Islamic & Indian Treasures on sale at Christie’s In April

A gemset rock crystal bottle Mughal India, 17th century and later 5 1/2in. (13.9cm.) Estimate: £100,000-150,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Christie’s introduce a rich offering for Islamic Art Week in April 2012, with five exceptional sales in the King Street and South Kensington salerooms. 2011 saw strong results for the category, particularly for rare pieces of Indian and Turkish origin, illustrating the continuing demand across this market for works of art from the Islamic and Indian worlds. The sale of Art of the Islamic & Indian Worlds on 26 April celebrates the exquisite craftsmanship of works of art produced since the 9th century with a particular focus on later Islamic art. The sale comprises 300 lots expected to realise a total in the region of £7 million. On the same day, A Private Collection donated to benefit the University of Oxfordpresents works of art on paper that will be offered for sale with all proceeds donated to Oxford University. With other dedicated sales for oriental carpets, works on paper and works of art and textiles, this week will offer an extraordinary opportunity for buyers to build a collection or decorate a house.

OTTOMAN TURKISH ART

The sale of Art of the Islamic & Indian Worlds includes a strong array of Ottoman Turkish works of art, including over 20 pieces of Iznik pottery. The most exceptional lot is an impressive large Iznik pottery dish, circa 1585-90, estimated at £80,000 to £120,000 which combines floral and arabesque motifs in vivid colours. It was bought at Christie’s in 1905 from the collection of Louis Huth and has passed by descent to the present owner, it is now offered for the first time in over a century. Other highlights are six Iznik pieces from the late Heinz Kuckei of Berlin (estimates range from £1,000 to £50,000), a dish from the collection of Monique Uzielli (estimate: £40,000-60,000) and a rare Iznik Baluster vase with a unique Chinese shape and design originating from 1550 (estimate: £50,000-70,000).

An impressive and large Iznik pottery dish. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1585-90. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With sloping rim on short foot, the white ground painted in bole-red, cobalt-blue and green with black outlines, with large centraled ground roundel containing palmettes filed with scrolling vine, flanked by sprays of stylised flowerheads and curved saz leaves, the cavetto with cusped palmettes with blue centres, the rim with further palmettes and white edge, the exterior with paired tulips alternating with flowerheads, with three old collection labels on underside of base, three drilled suspension holes to foot, intact: 14¼in. (36.3cm.) diam. Estimate £80,000 - £120,000

Provenance: LLouis Huth, Sold Christie's 25 November 1905

With Durlacher

Ralph Brocklebank, by 1914, Thence by descent

Notes: This dish is an example of both technical and symmetrical aesthetic excellence. It is possible to date this dish through its cusped medallion. Prior to the 1570's cusped medallions of this same form are recorded as containing stylised cloud bands. In 1572 however, we have the first dated set of tiles with cusped medallions which contained scrolling arabesques like the medallion on our dish. A dish previously in the Adda Collection has a medallion containing scrolling arabesques flanked on either side by a symmetrical floral spray which is very similar in design to our dish is dated to circa 1575-80, (Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, London, 1989, fig. 417, p.232).

The last quarter of the 16th Century saw the perfection of the use of the raised bole-red colour that we see employed so masterfully on this dish. The raised red colour was difficult to control and initial efforts produced mixed results. The tiles produced in circa 1561 for the Mosque of Rustem Pasha contained areas of red which were not fully controlled after firing and lost the intensity of their colour, (Walter Denny, The Mosque of Rustem Pasha and the Environment of Change, New York, 1977). The beauty of our dish though comes as a result of the perfected ability to control the contours of the bole-red to produce a precise and wonderful symmetric design. A further dish dated to 1575 which shares this masterful control of bole-red was in the Tevfik Kuyas Collection, (Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, op.cit., fig. 720). The control of the design on our dish is further complemented by the strong full bodied red colour achieved in the glaze. Later attempts with bole-red would produce a glaze of a duller rust colour which does not match the intensity of our dish. Few dishes with bole-red grounds were produced. Due to the technical skill required to achieve the strength of this design, it can be assumed that only the master craftsmen of Iznik were able to produce ceramic vessels of this quality.

An Iznik pottery dish. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1540-50. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With sloping rim on short foot, the interior set on deep cobalt-blue ground with floral designs outlined in black, the central floral medallion with curved white foliage, the cavetto with pairs of flowers alternated with light blue hyacinths with turquoise stems intertwined with stylised tulips, the rim with turquoise floral medallions alternated with daisies and pairs of tulips set between white borders, the exterior with pairs of cobalt-blue tulips alternated with turquoise centred daisies set on white ground, repaired clean break to rim; 13in. (33cm.) diam. Estimate £30,000 - £50,000

Provenance: The Kevorkian Foundation, New York, sold Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, 9th December 1967, lot 176,

Lester Wolfe, sold Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, 14 March 1975, lot 149

Property of the estate of Heinz Kuckei, Berlin.

Notes: As Sultan Süleyman came to the throne in 1520, Iznik ceramic production began an exciting new phase with the addition of turquoise into their previously monochrome colour palette. With this, they made bold step towards the brilliant polychromy for which Iznik later became known.

In its colouring this dish fits into the earlier stage of the transformation into polychromy. The manganese and sage green which enter the palette in the 1530s are not used here, but the black that is introduced around the same time is visible in the outlines of the decoration. Decorative elements that become more standard around 1530, including round vegetal forms, including pomegranates and artichokes with thick trunk-like stems are used freely and with assurance here. These are depicted with an emphasis on axial movement, with swaying tulips emerging from a central roundel which perhaps finds its precedent in the slightly earlier tugrake spiral style (Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik, London, 1989, p.132). While the colour scheme found on this dish is that first used in the 1520s, the colouring continued to be used for another thirty years.

The largest group of comparable dishes is today in the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. One which employs a similar colour palette, and uses the same three-pronged tulip and large pomegranates is dated to circa 1550-55 (inv.no.817, published Maria Queiroz Ribeiro, Iznik Pottery, Lisbon, 1996, no.7, pp.104-05). Another which differs in that it has a cusped rim, but uses similar elements to ours also with strong axial movement is dated circa 1550-60 (inv.no.813, Ribeiro, op.cit., no.24, pp.132-33). As well as sharing with ours elements of the design, all three dishes are decorated with slightly heavy lines and a brilliant strength of the cobalt, bright turquoise and very clear white. The design on ours also relates to one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, formerly in the collection of Benjamin Altman (inv.no.14.40.732). Although later than ours, the design is again very closely comparable (Marie G. Lukens, Guide to the Collections. Islamic Art, New York, 1965, no.54, p.39).

An Iznik pottery dish. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1560. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With deep curved sides and sloping cusped rim on short foot, the white ground decorated with floral spray outlined in black consisting of light blue tulips with bole-red buds interspersed with darker cobalt-blue carnations and daisies, five small stylised cloudbands on upper edge of cavetto, the rim with cobalt-blue and grey-blue wave and rock design, the exterior with cobalt-blue and bole-red alternating cintamani and stylised cloudband, intact; 12¾in. (32.4cm.) diam. Estimate £20,000 - £30,000

Provenance: Formerly Adda Collection, sold Sotheby's London, 9 October 1979, lot 67

Property of the collection of late of Heinz Kuckei, Berlin.

An Iznik pottery dish. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1590. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With sloping rim on short foot, the white ground decorated with a pair of curved cobalt-blue sazleaves and floral spray of bole-red tulips, carnations, with emerald-green foliage, the rim with stylised wave and rock motif, the exterior decorated with alternating circular and floral sprays, intact; 12in. (30.3cm.) diam. Estimate £10,000 - £15,000

Property of the collection of late of Heinz Kuckei, Berlin.

An Iznik pottery tankard. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1590. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Of cylindrical form with slightly flaring rim and angular handle, painted in bole-red, cobalt-blue and green with curved saz leaves, tulips and carnations within borders of cusped arches on blue ground above and below, intact; 7¾in. (19.8cm.) high. Estimate £7,000 - £10,000

Property of the collection of late of Heinz Kuckei, Berlin.

An Iznik pottery dish. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1600. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With sloping sides on short foot, decorated with central sage-green and cobalt-blue curved sazleaf surrounded by large bole-red carnations, tulips and stylised hyacinths with sage-green foliage set on white ground, the rim with stylised wave and rock design, the exterior with cobalt-blue and sage-green geometric shapes, intact; 11 5/8in. (30.5cm.) diam. Estimate £2,500 - £3,500

Property of the collection of late of Heinz Kuckei, Berlin.

An Iznik pottery dish. Ottoman Turkey, circa 1570.. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With cusped sloping rim on short foot, the white ground painted in cobalt-blue, green and bole-red in fine black outline with an asymmetrical floral spray composed of tulips, carnations and hyacinths, the top edge of the cavetto with small cloudbands, the rim with stylised wave and rock pattern, the exterior with alternating paired tulips and flowerheads, intact; 13¾in. (35cm.) diam. Estimate £40,000 - £60,000

Property of the estate of Mrs. Monique Uzielli

Notes: The gentle swaying movement of the flowers represented on this dish indicate the influence of more naturalistic designs favoured by Kara Memi, the chief painter at the Ottoman court in the later part of the 16th Century. He favoured floral arrangements which were often described as 'blowing in the wind' for their sense of flow and movement. For a discussion on Kara Memi and his influence on Iznik designs see Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, London, 1989, chapter XIX, p.222-3. A further dish with a similar flowing design, held in the Omer M. Koc collection, also shares a striking rich dark-green glaze, (Hulya Bilgi, Dance of Fire: Iznik tiles and Ceramics in the Sadberk Hanim Museum and Omer M. Koc Collections, Istanbul, 2009, fig. 54, p. 132). From around 1570 onwards this rich dark green was gradually phased out by a lighter emerald-green glaze. The first recorded use of emerald-green with bole-red dates to 1566-7 and is found on tiles on the portico of the tomb of Sultan Suleyman. A very similar dish dated to 1570-75 was sold in these Rooms, 22 April 1981, lot 331, published in Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, op.cit. fig. 398, p.227.

A rare Iznik pottery lantern jar, Ottoman, Turkey, circa 1540. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Of cylindrical form with rounded shoulder and base, the cylindrical neck slightly flaring, the white ground decorated in pale grey-blue with scrolling tendrils issuing flowerheads, a similar meander around the mouth between radiating simple bands, intact; 11 3/8in. (28.6cm.) high. Estimate £50,000 - £70,000

Notes: Yuan and Ming porcelains were exported to the Muslim world in some quantity for centuries and by the 15th century collections were formed in the Islamic capitals of Tabriz and Cairo. When these cities were absorbed into the Ottoman Empire in 1514 and 1517, Chinese wares made their way into the Topkapi Palace collections and from the 1520s onwards Iznik potters began directly imitating them using the great Yuan and early Ming porcelains of the 14th and 15th centuries as their inspiration.

This inspiration is clearly manifested in the elegant scrolling meandering design on this jar, which is closely based on early Ming models, particularly those of the Xuande period (1426-35, see for example R. Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul, London, 1986, nos.600- 603, pp.512-13). As well as the design, the slightly greyish blue colour used without shading but contained within a dark outline is also drawn from Chinese blue and white porcelain. This colour appeared at on Chinese wares at times when they were forced to use local cobalt rather than imported sources - something which didn't happen during the early fifteenth century which is a period noted for the consistently rich blue of its porcelain. The decoration of this jar is thus the product of inspiration drawn from different periods of Chinese production.

Other Iznik vessels decorated with similar scrolls, lotus flowers and pointed leaves joined in a continuous meander are known. Dishes so-decorated, are found in the Hetjens Museum, Düsseldorf (Islamische Keramik, exhibition catalogue, Düseldorf, 1973, nos.311 and 313, pp.216-17); in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Edwin Binney and Walter B. Denny, Turkish Treasures from the Collection of Edwin Binney 3rd, Portland, Oregon, 1979, Ceramic 3, pp.206-07); the Istanbul Archeological Museum, Istanbul (Esin Atil, The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificnet, Washington D.C., 1987, p.248, no.170); the Ömer M. Koç Collection (Hülya Bilgi, Dance of Fire, exhibition catalogue, Istanbul, 2009, no.15, pp.72-73); and the Gulbenkian Collection (Maria Queiroz Ribeiro, Iznik Pottery, Lisbon, 1996, no.26, pp.136-37). An example with very strong blue cobalt blue, and dated slightly earlier, to circa 1535, sold in these Rooms 21 June 2000, lot 48, More recently another, with colours more similar to ours, dated 1560-80, was sold on 15 October 2002, lot 370.

All of the vessels listed above however are dishes; the most extraordinary feature of ours is the form. Only two other comparables are known - a slightly earlier example with a straighter foot, dated circa 1510-15 that is in a private French collection (Frédéric Hitzel, Turkophilia Revealed, exhibition catalogue, 2011, p.36) and one of slightly stouter form and decorated in polychrome in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is loosely dated to the 16th-17th century (inv. no. 17.190.824). Although other Iznik jars are known, they are usually of a baluster form with a cylindrical neck - a number are illustrated in a miniature of a fruit seller's shop in theBahâristân of Jami copied in Istanbul between 1595 and 1603 (Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby,Iznik, London, 1989, fig.9, p.44). Another miniature from the Surnâme of Murad III (circa 1582), also illustrated in Atasoy and Raby, provides evidence for a diversity in the types of jars produced by the kilns of Iznik. As well as the more standard forms that are shown on and next to the potter's wheel, there is a row of vessels behind amongst which is one jar of cylindrical form, similar to that of the familiar Iznik tankards but without a handle (Atasoy and Raby,op.cit., fig.42, p.53). This may represent a jar of our type.

It is possible that our jar was modeled after a European apothecary jar, or albarello. However it dosen't have the waisted body of a normal albarello and it seems likely that the shape here also finds its precedents in China. The form in some ways relates to Chinese 'lantern jars', early versions of which almost always have Islamic-inspired lattice decoration and were thus presumably for the export market. One of these is in the Palace Museum in Beijing which is dated to the Ming dynasty to the reign of Yongle (1403-24, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum - 34 - Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (1), Hong Kong, 2000, no.43, p.45). Another is in the Al-Sabah Collection (Giovanni Curatola, Art from the Islamic Civilization from the Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait, Italy, 2010, no. 199, p.215). Although there it is suggested that it was possibly made for Mamluk Egypt or Syria, it certainly seems possible and indeed likely that similar wares entered the Ottoman world, and inspired the experimental potters of Iznik.

Other Turkish highlights include a number of Qur’ans and calligraphy, such as a Qur’an from Ottoman Turkey, signed Muhammad Al-Wasfi, dated AH 1245/1829-30 AD (estimate: £7,000-10,000).

Quran Ottoman Turkey signed Mehmet al-vasfi dated ah 1245, 1829-30. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Arabic manuscript on paper, 291ff. plus two fly-leaves, each folio with 15ll. of elegant naskh, gold verse markers, gold sura headings, red and black ruled borders, large gilt and polychrome floral marginal medallions marking points in the text, colophon with gilt and polychrome illumination, opening bifolio with scrolling floral gilt and polychrome illumination and large floral header, in original maroon stamped and gilded morocco binding with flap; Text panel 4 x 2¼in. (10.2 x 5.7cm.); folio 7 x 4½in. (7.8 x 11.4cm.). Estimate £7,000 - £10,000

Notes: Kebecizade Mehmed Vasfi Efendi received his license or ijaza in 1767. He worked for many years as a calligraphy teacher and the future Ottoman Sultans Mustafa IV (r. 1779-1808) and Sultan Mahmud II (r.1808-1839) counted as his students. He is even known to have given Prince Mahmud his license. He is also remarkable for the fact that he often wrote the dedication texts of the licenses in Ottoman Turkish rather than the customary Arabic. This Qur'an is dated to AH 1245 which is just two years before Kebecizade passed away in Muharram 1247 June-July 1831. For a qit'a also by Kebecizade see M. Ugur Derman, Eternal Letters from the Abdul Rahman Al Owais Collection of Islamic Calligraphy, Sharjah, 2009, p. 157

INDIAN ART

Indian art is strongly represented in the sale, notably with a superb Mughal section which includes an exceptional jade-hilted dagger with the original blade. Decorated with gold inlay and encrusted with emeralds and rubies, it originates from early 17th century central or northern India (estimate: £100,000-150,000. A gemset rock crystal bottle is another Mughal treasure from the 17th century, decorated with gold and gemstones (estimate: £100,000-150,000 ). Other Indian objects include a gun from 1832 given by Ranjit Singh, the “Lion of the Punjab” (estimate: £20,000-30,000) and a 19thcentury Sikh battle flag (estimate: £15,000-25,000).

A fine gem-set jade hilted dagger. Central or northern India, first quarter of 17th century. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

The forged and carved slightly recurved watered-steel double-edged blade with armour-piercing point and raised medial ridge leading to raised cusped forte, the hilt of two celadon jade grip panels which extend to bifurcate at the pommel to a pair of upright ears, a gold engraved band between them, inset with quatrefoil emeralds and oval rubies, the jade inlaid with a gold floral trellis set with rubies and diamonds with a pair of addorsed birds on either side of the pommel, the gold quillons set with rubies with central floral medallion extending through ruby inset bands to rounded terminals at either end set with large emeralds, in very good condition, the later associated scabbard with gilt copper locket and chape; 14 7/8in. (37.8cm.) long. Estimate £100,000 - £150,000

Notes: There are numerous representations of the Emperor Jahangir wearing elaborately jewel-encrusted daggers of almost identical shape to our dagger. A miniature dated to circa 1630 from the Kevorkian Album held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. 55.121.10.19v), depicts Jahangir wearing a dagger which also has a very distinct split pommel like our own dagger, meeting his father the Emperor Akbar wearing a more traditional triangular katar, (Stuart Cary Welch, Annemarie Schimmel, Marie L. Sweitochowski and Wheeler M. Thackston, The Emperors' Album: Images of Mughal India, New York, 1987, no. 11, pp. 100-1). A pen and Ink portrait of Jahangir by Balchand which sold in these Rooms, 7 April 2011, lot 258, also depicts the Emperor with a dagger with a split pommel tucked into his belt. A futher miniature depicting Jahangir in this sale, (lot 20) also illustrates him wearing a dagger of the same type. The form of this dagger has been labeled as a kard in an Ottoman or Safavid context, but is ultimately European in origin, (Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, 'The Jewelled Objects of Hindustan', Jewellery Studies, Vol. X, London, 2004, p. 24). A long tradition of exchanging highly ornamented daggers as diplomatic gifts existed between Safavid Iran and Mughal India, which is probably how this dagger form was introduced to Jahangir's court, (Susan Stronge, 'Imperial Gifts at the Court of Hindustan', in Linda Komaroff ed., Gifts of the Sultan: The Arts of Giving at the Islamic Courts, Los Angeles, 2011, p. 171). A slightly less luxurious bone-hilted jewel inset dagger of almost identical form in the Freer Gallery of Art is actually inscribed with the name of Jahangir, further confirming the Imperial associations of daggers of this form, (inv.F.1958.15.a-b; Melikian-Chirvani, op.cit, fig. 20, p. 25).

The form of this dagger might be European in origin but the mastery of the setting of the rubies and emeralds is a wonderful example of Indian craftsmanship. A jewel encrusted dagger in the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, dated to the reign of Jahangir, also has quillons with a fish-scale inset ruby pattern extending to large inset emerald insets on both terminals similar to our own dagger, (inv. 1984.332; Maryam D. Ekhtiar, Priscilla P. Soucek, Sheila R. Canby and Navina Najat Haidar ed. Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2011, no. 255, p. 365). Both our dagger and the Metropolitan Museum example have comparable very fine details carved into the gold settings surrounding the stones, suggesting that they are very likely to be contemporaneous. Our dagger however, unlike the Metropolitan Museum example, still retains its original blade. An emerald and ruby inset jade-hilted dagger also attributed to early 17th Century Mughal India in the al-Sabah collection, is decorated with pairs of birds and scrolling flowering vine similar to our own dagger, (inv. LNS 75 HS; Manuel Keene and Salam Kaoukji, Treasury of the World: Jewelled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals, London, 2001, no.2.10, p.34). This design of birds and flowers is thought to be Persian in origin. The flow of the inset scrolling flowering vine on the jade hilt of our dagger exemplifies a particularly Mughal imperial flare for naturalism. The combination of the European form and the technical excellence of our dagger is great example of the international and multi-cultural flavor of Jahangir's court. It is a great testament to the ability of the Mughal court to absorb and adapt originally foreign forms and combine them with exceptional local Indian craftsmanship to produce unique and treasured luxury objects.

A gemset rock crystal bottle Mughal India, 17th century and later 5 1/2in. (13.9cm.) Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

With spherical body, slightly widening cylindrical neck and flared foot, the body and neck each decorated with a gold painted resin lattice of lozenges, the intersections gemset with turquoises, blistar pearls and garnets, between the lozenges further stones issuing two curving tendrils with leaf terminals, a band of inlaid turquoise around the mouth, partially reinlaid, small restoration to mouth; 5½in. (13.9cm.) high. Estimate: £100,000-150,000.

Notes: This remarkable flask is an impressive example of rare jewel inlaid rock crystal items from the Imperial Mughal court. The form of this flask, known as a surahi, is paralleled in a richly jewel-encrusted jade example dating to the reign of Jahangir (r. 1605-1627), from the Clive of India Treasures sold in these Rooms, 27 April 2004, lot 156,and now in the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar.

In terms of construction, our rock-crystal example is quite remarkable. The two halves of the spherical body are held together by the gold and jewel encrusted 'cage'. This highly sophisticated technique is paralleled in a smaller mango-shaped flask in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York which is also dated to the mid 17th century,and which shares very similar decoration with the present bottle (inv. 1993.18, illustrated in Maryam D. Ekhtiar, Priscilla P. Soucek, Sheila R. Canby and Navina Najat Haidar, Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 257, pp. 367-68). This construction method allowed the craftsmen to carve very fine and, in the case of our flask, elegantly symmetrical halves, which could be fused together to create wonderfully balanced objects.

The drawing of the lattice surrounding our flask is very similar in to a further Mango-shaped bottle dated to the 17th Century in the David Collection, (inv. 35/1980, illustrated in in K. von Folsach, Art from the World of Islam in the David Collection, Copenhagen 2001, no. 370, p. 238). Each of these vessels has a wonderfully fluid scrolling lattice issuing curved leaves and is studded with hardstone centred palmettes. They are both exemplary of the Mughal flare for natural shapes which was prevalent at the imperial court in the 17th Century. It is probable that both our bottle and the David Collection mango-shaped flask have been re-inlaid, but in India and a considerable length of time ago, probably in the same workshop.

A Mughal rock-crystal cup in the al-Sabah Collection attributed to the late 16th or early 17th Century, like our flask, is also inset with turquoises and pearls, although there forming the design on the interior of the bowl while the exterior is set with emeralds and rubies (Inv. LNS 208 HS; Manuel Keene and Salam Kaoukji, Treasury of the World: Jewelled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals, London, 2001, fig. 2.6, p. 33). This confirms a continuity of materials used between the cup in the al-Sabah collection and our flask. This is an unusually large inset rock crystal vessel from the Mughal court, clearly showing the elegant design that was so typical of the period of the early Mughal rulers.

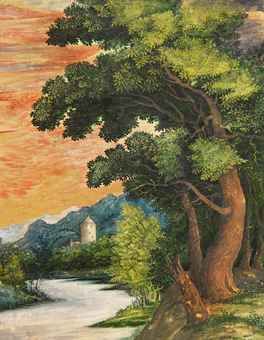

The Indian miniature section is led by a rediscovered folio of great beauty from the St Petersburg Muraqqa, which is amongst the most spectacular albums of miniatures known.Ladies by a river, dating from circa 1680, is estimated £30,000-50,000. The miniature depicts ladies bathing in a river with detailed Rheinland landscape of a forest, a castle and a dramatic sky. A calligraphy from the same Muraqqa is priced at £8,000-12,000.

A gathering at sunset. The miniature MughalIndia, circa 1680, the borders signed Muhammad Hadi,Iran, dated AH 1170/1756-57 AD. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Gouache heightened with gold on paper, a wide river runs through a green and leafy landscape, on its banks women bathe and wash their clothes whilst others visit a senior member of the Gorakhpanthi Nath community seated in the bottom right corner, the river with rocky island topped with a a European style building, further buildings on the horizon beneath the dusky sky, laid down between minor pink borders with gold illumination on wide navy borders decorated with elegant gold interlacing vine issuing palmettes and leaves, miniature extended, partially stuck down on board; Miniature 7 x 11 7/8in. (17.7 x 30.1cm.); folio 12 1/8 x 18 3/8in. (30.8 x 46.6cm.). Estimate £30,000 - £50,000

A folio from the St. Petersburg Muraqqa

Notes: It is believed that the Indian paintings from the album now known as the St. Petersburg Muraqqa' were taken to Iran by Nadir Shah following his sack of Delhi in 1739. Whilst there, the folios were all given new borders and almost all backed by panels of calligraphy by the master calligrapher Mir Imad (see the following lot). The album was obtained in 1909 by the Russian Aulic Councillor Ostrogradsky from Jews in Tehran who had in turn purchased it from the Royal Library after which it was presented to the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg (Francesca von Habsburg et al., The St. Petersburg Muraqqa', Lugano, 1996, p.20). At that stage the manuscript contained exactly 100 leaves. In 1912 the Metropolitan Museum purchased one leaf which appears to be the earliest provenance on any of the leaves outside Russia. In 1931 six of the best folios of all were sold to the Freer Gallery.

Of the paintings known from the album, most were produced between the early 16th and the end of the 17th centuries, although there are a few works from half a century either side of this period. Most are Mughal - including a few that were intended for the Jahangirnama and thePadshahnama, although there are two early 17th century Deccani works and twenty Persian paintings, mostly of the late 17th century. Half of the paintings postdate Shah Jahan's rule (1628-58) (Elaine Wright, Muraqqa. Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library, Virginia, 2008, p.575).

The very distinctive pink and orange sky of our miniature is close to that of a one that depicts "A Pahlaavan's Initiation Ceremony" from the album which is attributed to around 1720 (Abolala Soudavar, Art of the Persian Courts, New York, 1992, no.131b, p.324). The basic conceit however relates more closely to one entitled "A Late Mughal Outing" from the album formerly in the collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan (Von Habsburg, op.cit., pl.234, pp.125-26). That miniature depicts a group of ladies bathing on the banks of a river, whilst a smaller group of women sit beyond them - talking, playing music and smoking a nargileh. Like our miniature that one shows a similar blend of classical Mughal features and those clearly influenced by European prints. The ladies in the foreground of that miniature seem to be influenced by a Western model. Similarly the landscapes of both miniatures, with the winding rivers, the gently swaying trees and in our case distinctive buildings - some even surmounted by crosses - could be lifted straight from a European print. Indeed buildings perched on a rocky hilltop in an engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) entitled The Seamonster, offered in these Rooms, 28 March 2012, lot 3, bear close resemblance to those in our miniature, and may provide a possible prototype. The small cluster of ladies who sit on the banks beyond the bathers in the Aga Khan miniature, retain a Mughal formality and with their gold-edged sheer veils and distinctive features, relate very closely to those found on ours. That miniature, which is attributed to circa 1680, is inscribed Mahmud (although in the lower left hand corner, an area that appears to have been extended).

For a calligraphic folio from the St. Petersburg Muraqqaq as well as a short discussion on the borders of both pages, please see the following lot.

A calligraphic exercise (mashq). The calligraphy attributable to 'Imad al-Hassani, SafavidIran, late 16th/early 17th century, the borders signed MuhammadHadi,Iran, dated AH 1171/1757-58 AD. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Pen and ink on marbled paper heightened with gold, the folio covered in elegant black Persiannasta'liq written in various directions, a separate panel above with a single line of blacknasta'liq in a cloud reserved against gold ground decorated with dense light blue scrolls, the two panels laid down between red minor borders with elegant gold floral illumination on wide navy borders decorated with gold scrolling vine issuing palmettes and leaves; Calligraphic panel 9 3/8 x 6 7/8in. (23.7 x 17.5cm.); folio 18¼ x 11¾in. (46.1 x 29.9cm.). Estimate £8,000 - £12,000

Notes: Three artists were known to work on the decoration and composition of the album in the mid-18th century - Muhammad Hadi, Muhammad Baqir and Muhammad Sadiq. Most of the work of decorating the album was done by Muhammad Hadi, the artist who signed both the gold illuminated margins of this mashq, and those of the miniature of the preceding lot, which are dated AH 1170 and 1171 (1756-57 and 1757-58 AD) respectively. In his discussion on the compilation and decoration of the album, Anatol Ivanov writes that Hadi only decorated the margins around the calligraphic specimens (Francesca von Habsburg et al., The St. Petersburg Muraqqa', Lugano, 1996, p.26). Here however the margin that surrounds the miniature is very clearly signed by him. As the album was organized in such a way that miniature faced miniature, and calligraphy faced calligraphy, always with matching margins, it seems likely that a hitherto unpublished miniature with margins by Muhammad Hadi is yet to be discovered.

Although little is known of the life and work of Muhammad Hadi, research done by B.W. Robinson confirms that he was seen in Shiraz on the 10th September 1821 by the English traveller Claudius Rich who described him as a very old man who no longer practiced his art (B.W. Robinson, Persian Miniatures from Collections in the British Isles, 1967, cat.no.94, p.78). It is worth mentioning that he also described him as amongst "the most distinguished artists in Persiapassionately fond of flowers" and that it was "almost impossible to procure a specimen of his pencil. They are bought up at any price by the Persians" (Robinson, op.cit., p.78). If the two Muhammad Hadi's are the same, then he would indeed have been over ninety years old on Rich's sighting, and probably relatively young when he undertook the commission for this album although already with the status to have been invited to take part in such a project (von Habsburg, op.cit., p.27). Diba records him as an illuminator who specialized in floral designs. He is also known to have worked on a number of other works including a qalamadan which was formerly in the Niyavaran Palace Collection and which is dated AH 1148/1735-36 AD and many single leaves of narcissus, carnations and roses (Layla S. Diba, "Persian Painting in the Eighteenth Century", Muqarnas, Vol. VI, p.154).

The St. Petersburg Muraqqa contained calligraphic folios that were the work of only one calligrapher, Mir Imad al-Hasani, and this mashq is therefore easily attributable to him. For a short note on the famous calligrapher, please see lot 15. For a miniature from the St. Petersburg Muraqqa as well as a note on the album from which these folios come, please see the preceding lot.

OTHER HIGHLIGHTS

A great array of other works of art spanning a wide range of geographical areas, materials and time are included in the sale. A leading highlight is an important and rare enameled and gilt glass bottle from 13th century Syria decorated with unique bilingual Arabic and Byzantine Greek inscriptions and applied small animal shapes (£600,000-800,000).

An important enamelled and gilt glass bottle with Byzantine Greek and Arab inscriptions. Late Ayyubid or early Mamluk Syria, late 13th century. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

f circular form with flattened sides, trailed and applied glass with enamelled and gilded decoration on blown glass body, stags and lions interwoven inside a scrolling lattice on sides, the ground with gilded and red enamelled scrolls and depictions of small birds, the top with eight-pointed stellar form, front and back with concentric circular bands of enamel contained between applied bands of glass and punctuated with circular bosses with alternate bands of loose naskhand Byzantine majuscule inscription around a central roundel with falconing figure neck missing, otherwise intact, considerable surface iridescence; 4in. (10.2cm.) high - Estimate £600,000-800,000

Provenance: Acquired by the present owner 2000, formerly European private collection since 1975

Notes: This is a unique survival from mediaeval Syria, an enamelled and gilded glass bottle with both Greek and Arabic inscription and with clear Christian iconography. Both in terms of the iconography and in the techniques it uses it is without parallel in the published corpus of enamelled glass.

Notes: This is a unique survival from mediaeval Syria, an enamelled and gilded glass bottle with both Greek and Arabic inscription and with clear Christian iconography. Both in terms of the iconography and in the techniques it uses it is without parallel in the published corpus of enamelled glass.

FORM: The body of this flask was free-blown to form a rounded shape which then had a kick foot impressed to form the base, and the sides were lightly flattened. This form is very similar to that of the typical Mamluk sprinkler or qumqum such as one now in the museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, made for al-Baba Badr al-Din Muhammad, governor of Qus under Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad (1293-1341) (Abd el-Ra'uf Ali Yousuf, 'Syro-Egyptian glass, pottery and wooden vessels', in Rachel Ward (ed.), Gilded and Enamelled Glass from the Middle East, London, 1998, fig.6.5, pp.23 and 158). The proportions here are slightly different from those of the normal qumqum, with the kick foot making less of an indentation and therefore each side appearing more round than is normally encountered. The form is also related to that of "pilgrim bottles", more frequently found in unglazed pottery, with flattened circular sides and much shorter neck and mouth than the qumqum, (for a typical example please see one sold in these Rooms 10 October 2000, lot 266).

There is a much larger enamelled glass vessel in the British Museum that also takes the form of a pilgrim bottle, in that instance copied more closely from a brass original (Rachel Ward, 'Glass and Brass, Parallels and Puzzles', in Ward, op.cit, pls.9.,6 and 9.8, pp.34, 164 and 165). While the scale on which that bottle is made is completely different, the two vessels share considerable similarities in the arrangement of the designs, a comparison we shall return to.

TECHNIQUE: This flask displays a unique combination of techniques. Each is known separately, but never combined in the same vessel. The basic form has two completely distinct techniques that are used to decorate it. The first to be applied was the trailed and moulded decoration which covers the sides, round onto the shoulder and around the mouth, as well as the simple moulded bands that form the concentric circles and bosses on each face. Much of this applied decoration is the simple application of trails to form the design. The animals however appear to have been moulded before being applied. The modelling is too fine in a number of cases for this to have been worked into the glass once the basic lump of glass that was going to form the animal had been attached to the body. Not content with the technical difficulty of achieving this, the craftsman has executed the whole design on a rounded surface which would have been considerably more difficult than if it had been flat. The final result, of scrolling animal headed vine around a variety of single and paired animals is one that is well attested in Ayyubid art, but less typical of Mamluk.

Once the moulded and trailed decoration had been applied the craftsman painted the background of the shoulder with powdered gold held in suspension and also with powdered glass of various colours which were then fired to form the enamel designs on the surface. These were both in larger blocks of colour on the shoulder and also in finely drawn white and red lines forming outlines and the inscriptions on each face. During this final firing stage there must have been a considerable risk that the vessel would have cracked in the kiln, especially with the very different thicknesses of the glass caused by the applied moulding. The design elements used in this enamelling are very similar to those one finds in Ayyubid and Mamluk enamelled glass, with bichrome curling leaves filling gaps between elements. The colours are more difficult to determine since burial has led to the deterioration of some. The red remains clear, but the number of other colours is not so easy to identify.

INSCRIPTION: There are three bands of inscription on each side. The outermost band in each case is executed in enamel against a white enamel ground. It appears to be Arabic but, although there is considerable variety of letter forms, the inscription is completely illiterate. The middle band is the one that is most difficult of all to decipher. It seems to have been executed in gold script set against a blue enamel ground. The script is Greek uncial but so little is left that it is not possible to say more than that. The inner inscription is also in Greek uncial, but in this case using the same combination of colours and materials as the outer Arabic band. This band is only partially legible, but enough can be made out to be certain that it is literate and that it was at one stage fully comprehensible. It places the vessel clearly within a Christian context especially if one reads the word that follows ???? as ??, a shortened form of "Jesus". This is therefore the first gilded and enamelled vessel to be placed within an eastern Christian, possibly Byzantine context. The famous gilded and enamelled bowl in the Treasury of San Marco, Venice, while generally agreed to be Byzantine, has iconography that owes nothing to Christianity (Ward, op.cit., col.pl.A).

ICONOGRAPHY. In the centre of each side is a small roundel depicting what appears to be a child. Nothing remains of the surface decoration, so it is difficult to be certain, but this would fit with the iconography of Christ Immanuel, where Christ is portrayed as anything from a very young boy to a youth. On one side the figure is holding both arms out in welcome (Matthew 11:28 "come unto me all ye who are heavy laden and I will refresh you"). On the other he is holding a sceptre in one hand with the dove of peace above the other. This latter combination is unusual in icons; it could refer to Christ who is the King but comes in Peace. The form of this small central roundel, applied in relief to the body, is reminiscent of the glass paste medallions with Christian religious themes that have been found throughout the Eastern Mediterranean (Hans Wentzel, 'Das Medallion mit den Hl. Theodor und die Venezianischen Glaspasten im byzantinischen Stil' in Werner Gramberg et al., (eds.),Festschrift für Erich Meyer zum sechzigsten Geburtstag 29 October 1957, Studien zu Werken in den Sammlung des Museums für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, 1959, pp.50-67).

The decoration on the shoulders presents a wonderful combination of Christian and Islamic sources. The central motif on each side is a stag, below which is animal headed vine. Animal headed vine is was particularly used in an Ayyubid context, being found in manuscripts, on metalwork, and on marble capitals (see a capital in the Aga Khan Museum formerly sold in these Rooms 7 October 2008, lot 128; the note gives the reference to many comparable items). The combination however of the two elements on this bottle is probably a reference to the Christian lore about the stag which is the enemy of the serpent. There are many instances of depictions of stags eating serpents, from mosaics in a recently discovered church in Libya, now housed in the Qasr Libya museum, to the opening initial of psalm 41 in the St. Alban's Psalter housed in Hildesheim dating from 1123-1143. The reference is to the psalm itself, which begins "As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God". The reference to eating the serpent is that after doing so the hart or stag becomes particularly thirty for the word of God. Is this a clue to the original content of the bottle? Was it made to contain water of particular sanctity? We know that the two enamelled flasks now in the treasury of St. Stephen's cathedral in Vienna were brought back from the Holy Land containing soil onto which the blood of the Holy Innocents had fallen. They were presented in 1365 to the cathedral by Duke Rudolf IV (Melanie Gibson, "A Syrian Enamelled Wine Flask: Was its owner a Christian or a Muslim?", Association Internationale pour I'Histoire du Verre, annales du 15e congrès 2001, p.192; illustrated in Wardop.cit, pl.25.9, pp.115 and col.pl.E).

The animal combat pairs on the upper shoulders are relatively easy to parallel in an Islamic context, but seem to have a considerably more playful and less bloodthirsty feeling to them than is normal. The image in one particular instance is reminiscent of a kitten with a bird it does not quite know what to do with, rather than a lion ferociously attacking its prey.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: Vessels made using both glass and brass are known that were created within Muslim workshops for Christian patrons in both the Ayyubid and earlier Mamluk periods. Those in bronze are grouped together and discussed by Eva Baer in Ayyubid Metalwork with Christian Images Leiden 1989. A number of glass examples are known, including the Vienna flask noted above, two beakers in the Baltimore Museum of Art (John Carswell, 'The Baltimore Beakers', in Ward, op.cit, pp.61-63), and a recently discovered magnificent bottle now in the Furusiyya Collection (Stefano Carboni, Glass of the Sultans, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2001, cover). While bilingual Latin and Arabic inscriptions are known in a number of bronze vessels this is the first glass vessel to be published that carries inscriptions in a Christian and Arab script, even if the Arabic is illiterate. It is indicative of the frequent interaction between the two communities that was prevalent in Syria in the 13th century.

The very large glass pilgrim flask in the British Museum noted above is very relevant to our understanding of this bottle not just in the shape and its potential use; it too was probably made for a Christian patron. Certainly the only surviving metalwork example of the form on that scale, the Mosul silver inlaid brass canteen in the Freer Gallery, is covered with Christian imagery (Esin Atil, W.T.Chase and Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., 1985, no.17, pp.124-136). A comparison between the British Museum glass pilgrim flask and the present bottle shows a very similar arrangement of the design, especially on the shoulders. The deer on the shoulders of the present bottle are very comparable in scale and prominence to the mounted huntsmen on the British Museum flask. Again it makes one wonder if the two had a similar purpose, which would reinforce the suggestion that our bottle was made for water of a particular importance or sanctity.

ATTRIBUTION: There seems little doubt that our bottle was made in Syria. This is where the techniques found in this bottle were developed. Ayyubid greater Syria is also where animal-headed vine was such a typical decorative motif. This is also the period and place to which, with good reason, most other brass and glass vessels made with Christian imagery are attributed. The very few vessels that have bilingual Latin and Arabic inscriptions are also all attributed to Syria, with the basin made for Elisabeth von Habsburg-Kärnten, the queen-consort of Peter II of Sicily (1337-1342) attributed specifically to Damascus (Europa und der Orient, exhibition catalogue, Berlin, 1989, no, pp.205 and 597). Altogether "the culture of this area in the thirteenth century reflected a remarkably harmonious political and economic modus vivendi between Christians and Muslims" (Ranee A. Katzenstein and Glenn D. Lowry, 'Christian Themes in Thirteenth-Century Islamic Metalwork,Muqarnas, vol.I, New Haven, 1983, p.62).

As for the dating, the similarity with the British Museum pilgrim flask is a good starting point. Although originally dated by Lamm to the mid 13th century this has now been convincingly re-attributed to circa 1330-1350 (Ward, op.cit, pp.30-31). This period also happens to be the one that saw the majority of the bilingual inscriptions in Latin and Arabic known on brass vessels. The animal headed vine is however an earlier, principally Ayyubid, feature, so a period right at the end of or shortly after the end of Ayyubid dominance seems probable, in the late 13th or early 14th century.

There is one final thought, which might just be coincidence. The earliest painter of glasses, (i.e. enameller) to be recorded in Venice, the person who it is suggested brought the technique of enamelling to Venice, is a Greek, mayster Grigorius from Nauplion. He is frequently recorded working in Venice from 1280 until 1288 (Maria Georgopoulou, 'Fine Commodities in the Thirteenth Century Mediterranean, the Genesis of a Common Aesthetic', in Margit Mersch and Ulrike Ritzerfeld (eds.), Lateinisch-griechisch-arabische Begegnungen: Kulturelle Diversität im Mittelmeerraum des Spätmittelalters, Berlin, 2009, p.81). Could there be a connection between mayster Grigorius and the Greek painter of the present bottle?

The metalwork section is led by a large Mamluk basin made of shiny brass for the last important Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, Qansuh al-Ghuri, in the early 16th century (estimate: £40,000-60,000). Contemporaneous with this are two silver inlaid vessels that clearly demonstrate the trade links between Syria and Europe; one even bears an Italian coat of arms (estimates: £15,000-25,000 and £7,000-10,000).

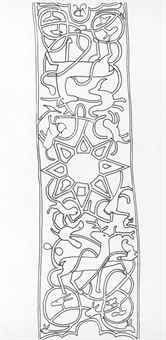

A large late Mamluk brass basin. Syria, period of Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri, 1501-16 AD. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Hammered and engraved brass, with slightly rounded base, inverted sides and wide flaring rim, the exterior engraved with a series of interlaced cartouches containing honorific thuluthinscription, blazons and dense arabesque interlace, floral vine or geometric strapwork, the rim with a wide band of bold flowerheads issuing further arabesques on a ground of scrolls, the interior of the rim with a main band of similar calligraphic cartouches alternated with smaller cusped cartouches containing blazons and flanked by trilobed cartouches containing and surrounded by arabesques, the base of the basin with a central blazon surrounded by roundel containing dense, knotted arabesque, soldered band of old repair between base and sides; 21in. (53.4cm.) diam. at wides. Estimate £40,000-60,000

Notes: The incription in the cartouches around the rim of this basin read, 'izz li-mawlana al-sultan , al-malik al-malik a , al-ashraf qansuh , al-ghawri , 'azza nasrahu, 'Glory to our Lord, the Sultan, the Possessor, al-Malik al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri, may [God] glorify his victory'. Around the body is the inscription, wa al-imam al-a'zam al-malik , sultan al-islam wa al-muslimin , muhyi al-'adl fi al-'alamin , qatil al-kafirin wa al-mushrikin, 'And the Greatest Imam, the King, the Sultan of Islam and Muslims, Reviver of Justice in the Worlds, Slayer of Unbelievers and Polytheists'.

Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghuri (r. 1501-16) was the penultimate Mamluk sultan - his reign marks the finale of Mamluk pious and artistic patronage. He commissioned a great number of buildings and built a commercial and residential quarter in Cairo. Metalwork from the reign Qansuh al-Ghuri is very rare. The Islamic Art Museum in Cairo has three mosque lamps from his madrasa which was founded in AH 909/1503 AD and a dish dated AH 922/1516 AD (all published in Gaston Wiet,Catalogue Général du Musée Arabe du Caire, Cairo, 1932, nos.239, 508 and 3169, pls.XX-XXI, XIX and LVI, pp.28-29, 37-40 and 76-77). The Topkapi has a lamp and the Harari Collection another dish (Wiet, op.cit., no.24).

The form of this basin is familiar: it is found in numerous Mamluk examples - see for example one in the British Museum made circa 1330 for Sultan Nasir al-Din Muhammad (inv.no.51 1-4 1, Esin Atil, Renaissance of Islam, Art of the Mamluks, exhibition catalogue, Washington D.C., 1981, no.26, pp.88-89). The decoration on the other hand is unusual. It relates very closely to that of so called Veneto-Saracenic metalwork, which is characterized by extreme fineness and dense small-scale designs. Combining this distinctive decoration with a classic Mamluk shape, blazons (contained within a lobed rather than the more typical rounded cartouche) and the name of a Mamluk Sultan - the basin provides compelling support for the argument that Veneto-Saracenic was produced in Egypt or Syria, rather than by Muslim craftsmen settled in Venice.

A very closely related basin to ours is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon (donated by the Marquis Arconati-Visconti in 1961, previously in the ancienne collection Raoul Duseigneur, inv.E 538-50, Rémi Labrusse, Islamophilies. L'Europe modern et les arts de l'Islam, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2011, cat.358, p.354). That is said to be inlaid with silver, although no trace is visible in the catalogue image. The Lyon basin bears the name of a seemingly unidentified Abdu 'Abdullah bin al-Wafa'i. Another closely related basin, though of shallower form and without the wide flaring rim, is in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan (inv.1657, published in Doris Behrens-Abouseif, 'Veneto-Saracenic Metalware, a Mamluk Art', Mamluk Studies Review, vol.9, no.2, Chicago, 2005, fig.4, pp.149 and 162). The three basins together are decorated in a style akin to that of conventional Veneto-Saracenic ware, including a number which are European in form. All have the same engraved patterns with a sequence of curved cartouches of alternating format with flowers in the background. In her discussion of the Lyon and the Milan basins, Behrens-Abouseif writes that they could have been produced by the same hand as the a Veneto-Saracenic jug, of very European form, also in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum (inv.1656, Behrens-Abouseif, op.cit., fig.5, pp.149 and 163).

Our bowl is an important addition to this small corpus. None of the vessels mentioned above bear the name of an identified patron. Ours, which has the name of Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri, provides firm evidence that it - as well as the others, both classically Mamluk and those more commonly thought to have been made in Venice - must have been produced under the Mamluk realm rather than further afield.

A Mamluk provenance is supported by contemporaneous elements of architectural embellishment that use similar intricate decorative flourishes to those used on Veneto-Saracenic vessels. The walls between the pendentives of the sabil-maktab of the funerary mosque of Amir Khaybak (1502-21), for instance, are carved with a pattern of dark arabesques that stand out against a lighter grey stone ground and turn through small 'endless-knots' - a decorative feature found both in our bowl and in the wider corpus of Veneto-Saracenic metalwork (Doris Behrens-Abouseif, Cairo of the Mamluks. A History of the Architecture and its Culture, London, 2007, fig.330, p.314). Amir Khayrabak (more commonly known as Khayrabak Bilbay) was recruited by Qaitbay but was appointed governor of Aleppo during al-Ghuri's reign, where he remained until the Ottoman conquest of 1517.

This basin was probably never intended to be inlaid. A bowl and a candlestick, each made for Sultan al-Ashraf Saif al-Din Qaitbay either have no precious metals or otherwise only small silver dots (Atil, op.cit., nos.34-35, pp.100-03). A ewer made for the wife of Qaitbay, now in the British Museum, uses silver sparingly, but the main inscription was left as polished brass (Rachel Ward,Islamic Metalwork, London, 1993, pl.94, p.118). This is generally explained by the world shortage of precious metals at the time, but Atil - using the example of the candlestick made for Qaitbay mentioned above - writes that a new style of decoration was becoming increasingly popular at the time - objects were being incised with a sharp tool and a black bituminous material was being applied to the sunken areas of the background. Familiar also in silver and gold inlaid metalwork, when used alone on brass the bitumen created a feeling of depth, and the practice became predominant in the ensuing years, replacing the technique of inlaid metalwork (Atil,op.cit., p.101). This bowl supports Atil's theory of the lack of inlay representing a new style, rather than economic concern. Bearing the name of a Sultan, it would no doubt have been produced according with the highest qualities and latest fashions.

An important signed and engraved silver-inlaid bowl. Mamluk or post-Mamluk Syria, early 16th century. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Of rounded slightly conical form with flaring rim and extended foot, the sides with silver-inlaid scrolling vine which form a pattern of alternating hanging and suspended palmettes, two of which contain cartouches with elegant naskh inscriptions, set on a ground of engraved tightly scrolling vine, the side of the rim a with band of silver-inlaid scrolling vine, and the top of the rim with a band of silver-inlaid elegant naskh; 6½in. (16.5cm.) diam. Estimate: £15,000-25,000

Notes: The verses on the rim in vernacular Arabic are undeciphered. A suggested reading for the signature cartouches is, bi-rasm muhammad ibn barakat? ibn 'umar?.. al-'ajami

A covered cylindrical box in the collection of the Courtauld Institute of Art displays almost identical decoration to that on our bowl, (inv. O.1966.GP.203., Sylvia Auld, Renaissance Venice, Islam and Mahmud the Kurd. A Metalworking Enigma, 2004, no. 3.2, p. 200). Auld, commenting on the engraved and silver inlaid design of split palmettes on a ground of engraved arabesques common to both vessels, confirms the quality and finesse of the workmanship. She proceeds to attribute this specific design to the workshop of the master craftsman Zain al-Din. The panels on the side of our bowl give us the name of a previously unknown further master craftsman of the same school as Zain al-Din

There has been some debate as to the attribution of items from the group identified as from the workshop of Zain al-Din. Sylvia Auld has suggested that they were produced in an Ottoman context whereas Doris Behrens-Abouseif has argued for a Mamluk provenance, (Doris Behrens-Abouseif, 'Veneto-Saracenic Metalware, a Mamluk Art', in Mamluk Studies Review, vol. IX/2 , Chicago, 2005, p. 148). Crucially, Abouseif pointed to an Arabic inscription in verse on the rim of a comparable signed bowl to our own in the Khalili Collection, (inv. MTW 1542, Behrens-Abouseif, op.cit. fig 15, p. 169). The Arabic vernacular inscriptions on our bowl and on the Khalili bowl confirm that these vessels were produced in the Arabic speaking Mamluk world rather than in the Persian courts of Anatolia or Iran. This bowl therefore forms part of an important and rare group of vessels which confirm the Mamluk origins of these pieces.

A Mamluk silver-inlaid bowl for export. Mamluk Syria, late 15th century. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Of rounded form with small waisted section and slightly flaring rim, the base with engraved central roundel containing interlocking palmettes surrounded by a band of scrolling vine, around this large cusped palmettes in a radial design, all on ground of tight scrolling vine, the sides with four roundels alternating with blazons and scrolling vine set on lattice ground and knotted rosettes, bordered below by a band of silver inlaid psuedo-calligraphy and above and below with bands of scrolling vine, rim with pearl border, old repairs

5 7/8in. (15cm.) diam.

Notes: A slightly larger bowl in the Victoria and Albert Museum is of almost identical form and decoration to our bowl, (inv. 1686-1889, Sylvia Auld, Renaissance Venice, Islam and Mahmud the Kurd. A Metalworking Enigma, 2004, no. 4.1, p. 208), Auld compares the bowl in the Victoria and Albert museum to a basin made for the Mamluk Sultan Qai't Bay (r. 1468-1496), in the Turk ve Islam Eserleri Muzesi (TIEM) in Istanbul, (S. S. Blair and J. Bloom, The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800, New York, 1994, fig. 142, p. 111). Our bowl probably also dates to the late 15th Century, however the European-style blazons engraved and inlaid on the side of this bowl indicate that it was destined for export to Europe.

Highlights from Iran include a remarkable group of evocative and brightly coloured 19thcentury paintings; consisting of a magnificent and impressively detailed portrait of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar by Muhammad Hassan Afshar (estimate: £70,000 -100,000), An equestrian portrait of Sepahsalar by Isma'il Jalayir (estimate: £60,000-80,000) and A court musician playing the kemanche, School of Abu'l Qasim (estimate: £70,000-100,000). Another fascinating Iranian object is a rare and large fragment of carved grey stone schist roundel, illustrating combating animals, from 15th century Timurid Iran (estimate: £200,000-300,000).

Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar Attributable to Muhammad Hassan Afshar, Qajar Iran, mid 19th century. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Oil on canvas, bust-length portrait, Nasir al-Din Shah is depicted sitting on a red-upholstered chair wearing tall black hat with white egret plume and diamond embellishments, grey uniform with blue silk sash and heavily jewelled belt, bazubands, epaulettes and frogging, pinned to his chest are various Qajar medals, a similarly jewelled shamshir lies in his lap, minor areas of repainting to figure, figure cut out and laid down on later background; 46 1/8 x 31in. (117.2 x 78.8cm.). Lot 220. Estimate £70,000 - £100,000

Notes: This portrait is attributable to the Muhammad Hassan Afshar (active 1818-1878). Muhammad Shah's painter laureate, Muhammad Hassan Afshar Urumieh enjoyed an unusually long career spanning the reigns of Fath 'Ali Shah, Muhammad Shah and Nasir al-Din Shah. Well known as a painter of large formal court portraits, his style quickly evolved from a version of the more traditional mode of the court of Fath 'Ali Shah to something more innovative. Influenced in part by grandiose European prototypes that were finding their way into Iran, Muhammad Hassan Afshar rejected the richly patterned and brilliantly coloured aesthetic of his predecessors. He began to use aerial and linear perspective and a greater modelling of form as well as compositions where the subject dominated the front plane of the picture against distant landscapes and open skies (Layla Diba (ed.), Royal Persian Paintings. The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925, exhibition catalogue, New York, 1998, p.211).

In this portrait of Nasir al-Din Shah, the artist has opted for restrained and somber colours. Coloured gemstones in his epaulettes and aigrette have been abandoned for diamonds which create a stark contrast with his dark robes. This is similar to the treatment that Muhammad Hassan Afshar gave a number of portraits that he did of Muhammad Shah, who in turn seems to have inherited this taste for stylish contrast from his father 'Abbas Mirza. An example of a portrait of Muhammad Shah that shows this fashion is in the Louvre (Diba, op.cit., no.67, pp.224-25). The materials used in the various elements of Nasir al-Din Shah's costume in this portrait, are all heavily textured such that they are almost tangible. The treatment of the jewelry, painted with heavy impasto so that the gemstones seem to sparkle - is very typical of the work of Muhammad Hassan Afshar. Similarly, the silk sash that Nasir al-Din wears, where the shine and texture of the material is very visible, relates to that on a painting signed by Muhammad Hassan Afshar and dated 1839-40, formerly in the collection of Joseph Soustiel and exhibited between 25 October to 8 November 1974 (Jean Soustiel, Objets d'art de l'Islam, Paris, 1974, no. 54, pp.42-43).

Although his principle period of royal patronage came under Muhammad Shah, Muhammad Hassan Afshar is also known for paintings of Nasir al-Din Qajar. Indeed B.W. Robinson describes Afshar's most remarkable works as life-size oil paintings of the monarch in the Gulistan Palace Museum, Tehran, in a private Tehrani Collection and in the Chehel Situn, Isfahan (dated AH 1276/1860 AD, B.W. Robinson, Persian Miniature Painting, London, 1967, p.83). Karimzadeh Tabrizi mentions a further image (he does not mention the media) by Muhammad Hassan Afshar depicting the wedding of Nasir al-Din Shah.

An equestrian portrait of Mirza Husayn Khan Moshir al-Dawla Sepahsalar (d. 1881 ad). Inscribed Isma'il Jalayir, Iran, circa 1870. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Oil on canvas, set in a landscape with buildings and mountains on the horizon, Sepahsalar mounted on a parading white horse wears a richly embroidered black coat adorned with numerous military medals, signed in white nasta'liq to the right of the figure, some retouching, in gilt-wood frame with identification panel; 39¾ x 31in. (100.9 x 78.7cm.). Lot 226. Estimate £60,000-80,000)

Property from a Noble Collection

Notes: Mirza Husayn Khan Moshir al-Dawla Sepahsalar (d. 1907) was the Prime Minister under Nasir al-Din Shah between 1871 and 1873. He attempted to implement a number of political reforms during his short mandate. The present portrait depicts Sepahsalar using a composition which emphasizes his rank and his official functions. The inscription to the right of the sitter attributes the painting to Isma'il Jalayir, a painter whose work was characterized by a dream-like, otherworldly quality and who was one of the 'most gifted alumnus' of the Dar al-Funun(R.W. Ferrier (ed.), The Arts of Persia, London, 1989, p.231). The present portrait however, draws indeed on a different aesthetic than that visible on an equestrian portrait of Nasir al-Din shah by Isma'il Jalayir which sold in Christie's, London, 29 April 2003, lot 185. That portrait retains many of the idiosyncratic features of Jalayir's work, while ours displays a much stronger European influence.

An equestrian portrait of 'Ali Quli Mirza I'tizad al-Saltaneh by Ustad Bahram Kirmanshahi, dated 1864, offers a better comparable to the present painting (in a private collection, Layla S. Diba, Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar epoch 1785-1925, New York, 1998, cat. 77, pp.247-48). Although less refined, the portrait of 'Ali Quli Mirza depicts the sitter on horseback in a similar, conventional position which is the same as that visible here. In detail the two are also similar - the horses, whose bodies are depicted with almost photographic accuracy, have similar almost cartoon-like faces with large, slightly coy eyes. Bahram Kirmanshahi is said to have studied academy-style paintings in Russia where he was very probably exposed to Russian and Austrian equestrian portraits which were perceived as conveying strength, intelligence, nobility and authority (Diba, op.cit., p.247). In such portraits the horse is often understood as a metaphor for the people and the rider therefore as the one who controls them. During his mandate as Prime Minister of the Shah, Sepahsalar tried to implement political reforms looking westward to European models. This depiction of him in a typically European style may also well reflect the personal taste of this historically important Persian official.

A court musician playing the kemanche. School of Abu'l Qasim, Qajar Iran, first quarter 19th century. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

Oil on canvas, a young musician wearing a red floral embroidered skirt and jewelled yellow jacket kneels on a floral carpet playing a kemanche, before her a white floral tray with two glasses, very small areas of repainting, unlined, in gilt-wood frame with identification inscription below; 55½ x 31 5/8in. (140.8 x 80.4cm.). Lot 209. Estimate £70,000 - £100,000

Notes: Tony Falk describes Abu'l Qasim as an artist who "possessed great skill and who adopted a very distinct style for his portraits" (S.J.Falk, Qajar Paintings, Persian Oil Paintings of the 18th and 19th Centuries, London, 1972, p.39). B.W. Robinson writes that he may have been a native of Shiraz, working away from the artists at the Tehran court. This would explain why this artist, in spite of his ability, was not employed for court commissions by Fath 'Ali Shah (B.W.Robinson, ' The Court Painters of Fath 'Ali Shah', Eretz-Israel, vol.7, Jerusalem, 1964, p.103). Very few of Abu'l Qasim's works survive. Those that do appear to be from a single series of pictures of which three were formerly in the Amery Collection. Two of them, each signed and dated AH 1231/1816 AD, depict young female musicians, one playing a drum and the other a guitar (Falk,op.cit., nos.19-21). The third is unfortunately is in poor condition and has been considerably reduced. Stylistically they are very close indeed to our painting. Like ours, the two ladies in the Amery paintings sit in a carpeted interior before a balustrade and plain horizon holding their instruments in their hands and with wine on trays before them. Their clothes, like our lady, are heavy with pearls and stones and their long hair curls down their back, but with a feeling of lightness. Falk suggests that the two Amery paintings quite possibly came from the same original canvas (Falk, op.cit., p.40). Another portrait in that collection, which depicts Fath 'Ali Shah sitting on a pearl-studded cushion, was probably originally the centerpiece of the group (Falk, op.cit., no.16).

B.W. Robinson writes that Abu'l Qasim's ladies "attain the utmost degree of bejeweled magnificence and smouldering voluptuousness, and are undoubtedly the most successful surviving representations of the Persian ideal of feminine beauty by an artist of the period" (Robinson, op.cit., p.191). Our lady, as the Amery examples, plays to the Qajar ideals of beauty. These Diba describes as including "joined eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes, puckered lips and flamboyant hairdo" (Layla S. Diba (ed.), Royal Persian Paintings. The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925, exhibition catalogue, 1998, p.207). In her description of a portrait of two harem girls attributed to Mirza Baba, Diba describes them as members of the harem, possibly concubines of the ruler, on the basis that had they been entertainers bought in to the harem to perform, they would not have been wined and dined in the manner portrayed (Diba, op.cit., no.57, pp.206-07).

An impressive animal combat grey schist roundel. Timurid Iran, circa 1430 or earlier. photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2012

The stone carved with a repeating radial design of ferocious lions pouncing on unsuspecting deer, the lions with their teeth sunk into the deer's backs and the deer with their heads raised and turned, stepped border around, losses to edges, mounted on metal stand: 21in. (53.3cm.) diam. at largest. Lot 145 Estimate £200,000-300,000

Provenance: London art market 1976

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F84%2F119589%2F126266259_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F61%2F48%2F119589%2F126266099_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F90%2F75%2F119589%2F122213203_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F96%2F72%2F119589%2F92366388_o.jpg)