Exceptional gem-set pieces from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad @ Christie's London

An exceptional emerald, ruby and diamond-inset enamelled gold parrot. Mughal India, late 18th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

The green enamel body inset with bold floral sprays in diamonds and rubies, the wings with ruby-inset drop-motifs within a border of diamond-inset leaves, the back and tail with similar ruby insets, the head elegantly inset with emeralds along the crest and beak, the beak holding a drilled emerald pendant, the underside of the body with two styles of floral enamelling including white naturalistic narcissi on green enamel and more stylized red flowers on white enamel under the tail, resting on blue, purple and white enamelled feet, fitted on square base with similar inset floral sprays, the base with four domed feet, the pendant chain lacking, in fitted box; 7¾in. (17.7cm.) high. Estimate £400,000 - £600,000

Provenance: By repute originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 23

Notes: During the reigns of the great Mughal emperors, the classical imperial Mughal style of jewellery which had roots in Iran developed and fused with indigenous traditions to produce a distinct style of jewellery and jewelled objects. A love for these glittering pieces was driven by demand from the courts, not just of the Mughals, but also of the Deccani sultans and smaller princedoms. What was an imperial style thus spread to the Muslim courts of the Deccan and Central India as well as the Hindu courts of Rajasthan and South India. Jewels were not just for panoply. They had an essential place in social rituals of the period. One obvious aspect in the Mughal court were the regular ceremonies where the emperor was weighed in precious metals and jewels for these then to be given out as part of a very public display of munificence. Paintings of the eighteenth century show equally ostentatious local courts.

The transmission of styles went both ways - from the Mughal courts to the smaller sultanates and princedoms and vice versa. When Shah Jahan conquered Hyderabad in the Deccan in the first half of the 17th century, he is reported to have received a tribute 'comprising 200 more caskets full of gems and jewelled ornaments.' (W.E.Begley and Z.A.Desai (ed.), The Shah Jahan Nama of 'Inayat Khan. An Abridged History of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, Compiled by his Royal Librarian. The Nineteenth-Century Manuscript Translation of A.R.Fuller (British Library, Add.30.777), Delhi, 1990, pp.404-05). By repute, all of the pieces of this group (lots 43-50) are said to come originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad, therein suggesting a Deccani origin.

A Mughal jewelled falcon of somewhat similar style to the present parrot is in the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha (JE.69.2001, Leng Tan, Jewelled Treasures from the Mughal Courts, exhibition catalogue, Doha, 2002, pp.8-15, no.1). That is purported to have been part of the private jewels of Shah Jahan, and to be dated circa 1650. That relates to a group of objects, all dated to the early Mughal period, on account of the special forms into which the gemstones have been set. A related handle, terminating in a dragon's head is in the Al-Sabah Collection (Manuel Keene, Treasury of the World. Jewelled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals, exhibition catalogue, London, 2001, p.125, no. 10.1). This style also features instances in which stones are purposely cut to form the edges of pieces, such as the crest or beak of either the Doha bird or the present example.

A gemset bird of paradise (huma) now in the Royal Collection demonstrates the spread of the from the imperial Mughal court (Jane Roberts (ed.), Royal Treasures. A Golden Jubilee Celebration, London, 2002, pp.332-36, no. 298). This bird originally sat atop Tipu Sultan's throne (circa 1787-93) and was preserved by Colonel Wellesley who was installed as Governor of Seringapatam after the British army stormed Tipu's citadel and took the city on 4 May 1799. Both this example and ours are technically close to the Mughal falcon. Each is set at intervals in the kundan technique with foiled diamonds, rubies and emeralds designed to look like feathers. That the huma can be said with certainty to be from Seringapatam supports the fact that there was production of 'Mughal style' jewelled pieces in central and southern India.

Our parrot combines the kundan with a champlevé enamelled tail similar to the breast of the Doha Mughal falcon. As discussed in the note to lot 49, the origins of the art of enamelling are unclear with various scholars heralding the imperial Mughal workshops, Goa and the Deccan as various centres for its begninnings. What is known is that by the 1620s recipes for various techniques, including enamelling had circulated in Mughal territory and other parts of the subcontinent. The Majmu'at al-sana'i (Collection of Recipes) was copied several times (the earliest is in the Bodleian and dates to AH 1033/1624 AD) and details the recipe for various enamels. This practice serves to explain why similar colours were produced in different regions, and therefore why identifying the specific location where certain pieces were made is sometimes difficult (Pedro Moura Carvalho, Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London, 2010, p. 20).

Birds in connection with Muslim rulers represent victory and power. In the context of a study of the tile cycle of the Hasht Behesht pavilion in Isfahan of 1670, Ingebord Luschey-Schmeisser interpreted winged beings both as an expression of rulership in search of the blessings of the angels and as winged beings who protect and serve their ruler (Ingebord Luschey-Schmeisser, The Pictoral Tile Cycle of Hast Behest in Isfahan and its Iconographic Tradition, Rome, 1978, pp. 47-55). Parrots and other birds often decorate the surfaces of enamelled objects, such as the underside of a pandan box in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC (inv. no. F.1986.22, Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, London, 1997, p.61, no.39). The sculptural form of the present parrot is however rare. With the associated symbolism, it is not surprising that the two other birds known are associated with Shah Jahan and Tipu Sultan. Our parrot adds another very impressive, example to the small extant group.

A fine diamond-inset and enamelled gold covered bowl and stand. Deccan or Mughal India, late 18th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

The stand of circular form with raised rim on six floral feet, the green enamel ground with bold floral sprays inset with flat-cut diamonds, the centre of the stand superbly enamelled with floral sprays and birds on a gold ground, the exterior of the bowl with two tiers of similar floral sprays between minor meandering vine bands, the interior with a stylised leopard engraved under the green enamel, the cover with similar inset floral sprays radiating from the raised central floral boss flanking a square cabochon foiled ruby, the underside of the cover engraved with radiating lobes flanking a lion rampant within a floral meander border, very slight damages to the enamels, in fitted box. Stand 8¼in. (21cm.) diam.; with covered bowl 5¼in. (13.3cm.) high - Estimate £150,000 - £200,000

Provenance: By repute, originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 21

Notes: Visitors arriving at the courts of Indian rulers from the 17th century onwards were unanimously impressed by their material splendour. The lavishness of the interiors that greeted them, highlighted with small accents provided by enamelled and jewelled vessels and utensils, has been recorded time and again. Sir Thomas Roe, who was sent as an embassy to Jahangir in 1615-18 described the Mughal court as 'the treasury of the world' (Susan Strong, Nima Smith and J.C.Harle, A Golden Treasury. Jewellery from the Indian Subcontinent, London, 1989, p.27). The present lot, as well as the others from the same collection (lots 43-50) are examples of the type of jewelled object that would have created this rich impression. Such objects were a way of expressing wealth, and by implication status and military prowess. As discussed in the note to lot 50, the styles used in many of these jewelled objects, including the bright enamels and kundan technique of inlaying stones, spread across the subcontinent and were used not only in the imperial Mughal court, but also in local centres.

In India metal objects, and particularly gold, was habitually melted down if damaged or if fashions changed. The invasion of Nadir Shah of India in 1739 saved for posterity a number of jewelled pieces which he either took back to Iran as booty or, in an overt display, sent with embassies to the rulers of Russian and Turkey. These however constitute the only substantial group of royal Mughal decorative arts in gold to have survived - the St. Petersburg items comprise the largest group of Mughal jewelled objects which survive together. Zebrowski writes that nothing survives in India itself (Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, London, 1997, p.52). The present group therefore represents an important addition to the known cache of jewelled objects of imperial quality.

This fine set of jewelled lidded bowl and stand is an impressively complete survival. In his article entitled 'The Jewelled Objects of Hindustan', Assadullah Souren Melikian- Chirvani, writes that no complete set of jewelled bowl-shaped wine cup with matching cover and salver has been recorded (Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, 'The Jewelled Objects of Hindustan', Jewellery Studies, Vol. X, London, 2004, p.16). Although too large for a wine vessel, this present set adds an interesting comparison to the small group and a suggestion of what comparables would have looked like.

The technique of translucent green champlevé enamelling that covers engraved designs, found on the underside of the lid and stand of this box is similar to that found on an octagonal box attributed to North India, circa 1700, which is in the Khalili Collection (Pedro Moura Carvalho, Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London, 2010, pp.26-7, no. 3). There the undersides are carved with central flowerheads within a lattice of leafy lozenges. A more inventive design is seen on a small box, also in the Khalili collection (Pedro Moura Carvalho, op. cit., pp.30-1, no.4) where the interior of the lid is engraved in a similar style with engraved overlapping leaves. The present engraving is reminiscent of the Khalili octagonal box with the leaf lattice. However on the present example, this surrounds the playful figure of a lion. Like the Khalili examples the quality of the decoration is rarely observed in extant pieces and suggests a possible royal commission.

The floral sprays that adorn the sides of the vessel recall those on the sides of a Mughal huqqa set, formerly of the Clive of India Treasure and now in the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha. In that example, a lattice of similar isolated diamond-set floral sprays, each with five petals and issuing two leaves decorated the blue enamelled ground. That set was attributed to Lucknow, circa 1750 on the basis of the colours of the enamels found under the base. For a short note on the techniques used for this group, please see the note to lot 49. A discussion on the Deccani or Mughal attribution can be found in the note to the jewelled parrot, above.

A fine Mughal gem-set silver and gold rosewater sprinkler. North India, , 17th/18th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Of drop form with long slightly tapering tubular neck flaring into a floral knop, the body with emerald and ruby inset medallions divided by vertical rows of pearls, fish-scale motifs set with emeralds and rubies below, the underside of the foot with a similar rosette within a stylised wreath, the edge with later numerical inscription, the gold neck with similar fish-scale set with cabochon rubies, the flower finial similar, neck possibly an 18th century replacement, in fitted box; 10in. (25.5cm.) high - Estimate £80,000 - £120,000

Provenance: By repute, originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 24

Notes: This rosewater sprinkler (gulabpash) is part of a small group of imperial-quality pieces that were decorated exclusively with gems. Three very similar rosewater sprinklers are in the Hermitage Museum (V3-709 and V3-714, all published in Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, London, 1997, p.70, nos.49, 50 and 51). All are dated to the 17th century were probably part of the embassy sent to Russia by Nadir Shah in the 18th century. The pieces included in the chapter 'Jewelled Magnificence' in the book Treasury of the World. Jewelled Arts of Indian in the Age of the Mughals also fall into the same group (Manuel Keene, London, 2001, pp.70-154). All are similarly heavily encrusted with gemstones within gold settings and are attributed to Mughal India, 17th century.

A fine enamelled and gem-set gold covered jar. Deccan or Mughal India, 18th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

With bulbous body on short conical foot, with flaring lip, the domed cover with floral knop, the green enamel ground inset with stepped rows of diamond and ruby bud-motifs, a band of ruby inset meandering vine below, the cover with similar motifs, the interior plain gold, the underside of the foot with fine floral enamelling in red, blue and green on white ground, dent to the lip, in fitted box; 5in. (12.6cm.) high - Estimate £50,000 - £70,000

Provenance: By repute originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 19

Notes: Abu'l Fazl's Ain-i Akbari (Institutes of Akbar), a late 16th century detailed document recording the administration of the emperor Akbar's empire gives a technical description of the practices used within the royal karkhana or workshop, and provides us with an insight into the techniques used to produce pieces such as these. It records that each skill was specific to a different professional, such as an enameller (minakar), engraver (zar nishan) or one practiced in the setting of gems. An individual object, such as this and the others of this group, would therefore have been worked on by a number of craftsmen.

A quintessentially Indian technique, recorded by Abu'l Fazl and used throughout the present group (lots 43-50) is that of kundan or setting of stones. This technique is practiced from the Akbari period until the 19th century when claw settings were introduced via Western jewellery. Susan Strong et al give a comprehensive description of how this technique is carried out - 'the piecesare shaped by the relevant craftsmen and left in separate, hollow halves. Holes are cut for the stones, and any engraving or chasing is carried out, and the pieces are enamelled. When the stones are to be set, lac is inserted in the back, and is then visible from the front through the holes for the stones. Highly refined gold, the kundan, is then used to cover the lac and the stone is pushed into the kundan. More kundan is applied round the edges to strengthen the setting and give a neater appearance' (Susan Strong, Nima Smith and J.C.Harle, A Golden Treasury. Jewellery from the Indian Subcontinent, London, 1989, p.30).

Another defining feature of this group of objects is the use of enamels (mina). How and when enamelling was introduced into the Mughal court is unclear. It has been suggested by some that it reached Mughal India through Goa - 16th century pieces made in Goa confirm that local craftsmen had mastered European techniques (Pedro Moura Carvalho, Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London, 2010, p.19). The first known pieces so decorated are an oratory-reliquary and a gold filigree casket, both now in Lisbon and produced in the late 16th century (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon, inv. nos. 99 and 577). Akbar sent a cultural mission to Goa in 1575 so it is possible that the technique was learnt there. Manuel Keene has recently suggested that from Goa the enamelling may have spread first to the Deccan (Manuel Keene, Treasury of the World. Jewelled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals, exhibition catalogue, London, 2001, p.62.

The way in which the diamonds are set into repeated drop-shaped settings recalls a pair of fly-whisk handles, attributed to Rajasthan (probably Jaipur) circa 1750, which are presently in the Khalili Collection (Pedro Moura Carvalho, Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London, 2010, pp.74-5, no. 19). For a general note on the group of enamelled and gemset objects please see lot 44.

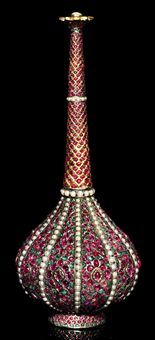

A fine enamelled and gem-set gold rosewater sprinkler. Deccan or Mughal India, late 18th/early 19th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Rising from a domed foot through the spherical body to the trumpet-shaped collar, the long tapering spout terminating in a stylized vase of flowers, the surface inset with diamonds and rubies forming floral sprays on a green enamel ground, floral bands above and below, the neck with stepped rows of similar drop-motifs decreasing in size from bottom to top, the upper flowers with diamond-inset centres, in fitted box; 11¼in. (28.6cm.) high - Estimate £40,000 - £60,000

Provenance: By repute, originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 22

Notes: The rosewater sprinkler (or gulabpash) was much in vogue in the Mughal Empire and across Islamic lands, used to sprinkle honoured guests with rose water when they arrived. Jahangir (1605-27), refers in his memoirs to the festival of the sprinkling of rose water at the royal court, to which the present and the next lot were probably associated, albeit a few decades later, 'the assembly of gulab-pashi [sprinkling of rose water] took place and has become established from amongst customs of former days' (quoted in Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, London, 1997, p.69).

A jewel-encrusted gold-mounted dagger (jambiyya). Yemen and India, late 19th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Of typical form with waisted grip and sharply curving sheath terminating in a ball knop, the watered steel blade with medial ridge, the hilt and sheath probably bejewelled in India with extensive floral and geometric design in diamonds, rubies and emeralds, in fitted box; 12½in. (31.8cm.) long - Estimate £30,000 - £50,000

Provenance: By repute, originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 8

Notes: The Chaush are a Muslim community of Hadhrami Arab descent found in the Deccani region of India. The name Chaush derives from the Turkish for military personnel, as many of them served in the armies of the Deccani rulers. They also retained very close ties with the Southern Arabian peninsula, their homeland. It is recorded, that traditionally the Chaush would wear jambiyyas at their waists. This explains the practice of sending such weapons from the Yemen to the Deccan to be decorated in this manner. A number of examples of Indian decorated jambiyyas are known; amongst them this is one of the most opulently decorated of all.

A mutton-fat jade covered bowl. India, 19th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Of hemispherical form on short conical foot, the sides with floral sprays inset with emeralds and diamonds alternating with rubies and diamonds, below the lip a ruby and diamond arcade, the cover with similar alternating floral sprays around a central and slightly raised square panel similarly decorated, with a diamond set knop, the cover's border with a band of trefoils inset with pearls and diamonds, in fitted box; 6 1/8in. (15.6cm.) diam. - Estimate £15,000 - £20,000

Provenance: By repute, originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 12

A diamond and turquoise-inset and gold-inlaid pale jade saucer. India, circa 1900. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Of shallow form with raised lip, the interior with a vacant central circle surrounded by lobed border issuing turquoise-inlaid palmettes, beyond these a series of floral sprays issuing similar palmettes and diamond-inset leaves, the edge with similar lobed border, in fitted box; 5½in. (14cm.) diam. Estimate £6,000 - £8,000

Provenance: By repute, originally from the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad,

Anon sale, Habsburg Feldman, Geneva, 9 November 1987, lot 10

Christie's. Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds, 5 October 2010, London, King Street www.christies.com

Nizam of Hyderabad, is Fifth on Forbes ‘All Time Wealthiest’ list of 2008 with Net Worth: 210.8 Billion USD.

This is a list of historical figures who lived during the Industrial age, Information Age, Middle Ages, Ancient world and is solely based on net worth accumulated by inheritance or personal earnings. The estimated net worth of these people is calculated into inflation-adjusted 2007 dollars, from when historical figures were at the peak of their net worth

Last Nizam of Princely State of Hyderabad and Berar, Fath Jang Nawab Mir Osman Ali Khan Asaf Jah VII, was The Richest Man in the 1940s, having a fortune estimated at $2 billion. He ruled Hyderabad between 1911 and 1948 until it was made part of India as a result of Operation Polo launched by the Indian Government.

Nizam of Hyderabad even featured on the cover of TIME magazine. While rulers of other big states like Kashmir, Jodhpur Bikaner, Indore, and Bhopal were given the title of “His Excellency” (H.E.), the Nizam of Hyderabad alone had the title of “His Exalted Highness” (H.E.H.)

During the rule of Aurangzeb’s great grandson Muhammad Shah (1719-1748), the governor of Deccan was one Nizam-ul-Mulk. In 1723 he decided to carve himself a kingdom. Another Mughal functionary, Mubariz Khan had created a near independent state in Hyderabad, which was attacked by the Nizam in 1724. After forsaking his capital in Aurangabad, the Nizam moved to Hyderabad and founded the strongest independent Muslim state of the South.

Later Nizams played puppet pawns in the hands of the British and the French of Pondicherry. After French were defeated by the British, the Nizam of Hyderabad switched his allegiance to the British and ruled till Independence of India under British protection.

When India attained her Independence, and Sardar Patel was in the process of integrating India’s princely states, Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh and Hyderabad decided to sought accession with Pakistan or declare independence. Hyderabad was the largest of the princely states, and included parts of present-day Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Maharashtra states. Its ruler, the Nizam Osman Ali Khan was a Muslim, although over 80% of its people were Hindu. The Nizam of Hyderabad kept on changing his position and Patel could take no more.

Patel ordered the Indian Army to integrate Hyderabad (in his capacity as Acting Prime Minister) when Nehru was touring Europe.The action was termed Operation Polo, in which thousands of Razakar forces had been killed, but Hyderabad was comfortably secured into the Indian Union.

Post Operation Polo, Nizam of Hyderabad had lost all its powers, and was merely a ceremonial chief of the state.

Hyderabad, over the course of seven generations of Nizams, had become the richest state of the world. However, the world related most to its seventh ruler, Mir Osaman Ali Khan who is famous for his idiosyncrasies and wealth. He negotiated with the Portuguese in the 1940s to buy Goa from them. He owned world’s grandiose treasures but lived like a pauper, smoke cheap bidhis, and wear tattered clothes.

His collection of pearls alone could fill up an Olympic size swimming pool. He gained the famous Jacob Diamond – the 400 carat diamond (left), double the size of the Kohinoor and world’s fifth largest, through a famous ‘Diamond Suit’ in 1892. The Jacob Diamond was later purchased by the Government of India in 1995 after a battle of 24 years with the Nizam’s trust for an estimated $13 million along with other Jewels of The Nizams, and is held at the Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai. The value of Jacob Diamond alone is 100 million pounds. The seventh and last Nizam found the duck-egg-sized diamond hidden in his father’s slippers and used it as a paperweight.

His collection of pearls alone could fill up an Olympic size swimming pool. He gained the famous Jacob Diamond – the 400 carat diamond (left), double the size of the Kohinoor and world’s fifth largest, through a famous ‘Diamond Suit’ in 1892. The Jacob Diamond was later purchased by the Government of India in 1995 after a battle of 24 years with the Nizam’s trust for an estimated $13 million along with other Jewels of The Nizams, and is held at the Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai. The value of Jacob Diamond alone is 100 million pounds. The seventh and last Nizam found the duck-egg-sized diamond hidden in his father’s slippers and used it as a paperweight.

"Times reported on Feb 22, 1937 – Most news stories hung on the Richest Man are chiefly chatter about how careful His Exalted Highness is with his pennies — whereas $5,000 is his approximate daily income, his jewels have an estimated value of $150,000,000, he reputedly has salted down $250,000,000 in gold bars and his capital totals some $1,400,000,000, not to mention the fabled “Mines of Golconda…

…The cash Silver Jubilee gifts to the Nizam of Hyderabad, by his subjects were expected this week to total at least $ 1,000,000."

Nizam’s Jewels, valued at $ 250- $ 350 million by the Sotheby’s and Christie’s, date back to early 18th century to early 20 century. Crafted in gold and silver and embellished with enameling, the jewels are set with Colombian emeralds, diamonds from the Golconda mines, Burmese rubies and spinels, and pearls from Basra and Gulf of Mannar.

While India thought they had settled all deals with the Nizams and their 200 heirs, they are back in the news.

Osman Ali Khan nominated not his son, but grandson Mukarram Jah (born in France and had Turkish mother), to be the next (and last) titled Nizam of Hyderabad. Mukarram Jah could not take the battles over his grandfather’s wealth and escaped to Australia where in spite of having the best possible education money could buy (Harrow, Cambridge, LSE, Sandhurst), he run bulldozers, married and divorced five times, one of them being former Miss Turkey. He now lives in a two room apartment in Istanbul, Turkey.

Nizam of Hyderabad is reported to have impregnated 86 of his mistresses, siring more than 100 illegitimate children and a sea of rival claimants.

However, Jah has not been able to escape it all. He has four sons and a daughter from his five wives. The eldest of them, Azmet Jah, a cameraman in Hollywood who has worked with Steven Spielberg, Richard Attenborough, Nicolas Roeg, hopes to come back to Hyderabad.

“I am determined to maintain what has been saved. We’ll not make the same mistakes again.”

His mother Esra has been visiting Hyderabad and overlooking the work of restoration of Palace Chowmahalla which was compared to the Enchanted Gardens of the Arabian Nights.

India is now on its way to make a final deal with the Nizams. Today, Government of India agreed for an out-of-court settlement with Pakistan and descendants of Nizam of Hyderabad. Mir Osaman Ali Khan had on September 20, 1948 transfered one million pounds maintained in the account of the Nizam of Hyderabad’s government in National Westminster Bank to an account of Habib Ibrahim Rahimtoola, the then Pakistani High Commissioner to Britain, as the Nizam dithered over which of the two new nations to join. He then cabled the bank to freeze the transaction when pressured by the government of India.

In 1957, after several rounds of litigation between the Nizam and the Pakistani government, the case reached Britain’s House of Lords, which ruled that the account could only be unfrozen with the agreement of all the parties.

The amount has grown to about 30 million pound sterling and New Delhi intends to broker a compromise with the two heirs of the Nizam of Hyderabad and Pakistan. Will it be easy?

Mr Muhammad Safiullah, cultural adviser to the Nizam’s Trust, said,”Mir Osman Ali Khan’s grandsons Shahmat Jah, Mufakham Jah and Mukarram Jah, granddaughter Fatima Fouzia and other family members have all staked claim to part of the funds. Since there’s no Nizam government now, the Nizam’s trust and his legal heirs will also get a part of the money. The ruler wanted to help the nascent Pakistani governmen in 1948 as it had no money to pay even the salaries of its employees.”

Nizam’s heirs do not wish to share the money with either India or Pakistan. “The money is ours and we alone are the legal heirs. Once the matters become clear, we will lay claim,” they say.

Almost sixty years after Independence, and 37 years after Indira Gandhi abolished the Privy Purses, our fascination with the fortunes of India’s maharajahs and nizams has not abated it seems! (helloji.wordpress.com)

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F96%2F119589%2F129836760_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F33%2F99%2F119589%2F129627838_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F83%2F119589%2F129627729_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F37%2F119589%2F129627693_o.jpg)