Sotheby's announces first dedicated sale of fine Classical Chinese paintings

Dong Qichang, Calligraphy in Running Script. Ink on paper, album of eight leaves, 17th century. Est. $200/300,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

NEW YORK, N.Y.- On Tuesday 13 September 2011 Sotheby’s will present Fine Classical Chinese Paintings, the first dedicated New York auction in this category for over a decade. The sale is made up of 80 diverse works from the Ming and Qing dynasties, as well as a small selection of modern and contemporary works that were executed clearly in the classical manner. The pre-sale exhibition opens on Friday 9 September.

The sale is led by Running Script Transcription of an Epitaph, written for Minister Chen Xinyi by Dong Qichang who is known as the most influential artist of his time (lot 47, est. $200/300,000).* The eight-leaf album, which has been expertly kept in its original 1850s mountings, was appraised by its then famed collector Kong Guangtao as “…genuinely stately and thoughtful in spirit, so fluid and elegant as if executed with divine power”.

Dong Qichang (1555-1636), Running Script Transcription of an Epitaph, written for Minister Chen Xinyi . Photo: Sotheby's

igned Dong Qichang, inscribed, with two artist's seals, zong bo xue shi, dong shi xuan zai, and ten collector's seals, ting yu, zhuang lie bo zhang, wu chen jin shi shi xue ling nan, ceng zai jing yin cao tang, wu lin weng shi shen ding ji, song nian mu shang, tian nan sheng yi, nan hai kong guang tao shen ding jin shi shu hua yin, shao tang han mo, yue xue lou jian cang jin shi shu hua tu ji zhi zhang, shao tang mo yuan. Inscribed by Li Tingyu and Kong Guangtao; ink on paper, album of eight leaves ; each 35.2 by 31.7 cm. 13 7/8 by 12 1/2 in. (8). Estimate 200,000-300,000 USD

PROVENANCE: Famous 19th Century Collector Kong Guangtao

Chang Pi-han (Zhang Bihan), Piedmont, California

LITERATURE: Yuexueloushuhualu, Vol. 4, Kong Guangtao (ed.), Preface 1861, p. 125-127

Dong Qichang xinian, Ren Daobin (ed.) (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, March 1988), p. 197.

Floating Studio: the Role of Water Travel in Chinese Calligraphy and Painting , Fu Shen, published in Meishushi yanjiu jikan (Journal of the Study of Art History), no. 15 (Taipei, 2003), p. 273.

NOTE

Artist's inscription:

The Vice Minister of Justice makes this calligraphy of Epitaph a present for Minister Chen Xinyi.

[Text of the stele not recorded.]

Granted the titles of Tongyi Daifu based on the Jinshi rank as well as Minister of Zhanshifu at the Ministry of Rites, assisting the affairs at the imperial household, and also Academician Reader-in-waiting at the Hanlin Academy, who later received the orders to compile and edit the historical records from the former two dynasties and document the imperial chronicles. The Lecturer of the Imperial Household Dong Qichang.

Collector's inscriptions:

[Li] I have reviewed quite a lot of Xiangguang's writing. However, I have never seen such an unusual and peculiar piece. Both the present work's calligraphy and text are wonderfully refined, probably equaling the stylistic quality of Zhengzuo tie and Erji gao. People are so enchanted by these two masterpieces that they might not realize how similar they are to each other. Master Chen Xinyi is an honest and thoughtful man, who was a great literatus with status in Ming times. After his passing, his virtues and reputation were even more highly regarded by everyone. Generally speaking, people skilled in calligraphy are usually willing to write for others. It's wonderful that this is such a powerful piece. After reviewing it several times, I simply became more impressed and in awe. The time is the end of the tenth month of the fall, in the year dingyou (1837). I was shown this album and asked to give an inscription. I may not be well-versed in the field of calligraphy, but upon opening the work, I can determine that this is a piece of the finest quality in the tradition of Jin and Tang, even though I cannot expound upon such distinct features at great length.Please correct me immediately so that I know whether my remarks are appropriate or not.

Recorded by Runtang Li Tingyu.

[Kong] Over my entire life, I've already reviewed several hundred examples of Wenmin's work. Many of them appear unnecessarily fast and slick. But this piece is genuinely stately and thoughtful in spirit, so fluid and elegant as if executed with divine power. Compared with the brushwork of Zuowei tie, one can see that it is written in the style of Zhao Mengfu combined with the basic structure of Yan Zhenqing, which seems to further enhance the remarkable presence of the writing. This is not a regular work by Dong, many of which do not even come close to this piece. I have recently examined another example of Dong's writing, Shengzhu de xiancheng song, which was once in Emperor Qianlong's Shiqu imperial collection. The writing of that piece displays grace and poise, while this present one possesses vigorous and assertive spirit; both of them can be regarded the best of Dong's calligraphic works. The day of Chongjiu Festival, the ninth day of the ninth month of the year wuwu, reign of Xianfeng (October 15, 1858). Intoxicated by drinking the chrysanthemum wine, I washed the inkstone in order to try out my new brushes. Written in Yuexue lou studio by Nanhai Kong Guangtao.

Chen Yumo, literary name Mengwen, studio name Xinyi, a native of Renhe, Zhejiang province. A Jinshi in the year Chen Yumo, literary name Mengwen, studio name Xinyi, a native of Renhe, Zhejiang province. A Jinshi in the year the office of Supervisor of Jiangxi province and retired as the Vice Minister for the Ministry of Justice. He died in the eighth month of the year 1622.

Both Ren Daobing and Fu state that this work was executed in the eighth lunar month of the year dingchou of the Wanli reign (1577), he was first assigned the secretariat position of Zhongshu, and later promoted to the office of Supervisor of Jiangxi province and retired as the Vice Minister for the Ministry of Justice. He died in the eighth month of the year 1622.

Both Ren Daobing and Fu state that this work was executed in the eighth lunar month of the year 1622.

This album was in the collection of Yuexuelou assembled by Kong Guangtao and his family from Nanhai. It is recorded in juan 4 of the four-volume Record of Paintings and Calligraphy in the Collection of Yuexuelou published in the eleventh year of Xianfeng reign (1861). The album retains its original mounting and original wooden box. The work's title is inscribed on the front of the box and again on the side, which reaffirms that this piece was cherished by the Kong family.

The writer of the titleslip is Meng Hongguang, literary name Pusheng, sobriquet names Yinjue jushi, Xiaomeng Shanren, Lujian Zhenren, and studio names Zhuanchou lu, Meixuexuan, etc. Meng, a native of Zhejiang, resided in Panyu, Guangdong province. He became a provincial graduate in the jiawu year of the Daoguang reign (1834). With his encyclopedic knowledge and photographic memory, Meng devoted his life to teaching, at one time running a private school in Guangzhou. He excelled in poetry and linguistics, and was good at calligraphy and seal carving. Meng also befriended Chen Li because of their common interest in the study of epigraphy. His published works include the Collected Poems by Lujian Zhenren, and the Seals of Meixuexuan.

Li Tingyu (1792-1861), literary name Runtang, and studio name Heqiao, a native of Fujian, served as the commanderin-chief for Fujian Navy and fought alongside Lin Zexu in the Sino-British Opium War. Well versed in both military and literary matters, Li excelled in painting orchids, and was fond of collecting painting, calligraphy, seals, and ink stones. He authored books on both military and literary subjects, including A New View of Territorial Sea of the Seven Provinces and Record of Inscriptions on Paintings and Calligraphies by Meiyintang, etc.

Chang Pi-han (Zhang Bihan), studio name Jing Yintang, a native of Jiading, Jiangsu province, graduated from Hujiang University in Shanghai. He was a famed collector, connoisseur, and artist. He studied with Zhao Mengsu, a local master from the age of thirteen; later, he studied under the tutelage of Wu Hufan and Feng Chaoran. In the 1940s, he co-founded Lüyishe (Green Ripple Society) along with Ying Yeping, Wang Jiqian, Xu Bangda, and others. He immigrated to Hong Kong in 1948, and taught at the Department of Fine Arts at the New Asia College, Chinese University of Hong Kong, from 1957 until his retirement in 1974. At the end of 1970s, he immigrated to California. Chang Pi-han's in-depth study of Classical Chinese paintings and connoisseurship earned him the role of consultant to the Hong Kong Art Museum. His collection of paintings and calligraphies from Ming and Qing dynasties were well known at the time. Among his published works is Collected Works by Chang Pi-han.

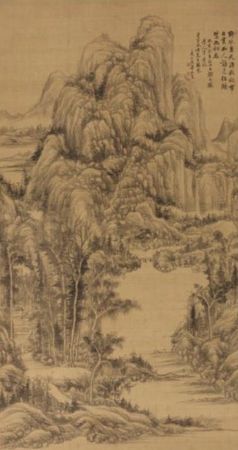

Thatched Hut in Autumnal Mountains by Dong Bangda, who was admired and highly praised by Emperor Qianlong, is a further highlight (lot 23, est. $180/250,000). The grandly composed landscape executed on silk conveys such free, refined brushwork that it is conspicuous among the artists repertoire.

Dong Bangda (1699-1769), Thatched Hut in Autumnal Mountains. Photo: Sotheby's

signed Dongshan di Dong Bangda, dated guihai (1743), and with three seals of the artist, dong bang da, fu cun, yong zhuo, and four collector's seals, lai jiang pan shi lian zhen cang, nan yai zhen cang, lu he liu shi zhen shang, zhao xiang; ink on silk, hanging scroll, 128.7 by 71 cm. 50 3/4 by 28 in. 1743. Estimate 180,000-250,000 USD

NOTE.

Label inscription:

An exquisite work of ink landscape painting by Dong Dongshan of the Qing dynasty. Inscribed by Tuiweng

Artist's inscription:

Wild rivers paired with the sky, clear and crisp,

Autumnal woods, tinted with the yellow glow of daylight;

The hermit wonders who is to keep him company,

The gull and heron are unaware of each other's presence.

In the year of guihai (1743), ten days after the summer solstice, [I] imitated the brushwork of Dachi Daoren (Huang Gongwang) and made this piece. [I then] asked the venerated grand senior Mr. Xingweng to review and comment on it. Your brotherly junior Dongshan Dong Bangda.

Collector's inscription:

Mr. Jimen and I are from the same hometown and associated with the same societies, and like me, he also resides in the old capital city, where we have remained friendly with each other for over thirty years. [He] is skilled in calligraphy and painting and possesses remarkable ability in collecting. I myself am also fond of acquiring the art works left by the past scholar artists in our Zhejiang region. On one occasion, I showed him the landscape painting of Dong Wenque from Fuyang. We unrolled the scroll, together admiring it, which received high praise [from him]. Any object's best destiny is to find its befitting place and the bestowed owner as a keepsake. I therefore bring over this piece and make it a present in order to commemorate our mutual appreciation in all art works of ink and brush.

On the third day of the third lunar month in the year dinghai (1947).

Remarked after returning from viewing the blooming flowers in the mountains

Tuigu, [your brotherly junior] Zhou Zhaoxiang.

LITERATURE: Yilin yuekan, no. 72 (Beijing: Art World Monthly Journal, December 1935), p 2.

Yilin yuekan (Art World Monthly) was launched in 1930. It was originally published three times a month and was therefore called Yilin xunkan. It was sponsored and managed by The Chinese Artists' Association, with the aim of promoting art and presenting materials of artistic significance and value. Due to its professional editorial work and the quality of the selection process for its publication, the journal was well received. The last issue was printed in 1942, with a total of 118 volumes.

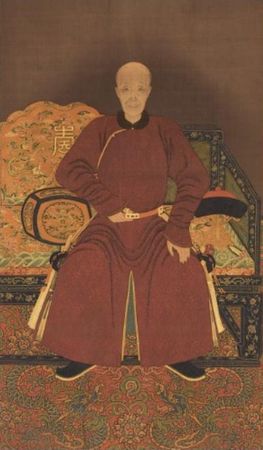

The painter of Seated Portrait of a Prince in Casual Wear remains unknown, but there is no doubt that the extremely finely and gracefully portrayed gentleman was from the imperial lineage (lot 40, est. $90/120,000). The painting is particularly notable for the level of detail with which the artist has depicted the rug and lacquered throne in the painting.

Anonymous (17th-18th century), Seated Portrait of a Prince in Casual Wear. Photo: Sotheby's

ink and color on silk, hanging scroll; 185.5 by 109.3 cm. 73 by 43 in. Estimate 90,000-120,000 USD

NOTE: Imperial portraits constitute a major category of court paintings. They can be sub-categorized into formal commemorative portraits and informal portraits, based on the costumes worn by the sitter. Most portraits are unsigned. Despite the difference in the degree of formality, imperial portraits are all painted in fine detail and rely on costumes, accessories, and background setting to indicate the sitter's status within the imperial family. The portraitists used light ink to outline the bone structure and features of their subjects, followed by layers of light brownish color to render skin color. The early Qing court portraits were clearly influenced by the Bochen School, epitomized by the late-Ming figure painter Zeng Jing (1568-1650). In the mid-Qing, Western oil painting techniques were introduced into the court by European artists, including Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), Jean Denis Attirent (1702 -1768), and their followers. Beginning at this time, a hybrid style developed, characterized by an increased emphasis on chiaroscuro, and a decrease in relying primarily on ink contour lines to render the faces.

Based on this assessment, the present painting probably dates from the early Qing dynasty, that is, the 17th or early 18th century. The subject, who appears to be around seventy years old, is seated in a graceful pose, and exudes a self-absorbed, scholarly elegance--kind, yet stately. Sitting squarely on the gold-decorated lacquer throne, he wears an informal fur-trimmed winter robe of reddish brown satin with swastika pattern, tied with a yellow-gold colored belt. From the belt hang embroidered pouches, a knife, an ivory incense holder, and other accouterments. Based on the Illustrations to the Ceremonial Objects of the Qing, only the emperor's sons, princes of first rank, and imperial family members could wear yellow-gold belts, whereas distant relatives of imperial family wore red belts. The sitter's gold belt thus confirms his princely status.

The black-lacquered throne is inlaid in gold with interlocking branches of flowers and running dragons. It sits on a carpet decorated with twin dragons chasing a pearl design. The throne cover and cushion are tailored from yardage of a gold yellow semi-formal court robe and formal surcoat for an imperial prince of first rank. According to the Collected Regulations & Precedents of the Qing, the emperor's sons are to wear yellow robes decorated with nine mang dragons, bordered by flat gold leaf. The robes for imperial princes of the first and second ranks are governed by the same regulation, except that the color of the ground fabric can only be blue or blue-black. In addition to the large roundels of front-facing five-clawed and side-facing mang dragons, the throne cover and cushion are also decorated with bats, auspicious clouds, a shou character in seal script, and a shallow border of lishui (standing water pattern), all finely woven. The overall design, together with the swastika pattern on the sitter's robe, emblematic of longevity, suggests that the work was intended to be used in a birthday celebration befitting the status of an imperial prince of the first rank.

Although the collections of the Palace Museum in Beijing and the Freer-Sackler Museum in Washington D.C. include many Imperial portraits, depictions of interior scenes with dragon carpets are extremely rare. In the Palace Museum there is one hanging scroll, Portrait of the Emperor Kangxi Writing Calligraphy that depicts a dragon carpet.

The sale also includes two exquisite paintings of Daoist and Buddhist subject matter: Portraits of Jade Emperor and the Heavenly Kings (lot 70, est. $60/80,000), and Heavenly Deities of Land and Water (lot 71, est. $5/7,000). Besides the extremely vibrant and vivid brushstrokes and coloring, each painting celebrates its rarity with an inscription and a specific date, the former being commissioned by one of Jiajing emperor’s concubines in 1545, and the latter dedicated to Longshu Temple on Putuo Mountain in 1617, the forty-fifth year of Wanli reign.

Anonymous, Portraits of Jade Emperor and the Heavenly Kings. Photo: Sotheby's

ated the twenty-fourth year of the Jiajing reign (1545), first lunar month and inscribed, 'Princess Jing of the Great Ming dynasty made a vow to paint this piece, on an auspicious day of the first month in the twenty-fourth reign year of Jiajing (1545).' ink and color on silk, framed; 122 by 87.4 cm. 48 by 34 3/4 in. Estimate 60,000-80,000 USD

PROVENANCE:Purchased at Yonghe Gong, Beijing, in 1949 (see original shipping document)

California private collection

NOTE:The inscription on the present painting reads and may be translated as follows:

Jing fei Wen shi faxin hui shi

Jiajing ershisi nian zhengyue jiri

Concubine Jing with the surname Wen sincerely bestowed this painting on the third day of the first lunar month of the 24th year of the Jiajing reign (equivalent to 1545)

This painting presents an image of the Daoist deity Yu Huang (Jade Emperor) with his celestial court. In Daoism, Yu Huang is the ruler of heaven and all the lower realms, including earth and hell. However, in popular belief, Yu Huang was very much seen as the key figure in the pantheon.

For an early depiction of Yu Huang see a stele dated to 527, in the National Museum of Chinese History, Beijing, included in the exhibition Taoism and the Arts of China, the Art Institute of Chicago, 2000, cat. no. 33. He also appears, with his entourage of deities, on a robe in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, included ibid., p. 197, fig.47, with a similar robe in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, mentioned.

The Jiajing emperor was a devout follower and patron of Daoism. During his reign Daoism gained importance with the number of images of the numerous Daoist gods increasing significantly. See a hanging scroll dated to 1542 commissioned by one of Jiajing's concubine's called Shen depicting the deified Daoist hero Marshal Wang, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, published ibid., pl. 88. This suggests that it was a common practice for the emperor's concubines to commission works of this kind with the knowledge that it would meet his approval.

While little is known of Concubine Jing, records show that she was promoted to Guifei before the 60th birthday of Jiajing in 1566, and that she died during Wanli's reign (1573-1619).

Yonghe Gong, where the present painting was purchased, is one of the most important and largest Tibetan Buddhist lamaseries in China, located in the north-east district of Beijing. Built in 1694, during the reign of the Kangxi emperor, it served as the residence for Prince Yinzhen for nearly thirty years before he took the throne as Emperor Yongzheng.

It was made into an imperial lamasery in the ninth year of the Qianlong reign (1744).

Anonymous, Heavenly Deities of Land and Water. Photo: Sotheby's

dated the forty-fifth year of the Wanli reign (1617), titled, and inscribed, 'Dhtarara, Virupaka, Mahabrahman, Lakshmi. In the forty-fifth year of Wanli reign (1617), Monk Jiren accepted this contribution from the devotee Ni Xing. He delivered it to Mount Putuo where the work will enter the permanent collection of Longshu Temple and forever be revered and worshipped.' ink and color on silk, hanging scroll; 188 by 93.9 cm. 74 by 37 in. Estimate 5,000-7,000 USD

NOTE: The inscription on the present painting reads and may be translated as follows:

Wanli sishiwu nian, muyuanseng Jiren

zhuzi xinshi Ni Xing, song Putuo Shan Longshu An

changzhu yongyuan gongfeng.

This painting was dedicated by Monk Jiren, using believer Ni Xing's funds, to Longshu Temple on Putuo Mountain, shing it to be worshipped forever.

The inscription on the top left corner lists the names of four Buddhist deities: the Guardian God of the East, the God of Brahma (Fan Wang), the Guardian God of the West and the God of Virtue.

The present hanging scroll belongs to a special group of Buddhist images that were made for use in the Water-and-Land Ritual (Shuilu zhai), a rite developed for the salvation of all the deceased. This ritual, commonly practiced by Buddhist worshippers, intended to establish merit (gong) for both the living and the souls of the dead in the netherworld so that they can eventually reach incarnation and ascend to the celestial realms. While a number of important Ming period hanging scrolls of this type are known, those bearing a date and a dedicatory inscription are extremely rare to find in private hands.

Compare an earlier hanging scroll painted with the Masters of Professions and Arts, one of a set of 130 images created for the Water-and-Land rite, in the collection of the Shanxi Provincial Museum, Taiyuan, illustrated in New History of World Art, Toyo hen, vol. 8, Tokyo, 1999, pl. 16; and another painting made for the same ritual, attributed to the Wanli period (c. 1600), depicting the Lady of the Highest Primordial (Shangyuan furen) and the Empress of Earth (Houtu) in the collection of Musee Guimet, Paris, included in the exhibition Taoism and the Arts of China, the Art Institute of Chicago, 2000, cat. no. 97.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F79%2F119589%2F129687802_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F64%2F119589%2F129455644_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F75%2F53%2F119589%2F129451230_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F65%2F52%2F119589%2F129430833_o.png)