Evening fine art sale from the Collection of Elizabeth Taylor achieves $21.8 million

LONDON.- The three top works of Impressionist and Modern art from the storied Collection of Elizabeth Taylor fetched a combined £13,787,750 ($21,784,645 /€16,572,876) at Christie’sLondon Tuesday evening, more than doubling their pre-sale low estimate of £6.2 million. An additional 35 works from the film star’s fine art collection will be offered for sale February 8 as part of Christie’s continuing sales series devoted to Impressionist and Modern Art. Further results for the Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale will be announced at the close of the sale.

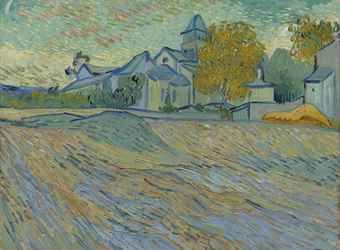

At Tuesday’s sale, Miss Taylor’s Van Gogh, entitled Vue de l’asile et de la Chappelle de Saint-Rémy, fetched the top price of the group at £10,121,250 ($15,991,575 /€12,165,743). The luminous landscape, painted in the turquoise and ochre hues of early autumn, is a view of the asylum where the artist spent his last months. Elizabeth Taylor’s father, the art dealer Francis Taylor, had purchased the painting on her behalf at auction in 1963 for £92,000. Up until her death in March of 2011, the painting had hung in the living room of Miss Taylor’s home in Bel Air, CA.

In the saleroom on Tuesday evening, bidding for the Van Gogh opened at £3 million and was immediately pursued by multiple clients in the room and on phone. It was sold after four minutes of competitive bidding to an anonymous client on the phone.

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy, oil on canvas, 17¾ x 23¾ in. (45.1 x 60.4 cm.). Painted in Saint-Rémy in Autumn 1889. photo: Christie's Images Ltd., 2012

Provenance: Theo van Gogh, Paris.

Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, Paris.

Paul Cassirer, Berlin, by whom acquired from the above on 20 February 1907.

Margarete Mauthner, Berlin, by whom acquired from the above in May 1907.

With Galerie Marcel Goldschmidt & Co., Frankfurt-am-Main & Berlin.

Alfred Wolf, Stuttgart, Lintal, Switzerland and Buenos Aires, by whom acquired from the above after 1928; his sale, Sotheby's, London, 24 April 1963, lot 6.

Acquired at the above sale by Francis Taylor on behalf of his daughter, Elizabeth Taylor.

The Collection of Elizabeth Taylor

Literature: (Possibly) Letter of Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 7 December 1889 (see note).

J.B. de la Faille, L'oeuvre de Vincent van Gogh, Catalogue raisonné, vol. II, Paris & Brussels, 1929, no. 803 (illustrated).

Scherjon & J. de Gruyter, Vincent van Gogh's Great Period: Arles, Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise (Complete Catalogue), Amsterdam, 1937, no. 208.

J.B. de la Faille, Vincent van Gogh, Paris, 1939, no. 791, p. 540 (illustrated; dated and located 'Auvers. June 1890.').

(Possibly) V.M. van Gogh, ed., The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh, vol. III, London, 1958, no. 618, p. 238.

P. Leprohon, Tel fut van Gogh, Paris, 1964, p. 418.

J.B. de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, Amsterdam, 1970, no. 803, pp. 305 & 643 (illustrated p. 305; titled 'View of the Church of Labbeville near Auvers' and dated and located 'Auvers end June 1890').

P. Lecaldano, L'Opera pittorica completa di Van Gogh, da Arles à Auvers, vol. II, Milan, 1977, no. 850, p. 231 (illustrated).

J. Rewald, Post-Impressionism, From Van Gogh to Gauguin, New York, 1978, p. 339 (illustrated).

J. Hulsker, The Complete Van Gogh, Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, New York, 1980, no. 2124, p. 483 (illustrated; dated and located 'Auvers end June 1890').

W. Feilchenfeldt, Vincent van Gogh & Paul Cassirer, Berlin, The Reception of Van Gogh in Germany from 1901 to 1914, Zwolle, 1988, p. 122 (illustrated).

I.F. Walther & R. Metzger, Vincent van Gogh, Sämtliche Gemälde, vol. II, Cologne, 1989 (illustrated p. 558).

S. de Vries-Evans, The Impressionists Revealed, Masterpieces from Private Collections, London, 1992, p. 105 (illustrated).

L. Jansen, H. Luijten & N. Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh, The Letters, The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, vol. V, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1889-1890, London, 2009, letter no. 824, p. 156.

Exhibited: Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Vincent van Gogh, July - August 1905, no. 165 (titled 'Dorpsgezicht in den herfst').

Hamburg, Galerie Paul Cassirer, I. Ausstellung, Vincent van Gogh, September - October 1905, no. 44 (titled 'Herbstlandschaft (Provence)'); this

exhibition later travelled to Dresden, Ernst Arnold Gallery, November 1905; Berlin, Galerie Paul Cassirer, December 1905.

Bremen, Kunstverein, Internationale Kunstausstellung, February - April 1906, no. 94 (titled 'Dorf im Herbst').

Berlin, Galerie Paul Cassirer, Vincent van Gogh, May - June 1914, no. 114 (titled 'Dorf im Herbst').

Berlin, Kronprinzenpalais, Nationalgalerie, Van Gogh - Matisse, 1921.

Berlin, Galerie Paul Cassirer, Vincent van Gogh, January - March 1928, no. 88.

Buenos Aires, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, De Manet a nuestros días: expósicion de pintura francesa, July 1949.

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers, November 1986 - March 1987, no. 36 (illustrated).

Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, Monet to Matisse: A Century of Art in France from Southern California Collections, September - November 1991.

Notes: Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy is an historic painting by Vincent van Gogh, encapsulating his original and unique vision. This luminous picture was included, under titles referring to it as an autumn landscape, in several of the most important early exhibitions of Van Gogh's work, groundbreaking shows which were instrumental in the formation of his posthumous reputation. This includes the 1905 retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam largely comprising the pictures that Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, the widow of Vincent's brother Theo, had inherited. This picture also featured in several of the exhibitions organised by Paul Cassirer in Germany which themselves had a profound influence on the esteem in which Van Gogh's work would come to be held. With its bright colours, with the field bathed in turquoise and ochre which contrasts with the warm yellows and browns of the hay and autumnal foliage, this picture breathes with the atmosphere of the season. At the same time, the long, streaking brushstrokes that make up the field, the darting, shorter marks that comprise the sky and the effervescent, near-Pointillist depiction of the leaves of the main tree contrast with the solidity of the buildings to create an image that buzzes with a discreet energy, pulling the viewer's eyes hither and thither, harnessing that pulsing sense of life that underlies the greatest of Vincent's paintings from the highpoint that came only shortly before the tragically premature end of his life.

In his first edition of the catalogue raisonné of Van Gogh's paintings, printed in 1928, Jacob Baart de la Faille ascribed this picture a later date, placing it in the period that the artist spent at Auvers; however, in his own manuscripts for the revised 1970 edition that was published eleven years after his death having been completed by a committee headed by A.M. Hammacher, it is noted that he had now ascribed a date of October-November 1889. While the committee insisted that the picture showed the church at Labbeville, a small hamlet outside Auvers, John Rewald demonstrated, with photographic evidence, that it in fact shows the chapel of Saint Paul-de-Mausole, as De la Faille's own manuscript stated (see J. Rewald, Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin, New York, 1978, p. 339). This picture therefore dates from one of the absolute highpoints of Vincent's legendary career, when he painted a string of masterpieces, many of which now hang on the walls of some of the most celebrated museum collections in the world.

Rewald and De la Faille's dating has now been adopted by a wide range of people, having been emphatically argued for by Ronald Pickvance in the catalogue to the exhibition he curated at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1986-87, Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers. There, pointing out that this is clearly, as the early exhibition titles agree, an autumn view, he explains that this picture shows the view of the asylum in which Vincent spent his voluntary confinement by Saint-Rémy from the enclosed wheatfield which would feature in some of his most celebrated pictures from the period (see R. Pickvance, Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers, exh. cat., New York, 1986, pp. 152-53). This dating has been adopted in the recent edition of the artist's complete letters, where it is speculated that Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy may have been one of the 'autumn studies' among the dozen paintings that he sent to his brother Theo, writing, 'Yesterday I sent three packets by parcel post containing studies which I hope you'll receive in good order' (Van Gogh, letter 824 to Theo, 7 December 1889, L. Jansen, H. Luijten & N. Bakker, eds., op. cit., vol. V, London, 2009, p. 156).

Vincent had moved to the asylum on 8 May 1889 at Saint Paul-de-Mausole, following a now-famous psychological episode that had led to his being placed under guard in the hospital at Arles. It was in Arles, where Vincent had famously intended to create a School of the South alongside his friend and fellow painter Paul Gauguin, that during a moment of crisis he had appeared insane, mutilating his own ear and terrifying some of the population, who petitioned for his removal. The asylum at Saint Paul - still a centre for mental health to this day, having been founded by three laymen over two centuries ago in an ancient religious compound nationalised under Napoleon - provided a perfect means of allowing Vincent to stay in the South while under observation. During his confinement, the enclosed wheatfield from which Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy would have been painted had provided great solace to Van Gogh, as it was visible from his own room in the asylum, as he told his brother shortly after his arrival there: 'Through the iron-barred window I can make out a square of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective in the manner of Van Goyen, above which in the morning I see the sun rise in its glory' (Van Gogh, letter 776 to Theo, 23 May 1889, ibid., p. 22).

The several images he produced of a reaper in the wheat field were painted from memory from the perspective of his window, as he was not allowed to paint in his room but instead in a studio in another part of the building. By contrast, Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy is one of the few pictures painted out of doors from within his beloved field, alongside another work now in the Indianapolis Museum of Art which was created during the same period and in a similar position, but facing in a different direction, towards the Alpilles, the mountains that featured in several of his pictures of the time. With its orientation, Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy provides a unique view of the asylum and its buildings that includes the Romanesque tower; in his other pictures from Saint Paul-de-Mausole, for instance Parc de l'hôpital de Saint Paul, he showed other views from within the tree-filled garden, or park, which lay on the other side of the buildings. Nowhere else did he depict the complex in its entirety, making this landscape all the more unique a testimony of this crucial period of his life.

Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy dates from the autumn after Vincent's recovery from an attack he had suffered in the summer while in confinement there, an episode that had shattered some of his hopes of a cure. On his first arrival, he had been confined to his quarters, but had gradually been allowed more and more freedom to wander around the area painting, usually under guard. After his attack during his time at Saint Paul, though, he had once more been confined and unable to paint. Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy dates from the period after his recuperation, and clearly captures a sense of the release and joy that he felt, once more able to work out of doors and immersed within nature, and perhaps also increasingly coming to terms with his own condition. Now, in the autumn of that year, surrounded by the warm glow of the seasonal change, Vincent plunged himself back into his work with vigour after the relative inactivity which had lasted for over a month. He wrote to Theo around the time that this picture was painted: 'I'll tell you that we're having some superb autumn days, and that I'm taking advantage of them' (Van Gogh, letter 808 to Theo, 5 October 1889, ibid., p. 113).

In Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy, the incandescent palette of some of his Arles works has given way to a more complex, sophisticated use of colour, revealing a development that Vincent himself would discuss in his letters to Theo around this time. 'What I dream of in my best moments aren't so much dazzling colour effects as the half-tones once again,' he explained in September that year. 'But in these half-tones what choice and what quality!' (Van Gogh, letter 800 to Theo, 5 & 6 September 1889, ibid., p. 88). In part, this was a reaction to the pictures by Delacroix that Vincent had seen in the Musée Fabre in Montpellier. Following the example of his artistic hero, he cooled his palette somewhat, yet it remained electric compared to the works of his contemporaries. This is evidenced by the similarity in the tones of this landscape and his self-portrait from the period, itself breathing with autumnal feeling, now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Despite his protestations to the contrary, Vincent captured the clarity of light of the South, which had been one of the key reasons he had moved to Arles and which lent such a brilliance to the landscape there, making his pictures all the more transcendent as he conveyed the mystery and wonder of existence on an almost religious level through the depiction of the world and people around him. It was in part contemplating a move towards the North, towards his brother in Paris and his wider family in his native Netherlands, that he wrote to Theo discussing the importance of the light quality there: 'perhaps my journey into the south will bear fruit however, because the difference of the stronger light, the blue sky, that teaches one to see, and then above all and even only when one sees that for a long time' (Van Gogh, letter 800 to Theo, 5 & 6 September 1889, ibid., p. 82). In his following letter, he expanded upon this:

'My dear brother, you know that I came to the south and threw myself into work for a thousand reasons. To want to see another light, to believe that looking at nature under a brighter sky can give us a more accurate idea of the Japanese way of feeling and drawing. Wanting, finally, to see the stronger sun, because one feels that without knowing it one couldn't understand the paintings of Delacroix from the point of view of execution, technique, and because one feels that the colours of the prism are veiled in mist in the north' (Van Gogh, letter 801 to Theo, 10 September 1889, ibid., p. 89).

Looking at Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy, that strong sun remains clear in the crisp light that emanates from this canvas. At the same time, the landscape itself appears to thrum with energy, the patterns of the field creating a heaving pattern, a rhythmic rise and fall of diagonal brushstrokes that give a sense of swelling forms. It was during his time at Saint Paul that many of the so-called distortions that characterised Vincent's works came to the fore. While in Arles he had harnessed the power of colour, it was now, in the asylum, that he gained his mastery over form. The subjective manner in which Vincent did this may in part have been from his growing acceptance of his own condition. During his attacks of mental illness, Vincent would suffer hallucinations and other imaginary phenomena and frequently harmed himself and his surroundings. Now, embedded within an asylum and surrounded by other people with psychoses who all looked out for each other, Vincent increasingly came to terms with the nature of his own illness, seeing that others suffered similar, or indeed worse, conditions. The idea that the visible world could melt and alter before his eyes, that his own sight could be altered by his illness, appears to have influenced views such as Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy, which became ever more subjective.

It is no coincidence, then, that it was during this time that Vincent began to garner greater acclaim for his work. Despite being in relative isolation, especially from the hubbub of the Parisian art scene, his pictures were becoming increasingly well known. Those that were stored by Theo at Père Tanguy's were examined by an increasing stream of visitors; one of his pictures was even purchased, often considered to be the only lifetime sale he made. However, his pictures were increasingly dispersed, as he gave them away and also made many exchanges, a factor that allows one to see the esteem in which his fellow artists held his work and which has in part resulted in the strong collection of pictures by those contemporaries held by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. During the period that Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémywas painted, Van Gogh also featured in an article published by the Dutch painter Joseph Jacob Isaäcson discussing the Dutch artistic contributions to the Paris World Fair that year: 'Who interprets for us in form and colour the mighty life, the great life once more becoming aware of itself in this nineteenth century? I know of one, a solitary pioneer, he stands alone struggling in the deep night, his name, Vincent, is for posterity' (J.J. Isaäcson, quoted in J. Hulsker, The New Complete Van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, Amsterdam, 1996, p. 418). It was also during this time that he was invited to exhibit alongside the avant- garde artists of Les XX in Brussels. When this exhibition took place the following year, Vincent's pictures would cause enough controversy that his friend Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec would challenge one of his denigrators to a duel.

Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy was an important witness to the increase in Vincent's fame following his death, as it was one of the pictures that was inherited by Theo's wife, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, after her own husband had died less than a year after his brother. Once those pictures had been shipped to her in Holland, her house became a focal point for those interested in Vincent's trailblazing work, and she became an active custodian and promoter of her brother-in-law's pictures, allowing them to be exhibited and indeed sold, increasing their exposure. This reached a new level in 1905 with the vast retrospective of over 400 pictures that was held at the Stedelijk Museum, an impressive tribute to the Dutch painter. This marked a significant turning point, as it was now that Vincent's work became truly commercial, especially within the pioneering sphere of collectors active then in Germany. Johanna herself, writing to Dr Gachet, whose guest and patient Vincent had been in his final year, wrote to encourage him to visit the retrospective, naming some of the other figures who had travelled internationally to see it:

'Monsieur Meier-Graefe came last Sunday. He was really astonished to see such a large and beautiful exhibition. M. Liebermann and von Schudi [sic] and Cassirer all came from Berlin. It would be such a shame if you were not to see the entire oeuvre' (J. van Gogh-Bonger, quoted in W. Feilchenfeldt, 'Vincent van Gogh - His Collectors and Dealers', pp. 39-46, in Dr R. Dorn, ed.,Van Gogh and the Modern Movement 1890-1914, exh. cat., Essen, 1990, p. 43).

Thus those that made the journey from Berlin included Julius Meier-Graefe, Vincent's biographer who was instrumental in establishing his mythic status especially in Germany, Max Liebermann, the famous German artist, and Hugo von Tschudi, the controversial director of the Nationalgalerie in Berlin whose modern tastes led to his dismissal from that role and his removal to Munich, where he helped to bolster Bavaria's incredible collection of art from that period. Crucially, alongside them was Paul Cassirer, who had already become involved in promoting Vincent's works in Germany and now moved into a different tempo.

While Vincent's works had been shown in Germany as early as 1901, and one of his pictures of a reaper in a wheatfield shown from his window at Saint Paul had become the first to enter a museum collection when it went to the Museum Folkwang in Essen, it was only in 1905 that a significant retrospective was organised. Cassirer, in collaboration with Johanna, organised this show, holding it later in 1905 and touring over 50 works including Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy in his galleries in Hamburg and Berlin, going via the Kunstsalon Ernst Arnold in Dresden. It was there that works such as Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy would find some of their most enthusiastic followers, for the group of four painters who had founded Die Brücke earlier that year, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl, all visited the exhibition. It therefore changed the entire direction of German Expressionism. Die Brücke themselves had an exhibtion at Ernst Arnold's gallery in January the following year. As Max Pechstein, who joined the group the following year, would exclaim, 'Van Gogh was Father to us all!' (Max Pechstein, quoted in J. Lloyd, Vincent van Gogh and Expressionism, exh. cat., Amsterdam, 2007, p. 11).

Cassirer purchased Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Rémy from Johanna in February 1907; in May, he sold it to Margarete Mauthner, an important figure in the art world who had translated a selection of Vincent's letters into German for an edition produced under Cassirer's own guidance. Mauthner was a friend of many of the leading artistic figures in Germany at that time, and also assembled, despite having modest means, an impressive collection of oils and drawings by Vincent van Gogh, an artist whose repute in her country had relied in part on her own work in translating the letters, which stayed in print for a number of years

Earlier in the sale, a youthful self-portrait by Edgar Degas (1834-1917) sold for £713,250 ($1,126,935 / € 857,327) and a large-scale landscape by Claude Pissarro (1830-1903) entitled Pommiers à Éragny realized £2,953,250 ($4,666,135 /€ 3,549,807). All three works were prominently featured in the global tour of highlights from the Collection of Elizabeth Taylor, which reached New York and London last fall. In December 2011, Christie’s New York sold Miss Taylor’s exquisite collections of jewelry, fashion, decorative arts and memorabilia in a four-day marathon auction series that totaled $156.8 million and set multiple new auction records.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Autoportrait, stamped with the signature 'Degas' (Lugt 658; lower left), oil on paper laid down on canvas, 18½ x 12 5/8 in. (47 x 32 cm.). Painted circa 1857-1858. photo: Christie's Images Ltd., 2012

Provenance: The artist's studio, Paris.

Jeanne Fèvre, Nice, by whom acquired from the above; sale, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 12 June 1934, lot 38.

Prince Ali Khan; sale, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 23 May 1957, lot 38.

Acquired at the above sale by Elizabeth Taylor.

The Collection of Elizabeth Taylor

Literature: P. Brame & T. Reff, Degas et son oeuvre, A Supplement, New York, 1984, no. 30, p. 32 (illustrated p. 33).

Exhibited: Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, on loan, 1959-1964 (no. L.2313.59-16).

Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, Monet to Matisse: French art in Southern California collections, June - August 1991, p. 30.

Notes: Painted circa 1857-1858, this skillful and sensitive Autoportrait by Edgar Degas is one of a series of revealing self-portraits the artist executed in his early twenties, at the beginning of his career. Degas captured his own likeness in a range of media during a formative period which began in the 1850s and which lasted until the mid-1860s. Aware of Degas' particular gifts as a portraitist, and with an eye to its commercial viability, his father, in a letter of 1858, encouraged him to persevere with the genre, declaring that, 'portraiture will be one of the finest jewels in your crown' (quoted in P.A. Lemoisne, Degas et son oeuvre, vol. I, Paris, 1946, p. 30). Indeed, not only were Degas' most important early works his self-portraits, a large number of which reside in museum collections, but between 1855 and the mid-1870s portraiture was the most significant genre within his oeuvre.

The present work was executed during Degas' time in Italy where, from July 1856 to April 1859, he spent considerable time visiting museums in Naples, Rome and Florence. Whilst there, he closely studied and relentlessly copied from the Old Masters, painting numerous likenesses of his Italian relatives as well as self-portraits. These works very much display the influence of the Old Masters, particularly that of Rembrandt, whose self-portraits served as a model for Degas' own. Degas' letters from this period reveal that his stay in Italy was marked by loneliness and introspection: 'Myself again. But what do you expect a man on his own and so abandoned to his own devices as I am to say? He has only himself in front of him, sees only himself, and thinks only of himself. He is a great egoist' (Degas, letter to G. Moreau, 7 September 1858, quoted in F. Baumann, 'Degas's Early Self-Portraits', in F. Baumann & M. Karabelnik, eds., Degas Portraits, London, 1994, p. 162).

Self-portraiture allowed the young Degas a means to practise his craft and hone his artistic skill without the need for a model. It also offered the youthful artist a tool for exploring his identity and of scrutinising his relationship to his developing career. As in his self-portrait currently in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Degas has presented himself here in his role as a working artist, clad in his artist's smock and bright violet kerchief. Placing himself against a dark background, and with eyes turned gently towards the viewer, Degas gazes out with an inquiring and somewhat melancholic expression. Soft contre-jour lighting bathes the right side of the artist's face in a warm light, casting the other side into shadow and lending the portrait a romantic aura, something which is also evident in his self-portraits at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles and the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown. The present portrait and that at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute share a freedom in handling that is far removed from the more austere, academic finish of his self-portraits executed just two years before, pre-figuring his association with the Impressionists

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Pommiers à Éragny, signed and dated 'C.Pissarro.94' (lower left), oil on canvas, 23 x 29 in. (60.5 x 74 cm.). Painted in 1894. photo: Christie's Images Ltd., 2012

Provenance: Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris (no. 3149), by whom acquired directly from the artist on 22 November 1894.

Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, by whom acquired from the above on 30 March 1897, until June 1949.

Lazarus Phillips, Montreal.

Sam Salz, New York, by whom acquired from the above in December 1956.

Howard Young Gallery, Chicago, by whom acquired from the above in December 1956.

Elizabeth Taylor, by whom acquired by 1957.

The Collection of Elizabeth Taylor

Literature: L.R. Pissarro & L. Venturi, Camille Pissarro, Son art - son oeuvre, vol. I, Paris, 1939, no. 685, p. 177 (illustrated vol. II, no. 685, pl. 142; dated 'circa 1885').

J. Pissarro & C. Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro, Catalogue critique des peintures, vol. III, Paris, 2005, no. 1028, p. 660 (illustrated).

Exhibited: New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Paintings by Pissarro, February 1917, no. 10.

London, Marlborough Fine Art, Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley, June - July 1955, no. 21.

Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, on loan, 1957 - 1964 (no. L.2313.57-12).

Notes: Painted in 1894, Pommiers à Éragny depicts the orchards and rolling meadows that stretched westwards from Camille Pissarro's property in Éragny-sur-Epte to the neighbouring village of Bazincourt, rising in the distance beyond. Pissarro was enamoured with the open, broad countryside of the Epte valley, describing it as 'a marvel compared to everything else I see' (Pissarro, quoted in J. Pissarro & C. Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Catalogue critique des peintures, vol. I, Paris, 2005, p. 89). He devoted an ambitious series of paintings to capturing and celebrating this bucolic landscape in canvases that explore this motif in different seasons, at different times of the day, and under different weather conditions. Pommiers à Éragny, with its richly textured surface, brilliant luminosity and abundant foliage, is a particularly masterful example from this series which the novelist, playwright and art critic, Georges Lecomte, described rhapsodically: 'Creatures and objects emerge with shining clarity: the air circulates around them; dazzling vapours of gold cast haloes around them. It is the glorious rapture of nature dressed overall' (G. Lecomte, quoted in C. Lloyd, Camille Pissarro, London, 1981, p. 112). For Lecomte, Pissarro had an acute ability to capture 'the essence of the countryside, the spirit of the fields that the melodious symphonies reveal' (ibid.).

In 1884, Pissarro and his family moved to the diminutive hamlet of Éragny-sur-Epte, two hours north of Paris by train, where they rented a house which was, according to Pissarro, 'wonderful and not too dear: a thousand francs with gardens and field' (C. Pissarro, letter to L. Pissarro, 1 March 1884, in J. Rewald, ed., Camille Pissarro: Letters to his son Lucien, New York, 1972, p. 58). Two years before Pommiers à Éragny was executed, the family received financial assistance from the artist Claude Monet, enabling them to purchase the rented house and convert a barn in the garden, which faced towards Bazincourt, into a studio. Pissarro's Éragny has been likened to Monet's Giverny - a rural homestead in the Île-de-France whose countryside the artist immortalised in paint. Whereas Monet transformed his land at Giverny into a garden replete with exotic flowers and plants, Pissarro chose to leave his farm as it was, and painted, as inPommiers à Éragny, georgic landscapes of verdant apple trees, poplars, chestnut trees and fertile fields. Indeed, in an interview of 1892 Pissarro spoke of his wish to express through his canvases 'the true poem of the countryside' - a poetry which, he explained, could be distilled from nature by creating sketches in front of the motif that would subsequently be worked up in successive stages in the studio (C. Pissarro, quoted in R. Thomson, Camille Pissarro: Impressionism, Landscape and Rural Labour, London, 1990, p. 81).

Pommiers à Éragny was painted a number of years after Pissarro had renounced his association with what he came to view as the overly proscriptive Divisionism of Georges Seurat. This canvas, nevertheless, displays the use of luminous colour, particularly the yellow-greens and pinks, which characterises his earlier Neo-Impressionist experiments. A pastel palette keyed to a bright tonality is skillfully balanced in the present painting by the rich greens of the leaves and the grey calligraphic strokes of the apple trees' branches and trunks. Passages of colour, heightened by the addition of flecks of white paint, alternate and divide the landscape into horizontal bands of coloured grasses, whilst greens, pinks and greys knit the composition together. Unlike the more regular brushwork of Pissarro's Neo-Impressionist canvases, the paint application in Pommiers à Éragny is varied and ranges from the rich impasto of the foreground, to the smaller, lively thread-like touches of the apple trees' leaves, to the feathered brushstrokes of the distant foliage. Small dabs of ochre and grey paint, interspersed with the white ground of the canvas which has been allowed to show through, indicate the houses of Bazincourt to the far left in a passage that is reminiscent of the work of Paul Cézanne. The variety of brushstrokes and textures inPommiers à Éragny encapsulates Pissarro's description of Impressionism as an art of 'fullness, suppleness, liberty, spontaneity and freshness' (C. Pissarro, letter to L. Pissarro, 6 September 1888 in Rewald, op. cit., 1972, p. 132.

Pommiers à Éragny has a poetic and graceful rhythm to it which has been achieved through a number of compositional devices. The receding arrangement of apple trees leads the eye into the background and towards the left of the canvas. The more regular allée of trees, placed before the land rises to Bazincourt, subsequently directs the eye back to the centre of the composition and upwards towards the dense foliage in the distance. This abundance of differentiated greenery is punctuated by elegant vertical accents of poplar trees which rhyme with the church steeple, almost wholly hidden by foliage. The curving trunk of the large apple tree in the foreground - a favoured motif of Pissarro's - is repeated in the slightly arched back of a female figure who moves through the landscape. The elevated viewpoint, with its correspondingly high horizon line, absorbs and encloses this figure, suggesting, as a number of critics have noted, a 'harmonious co-existence' between the local people and the land (see J. House, 'Camille Pissarro's idea of unity', in C. Lloyd, ed., Studies on Camille Pissarro, London, 1986, pp. 15-34). This exemplifies Octave Mirbeau's observation of 1892 that in Pissarro's paintings, 'man is always seen in perspective in the vast, terrestrial harmony, like a human plant' (O. Mirbeau, quoted in K. Adler, 'Camille Pissarro: City and Country in the 1890s', in ibid., p. 107). That this figure is articulated with the same brushstrokes as the surrounding landscape, and with flesh tints that repeat those of the surrounding grasses, further illustrates Pissarro's concern with illustrating rural man's 'accord' with nature (see J. House, op. cit., 1986, pp. 15-34).

Late nineteenth century French anarchism, to which Pissarro was fervently committed, idealised rural existence, ascribing to it a social harmony which was held up as a normative model for a society becoming increasingly urbanised and capitalistic. Pommiers à Éragny could be interpreted, therefore, as an illustration of the virtues of a utopian rural existence. Certainly, the lingering effects of the economic recession of the 1880s and the political instabilities of the 1890s of which Pissarro himself was a victim - he went into self-imposed exile in Belgium the summer this painting was executed - are nowhere in evidence in this idyllic landscape. Given Pissarro's insistence that the motif held secondary importance for him, it seems unlikely, however, that this painting can be read as an overt political meditation on anarchist ideology. Rather, Pissarro's concern was to render what he termed his 'sensations' of nature in a canvas that expresses a harmony and unity between mankind and nature, motif and technique. As the artist wrote in 1890, 'I started to understand my sensations, to know what I wanted when I was in my forties, but only vaguely; when I was fifty, that is, in 1880, I had an inkling of the idea of unity, but I could not express it; at sixty, I am starting to see a way of expressing [it]' (C. Pissarro, letter to Esther, 5 May 1890, in J. Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, vol. II,1886-1890, Paris, 1986, p. 349).

Though her jewelry collection was widely heralded as one of the finest private collections ever, few realized the significance of her fine art collection, most of which was displayed only in her home in Bel Air. Her love of fine art began in the home as a child and was encouraged by her father, who had a successful art gallery on London’s Old Bond Street and later, after the family’s move to Hollywood, in the Beverly Hills Hotel. As an adult, Miss Taylor went on to become a devoted admirer of Impressionist and Modern Art in particular. Her acute grasp of 19th and 20th century British and French paintings and drawings led her to assemble an important collection of works.

“The exceptional results for these three masterpieces by Van Gogh, Degas and Pissarro are further evidence of Elizabeth Taylor’s skill and sophistication as a collector,” noted Marc Porter, Chairman of Christie’s Americas. “As the crown jewel of her art collection, we are delighted with the price achieved for Van Gogh’s “Vue de l’asile”, a profoundly beautiful work from one of creative high points of the artist’s career. We look forward to more positive results tomorrow, when we offer the remainder of Miss Taylor’s art collection, including works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Maurice Utrillo, and Kees Van Dongen, as well as an impressive selection of modern British paintings by Augustus John that she inherited from her father.”

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F15%2F52%2F119589%2F129845078_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F25%2F77%2F119589%2F129711337_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F68%2F72%2F119589%2F129601013_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F73%2F119589%2F128782095_o.jpeg)