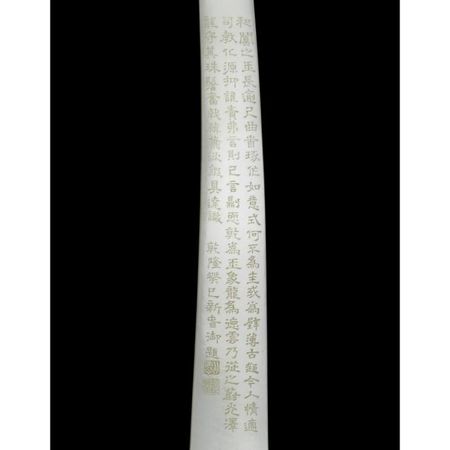

An extremely rare white jade 'dragon' ruyi sceptre with imperial poem. Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, dated to the guisi year

An extremely rare white jade 'dragon' ruyi sceptre with imperial poem. Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, dated to the guisi year (1773). photo courtesy Sotheby's

the slender curved sceptre elegantly carved on the head with a sinuous dragon in relief, in pursuit of a 'flaming pearl', above a shaft carved with an Imperial poem Yong Baiyu Yunlong Ruyi ('Song on a Cloud and Dragon Ruyi Sceptre'), dated to the guisi year of the Qianlong reign corresponding to 1773, followed by two seals, the stone of an even white tone with russet veins; 37.5 cm., 14 3/4 in. Estimate 7,000,000—9,000,000 HKD. Lot Sold 18,580,000 HKD

PROVENANCE: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 25th November 1987, lot 370.

EXHIBITED: Chinese Jade from Southern California Collections, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 1977, cat. no. 37.

LITERATURE AND REFERENCES: 'A Collection of Chinese Carved Jade', Lapidary Journal, June 1979, p. 670 (Illustrated).

Peter O. Keller and Wang Fuquan, 'A Survey of the Gemstone Resort of China', Gem & Gemology, vol. XXII, Spring 1986, fig. 7.

NOTE: The poem can be translated as follows:

'Song on a Cloud and Dragon Ruyi Sceptre', dated to 23rd January 1773 or shortly after

Yuzhi shiji (Poetry Collection by His Majesty), Siji (Fourth Collection) (Siku quanshu ed.), 9:2b

This Hetian jade,

more than a foot long,

With curled head, is carved

into the shape of a ruyi,

But why wasn't it made into a gui tablet

or a bi disk?

To slight the old and favour the new

has always suited people's taste,

But who else should be responsible for managing

the font of moral culture?

So if I don't speak out, nothing will come of it,

but if I do, I should be ashamed.

Qian is the image for this jade,

dragon is its virtue,

Thus clouds follow after it,

all in lustrous sky blue.

Back fin standing up in daggers,

the dragon guards its pearl,

If any artemisia plaiter wishes to wear it at his neck,

his competence and knowledge must be complete.

Masterly carved with a sinuous dragon in pursuit of a 'flaming pearl' in high relief and incised with Qianlong emperor's poem titled 'Song on a Cloud and Dragon Ruyi Sceptre', the present elegantly shaped sceptre is a fine example of Imperial jade carvings of the 18th century. The inscription is dated to the guisi year of Qianlong's reign (corresponding to 1773), a poem the emperor wrote at the age of 62. 1773 was a significant year for Qianlong: it was the year when work was launched on the largest literary compilation of books in China's history commissioned by him, the Siku Quanshu (The Complete Library of Four Treasuries). The project took nine years to complete with the binding of 3470 works with a total of 79,932 chapters – over 360 million words in 36,000 volumes. Seven copies were made in total with four kept in various palaces in Beijing and one each in Yangzhou, Hangzhou and Zhenjiang where scholars and officials had access to them. The Siku Quanshu is one of Qianlong's most important legacies that surpassed the Ming dynasty's Yongle Dadian (The Great Cannon of the Yongle Era), compiled between 1403 and 1408, and known as the world's largest encyclopedia. The editorial board of the project included 361 scholars, with Ji Yun (d. 1805) and Lu Xixiong (d.1792) two of Qianlong's most trusted and capable scholar-officials, as chief editors. Many of those working on the board were not paid in cash but were rewarded with official posts and bestowed with a ruyi sceptre by the emperor as was customary at the time.

Qianlong was particularly fond of sceptres and not only commissioned the Palace Workshops to make them for his worthy and loyal officials as gifts but to be included in his own extensive collection. While many of his sceptres were decorated in a luxurious manner to satisfy his fondness for the opulent, or were made in a medium that suggested lavish extravagance, this jade sceptre is elegantly simple. The size of this sceptre suggests that it was made using a generous size boulder. It is also masterly carved and polished, with the design of the dragon and clouds, symbols of high rank and power, expertly placed to take advantage of the material's natural beauty.

The history of sceptres dates back to the pre-Tang (618-907) times, with its origins connected to Buddhism. Originally used as back-scratchers, often depicted in the hands of Buddhist holy figures, the ruyi sceptre became a talisman that was presented to bestow good fortune. Its shape changed over time and from the latter half of the Tang dynasty when there was a temporary decline of Buddhism, Daoist adopted it as their lucky object. From that time onwards, the heart-shaped head was often rendered as a lingzhi fungus, a symbol of longevity. Since the sceptre had no practical function it could take on any shape or form deemed suitable to express good wishes. It was during the reign of the Yongzheng emperor (1722-1735), Qianlong's father, that the auspicious tradition of the ruyi (literally meaning 'as you wish') was revived and became an imperial object. The sceptre's auspicious nature and the fact that the choice of materials was virtually unlimited and the craftsmen could leave free reign to their imagination, made sceptres the perfect Imperial gift. Both Yongzheng and Qianlong had themselves painted holding ruyi sceptres, but it was Qianlong in particular who had a great fondness for them and owned a large collection, many of which are on display in the Forbidden City in Beijing, from the Qing Court collection and now in the Palace Museum. For a more detailed discussion of the history of this good luck charm see the exhibition catalogue Auspicious Ju-I Sceptres of China, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1995.

The poem describes the sceptre being made of jade mined from the small town of Hetian, located in Xingjiang province in northwest China. Hetian became famous for its exquisite, translucent and pure white flawless jade which had a history that originated in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) when jade was used for making sacrificial vessels. In his poem Qianlong expresses his concern for 'slighting the old and favouring the new' and describes his responsibility as the ruler to set standards for the moral fibre of society. The compilation of the Siku Quanshu prompted Qianlong to review and edit classical literary material that would lay down the principles for his 'ideal' society. The last line of the poem alludes to a passage in the Zhuangzi (Sayings of the Master Zhuang). Using the story from the Zhuangzi, Qianlong warns himself that he must continue to perfect himself and be 'competent and knowledgeable'.

Three white jade ruyi sceptres carved with dragons on the handles, all inscribed with Qianlong poems, in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, were included in the museum's exhibition op.cit., cat. nos. 13-15, dated in accordance with 1774 and 1789 (twice). For other examples see one in the Palace Museum, Beijing, included in the exhibition The Three Emperors, 1662-1795, The Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2006, cat. no. 282, engraved with dragons amongst clouds but made of a greyish-green jades stone. Another sceptre with a dragon carved on the handle and the ruyi-shaped head decorated with clouds, published in A Romance with Jade from the De An Tang Collection, Hong Kong, 2004, pl. 19, was sold in these rooms, 1st November 1999, lot 561; and one carved with a ferocious scaly dragon in pursuit of a 'flaming pearl' on the large ruyi-shaped head was also sold in these rooms, 9th October 2007, lot 1310.

Sotheby's. An Important Private Collection of Qing Historical Works of Art, 07 Oct 10, Hong Kong www.sothebys.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240406%2Fob_a54acc_435229368-1644755382961141-18285727260.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240229%2Fob_b1ea4c_429582962-1625285201574826-43586635599.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240229%2Fob_84bc3b_429558450-1624783464958333-37673404077.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F36%2F88%2F119589%2F129555285_o.jpg)