A very rare embroidered satin and pearlwork 'Twelve Symbols' Imperial court robe, Jifu, Qing dynasty, Daoguang Period

Lot 3198. A very rare embroidered satin and pearlwork 'Twelve Symbols' Imperial court robe, Jifu, Qing dynasty, Daoguang Period. Estimation 6,000,000-8,000,000 HKD. Lot vendu: 7,820,000 HKD. Photo Sotheby's

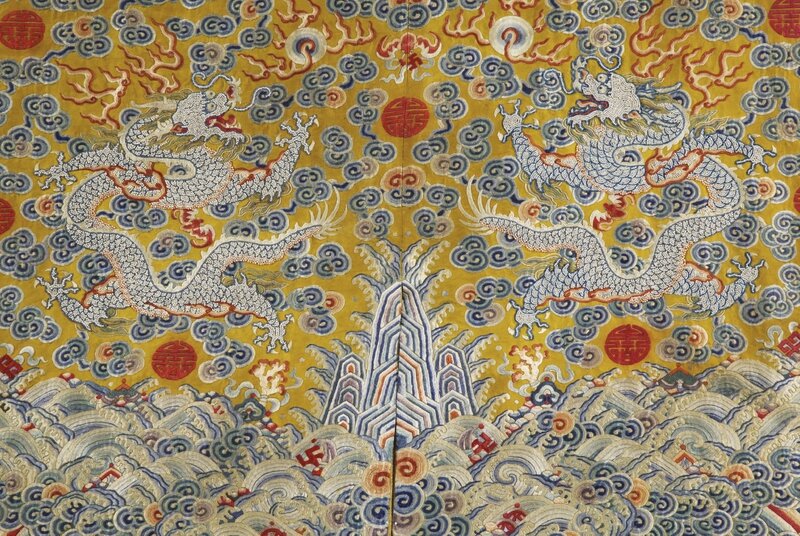

the rich yellow satin ground meticulously worked on the front and back with nine fiveclawed dragons intricately and precisely embroidered with tens of thousands of minute fresh water seed pearls, the dragons in pursuit of embroidered 'flaming pearls', amidst the Twelve Symbols of Imperial Authority: the sun, the moon, mountains, dragon, pheasant, two goblets, pondweed, fire, rice, and axe, stars and the character fu, all among multicoloured cloud scrolls, orange shou medallions, and bats grasping the wan character in their mouths, above rolling and crashing waves above a lishui band, the dark-blue silk forearms left plain, the dark-blue satin horse-hoof cuffs and collar decorated with writhing dragons and bats above waves, with couched gold thread hems, and patterned yellow silk lining; 139 cm., 54 3/4 in.

An Imperial Twelve-Emblem Robe with Seed Pearl Beads. By Fang Hongjun, Associate Researcher, Beijing Palace Museum

Imperial dragon robes (longpao) of the Qing dynasty, also called coloured dress (caifu) and patterned clothes (huayi), fall under the general category of ceremonial dress. They were worn primarily during festive holidays, banquets, and religious sacrifices. For example, the emperor wore a dragon robe on such occasions as the lunar New Year's Day, the emperor's and empress's birthdays, the winter solstice, lunar New Year's Eve, the Plowing Ritual at the Temple of Agriculture, banquets, major weddings, and the Mid-Autumn Festival. At these many occasions the emperor often wore a dragon robe with a ritual robe (gunfu) or by itself.

In many people's minds, a dragon robe has a design of a golden dragon and coloured clouds on a bright-yellow background, but that is not the case. So-called coloured dress and patterned clothes were robes selected for their designs and colours according to the varying needs of the season or festive holiday. On occasion, the emperor would institute a favorite colour for his dragon robe for use on a particular occasion. For example, on 30th January 1756, the eunuch Wang Jinglong conveyed the following imperial instructions of the Qianlong emperor: 'After a bath, the emperor is to wear a greenish-brown, tapestry-weave serving dragon robe lined with black fox. For every lunar New Year's Eve from now on, this is to be the precedent.'1

The emperors' and empresses' dragon robes of the Qing dynasty were of many colours. There were robes of bright yellow, apricot yellow, golden yellow, light brown, ginger yellow, greenish brown, pale pinkish purple, lilac, forest green, light sea green, slate blue, maroon, peach red, pink, bluish white, dark slate blue, rouge red, blue, red, green, dark brown, crimson, brown, purple, tan, etc. On different festive occasions, the prototypical dragon design might be replaced with such auspicious designs as the shou medallion, Han-roof-tile designs, floral roundels, crane roundels, happiness-meeting-happiness designs, five bats circling the shou medallion, ancient cultural treasures, a bountiful grain harvest, accessories of the 'Eight Immortals,' and for robes worn at major weddings, dragons and phoenixes.

Qing Gong ci ('Lyric poetry of the Qing palace') describes an auspicious scene of the time thus: 'The emperor's birthday was celebrated in grand fashion. People referred to ancient court etiquette for the limits set for patterned dress. And they exhaustively reviewed past practices to follow the imperial restrictions. Everywhere spring was bursting forth. Why, even the paintings submitted in defeat.'

The arrangement of the dragons on the dragon robes of the Qing dynasty was based on an expression of 'The Majesty of 9-5' from the Book of Changes. Here '9-5' indicates the position of the line of interest in the hexagram, 9 being the whole, unbroken line, and 5 being the fifth line of the hexagram. 'Qian' is the name of this hexagram. The Qian hexagram presages greatness (yuan), lack of impediments (heng), suitability (li), and steadfastness (zhen). 'The Majesty of 9-5' signifies imperial authority. When we look at a proper imperial Qing dynasty dragon robe, with a design of dragons, we see that there is a en face dragon on each shoulder, on the chest, and on the back, and there are two flying dragons on the front lower hem and again on the back lower hem. There is also a flying dragon under the front panel. As a result of this arrangement, when viewed from the front or back, the robe always presents five dragons, and when the robe's main dragons are added together, there are nine dragons. Qing dragon robes thus give concrete expression to the ancient notion of 'The Majesty of 9-5.' At the same time, this expression of cultural background shows how thoroughly the minority Manchu people, in their control of the government, could assimilate the meanings of China's broad and profound traditional culture.

The dragon is a symbol of the Chinese people. What is a dragon, and how does it differ from a python [in this context, 'python' refers to a four-clawed dragon, not the snake]? How does a dragon robe differ from a python robe (mangpao)? Most people accept the theory that a dragon has five claws and a python has four claws. According to Qing regulations, when the emperor gave an official a dragon robe or other article with five-clawed dragons, the official had to use a sewing needle to remove the fifth claw of each dragon, thus converting a dragon robe into a python robe (see Qinding Daqing huidian [Imperially authorized regulations of the great Qing dynasty], issued by the Yongzheng court). More accurately, the distinction between dragon and python was primarily between different ranks of individuals and only secondarily between different patterns and colours. When an article of clothing with the same pattern was worn by individuals of different rank, it was called by a distinctly separate name. For example, during the Qing dynasty, the emperor and princes both wore ceremonial robes ornamented with nine five-clawed dragons. Only the emperor's ceremonial robes could be called dragon robes, and the robes worn by princes could only be called python robes, though imperial dragon robes were sometimes ornamented with the 'Twelve Imperial Emblems' and were coloured a bright yellow to mark the distinction. It was not the pattern or colour that determined whether a robe was a dragon robe or a python robe. For instance, during the Qing dynasty, the bright-yellow ceremonial robes of the empress dowager, the empress, and imperial honored consorts were not ornamented with the 'Twelve Imperial Emblems', yet they were still called 'dragon robes.' The ceremonial robes of imperial honored consorts, consorts, and concubines, though they lacked the twelve imperial emblems, might be coloured golden yellow or greenish brown, just like the emperor's, and be called dragon robes. During the Qing dynasty, the only ceremonial robes for men called 'dragon robes' were those of the emperor, and the only ceremonial robes for women called 'dragon robes' were those of imperial female relatives: the empress dowager, the empress, imperial honored consorts, honored consorts, consorts, and concubines. All other ceremonial robes were called python robes, even those of princes, dukes, aristocrats, and members of the royal family. Thus, the only criterion for distinguishing a dragon robe from a python robe was the status and rank of the wearer.

Early in the Qing period, while the ceremonial robes of the emperor and his concubines differed in shape and style for men and women, they shared the same patterns: they were all eight-roundel dragon robes, over which was worn an eight-roundel dragon surcoat. With the development of the dress code during the Qing dynasty, the eight-roundel pattern was given over to the court women and became a pattern unique to the imperial concubines. Though imperial dragon robes were categorized as ceremonial dress in the Qing dress code, in practice they were used as both formal ritual dress and less formal ceremonial dress, that is, as dress for both sacrifices and celebrations. Especially when the emperor personally conducted a grand ceremony or sacrifice, he often wore a dragon robe with a court robe. For example, on the day prior to an imperial sacrifice at the Temple of the Soil and Grain, Temple of the Earth, or Temple of Heaven, the emperor, wearing a yellow or blue dragon robe, would review the votive tablets to put himself in the right frame of mind so that the sacrifice of the next day would go smoothly. This is precisely what was meant in the ancient Chinese system of rites when it was said, 'To perform the rites, first clear the mind' (Chunqiu fanlu [Luxuriant dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals], 'Guan zhi xiang Tian [Official regulations take Heaven as image]').

This Daoguang-period lined dragon robe, with pearl beads and a design of dragons and clouds embroidered on bright-yellow fine silk, has the following style: a circular collar, a wide curving lapel fastened on the right, horse-hoof sleeves, five gilt-bronze répoussé floral buttons, and a skirt with four slits. The interior is lined with light coloured silk damask with a subtle cloud-and-phoenix pattern. The inside of the collar has a seal impression of burnt-red seal wax.

On the ground of bright-yellow silk, this robe makes use of such embroidery techniques as dense beadwork, flat stitches, couching, interlink stitches, and seed stitches. Pearl beads and coloured thread were used to embroider densely stitched pearl dragons, seas, and cliff banks, amid which are the 'Twelve Imperial Emblems', coloured clouds, bats grasping wan swastika symbols (symbolizing everlasting great happiness), and the shou medallions. From the robe's dragons, ruyi clouds, and use of colour, we can see that this robe has a style typical of the Daoguang (1821-1850) and Xianfeng (1851-1861) periods of the Qing dynasty. The tailor—by using natural freshwater seed pearls, colour transitions from unsaturated to saturated, ingenious colour contrasts and combinations, and fine, smooth embroidery — has produced a garment that is both eye-catching and finely decorated.

The 'Twelve Imperial Emblems' have a long history. They first appeared on the ritual apparel of premodern emperors, princes, feudal lords, ministers, and high officials. The twelve imperial emblems are the sun, the moon, the stars, mountains, dragons, axes, fu, flames, pheasants, ritual cups, aquatic grass, and grains of rice. Shangshu ('The Book of Documents', prior to the third century BCE), 'Yi Ji' (Bo Yi and Hou Ji), states, 'I want to see the emblems of the ancients—the sun, the moon, the stars, mountains, dragons, and pheasants—painted, and the ritual vessels, aquatic grass, flames, rice grains, axes, and fu finely embroidered and displayed in the five colours on garments. Please understand.'2 China's ancient ritual dress code has its roots in the system of temple sacrifice. According to Chunqiu fanlu yizheng (Luxuriant dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals, annotated), 'All clothes arose to cover and warm the body. But dyeing them in the five colours and embellishing them with designs is of no benefit to the skin or blood.'3 Again according to Chunqiu fanlu yizheng, 'It would not do for the Duke of Yan to appear at court in dress embellished with the emblems that appear on the emperor's garments.'4

The biography of Jia Yi (200–168 BCE) says, 'In the past, only the emperor and empress wore such clothes, in order to make sacrifices in the temples and to fast.'5 Later in history, rulers of every age would use the 'Twelve Emblems' for different purposes, giving them new associations and explications, until finally they became the exclusive providence of rulers in the court code and an external symbol of rulers' aggregation of sovereign authority. This trend appeared most prominently in Qing emperors' apparel, where the institution of ritual caps and garments was thoroughly abandoned. By this time, the 'Twelve Emblems' could embellish not only the ritual apparel used exclusively in sacrifices. They appeared on Qing emperors' formal wear (court robes and ritual apparel) and ceremonial dress (dragon robes). At the same time, they could no longer be used by feudal princes, ministers, and high officials. Truly, it was a case of 'the noble man making his status apparent through his dress.'6

During the Qing dynasty, use of the 'Twelve Emblems' began in the Yongzheng period (1723–1735), when use was limited to seven emblems, and became established in the Qianlong period (1736–1795), when use was extended to all 'Twelve Emblems.' In the Tenth lunar Month of 1748 the Qianlong emperor issued an edict stating, 'I note that precedents concerning the painting of mountains and dragons have been handed down in the history of Yu, and that juyi and yuzhai [two types of ancient ladies' garments] were made according to the colour code and stipulations for Zhou officers' dress. In laying out the prescriptions for members of the court when they carry out my orders for sacrifices, it is very important that they follow propriety and related matters. Though we have already regulated these matters and followed them for over a hundred years, it still would be good to draw up diagrams to show how to follow the model. From my court crown, court dress, ordinary crown, and ceremonial dress to the court caps and garments of princes, dukes, major officials, and officers above the ninth rank; from the court crowns and court dress of the empress dowager, empress, imperial honored consorts, consorts, and concubines to the court caps and court apparel of prince consorts and court ladies—matters concerning such restrictions shall be brought to a committee consisting of Wang Youdun, Wang Zhale, and A Dai. They will discuss and consider matters in detail; determine regulations; follow models; divide Manchus, Han, and Mongols into named colours; draw diagrams for viewing; and present matters for my decision, that we may leave a model for posterity.'7 Late in the Qing dynasty, owing to a weakening of governing institutions, the court code was not strictly adhered to, and some court ladies and princes wore five, seven, or even twelve emblems on their apparel, giving rise to lapses in following the Qing code.

Among Qing royal garments that have come down to us, embroidered garments with seed pearl beads frequently met with imperial reproaches and were severely prohibited. In the Tenth lunar Month of 1776, the Qianlong emperor decreed, 'Recently people have tended to be extravagant in their gifts and have lost sincerity of intention. Yesterday I happened to see some items that entered our offices from the house of Xiong Xuepeng. Among them were such items as an embroidered python robe with seed pearl beads . . . These items cost considerable labor and expense and yet are unfit for use. I strongly condemned such gifts. . . Afterward, none of the provincial governors presented gifts again to the palace other than local tribute. As a group, princes, dukes, high-ranking officials, and Inner-Court Hanlin academicians at the capital should also follow this precept. I hereby use this general edict to inform them.'8 Just as the emperor commanded, among items held in the Qing palaces, we now find not many embroidered dragon robes with seed pearl beads. Those that we do have are mainly from the Kangxi (1662–1722), Yongzheng (1723–1735), and Qianlong (1736–1795) reigns, as well as from the Guangxu reign (1875–1908). From the Qianlong emperor's edict and by looking at the surface materials used in this Daoguang lined dragon robe with seed pearl beads and a design of dragons and clouds embroidered on bright-yellow fine silk, it is not difficult to discover that this dragon robe uses silk from the Lu River area of Shanxi. Hence, we can surmise that this robe is similar in style and craftsmanship to the embroidered robe with pearl beads presented by Xiong Xuepeng. It probably came from the governor of Shanxi.

Though this robe, because of its age, shows some damage on the button loops, it is difficult to conceal that this Daoguang embroidered robe with pearl beads is a rare find—a fact that makes it all the more worthy of appreciation as a fine piece of work.

Notes

1. No. 1 History Archive of China, 'Apparel Archive,' lunar year 1755.

2. Shangshu zhengyi, 'Yi Ji.' In Shisanjing zhushu (Thirteen Classics, Annotated), vol. 5, p. 141. Zhejiang: Zhejiang

Guji Chubanshe, 1998.

3. Chunqiu fanlu yizheng, vol. 8, sec. 27 'Duzhi' (Institutions), p. 232. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1992.

4. Chunqiu fanlu yizheng, vol. 7, sec. 26 'Fuzhi' (Dress codes), p. 224.

5. Chunqiu fanlu yizheng, vol. 7, sec. 26 'Fuzhi,' p. 224.

6. Chunqiu fanlu yizheng, vol. 6, sec. 14 'Fuzhi xiang' (Aspects of the dress code), p. 154.

7. Qing Gaozong Chun huangdi shilu (Imperial veritable records of the Qing emperor Qianlong and empress Chun),

lunar Tenth Month 1748 part 2, vol. 327, pp. 403–404. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1986.

8. Qing Gaozong Chun huangdi shilu, vol. 1018, p. 657

Sotheby's. Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art. Hong Kong | 04 avr. 2012 www.sothebys.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_af8bb4_telechargement-6.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_b6c4a6_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_65a1d8_telechargement-31.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240331%2Fob_7209d9_117-1.jpg)