bidders from mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore and the UK battled the bidding up to a final figure of HK$9,280,000 (£821,383,000), a new world record price for a snuff bottle.

A Beijing enamel European-subject snuff bottle. Imperial, palace workshops, 1736–1760, Qianlong blue-enamel mark and of the period. 4.22cm high. Estimate: HK$1,800,000 - 3,000,000. Sold for HK$9,280,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 6, no. 1076

銅胎琺瑯彩西洋人物鼻煙壺

御製品,宮廷作坊,北京,藍琺瑯彩書乾隆年款,1736~1760

Gathering Clouds

Famille rose enamels on copper, with gold; with a flat lip and slightly recessed concave foot surrounded by a protruding flat footrim; painted on each main side with a foliate panel of European subjects, one a woman and a young boy with an elaborate building and trees in the background, the other a woman with a basket of flowers and fruit and a young boy with buildings and the tree-clad banks of a stream behind her, the panels surrounded by a formalized floral design; the neck with a formalized floral band; the foot inscribed in blue regular script, Qianlong nian zhi (Made during the Qianlong period), the interior covered with a patchy, turquoise-blue enamel, the exposed metal all gilt

Imperial, palace workshops, Beijing, 1736–1760

Height: 4.55 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.70/1.13 cm

Stopper: gilt bronze, chased with a formalized floral design; probably original

Condition: perfect and in kiln condition, with even the original gilding intact; some minor original pitting of some of the enamels, particularly the olive-green around the neck and very minor separation lines visible only under magnification. General relative condition: extraordinarily good

Provenance: A. W. Bahr

Robert H. Ellsworth

Christie's, New York, 9 May 1981, lot 419

Hugh M. Moss, Ltd (1981)

Paula J. Hallett (1986)

Hugh Moss (HK), Ltd (1986)

Published: JICSBS, Winter 1986, front cover

Kleiner 1987, no. 2

Galeries Lafayette 1990, p. 7, no. 1

Illustrated London News, Summer 1990, p. 49

Orient Express Magazine, Summer 1990, p. 49

Prestige, Summer 1990, p. 49

E & O Magazine 2, no. 4 (1994), p. 62

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, no. 6

Kleiner 1995, no. 3

Treasury 6, no. 1076

Exhibited: Sydney L. Moss Ltd., London, October 1987

Galeries Lafayette, Paris, April 1990

Creditanstalt, Vienna, May–June 1993

Hong Kong Museum of Art, March–June 1994

National Museum of Singapore, November 1994–February 1995

British Museum, London, June–October 1995

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, July–November 1997

Commentary: The extraordinary artistry of painted enamels at the palace workshops during the early Qianlong period can be seen in so many aspects of surviving examples. There is a wide range of subjects, and where a subject is repeated it is always recomposed as a fresh, vital work of art. Given the quantity of bottles that must have been produced with the theme of a European mother and child, for instance, this speaks of a very high level of artistic commitment. It would have been so easy to simply make a number of bottles of the same composition, from the same preparatory drawing, but this was rarely done at the palace workshops prior to the second half of the Qianlong period, and even then sparingly and only in the case of a few designs.

The variation in early palace enamel designs, even of similar themes, is spectacularly demonstrated here. By introducing dark clouds to the common motif of mother and child, the artist has created an entirely different mood, enlivening a standard theme. Elsewhere, skies are left in pale blue and white to indicate clouds in a blue sky, or simply shaded a very pale blue for a cloudless sky, both idyllic. The effect of the brooding, grey sky suggesting a gathering storm is dramatic, starkly emphasizing the white buildings and their European style and the slightly melancholic expressions of the women. Portraiture in China, other than of certain deities, rarely depicts smiling faces, and the standard for women in the Qing dynasty was for either inscrutability or a melancholic, wistful look. None of the European women depicted on enamels is smiling, and yet we get the impression that they are happy because of the idyllic setting. Gathering, brooding clouds change all that, and we have only to compare this scene to Treasury 6, no. 1077 to fully grasp their effect.

Another feature of these early-Qianlong palace masterpieces is the extraordinary variation in the borders and surrounding decoration that, despite being peripheral detail, commanded equal artistic commitment. Not until the mid-reign do we begin to see repeated borders and the repetition of certain compositions with little variation between them, hinting at the beginning of a reduction in artistic standards and a shift to the more decorative intent of some of the enamels from the last third of the reign. Technically, the art of enamelling may remain the same or, in the case of enamelled glass, improve during the mid-century, but artistically the first third of the reign represents the zenith of Qianlong enamelling. The borders here are spectacular. They employ a visual trick similar to that seen in the main panels, setting the design against a darker ground to create contrast and emphasis. The yellow dots filling the olive-green ground at the shoulders and around the base and the similar colour scheme for the floral band around the neck are extremely rare and appear only on this example and in a small way on Treasury 6, no. 1077. The palace artists, designers, and administrators responsible for enamels in the first two decades of the reign were obviously revelling in their newfound technical skills and responded to the intense interest of the emperor with astonishing artistry. In bottles such as this, it shows. Like most enamelled metal bottles from the period, this example appears to the naked eye to have fired to perfection, but as usual, magnification reveals a few tiny areas of pitting in the enamels.

樓峻似人白,秋陰與天低

銅胎施琺瑯彩;平唇、略斂凹底、突出平底圈足;腹兩面開光各別,彩繪西洋人物母子圖、母女圖,背後繪洋式樓與叢樹,頸部繪花卉紋一週,開光間為歐洲洛可可式的葉紋飾;底藍書雙行"乾隆年製"四字楷款;腹內壁施不均的松石藍琺瑯彩,露胎處描金

御製品,宮廷作坊,北京,1736~1760

高:4.55 厘米

口經/唇經:0.70/1.13厘米

蓋:描金的青銅,起花縟麗,大概為原件

狀態敘述:完善,出窯狀況,連原來的描金也保存得完好;琺瑯彩表面呈現原有的瘡孔,特別是在頸部的橄欖褐色地,亦有肉眼看不見、微小的收縮裂縫;一般相對的狀態:非常完好

來源:A. W. Bahr

Robert H. Ellsworth

佳士得,紐約,1981年5 月9日,拍賣品號419

Hugh M. Moss, Ltd (1981)

Paula J. Hallett (1986)

Hugh Moss (HK), Ltd (1986

文獻:《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1986冬期,封面

Kleiner 1987,編號2

Galeries Lafayette 1990, 頁7,編號1

Illustrated London News, 1990年夏期,頁49

Orient Express Magazine, 1990年夏期,頁49

Prestige, 1990年夏期,頁49

E & O Magazine 2, 第4號 (1994年),頁62

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, 編號6

Kleiner 1995, 編號3

Treasury 6,編號1076

展覽﹕Sydney L. Moss Ltd, 倫敦, 1987年10 月

Galeries Lafayette, 巴黎,1990年4月

Creditanstalt, 維也納, 1993年5月~6月

香港藝術館,1994年3 月~6月

National Museum of Singapore, 1994年11月~1995年1月

大英博物館, 倫敦, 1995年6月~10 月

Israel Museum, 耶路撒冷, 1997年7月~11月

說明:乾隆早期宮廷作坊作的琺瑯西洋母子鼻煙壺,多不勝數,但雖然是同一個題材,並不是千篇一律。不知道是設計專家預備畫稿還是琺瑯匠臨時想方設法,但本壺也代表這種創新精神。譬如說,畫師添上了陰雲,襯托正在作白日夢的婦女的金髮玉面,也使這兩幅圖像與其他母子圖氣氛迥然不同。繪畫中的明清婦女跟西洋女人不同,老是陰幽幽的,本壺的背景有使畫面的氣調柔和一些的效果,減輕異邦的感覺。

特別令人拍案叫絕的是開光周圍的花紋。到了乾隆中期才遇到飾邊的重複。在材料品質和技術能力方面,十八世紀中期也許稱得上高峰,特別是玻璃胎琺瑯彩領域內,但在藝術價值方面,乾隆間最初三十年才是高潮。開光外的暗色地有效地襯托洛可可式的葉紋飾,近底和頸部一周的橄欖褐色地純黃點絕無僅有,也顯示,當時所有跟琺瑯彩的技術革新有關係的設計專家、管理員、琺瑯匠等,因皇帝對他們的工藝和技術突破也那麼感興趣,一定要感恩圖報,不論大小要竭力盡能。

Other record prices included lot 140, an inscribed nephrite pebble-material snuff bottle which went for a world record price for any jade snuff bottle at HK$6,032,000 (estimate: HK$1,000,000 – 2,000,000); lot 132, an Imperial “famille-rose” ‘bird on branch’ enamelled glass snuff bottle, Qianlong mark and period, which sold at HK$5,248,000 (estimate: HK$2,000,000 – 4,00,000) a world record for any enamelled glass snuff bottle; lot 27, an Imperial famille-rose poreclain bottle, Qianlong mark and period, similar to others in the National Palace Museum, Taiwan, which sold at HK$3,960,000 (estimate: HK$1,400,000 – 2,000,000), a world record for any enamelled porcelain snuff bottle; lot 8, a double-overlay sapphire-blue and white glass ‘dragon’ snuff bottle which sold at HK$672,000 (estimate: HK$220,000 – 350,000), a world record price for any glass overlay snuff bottle; lot 34, an inside-painted rock-crystal snuff bottle which sold at HK$336,000 (estimate: HK$60,000 – 120,000), a world record for any inside-painted snuff bottle by Gan Xuanwen; and two other superb Imperial Beijing enamel bottles, lot 77, which flew past its estimate of HK$1,400,000 – 2,500,000 to make HK$4,200,000 and lot 67, which sold for HK$2,640,000 (estimate HK$1,800,000 – 3,000,000).

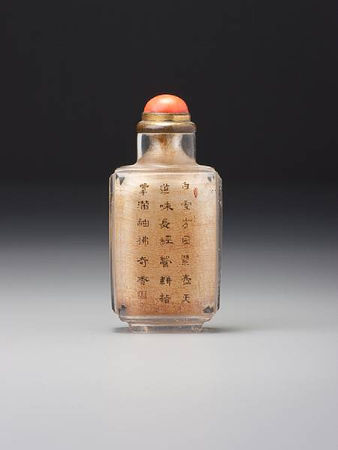

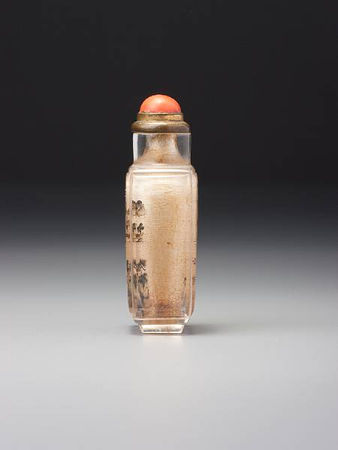

An inscribed nephrite pebble-material snuff bottle; Zhiting School, Suzhou, 1740–1840; 8.65cm high. Estimate: HK$1,000,000 - 2,000,000. Sold for HK$6,032,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 1, no. 125

閃玉石卵料人物風景鼻煙壺

芝亭流派,蘇州,1740~1840

'Stone like Gold' Suzhou Pebble

Nephrite of pebble material; carved with a continuous rocky landscape scene in which an elderly scholar walks past a lotus pond while another scholar is seen poised, with his brush in the air, having inscribed a rock face with the three characters shi ru jin (stone [prized] like gold), an attendant at his side holding his inkstone, with a pine tree and a wutong tree growing among the rocks and wisps of formalized clouds floating in the air

Zhiting school, Suzhou, 1740–1840

Height: 8.65 cm

Mouth: 0.62 cm

Stopper: jadeite, carved as a twig carved with leaves

Condition: minor trim to pine needles beside mouth, barely noticeable without a magnifying glass; five tiny chips to raised characters of the inscription; small chip on lotus leaf below old man with walking stick; nothing obtrusive

Provenance: Drouot (Millon Jutheau), Paris, 1 and 2 March 1984, lot 148 and front cover

Robert Hall (1987)

Published: Hall 1987, no. 53 and dust-jacket cover, front and back

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, no. 41

Treasury 1, no. 125 and front and back covers

Exhibited: Robert Hall Gallery, London, October 1987

Hong Kong Museum of Art, March–June, 1994

National Museum, Singapore, November 1994–February 1995

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1997

Commentary: There are very few Suzhou nephrite snuff bottle which have greater impact than this one. It is, quite simply, stunning. The pebble material has as richly marked a skin as any known pebble, with a thick outer layer of vivid, russet-brown giving way to a paler colour beneath, and the core material is half white and half an intriguing dark-brown speckled beige material. This is the nephrite equivalent of the extraordinary agate bottle in the J & J Collection (Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, no. 140) where a material miracle of nature has inspired the artist to extraordinary achievement.

"Cherish stone as if it were gold" is a common declaration of principle among the many Chinese who collect interesting stones or who prize fine stones for seal carving and other arts. And if it is to be carved, as little of the stone as possible is to be taken away. Here is the pronouncement of one connoisseur writing about tianhuang, 'field yellow', a famous variety of Shoushan stone from Shou Mountain in Fujian; this stone is particularly prized for seal carving:

Because tianhuang stone is so precious, most collectors would rather keep it in its natural, uncarved state than go at it with carving tools. Even if they are going to make a seal out of it, they will seek out a famous expert, and the expert seal carver himself will usually cherish the stone like gold, and rack his brains to avoid the unbearable, which would be to carve the whole thing (those three seals of the Qianlong emperor are exceptions—and actually a terrible waste). They will use relief carving or shallow relief carving to disguise or pick out the flaws in the stone, just to make it more charming.... (Yang Tianliang 1995, p. 521)

Could there be any better expression of the spirit with which our Suzhou artist has approached this nephrite pebble? In making this snuff bottle, he has tried to preserve as much of the pebble's true 'face' as possible. The gentleman inscribing the cliff with his message has made this intention explicit in words (though he does not deign to spell the full expression out for us), speaking for the carver to us across the ages.

The relief carving also shifts the real-life scene depicted to the realm of the art of the snuff bottle, where the available skin has dictated the difference in colour and the relief carving, and in which the relief merely stands for the prominence of freshly brushed ink and is no more intended as the substance of material reality than the scale of the tree behind the scholar or the formalized clouds which float in so powerful an abstract manner above his head. Together with the fluency with which everything is carved, this ambiguity between the objective reality of the real world and the subjective reality of the work of art is powerful and intriguing. This can also be seen in the relationship between the scholar and his attendant, which is sculpturally brilliant. Both are entirely believable as real figures, with superbly controlled, three-dimensional carving showing every fold of their garments, every nuance of expression, and yet both are posed for maximum abstract impact as well, which is not a paradox in Chinese aesthetics where artists have been creating abstract paintings made

up entirely of representational detail since as early as the twelfth century. The inscription is finished but the scholar stands poised with his brush apparently about to embark upon the third character, one hand holding his sleeve away from the rock surface so as not to smudge the ink as he writes. The attendant holds the inkstone tilted to such an angle that the already ground ink would run off immediately, and yet by doing so both the nature of the object and the sculptural movement are revealed far more powerfully than if it had been depicted in a functional manner. The placing and pose of the two figures link them with the inscription on the rock as a third element in a powerful, abstract composition which makes nonsense of the tiny scale of the scene and becomes monumental.

On the opposite side, the elderly scholar walks with a stick beside a lotus pond, with leaves and a bloom rising on long stalks from the rippling water. Each of the leaves and the bloom are carved using the darker surface skin, setting them in sharp contrast to the ground and to the lower layer used for a rock-face against which they partly grow. The bloom seems almost animated, facing the elderly sage as if the two were communing, as, indeed, they may well be. It was a common phenomenon for scholars on their countryside jaunts to pause and become engrossed in the minutiae of nature, and a 'conversation'

with a lotus bloom, in terms of deep communication with its inner qualities, was no more fanciful than a more conventional conversation with a fellow aesthete.

Throughout this extraordinary work of art, the control of the medium and confidence of expression are total. The sculptural detail has the fluidity of a master painting, and the finish is impeccable with each plane of relief perfectly separated from the next and powerful forms juxtaposed for maximum visual effect.

吐蕃卵石已如金,蘇州雕藝更可讚

閃玉卵石料;刻通體山崖景色,一正面有學士漫步蓮池畔,另一正面有學士剛好書"石如金"於石壁上,有侍者托硯,腹上部刻卷雲紋、松樹等

芝亭流派,蘇州,1774~1840

高:8.65 厘米

口經:0.62 厘米

蓋:翡翠,雕帶葉子的小枝

狀態敘述:口沿松針有所剪修,肉眼幾乎看不見,浮雕的字呈五個細小缺口,漫步老翁下邊的荷葉有小缺口,以上都不引人注目

來源:Druout (Millon Jutheau),巴黎,1984年3月1、2日,拍賣品號148、封面

羅伯特.霍爾(1987)

文獻﹕Kleiner 1987, 編號53,包書紙面、底

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, 編號41

Treasury 1, 編號125,封面、封底

展覽﹕Robert Hall Gallery, 倫敦,1987年10月

香港藝術館,1994年3 月~6月

National Museum of Singapore, 1994年11月~1995年1月

Israel Museum, 耶路撒冷, 1997年7月~11月

說明:這件令人驚奇的蘇州閃玉卵石料鼻煙壺體現著壺面上的學人所寫出來的道理﹕惜石如金。我們可以引用下面的話來說明這個想法﹕

由於田黃石甚為珍貴,故一般藏家寧可保持它的古樸自然的本來面目, 也不願在上面濫施刀刃。即便是刻印鈕,定要請名家高手,而刻鈕高手也往往惜石如金,挖空心思,他們不忍對之施以透雕(乾隆皇帝的那三枚印章是例外,其實是很大的浪費),而借用浮雕或淺浮雕(薄意)來剔除或掩飾田黃上的疵點,而使原石愈加瑰麗可愛......(楊天亮1995,頁521)

這很清楚地說明為甚麼鼻煙壺雕匠珍惜卵石料,閃玉卵石就是這個道理的縮影。加上本壺的雕藝的精緻,人物雕得栩栩如生,實在是不朽之寶。

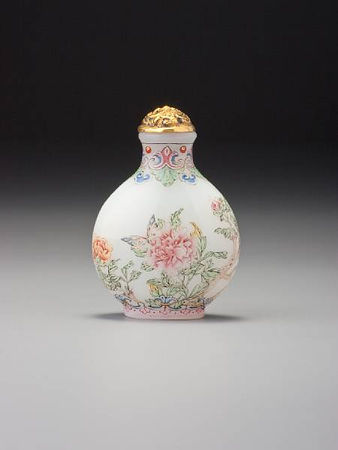

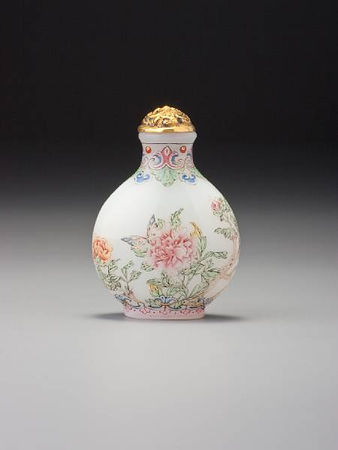

A 'famille-rose'-enamelled glass 'bird on branch' snuff bottle. Imperial, palace workshops, Qianlong blue-enamel mark and of the period, 1736–1760. 4.55cm high. Estimate: HK$2,000,000 - 4,000,000. Sold for HK$5,248,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 6, no. 1068

玻璃胎琺瑯彩白頭翁棲枝鼻煙壺

御製品,宮廷作坊作,北京,藍琺瑯彩書乾隆年款,1736~1760

Palace Desires

Famille rose enamels on semi-transparent milky glass; with a flat lip and slightly recessed flat foot surrounded by a protruding convex footrim; painted with a continuous scene of a bird perched on a leafy branch with asters growing nearby and a butterfly settling on the flower of a tree peony, with another bloom and budding branches nearby, the neck, shoulders, and the base with formalized bands incorporating lingzhi, the shoulders with additional pendant leaves, the outer footrim with pendant petals, the foot inscribed in blue regular script, Qianlong nian zhi (Made during the Qianlong period)

Imperial, palace workshops, Beijing, 1736–1760

Height: 4.55 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.66/1.40 cm

Stopper: gilt bronze, chased with a formalized floral design

Condition: minor natural surface wear, none of it obtrusive; otherwise, perfect. General relative condition: excellent, almost kiln condition

Provenance: Arthur Gadsby

Ian Wasserman

Hugh M. Moss Ltd., (circa 1972)

The Loch Awe Collection

Hugh Moss (HK) Ltd. (1985)

Published: Moss 1976, plate 39 (text pp. 62-63)

JICSBS, March 1979, p. 22, figs. 39 and 40

Kleiner 1987, no. 13

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, no. 17

Kleiner 1995, no. 27

Treasury 6, no. 1068, and front and back covers of one volume

Exhibited: Sydney L. Moss Ltd., London, October 1987

Creditanstalt, Vienna, May–June 1993

Hong Kong Museum of Art, March–June 1994

National Museum of Singapore, November 1994–February 1995

British Museum, London, June–October 1995

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, July–November 1997

Commentary: A distinctive feature of early-Qianlong painted enamels on glass is the relative thinness of the enamels and the painterly quality of the brushwork. Court artists, highly trained in the tradition of calligraphic brushwork that gave Chinese painting one of its most profound inner languages, were involved in drawing up the designs and sometimes in painting the enamels. Failing that, it was skilled enamellers trained in the same aesthetic and overseen by court artists who produced them from preparatory sketches. Artistically, these early, painterly enamels represent the apogee of glass enamelling during the Qing dynasty. In the early phase of the art form, from the late Kangxi until the 1750s or early 1760s, technical control of the enamels was still marginal, and all known examples exhibit some degree of pitting or discolouration of the enamels. This continued to be a problem with some colours into the second half of the Qianlong reign. Although far from obtrusive, here the green enamel in particular (a perennially problematic colour) is pitted, as is the blue in places, but it is otherwise remarkably well fired for the period.

This design is purely Chinese in its conception, without any hint of the Western influence that appears, not unnaturally, in some wares with European subjects that rely to a greater extent on the use of colour and chiaroscuro rather than line to create form. The flower heads drawn without lines here do not by that quality reflect Western influence, but rather the 'bodiless' style made famous by Yun Shouping (1633–1690), whose works would have been well known to any court artist a mere half century after the painter's death. Here, the blossoms are balanced against the other elements of the design featuring the elegant black lines of the calligrapher's brush, with well modulated, expressive strokes.

The reign marks on these early-Qianlong enamelled glass bottles are distinctive and intriguing; rather than being in bold relief, they are flush with the foot. This is in sharp contrast to the raised blue enamel marks of the mid- to late reign and, oddly, to the use of blue enamel on the bodies of the bottles themselves, which although seldom in high relief, does not give the impression of being flush with the surface. The discrepancy between the reaction of the blue enamel on the body of the work and on the mark suggests a difference between either the enamels or the firing conditions of the two. It may have something to do with the greater fluidity required for mark writing. Once enamels have been produced in a glassworks, they are kept in solid form. In preparation for use, the solid enamel is crushed and reduced to a fine, even powder that is then mixed with a liquid so that it forms a paint that can be brushed onto the surface to be enamelled. Depending upon the colour of enamel and desired effect, the liquid may vary, but Tang Ying identified three media in 1743 (cf. Treasury 6, Chronological List, fifth month, twenty second day):

The five-colour painting that imitates Western [techniques] is called yangcai [Western colours]. A skillful painting craftsman is selected and the various colours are mixed....The colours employed are the same as those used for fuolang se [=falang cai, perhaps referring to cloisonné enamelling]. They are mixed with three different kinds of medium, the first being yunxiang oil [rue oil?], the second being liquid glue, the third being water. The oil facilitates washes; glue facilitates daubing, water facilitates building up or filling in [surface irregularities].

Another oil medium mentioned in the archives is duoermen or duoermendina oil, for which the English term doermendina oil has been invented (see Treasury 6, Chronological List, 1728, seventh month, tenth day); it was apparently imported and is possibly identifiable as turpentine (Zhou Sizhong 2008, p. 152, n. 1).

In any case, it is possible that whichever medium facilitated brushwork fluency had a concomitant effect on the chemistry of the enamel, encouraging it to eat into the surface of the glass to a greater extent. Another factor contributing to the singularity of some early-Qianlong reign marks is that some of them appear to have been polished. This is one example, but the most obvious is Treasury 6, no. 1071. Perhaps this was done mainly to resolve problems of the roughness arising from burst bubbles during the firing (of which there were obviously many on Treasury 6, no. 1071). Whatever accounts for these distinctive marks, the phenomenon remains extremely useful in identifying early-Qianlong enamels on glass, as they have the distinctive appearance of being flush with the glass surface, or at least in very low relief, while late- Qianlong examples are in higher relief — as are the copies of both Ye Bengqi and his student Wang Xisan.

The design here contains the usual selection of auspicious symbolism. The peony stands for wealth; the asters (lanju) for the arrival of male (nan) children; the bird, a white-headed bulbul (baitouweng) and the peonies together call to mind the common desire for wealth to last till one's old age (fugui baitou); the composite design of a butterfly hovering over a flower signifies the affection between lovers; while the formalized lingzhi heads along the borders, resembling the heads of ruyi sceptres, imply wish fulfilment (ruyi). Two closely related bottles are in the J & J Collection (Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, nos. 187 and 188), and another, although perhaps a little later, is in the imperial collection, Beijing (Li Jiufang 2002 , no. 104).

宮廷的願望

半透明乳白色玻璃施琺瑯彩;平唇、平斂底、突出凸形圈足;通體繪一白頭翁棲於枝頭,有藍菊、含苞的牡丹枝,有蝴蝶棲息於一朵盛開之牡丹花上,頸、肩、近圈足處飾不同如意紋,肩部間加垂蕉葉紋,圈足外壁繪如頸部 "C" 形相背雲紋的簡化圖案; 底藍琺瑯彩書二行"乾隆年製"楷款

御製品,宮廷作坊作,北京,1736~1760

高:4.55 厘米

口經/唇經:0.66/1.40 厘米

蓋:描金青銅,雕鏤起花縟麗

狀態敘述:微不足道、不引人注目的磨擦,此外完善;一般相對的狀態:極善,幾乎出窯狀態

來源:Arthur Gadsby

Ian Wasserman

Hugh M. Moss, Ltd (約1972)

Loch Awe 珍藏 (作家瑪麗.斯圖爾特夫人)

Hugh Moss (HK), Ltd (1985)

文獻:Moss 1976, 插圖39(論述,頁62~63)

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1979年3月,頁22,圖39、40

Kleiner 1987, 編號13

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, 編號17

Kleiner 1995,編號27

Treasury 6,編號1068、第一封面、封底

展覽﹕Sydney L. Moss Ltd, 倫敦, 1987年10 月

Creditanstalt, 維也納, 1993年5月~6月

香港藝術館,1994年3 月~6月

National Museum of Singapore, 1994年11月~1995年1月

大英博物館, 倫敦, 1995年6月~10 月

Israel Museum, 耶路撒冷, 1997年7月~11月

說明:清初玻璃胎畫琺瑯的一個特點是琺瑯比較不濃,可以用中國傳統的繪畫技法來畫圖像。無論是內廷的畫家或設計師,都受過國畫技法的訓練,琺瑯廠的琺瑯師也一定有若干傳統工筆的本領。康熙晚年到1750年代或1760年代初,琺瑯匠對材料還沒有完善地掌握,那時期已知的玻璃胎琺瑯煙壺一律都呈一定程度的麻點或變色。某些色彩一直到乾隆後半期還有問題的。譬如,本壺的綠彩和部分的藍彩呈現麻點。這個現象並不引人注目,而且本壺是當期燒製得非常成功的一例,但還具當時使用琺瑯彩的特徵。

本壺圖案直接或間接師法惲壽平(1633~1690)的沒骨花卉,後加勾畫葉脈筋絡,精美可人,極具典雅明麗之氣韻。

這些乾隆早年的白料琺瑯彩煙壺的年款具有一個引人興趣的特點,它們和周圍的底是齊平的。乾隆中、後期的卻是凸起的。再看本壺底款以外的藍彩,好像也是稍微凸起的,要不是因為燒窯情況的不同,便可能是因為材料的差異。寫字和繪畫的要求不一樣,磨製琺瑯坯子的時候用不同的媒質材料是合乎情理的。 如唐英《陶冶圖說》說﹕"五彩繪畫仿西洋曰洋彩。選畫作高手,調合各種顏色......所用顏色,與琺瑯色同。調法有三﹕一用芸香油;一用膠水;一用清水。油便渲染,膠便搨刷,清水便堆填也"(桑行之1993,頁139)。還有所謂多爾門油或多爾門的那油,是"西洋人......燒琺瑯調色用"的, 或許就是松節油(周思中2008,頁152,注1)。且不說芸香油和多爾門油到底是甚麼媒質,我們推測,當時調合書年款用的琺瑯彩的媒質可能是燒窯時侵蝕玻璃面的,因而款識和周圍的底是齊平的。乾隆早期的年款還有另一個特色﹕有的好像是磨光的。本壺就是一個例子;Treasury 6,編號1071是更明顯的例子。也許磨光底款的目的是修補氣泡產生的麻點。無論如何,這些特點對鑒定玻璃胎畫琺瑯的乾隆早期作品應該很有用,應該有助於辨別乾隆晚期的玻璃胎畫琺瑯煙壺和葉仲三、王習三的仿造品。

與本壺可以聯系的有 J & J 珍藏的兩件(Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, 編號187、188);後來的有故宮珍藏中的一件(李久芳2002,編號104)。

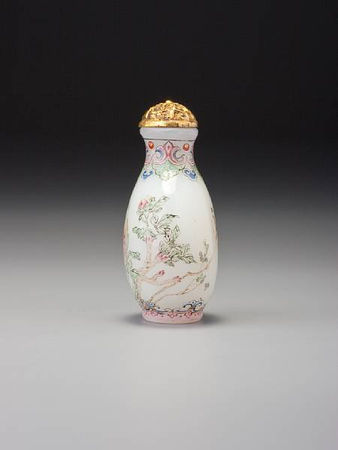

A 'famille-rose' porcelain moonflask 'landscape' snuff bottle. Attributed to Tang Ying, Imperial kilns, Jingdezhen, Qianlong iron-red seal mark and of the period, 1736–1756. 5.08cm high (original ivory stopper and spoon). Estimate: HK$1,400,000 - 2,000,000. Sold for HK$3,960,000; photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 6, no. 1149

瓷胎月琴山水鼻煙壺

推定為唐英作,景德鎮,鐵紅乾隆年款,1736~1756

Southern Moon-Flask

Famille rose enamels on colourless glaze on porcelain; with a convex lip and recessed flat foot surrounded by a protruding flattened footrim; the slightly convex circular panel on each main side painted with waterside landscape scenes, one a winter scene in which two scholars, one holding a walking staff, cross a bridge towards a house beneath pines, a view through the window revealing a volume of books set on a desk inside, with a distant open pavilion on the far bank of the river beyond, the other a spring scene in which a scholar, also with a walking staff, crosses a bridge towards a fenced dwelling beneath trees, with paddy fields in the distance; the panels surrounded by a diaper design of interlocking fylfots (wan symbols); the neck with a band of acanthus leaves; the foot inscribed in iron-red seal script Qianlong nian zhi (Made during the Qianlong period); the lip, inside of the neck, and footrim all painted gold; the interior glazed

Attributed to Tang Ying, imperial kilns, Jingdezhen, 1736–1756

Height: 5.08 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.70/1.09

Stoppers: ivory; original

Condition: perfect condition, very close to kiln condition, with only minor wear to some of the gold enamel on the narrow sides; even the gilding of foot and lip remains intact. General relative condition: outstanding. Original ivory stopper, cork, and spoon also perfect

Provenance: Robert Hall (1995)

Published: Hall 1995, no. 1

Robert Hall, business Christmas card, 1995

JICSBS, Winter 1995, p. 1

Robert Hall, business brochure, undated

Sin, Hui, and Kwong 1996, no. 95

Treasury 6, no. 1149

JICSBS, Spring 2009, p. 9, fig. 9

Exhibited: The Tsui Museum of Art, Hong Kong, October 1996

Commentary

It was once generally believed that the production of porcelain snuff bottles did not begin significantly until the second half of the Qianlong period. Early-Qianlong enamelled porcelain snuff bottles were extremely rare and, until very recently, few of them had been published. However, with the recent publication of several early bottles associated with Tang Ying, who directed the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen during the early Qianlong period, and recent access to the imperial Archives concerning the manufacture of works of art, we now have a clearer picture of porcelain snuff-bottle production.

This bottle is part of a series of the same form and colour scheme but with different landscape panels, each with one or more scholars in evidence. Six are known in addition to this one, and another in the Bloch Collection (Treasury 6, no. 1148), making eight in all. They are published in Geng Baochang and Zhao Binghua 1992, no. 137 (also in JICSBS, Spring 2006, p. 4, fig. 3); Lam 2003, p. 8, figs. 3a-c; Sotheby's, New York, 23 March 1998, lot 79, (also in JICSBS, Autumn 1998, p. 24, fig. 2, a pair now in the Crane Collection); and a pair in Drouot, Millon-Jutheau, Paris, 2 February 1983.

From the condition of the ivory spoons, the silk binding of the cork, and the enamels, it is obvious that the Bloch examples were barely used before becoming treasured collector's items, and they probably resided in the imperial collection for some long time before leaking onto the market, most likely between 1860 and 1924. The fact that the delicate original stoppers, ivory spoons, and integral corks (wrapped around with imperial yellow silk to provide a tight fit) have survived is another indication that the bottles are probably from the imperial collection and were not distributed by the court t the time.

We know from the records that the emperor instructed Tang Ying not to make stoppers for the fifty porcelain snuff bottles he required each year (see Chronological List in Treasury 6, for 1744, third month, sixteenth day). Thus, Tang Ying bottles from the early Qianlong reign were stoppered only after they arrived at the court; even though several, including the Bloch examples, have what appear to be original stoppers, none of the surviving examples has porcelain stoppers. Another of Tang Ying's likely products (in the Philadelphia Museum of Art Collection) has a similar, original ivory stopper. It is part of another series of bottles with poems and seals mentioned under Treasury 6, no. 1150. This suggests that what we see here was a standard type. We have in the past referred to this type of stopper as an 'official's-hat' stopper, but here it can be seen to resemble the emperor's more elaborate formal hats, a far more likely source of inspiration on imperial snuff bottles. An extraordinary original stopper on a unique Yongzheng enamelled-metal snuff bottle in the Marakovic Collection (China Guardian, 21 October 1996, lot 1879; also JICSBS, Spring 2004, front cover, centre) is based on the emperor's hat, complete with a real pearl finial. It is, no doubt, an early and more realistic prototype of the standard later form with its simplified, smaller finial and integral collar. The ivory version which appears on some Tang Ying bottles, including this one, are of the earlier type, with their more prominent finials.

To what extent these bottles were made as a set, or as significant groups of two, four, six, eight, or however many, is not clear. Although the scenes here may have been intended to represent the four seasons, the only apparent connection between the sixteen different scenes on the eight known bottles is the predominance of scholars in landscape.

The construction of these bottles is interesting and may throw some light on the early range of bottles supervised by Tang Ying. They are constructed in the standard Qing-dynasty way of making a moon flask, by luting two moulded halves together vertically along the narrow sides. (The earlier, Ming method for moon flasks — snuff bottles did not exist then — was to lute two sections horizontally). The bulging strip of slip porcelain that was used to lute them together remains clearly visible on the inside, although the outside has been smoothed off to conceal the join. In this case, however, a rare departure for the snuff-bottle world is seen in the treatment of the foot, made separately and luted onto an oval hole left in the original two-part mould for the main body. This leaves an oval recession inside where the hollow foot is affixed to the body. This distinctive feature is also found on Treasury 6, no. 1150, also attributed to Tang Ying's supervision, and on all of the other early bottles likely to have been made under his watchful eye that we have been able to handle so far.

The formal quality of this group of early-Qianlong porcelain snuff bottles and the standard of the painting and enamelling are extraordinary. The scenes are each individually composed and exquisitely painted. Since its identification, this early group of imperial porcelain snuff bottles has been widely admired and has appropriately drawn a great deal of attention from collectors. They are far harder to find than imperial enamels on metal produced at the palace workshops contemporaneously, and they are as rare as palace enamelled glass bottles of the early Qianlong period, perhaps even rarer.

The involvement of Tang Ying personally in this series of bottles is discussed under Treasury 6, no. 1150, and is also the subject of an article: Moss 2009. Although we have left open the possibility of this group of bottles dating from later in Tang's career, they may well date from as early as the 1740s.

江南夏秋景月琴形煙壺

瓷胎,無色釉上施粉彩;凸面唇、平斂足、突出平底圈足;腹兩面雷紋開光彩繪江南山水,其一為溪橋上二人向松下書屋走來的雪景,其一為溪畔野屋,一人策杖行橋上的春景,兩側繪金彩卍字變紋,頸部有金彩蕉葉紋;底礬紅書"乾隆年製"四字篆款;唇、頸內、圈足皆描金,壺內亦施釉

推定為唐英作,景德鎮官窯,1736~1756

高:5.085 厘米

口經/唇經:0.70/1.09 厘米

蓋:象牙;原件

狀態敘述:完善;近乎出窯狀態,只有兩側金彩稍微磨損,連口沿和圈足描金保留得很完好;一般相對的狀態:優秀;原配蓋、塞、匙皆完善

來源:羅伯特.霍爾 (1995)

文獻:Robert Hall 1995, 編號1

羅伯特.霍爾, 商務聖誕卡, 1995年

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society 1995冬期,頁1

羅伯特.霍爾, 商務冊子,未注明年月日

冼祖謙、許建勳、鄺溥銘 1996,編號 95

Treasury 6, 編號 1149

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society 2009春期,頁9,圖9

展覽:徐氏藝術館,香港,1996年10 月17日~11月15日

說明:以前,很多人認同陶瓷鼻煙壺到了乾隆時期後半才有值得主意的產量。早期的陶瓷鼻煙壺並不多,文獻中所見的更少。而最近發表了幾件可以跟唐英聯繫的煙壺,清朝有關工藝品出產的檔案也陸續發表了,這都有助於理解陶瓷鼻煙壺的出產情況。

本壺以山水中的文人逸士為開光畫題,以此形式和色彩設計相同者,已知的有七件,包括伯樂珍藏還有一件,Treasury 6編號1148。也有耿寶昌、趙炳驊,《中國鼻煙壺珍賞》, 編號137 (亦發表於《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 2006春期,頁4,圖3);林業强 2003, 頁8,圖3a~3c;蘇富比,紐約,1998年3 月23日,拍賣品號79(亦發表於《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1998秋期,頁24,圖2,兩件,今為Crane 珍藏所收); 和Druout, Millon-Jutheau, 巴黎,1983年2月2日,兩件。

看伯樂珍藏編號1148、1149兩件的牙匙、裹塞絲綢、琺瑯等的狀況,它們明顯是幾乎沒有人用過就當成珍貴的收藏品物,大概一直到大約1860至1924年間偷偷摸摸地來到市場的時候都安放在紫禁城珍藏中。因為易碎的蓋、牙匙、以黃色絲綢裹得能塞緊的塞都保存下來,我們能推定這兩件煙壺從未頒賜過,製成以後都留在皇家珍藏中。

《造辦處各作成做活計檔案》載:"乾隆九年三月十六日,唐英將造燒的洋彩錦上添花各式鼻煙壺四十件,持進交太監胡世傑進呈,奉旨:嗣後鼻煙壺每年只燒五十,著其中不要大了,亦不要小了,其鼻煙壺蓋不必燒來"(張榮2008,頁13引)。據此知道乾隆早期的瓷煙壺到了北京以後才安裝蓋,雖然本壺和其他的幾件都帶原件的蓋,果然沒有一件是瓷製的。費城藝術博物館藏的一件可推定為唐英指揮下作的煙壺帶有類似的原件牙蓋, 好像這是一種標準型式。(費城的煙壺屬於一系列題詩帶款的煙壺,請參閱Treasury 6, 編號 1150下的論述。)我們以前把這種蓋叫做"官帽蓋",但是本件也許更像皇帝的朝冠,非賜品的宮廷用器帶樣式比較壯偉的蓋,也是合乎情理的。Marakovic珍藏中有帶特殊原件蓋的雍正銅胎琺瑯彩煙壺(中國嘉德國際拍賣有限公司,1996年10月21日,拍賣品號1879; 《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 2004春期,封面),那件蓋以皇帝的冠冕為模型,連珍珠頂都有。它無疑是早期而比較逼真的原型,後來的尖頂飾是簡化的、較小。本壺和其他一些唐英作的煙壺所帶頂飾較突出的蓋則是早期的式樣。

這些煙壺是不是一套或幾套的,一套有多少煙壺,是不是每套是二件壺上繪製四季圖景的,都不清楚。我們只能說,大多數的圖象都描繪著文人雅士的幽隱情趣。

這系列煙壺的工藝很有意思,也有助理解早期的唐窯。用的是清朝典型的月琴形煙壺製作法,即把以模子成型的前後兩塊坯子拼接。(明代月琴形器的製作法是把成型的上下兩塊拼接,當時這種煙壺並不存在,且不討論。)壺內側壁可見有一帶粘接的瓷漿。背離煙壺工藝常規的是足的處理。足是另一部件,底部留了一個洞,足就被黏上去了,壺內足體黏合的地方有椰圓形的凹痕。上舉Treasury 6, 編號 1150以及到現在為止能夠查驗所有的早期唐窯也都具有同樣的凹痕。

這系列乾隆早期的瓷鼻煙壺形式奇妙,繪圖和繪彩上都達到了特別高的水平。圖象的構圖富於變化,筆法精工,這系列煙壺被認定以後,一直受到了廣泛的贊賞,當然也為收藏家注視。它們比同時期作的金屬畫琺瑯鼻煙壺還難得一見,跟乾隆早期的玻璃畫琺瑯煙壺一樣稀罕,抑或更罕見。

關於唐英躬自指揮和參入這系列琺瑯煙壺的燒造事宜,可參閱Treasury 6 編號1150的論述和 Moss 2009。 這系列煙壺可能是唐窯後期的製品,但也可能是乾隆4年到14年那麼早的製品。

A double-overlay sapphire-blue and white glass 'dragon' snuff bottle. Attributed to the Imperial glassworks, Beijing, 1760–1790

6.82cm high. Sold for HK$672,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 5, no. 1001

重疊套料龍鼻煙壺

推定為御用玻璃作坊製,北京,1760~1790

Star-Tailed Dragon

Translucent milky white, transparent sapphire-blue, and translucent white glass; with a flat lip and recessed convex foot surrounded by a protruding flat footrim; carved as a double overlay with a continuous design of two four-clawed dragons, one amidst formalized clouds, the other rising from formalized waves

Attributed to the imperial glassworks, Beijing, 1760–1790

Height: 6.82 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.70/1.42 cm

Stopper: ivory; gilt-bronze collar

Condition: exposed bubble at the outer lip filled with dirt resembles a chip, but is not; it is part of the original process, although the dirt has accumulated later; tiny pale 'stone' (an impurity left as an inclusion in the glass of the original batch) towards the end of the dragon's tail appears a paler, beige colour; again, part of the original process; probable minor recutting of the edges of upper cloud formations: not obtrusive; minor abrasions to the flat footrim from use. General relative condition: extremely good

Provenance: Robert Kleiner (1991)

Published: JICSBS, Winter 1992, front cover

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, no. 120

Treasury 5, no. 1001, and front and back covers of one volume

Exhibited: Hong Kong Museum of Art, March-June 1994

National Museum, Singapore, November 1994-February 1995

Commentary: This bottle is technically one of the finest and artistically one of the most spectacular known pieces of later Chinese glass. Comparing it with Treasury 5, nos. 1002 and 1003 where three different colours are contrasted, demonstrates the refinement of producing an essentially straightforward double overlay not only with two colours the same, but a visually undemanding white. Combined with an attractive form, magnificent design, masterly balance of lines between the upper and middle planes of colour, and breathtaking command of the medium, it is revealed as a transcendent masterpiece. Some earlier bottles display finer detail and more perfect finish (the ground plane here undulates very slightly, but not enough to disturb the eye), but nothing is endowed with more striking power in the combination of visual impact, artistic quality, and technical control. On an 'Ooomph' scale of one to ten, this is an emphatic, unquestionable, unanimous ten (and we briefly considered eleven).

We discussed under Treasury 5, no. 940 its relationship to a group of dragon carvings which we believe spans the late Qianlong period and extends into the nineteenth century, where the characteristics of the group were examined. That example bears a cyclical date that corresponds to 1780. We believe this to be an imperial product, for if it is not, there seems little point in the Qianlong emperor having his own workshops, to which he could co-opt all the best carvers. Another example, related to this bottle, in white with a red middle plane and a white ground, has the plantain neck of Treasury 5, nos. 1002-1004 (China Guardian, Beijing, 21 April 1999, lot 1100) and a dragon clearly related to this one, while the plantain neck and lesser quality link it to the others. A useful clue is provided by its five-clawed dragon since at that time such beasts were the exclusive prerogative of the imperial family. We noted under Treasury 5, no. 940 that the entire group, including this example, was linked through a series of poems in seal script to a group of other likely imperial wares, including the bannerman bottles discussed under Treasury 5, no. 893. We also noted that dragons, some with five claws, were a mainstay of the group. At the same time, however, it was common practice for the court to produce four-clawed dragon decoration on works of art for distribution to the ennobled. The early nineteenth-century decline in palace arts, including carving, is widely acknowledged, documented, and evident in other wares. Thus, in view of the comparisons we can make with this collection, and the extraordinary quality of this bottle, we believe that it must be from around the same time as Treasury 5, no. 940—give or take a decade. As a work of art it fits comfortably into the late Qianlong period. The extraordinary quality of this example, surpassing even that of the dated one, further suggests that this probably preceded it, hence our dating. The footrim is deep, very crisp, and sharp-edged, being as confident as any carved, and the line at the meeting of the white rim and the blue of the foot is admirably controlled, all constituting further indication of an eighteenth-century date. The only hint of a late eighteenth-century date here might be the fact that the middle of the foot fades to the paler under-colour, but it does so very evenly in contrast to the irregular bleeding exhibited by so many nineteenth-century glass bottles.

The motif of the dragon and clouds, signifying vast good fortune, is discussed under Treasury 5, no. 978. The standard design of a large dragon in the sky, above a smaller one emerging from the waves, illustrates the saying: 'The hoary dragon teaching its young' (canglong jiaozi), an allusion to the loving guidance a father would give to his son.

Were practically every group of overlay bottles not related to every other, we would have given names to some of the core groups. This was to have been described as made by the 'Star-tailed Dragon Master.' A problem arising from any such effort is that we are not sure to what extent the master is the designer or the carver. In the imperial workshops of the Qianlong emperor there were doubtless carvers who, given the incentive, could produce a masterpiece of this sort, and the artistic personality may reside more in the artist who drew up the design than in any individual carver.

海星攀龍尾

通體乳白色半透明玻璃 ,套飾寶藍、白色透明料;平唇、斂凸底、平底圈足;二層料雕二條四爪龍,一條踩雲紋而行,一條由浪濤紋升

推定為御用玻璃作坊製,北京,1760~1790

高:6.82 厘米

口經/唇經:0.70/1.42厘米

蓋:象牙,描金青銅座

狀態敘述:唇沿有似積聚灰塵的缺口,其實是原有的氣泡,灰塵當然是後來的;雲龍尾巴上淡色的雜質也是玻璃原有的;雲紋上部可能有再刻的小小痕跡,不引人注目;因為曾有人享用這件煙壺,圈足上有微不足道的磨損;一般相對的狀況:極善

來源:Robert Kleiner (1991)

文獻:《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society 1992 冬期,封面

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, 編號120

Treasury 5, 編號 1001 與第三冊封面與封底

展覽:香港藝術館,1994年3 月至6月

National Museum of Singapore, 1994年11月至1995年2 月

說明:在技術和藝術兩方面上,本壺是中國晚期玻璃器的傑作之一。跟套飾三色料的煙壺相比,這個相配寶藍和鉛白色的套料優雅多了。形式悅目,圖案壯麗,上下二層料的平衡局勢得手,技術掌握驚人,玻璃匠的功力實在不凡。若干早一點的玻璃套料鼻煙壺更體貼入微,更完備(本壺通體面稍微起伏,但並不觸目),可是在視覺作用、美術價值、技術把握各方面本壺是獨出新栽的。這煙壺絕對是頂級之作。

Treasury 5編號940 是庚子(1780)年製的套料煙壺,一面上雕呈的四爪雲龍像本壺的雲行龍一樣,細長的尾巴終端有五腕海星形的附屬物。我們認為那個煙壺是朝廷玻璃廠的產品。有另一個與本壺和本壺的龍有關的白地,紅、白二色套料的煙壺,可是它像Treasury 5編號1002~1004一樣,唇緣下雕呈芭蕉葉紋(中國嘉德國際拍賣有限公司,北京,1999年4月21日,拍賣品號1100),品質也不如本壺好。且看本壺五爪龍,根據清代官袍文飾的規定來推測,帶五爪龍的煙不是皇上或皇太子親用,只有官民因有功而奉上特賜才能得到這類煙壺。在清後期會有人忽略王朝這類規矩,不過,因為本壺品質高,不呈示朝廷工藝從十九世紀初開始的衰退,我們認定它跟上舉Treasury 5編號940那壺是同時作的,至多相差十年。視之為乾隆晚期的物品最合適。圈足深,雕得乾淨利落,白色的圈足和藍足的交接線很穩妥,這也都是十八世紀的特徵。足的寶藍色從邊緣到中心逐漸變淡,這會表明本壺是十八世紀後期的產物,但值得注意的是,這個現象並不像十九世紀玻璃煙壺常見的不整齊的滲色。

本壺的圖案就是"帶子上潮(朝)"或是"蒼龍教子",兩者寓含的意思大同小異。

An inside-painted rock-crystal snuff bottle. Gan Xuanwen, Lingnan, 1810–1825, sold with accompanying watercolour by Peter Suart, 5.6cm high. Sold for HK$336,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 4, no. 452

水晶內畫內書鼻煙壺

甘烜文,嶺南,1810~1825

Fragrant Sleeves

Crystal, ink, and watercolours; with a concave lip and slightly recessed convex foot surrounded by a protruding flat footrim; painted on one main side with a river landscape scene with a scholar strolling across a plank bridge from a country retreat, a sailboat and further buildings in the distance with mountains beyond, the upper left-hand corner inscribed with the signature, Xuan, and one illegible seal of the artist; and on the other main side with a poetic inscription in a writing style combining elements from the regular and clerical scripts with one token, and another seal of the artist, Gan

Gan Xuanwen, Lingnan, 1810–1825

Height: 5.6 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.58/1.55 cm

Stopper: coral; gilt-bronze collar

Condition: Material: some icy flaws, two of which on one narrow-side facet at the edge are possibly small bruises. Bottle: miniscule chip on inner lip; barely noticeable. Painting: Minor snuff staining but otherwise in remarkable condition

Illustration: watercolour by Peter Suart

Provenance: Hugh M. Moss Ltd. (1979)

The Belfort Collection (1986)

Published: JICSBS, December 1974, p.15, figs. 13 and 14

Jutheau 1980, p. 69, fig.1

JICSBS, Spring 1991, p.19, figs. 44 and 45

Kleiner 1995, no. 371

Treasury 4, no. 452

Exhibited:

British Museum, London, June–October 1995

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, July–November 1997

Christie's, London, 1999

Commentary: As we mentioned under Treasury 4, no. 451, Gan Xuanwen appears to have received a regular supply of crystal bottles and does not appear to have painted in glass at all. This is one of the more popular forms, with the rectangular shape set with a cylindrical neck and panels raised on all four sides. Variations on this shape were used frequently. Another popular form, although less common, was a hexagonal faceted bottle with a cylindrical neck (see Treasury 4, no. 455). The regular supply of a particular shape of bottle, or series of shapes, suggests that Gan had a local crystal carver who could do his bidding, perhaps a carver from Guangzhou, which was a major centre for the production of a wide range of arts and crafts during the Qing dynasty. If the supply was from a distant workshop it seems less likely that it would remain so consistent throughout his career (but see discussion under Treasury 4, no. 456 for an exception).

This lovely little painting is in the standard 'good' condition for an early Lingnan work even though the original colours have turned brownish through long contact with snuff, rendering the entire scene rather sepia in tone, the lines and washes are not scratched or otherwise worn. It is a rather similar process, although through a different agent, to the gradual browning of the ancient paper or silk of a painting. If we could see Song-dynasty paintings in their original state we would be quite surprised after all these years of gazing at them through a patina of gathering darkness. It is possible to see what the original colours were here, and we have as a guide the extraordinary condition of Treasury 4, nos. 450 and 451 to give us some idea of the studio appearance of a bottle like this. Another that has survived reasonably intact is Treasury 4, no. 457, but as a rule, the colours have become subdued by snuff over the years.

The poem reads:

[The bottle is] white as snow and clear all around.

The aroma kept in it is long-lasting.

Working on it between one's fingers and palms,

[Even] the sleeves are tainted with that wonderful fragrance.

This is again likely to be a poem by Gan himself, or one of his friends (see discussion under Treasury 4, no. 451). Snuff-taking in early nineteenth-century China was at its height, the bottles were collected and produced as art and the contents were considered to be beneficial to health, both mental and physical, thus making it an appropriate, and in the case of Gan and Yiru jushi, a popular subject for inscriptions. A possible indication that the poem was not written for this particular bottle is to be found in the description of the bottle as being 'white as snow' where the bottle is obviously colourless, but it is far more likely that this is an indication not to take Chinese poetic sources too literally, unless it refers to the roughened interior surface of the bottle to allow the colours better purchase, which gives it a frosted appearance. However, if a crystal bottle can be compared to jade (see Treasury 4, no. 450), it can certainly be described as 'white as snow' without too much stretch of an artistic imagination.

The use of the abbreviated signature, just using the first character of his given name, is unusual but not unique. When using his proper name, or at least the one that includes his family name and the name by which we know him today, he sometimes wrote it in full, sometimes used just the given name, and occasionally just the first character of the given name, as here. He also signed bottles leaving off the second character of his given name, i.e., Gan Xuan, which caused the initial confusion as to whether his name was Gan Xuan or Gan Xuanwen, a problem long since resolved in favour of the latter.

滿袖奇香

水晶、墨、水色;微凹唇、微斂凸底、突出平底圈足;一面內畫山水,上繪"烜"一款,款下繪白文一印,模糊不清;另一面內題一首絕句詩:"白雪方圓潔,壺天道味長。經營耕指掌,滿袖拂奇香",其後繪白文"甘"一印

甘烜文,嶺南,1810~1825

高:5.6 厘米

口經/唇經:0.58/1.55 厘米

蓋:珊瑚,描金銅座

狀態敘述:水晶:結冰似的瑕疵,一側沿稜的二瑕或許為撞擊痕;壺:唇內沿有微乎其微的缺口,很難辨出;內畫:呈鼻煙的隱微染色,但意外地良好

有彼德小話 (Peter Suart) 水彩畫

來源:Hugh M. Moss Ltd, 1979年

Belfort 珍藏,1986年

文獻:《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1974年12月、頁15 ,圖13、14

Jutheau 1980, 頁69, 圖1

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1991年春期、頁19 ,圖44、45

Kleiner 1995, 編號371

Treasury 4, 編號452

展覽:大英博物館, 1995年6月至11月

Israel Museum, 耶路撒冷, 1997年7 月至11月

佳士得,倫敦,1999年

說明:看來,甘烜文繪畫的水晶煙壺的供應正常,卻從來沒畫過玻璃壺。本壺的形式是其中比較多見的:身為長方體,帶圓筒形的頸,四面為凸起的平板。這種形式的變種最普遍;六角形的也是常常見到的。有這種形式水晶煙壺的供應正常,大概是嶺南的水晶作坊給甘烜文提供的,或許是清朝重要工藝中心之一的廣州的水晶作坊。如果是離廣州比較遠的材料供應者,形式長期一貫的可能性較小。(Treasury 4, 編號456 是甘烜文內畫煙壺中形式上的獨一無二的例外。)

本壺內畫的狀況在早期嶺南作品當中來說還算是好的,雖然原色因與煙粉之長久接觸而變黃了,圖中的線條和淡水彩都沒因此而磨損。煙粉隱微染色的效果有如舊畫質地變黃變暗。題詩首句云"白雲方圓潔",顯然是指壺內壁細細的潔白沙面。參看 Treasury 4, 編號450、451,兩件甘烜文出坊狀態的內畫鼻煙壺,可以了解到 "白雲方圓潔" 的韻味。

本壺落款只有一個"烜"字,難怪有人以為這位內畫家有單字名。甘烜文畫的內畫鼻煙壺落款時曰"甘烜文",時曰"烜文",時曰"烜",時曰"甘烜",頗令人困惑的。(提到甘烜文的論文也經常把"烜"寫成"桓",此乃彼此傳抄、以訛傳訛的實例。)

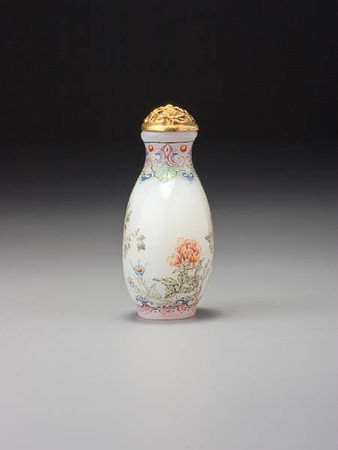

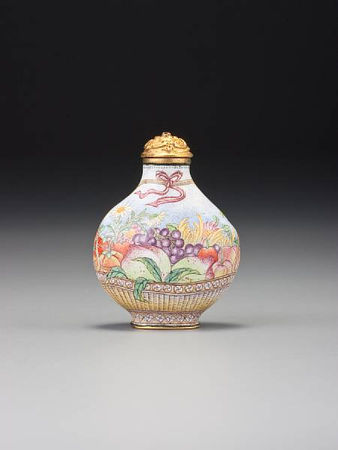

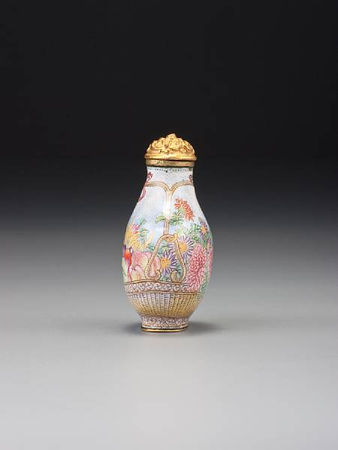

A Beijing enamel 'basket of flowers' snuff bottle. Imperial, palace workshops, Qianlong blue-enamel mark and of the period, 1736–1770, sold with accompanying watercolour by Peter Suart. 4.22cm high. Estimate: HK$1,800,000 - 3,000,000. Sold for HK$2,640,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 6, no. 1079

銅胎粉彩籃花鼻煙壺

御製品,宮廷作坊,乾隆年藍楷款, 1736~1770

Basket of Abundance

Famille rose enamels on copper, with gold; with a flat lip and slightly recessed, slightly concave foot surrounded by a protruding flat footrim; painted to simulate a basket of flowers, the base of the bottle acting as the woven basket, its upper edge with a band of fylfots (wan symbols) enclosed in circles and the foot of the basket with a diaper pattern of the same motif, the two basket handles on the narrow sides with a separate carrying handle hooked into them, dividing at the shoulders to encircle the neck, each with a tied ribbon on the main side, the basket filled with two peaches growing from an unseen branch, the leaves of which are visible, a bunch of grapes, two Buddha's hand citrons, two plums, a persimmon, and other fruit, with chrysanthemums and daisies, the upper body with a blue-stippled white ground representing the sky; the foot inscribed in blue regular script Qianlong nian zhi (Made during the Qianlong period); the interior covered with a patchy, turquoise-blue enamel; the exposed metal gilt

Imperial, palace workshops, Beijing, 1736–1770

Height: 4.22 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.68/1.19 cm

Stopper: gilt bronze; chased with a formalized floral design

Condition: perfect; minor surface scratches and abrasions visible only under magnification. General relative condition: unusually excellent; even the original gilding is largely intact, with only minor wear

Illustration: watercolour by Peter Suart

Provenance: Martin Schoen

Paul and Helen Bernat

Sotheby's, Hong Kong, 15 November 1988, lot 79

Published:

Moss 1976, plate 27

Arts of Asia, September-October 1990, p. 96

JICSBS, Winter 1992, front cover

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, no. 5

Kleiner 1995, no. 8

Treasury 6, no. 1079

Exhibited: Hong Kong Museum of Art, March–June 1994

National Museum of Singapore, November 1994–February 1995

British Museum, London, June–October 1995

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, July–November 1997

Commentary: The subject of a basket of flowers or fruit, or both, was a popular one at the palace workshops during the eighteenth century. It appears on glass snuff bottles that can be attributed to the court starting from the early Qianlong period at the latest (see Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, no. 362, where no. 395 is a spectacular late-Qianlong, double overlay with begonias in a basket). It was also a popular design on the Guyue xuan group of enamelled glass wares from the second half of the Qianlong reign, represented in the Bloch Collection by Treasury 6, no. 1105. Others may be found in the J & J Collection, Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, no. 200; Kleiner 1990, no. 51 (decorated with two baskets, one with the emblems of the Eight Immortals, one with flowers); Chinese Snuff Bottles 6, no. E.7, and JICSBS, Spring 2004, back cover, lower-left, the spectacular example from the Marakovic Collection. Although the design was popular in the Qianlong period, it can be traced back to palace enamelling of the Kangxi reign. One of the enamelled porcelains bowls with floral decoration bearing the mark Kangxi yuzhi (Made by imperial command of the Kangxi emperor) has a group of auspicious flowers contained within a 'basket' of lotus petals, the foot of the bowl painted as a cylindrical segment of the upper stem (Guoli Gugong bowuyuan 1967a, plate 8). It would have been a small leap of the imagination to evolve this design into the popular baskets of flowers of the Qianlong period. The popularity of the subject probably arises from one likely symbolic reading of the basket (lanzi) that may suggest male children (nanzi), one of the three desires dear to the Chinese heart that are embodied in the term Sanduo (Three plenties). These are, Duofu (Plenty of happiness), Duoshou (Plenty of years to live) and Duonanzi (Plenty of male children). The concept can be traced back to the 'Heaven and Earth' chapter in the Zhuangzi, compiled during the Warring States period. The 'Three plenties' or 'Three abundances' are also represented by the Buddha's hand citron, peach, and pomegranate, two of which appear in the basket here. The pomegranate may have been considered superfluous given the similar symbolic meaning of the basket itself, or the inclusion of grapes, which are also a symbol of ample progeny. Longevity is represented by the peach.

It seems technically preferable to enamel both the inner and outer surfaces of any form when painting with enamels on metal. This helps equalize the tensions between the brittle, glassy enamel surface and the metal ground, and with one or two rare exceptions (significantly, experimental wares from early Guangzhou production, such as Treasury 6, no. 1124), enamelled snuff bottles have a coating of enamel inside. Decoratively this is meaningless, since it is all but invisible, even without any snuff in the bottle. Functionally, it could have done little to maintain the qualities of the snuff, since in most cases the interior enamelling is sufficiently patchy that significant areas of metal are left exposed. Covering the interior surface of a snuff bottle with enamel was obviously rather difficult, more difficult than glazing the interior of a larger vessel, and the fact that even flat panels intended to be inserted in furniture or other objects, where their backs would never be seen, are similarly enamelled suggests that it can only have been a technical requirement. Although there are exceptions, as there always are to those 'rules of thumb' in which beginners delight and that experts try to avoid, there is one that may prove a useful, even if not infallible guide to origin: it seems that the majority of eighteenth century Beijing enamel snuff bottles were painted inside with turquoise enamel, while white was used on their Guangzhou counterparts. The occasional late-Qianlong Beijing enamel may flout the rule, as does Treasury 6, no. 1107, but it is a useful one nonetheless.

一籃豐盛

銅上施琺瑯彩與金彩;平唇、微斂微凹底、平底圈足;彩繪一籃花,腹下部則彩繪籃,以中飾卍字的圈子飾籃邊,以中飾卍字的菱形花紋飾圈足外壁,兩側彩繪的籃提手都掛在另一件勾形物上,該物在肩上分成兩條而圍繞肩部,就在正面中間繫蝴蝶結,籃中放桃子、葡萄、佛手、菊花等吉祥物,腹上部白地點畫藍點彩,底有"乾隆年製"四字藍楷款,內壁不均地塗綠松色琺瑯彩;露出的紅銅描金

御製品,宮廷作坊, 1736~1770

高:4.22 厘米

口經/唇經:0.68/1.19 厘米

蓋:描金青銅,鏤刻形式化的花朵

狀態敘述:完善;微乎其微的的抓痕和磨擦,只有放大才看得見;一般相對的狀態:例外良善;連原來的描金也呈現極少的磨耗。

有彼德小話 (Peter Suart) 水彩畫

來源: Martin Shoen

Paul and Helen Bernat

蘇福比,香港,1988年11月15日,拍賣品號79

文獻:Moss 1976, 插圖27

Arts of Asia, 1990年9 月~10月,頁96

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1992年冬期,封面

Kleiner, Yang, and Shangraw 1994, 編號5

Kleiner 1995, 編號8

Treasury 6, 編號1079

展覽﹕香港藝術館,1994年3 月~6 月

National Museum of Singapore, 1994年11月~1995年1月

大英博物館, 倫敦, 1995年6月~10 月

Israel Museum, 耶路撒冷, 1997年7~月11月

說明:十八世紀中,籃花、籃水果的圖形是宮廷作坊吃香的內容。最晚推定作為乾隆初的玻璃煙壺就有之(Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, 編號362;同書編號395為乾隆晚期奪目的二層套料籃花煙壺)。乾隆後半期的古月軒玻璃胎畫琺瑯器也常見這類圖形, 如Treasury 6 編號1105;Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, 編號200;Kleiner 1990, 編號51 ;Chinese Snuff Bottles 6, 頁105,編號E.7;《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 200401 春期,封底左下,Marakovic 珍藏的奪目煙壺之一。這個圖形可以追溯到康熙的宮廷作坊琺瑯畫,參照國立故宮博物院1967a,插圖8的"康熙御製"碗,所畫盛放吉祥花朵的蓮瓣"籃"很容易會進展成乾隆期的花籃。

從技術方面來看,金屬胎的琺瑯器還是內壁塗琺瑯好,有助於使易碎的琺瑯面和金屬地的張力相等。除了寥寥幾件的琺瑯煙壺(如廣州早期的試驗器)以外,所有的琺瑯鼻煙壺都是內壁塗琺瑯的。從修飾方面來看,器內的琺瑯當然沒有意義,就是壺裏沒有鼻煙也看不見。從保護鼻煙質量方面來看,也不濟於事﹕小小的煙壺內塗琺瑯,顯然不順手,一般都斑駁不均。借鑒家具畫琺瑯的鑲板雖然板背永不露出但還是塗琺瑯的,我們可以推斷這樣作是技術要求。一種概測法是﹕十八世紀的琺瑯煙壺內壁塗綠松色的北京作的,塗白色的是廣州作的。當然,這並非放之四海而皆準; Treasury 6,編號1107的乾隆晚期北京琺瑯煙壺就是一個例外。

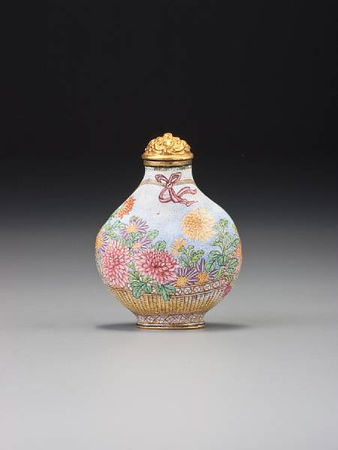

A Beijing enamel 'millefleurs' snuff bottle. Imperial, palace workshops, Qianlong blue-enamel mark and of the period, 1736–1770, 5.27cm high. Sold for HK$4,200,000. photo Bonhams

Footnote: Treasury 6, no. 1081

銅胎畫琺瑯百花鼻煙壺

御製品,宮廷作坊,藍乾隆年款,1736~1770

Floral Abundance

Famille rose enamels on copper, with gold; with a flat lip and concave foot surrounded by a barely protruding flat footrim; painted with a continuous millefleurs design including peonies, camellias, pear blossom, convolvulus, chrysanthemums, orchids, hydrangeas, irises, hibiscus, asters, and lilies, some with leaves, the neck with formalized floral designs, with another around the base; the foot inscribed in blue regular script Qianlong nian zhi (Made during the Qianlong period); the interior covered with an extremely patchy, misfired, turquoise-blue enamel, the exposed metal gilt

Imperial, palace workshops, Beijing, 1736–1770

Height: 5.27 cm

Mouth/lip: 0.80/1.25 cm

Stopper: gilt bronze, chased with a formalized floral design; probably original

Condition: one patch of restoration about 1 cm at its broadest extent, on the main side with the central pale greenish-white and ruby red peonies—when facing the red peony, it is below it to the right; another smaller patch of restoration low on one narrow side a little below the central yellow bloom (0.9 cm at its widest point); some scratches on the base, and with tiny, invisible scratches and abrasions from use; gilding in unusually good condition, and overall appearance excellent

Provenance: Martin Schoen

Belle Schoen

White Wings Collection (1993)

Published: Perry 1960, p. 145, fig 154

JICSBS, Winter 1993, p. 10, fig. 10

Kleiner 1994a, plate 3, lower-right

JICSBS, Summer 1995, p. 35, no. 2

Kleiner 1995, no. 9, and dust-jacket

Kleiner 1997, no. 2

Curtis 1999, p. 79, fig. 6

Treasury 6, no. 1081

Exhibited: British Museum, London, June–October 1995

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, July–November 1997

Commentary: Flowers have always carried auspicious meaning in China, and were standard decoration in the arts long before the Qing dynasty. A profusion of flowers can be found in pre-Qing paintings and on ceramics, among many other art forms. The millefleurs pattern consisting of nothing but flowers, however, while it may find its origins in ancient China, seems to owe its popularity in the Qing period to the influence of European subject matter. European enamels from France and Italy were among the many gifts received by the Chinese court from the seventeenth century onwards, dispensed freely in an attempt to gain access to the highest levels of power on behalf of Christianity and diplomacy. It was these enamels that first inspired the Kangxi emperor to set up workshops at the palace to produce painted enamels on metal and glass and that also informed the decoration on many of them. They also inspired the early workshops in Guangzhou, where many of the gifts and most of the enamellers from Europe passed through on their way to Beijing. One only has to look at seventeenth-century European enamels to discover the reason for the sudden surge in popularity of the millefleurs design among Chinese enamellers (see, for instance, Garner 1969, plates 2 and 3). The works of Jacques Laudin (circa 1627–1695), the Limoges enameller whose works were copied at Jingdezhen in the Kangxi period, provide an excellent example. There is a two-handled saucer by him or his son (inconveniently, both went under the same name and used the same initials to sign their works) in the Musée de Louvre (Hong Kong Museum of Art and Musée Guimet 1997, no. 123). It is decorated with brightly coloured flowers on a white ground, and could easily have inspired the sort of design we see in Treasury 6, no. 1073. One only has to substitute auspicious Chinese flowers for those of France and allow for individual style in two different artists on opposite sides of the world to discern their underlying similarity.

The present example is one of the most spectacular millefleurs designs known in Qing art and is unique among snuff bottles for its extraordinary artistry and skill. The profusion of blooms piled one on another with only a few green leaves as relief manages to avoid both confusion and a sense of excess, despite the wide range of flowers depicted. It is a difficult task, managed with astonishing compositional grace and, for the snuff-bottle world, the tour-de-force of the subject. We know that such designs were made early in the Qianlong reign. In 1737 (tenth month, eleventh day) records relating to the enamel workshop show the completion of two snuff bottles for presentation to the emperor, one of which is described as being decorated with a Baihua xianrui (One hundred auspicious flowers) design. It may have been such a bottle as this.

As always in Chinese art, the design was intended to be read for its symbolic meaning as well as enjoyed visually, and the various flowers all carry their own meaning, but here there are so many that we are willing to pass over this and stick to the overriding symbolism of splendour and prosperity.

There is a useful lesson for collectors to be learned from the recent history of this bottle. The collection of the legendary collector Martin Schoen passed at his death to the stewardship of his daughter Belle. Many bottles were disposed of over the years; Treasury 6, no. 1079, for example, went to Paul Bernat, another famous American collector (though of a wider range of enamelled wares). The snuff-bottle world rather lost track of the Schoen family and his bottles until Joseph Silver discovered that some of the finest still remained with his daughter. He went to visit her and pulled off one of the great recent coups among snuff-bottle collectors by buying, among other bottles, the stunning black ground, enamelled glass bottle that ended up in the J & J Collection (Moss, Graham, and Tsang 1993, no. 184). Typically over-the-top, the proud new owner, at the convention of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society immediately following his coup, displayed his treasures in a rented cabinet flanked by two strapping young security guards – also rented, but this time from the Israeli Army. At the time of Silver's triumph, this bottle was also available, but he turned it down because it had small areas of enamel missing, the result of being dropped at some stage. When the late Bob Kleiner, Robert's father, got wind of the story and learned that Silver had left a major enamel behind, he flew straight to New York to see Belle Schoen and bought it. Subsequently invisibly restored, it is one of those works of art that is so exceptional that a little damage makes no difference at all to its overall appeal. The bottle is unique; no alternative perfect example could be found to lessen its reputation, and its value as a work of art remains, therefore, undiminished. Enamels on metal are particularly vulnerable to damage, since the fragile glassy surface is not particularly compatible with the metal ground, and any severe blow is almost certain to cause a flake of enamel to come away from the metal. A significant proportion of palace enamels on metal have small chips and flakes that have been restored, and if the restoration is sensitive and in no way mars the original visual appeal, it is quite acceptable and can be safely ignored in artistic terms. Today, only an optimist willing to settle for a very small collection would begin to collect imperial enamelled metal snuff bottles with a zero-restoration policy.

Many of the finest palace enamelled metal snuff bottles have a slightly recessed foot, as discussed under the next entry, Treasury 6, no. 1082. This is an extreme example of the phenomenon, the foot being almost on the same plane as the footrim.

百花齊開

銅胎畫琺瑯,描金;平唇、凹底、平底矮圈足;通體繪各種花與葉子,短頸與肩部交接處畫雲紋一道,其上有黃地海棠花與葉子紋一周,圈足繪黃地轉枝形式化花紋;底藍楷書"乾隆年製"四字篆款;壺內施因烘烤失敗而不均勻的綠松琺瑯

御製品,宮廷作坊,1736~1770

高:5.27 厘米

口經/唇經:0.80/1.25 厘米

蓋:描金青銅,鏤刻形式化花卉;大概為原件

狀態敘述:有溺綠色和寶石紅色的牡丹那一正面有修復處, 在紅色牡丹的右下,最大的寬度約1厘米;一側面中間的黃色花下亦有修復處,其最大的寬度為0.9厘米;底有擦痕,本壺因長久的觸摸亦有常見的擦痕和碰痕,但都是肉眼所看不見的;描金的狀態異乎尋常地好,一般的外貌極善

來源:Martin Schoen

Belle Schoen

White Wings 珍藏 (1993)

文獻:Perry 1960, 頁145, 編號154

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1993年冬期,頁10 圖10

Kleiner 1994a, 插圖3,左下

《國際中國鼻煙壺協會的學術期刊》Journal of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society, 1995年夏期,頁35 圖2

Kleiner 1995, 編號9、護封

Kleiner 1997, 編號2

Curtis 1999, 頁79,圖6

Treasury 6, 編號1081

展覽﹕

大英博物館, 倫敦, 1995年6月~10月

Israel Museum, 耶路撒冷, 1997年7 月~11月

說明:百花紋,清朝以前就有,百花紋在清代盛極一時,恐怕跟歐洲琺瑯彩圖案的影響有關係。十七世紀中,類似百花紋的圖案在西洋很流行( 參閱 Garner 1969, 插圖2、3),也流傳到大清帝國。陳偉、周文姬2004, 頁143說﹕"法國印度公司的商人或傳教士們把里摩日琺瑯餐具帶到廣州,然後又輾轉流傳到景德鎮,並且特地請景德鎮的匠師們模仿。在法國,發現存了景德鎮模仿里摩日琺瑯餐具的瓷碗,兩旁有把柄, 碗底畫著西洋寫生法的花籃和花卉,在花籃附近還寫著 "J L"的外文字母。根據歐洲學者們的考證,一致認為,"J L" 是里摩日17世紀琺瑯藝術家勞丁 (J. Laudin) 姓名的縮寫,因此斷定勞丁的琺瑯手工藝品也一定流傳到江西景德鎮。"

本壺是清代藝術上最鮮豔奪目的百花圖案之一。豔而不俗,繁而不亂,實為煙壺界絕技。據檔案,1737年已有所謂"百花仙蕊"一件煙壺為獻給乾隆皇帝作成,大概是此類的煙壺吧。

本壺近來的經歷可給收藏家當前車之鑒。名噪一時的收藏家Martin Schoen仙逝後,他珍藏就由其女,Belle Schoen 女士,繼承。珍藏的煙壺陸陸續續變賣了;譬如,此場拍賣會的拍賣品號67是歸另一位有名聲的美國收藏家,Paul Bernat賞藏的。 過了幾年,Schoen珍藏漸漸門可羅雀了,而收藏家Joseph Silver 突然發覺Belle女士那兒還有不少精品,訪問她,果然很多卓絕群倫的鼻煙壺暴光了。繼而開了國際中國鼻煙壺協會的年會,Silver氏沾沾自喜,租了一個古玩櫃,賃了一雙以色列兵士當保安人員,擺列了他的珍寶讓到會者欽欽敬敬。但有件可觀的琺瑯煙壺,因為琺瑯有所脫落,Silver氏沒有買下。Bob Kleiner (已故,Robert Kleiner 的父親)聞風,趕快地跑到紐約去拜訪Belle女士,把那件煙壺買了,那就是本壺。本壺沒有第二件,即使有,金屬胎琺瑯器遭一點撞擊一定會有所脫落,不會保持出坊的狀態。既有脫落,細心修復對這種優秀的煙壺沒有多少影響。如今,想收藏御製金屬胎琺瑯煙壺的人,如果拒收修復過的煙壺的話,要以極小的收藏系列知足。

很多最優秀的宮廷作坊金屬胎琺瑯煙壺呈突出圈足中微斂底,本壺不例外,底與圈足差點兒相平。

Many of the finest bottles at Bonhams were bid for and bought by active collectors from Mainland China, the first time that such strong demand from Chinese buyers has been seen anywhere in the world for Imperial Chinese snuff bottles.

Bonhams’ Head of Chinese Ceramic and Works of Art in Hong Kong Julian King who prepared the auction, said: “Today saw a new buying power in the world market for Imperial Chinese art. This marked an important change in the whole structure of prices for the finest pieces at Bonhams.”

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F51%2F84%2F119589%2F122518624_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F87%2F119589%2F112989160_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F52%2F119589%2F112495720_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F27%2F119589%2F96148405_o.jpg)