Sotheby's London Arts of the Islamic World Sale presents an exceptional range of works

Model of the Dome of the Rock, Dr Conrad Schick, Jerusalem 1872-3. Estimate: £250,000-£300,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

LONDON.- Sotheby’s London announced that its Arts of the Islamic World sale on 24th April 2013 will bring to the market one of the strongest ever offerings of paintings, manuscripts, textiles, ceramics and weapons, spanning thirteen centuries of Islamic history. Many of the works in the sale are of museum quality and have rarely or never before been seen at auction. Highlights of the sale include a unique, intricately detailed model of The Dome of the Rock, one of the most sacred sites in Islam (est. £250,000-£300,000*), and an extremely rare intact concertina-form album of Persian miniatures and calligraphy from the 16th-19th centuries (est. £50,000-70,000). In total the sale of 304 lots is expected to achieve in excess of £6.9 million.

Benedict Carter, Sotheby’s Director and Head of Auction Sales of Islamic Art, London, said: “In response to the growing international demand for arts of the Islamic world, for our forthcoming sale we have succeeded in sourcing a broad range of exceptional pieces that are of a remarkably high calibre. The selection to be offered will be of great appeal to the extremely discerning collectors in this field - those who are specifically seeking items of Islamic significance, and those who acquire in this field purely out of appreciation for the exquisite craftsmanship and rarity of the paintings, manuscripts, textiles, ceramics and weapons that the sale comprises.”

PAINTINGS

Of special interest in the sale are two very rare and highly important early Bijapuri royal portraits dating from the late 16th century. The portraits, which depict the Bijapuri Sultans 'Ali 'Adil Shah (r.1557-1579) and Ibrahim 'Adil Shah (r.1579-1627) respectively, are examples of only a very small number of Deccan royal portraits dating from this period.

Both works were probably presented by the Bijapur royal family to the Mughal Emperor as part of a royal tribute at the beginning of the seventeenth century. This is indicated by the identification inscriptions featured on both works which are likely to have been written by the Mughal Emperor Jahangir himself. The paintings will be offered as two separate lots, each of which are each expected to achieve £150,000 - £200,000.

The auction will also bring to the market an important and rare Bijapuri equestrian portrait from the seventeenth century. Although the identity of the majestic mounted figure depicted here is uncertain, it is most likely to be a portrait of a senior Mughal courtier named Ja'far Khan who lived in Deccan at the time.

A Mughal nobleman riding through a landscape holding a hawk. India, Deccan, Bijapur, circa 1660-1680. Estimate £50,000-£70,000.

Gouache and gold on paper, depicting a mounted nobleman holding a hawk on his right hand, a retinue with elephant following, within a landscape, inscription to the reverse; 18.4 by 27.4cm.

Note: This is an important and rare equestrian portrait painted at Bijapur during the third quarter of the seventeenth century.

It is close in style and palette to the well-known dynastic durbar scene The House of Bijapur by Kamal Muhammad and Chand Muhammad in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1982.213; see Zebrowski 1983, pl.XVII, Welch 1985, no.208, Haidar and Sardar 2011, frontispiece and cover detail). Indeed, the execution of the horse, the rocks and the trees in that work is very close to those in the present example. It also relates stylistically to other Bijapur works, including A Princely Deer Hunt, datable to circa 1660, in which the horses and palette again relate to the present work (see Welch 1985, no.207; Zebrowski 1983, no.115), and Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah before a distant vista, a mid-seventeenth century work by Muhammad Khan, son of Miyan Chand, where the background hills and trees are close to the present example (see Zebrowski 1983, no.94).

The identity of the mounted figure here is uncertain. By the time this work was painted, the Mughaloverlordship of the Deccan was well-established and Mughal princes and officers were frequent visitors andresidents. Furthermore, Mughal artistic influence was assimilated into Deccani art. The facial type of the main figure, as well as the composition in general, is clearly influenced by the Mughal school (for a closely related Mughal equestrian hawking scene of the same period in the India Office Library Collections, British Library, see Falk and Archer 1981, p.410, no103; Losty and Leach, no.11). The figure wears a beard of a distinctly Mughal fashion associated with the reign of Shah Jahan and the early years of Aurangzeb's reign.

An inscription on the reverse gives the name Ja'far Khan. There were several noblemen and courtiers of the Shah Jahan and Awrangzeb periods with this name, but the two most likely are the Ja'far Khan who was Mir Bakhshi from 1647 onwards, and the Ja'far Khan who was Umdat al-Mulk, minister and governor towards the end of Shah Jahan's reign and Grand Vizier under Awrangzeb. A portrait of the former, by Chitarman of circa 1645 (British Museum, 1920,0917,0.13.36, see Beach and Koch 1997, fig.114, p.192) shows him to have had a similar physiognomy to the present figure, and other portraits of him, including numerous appearances in groups scenes in the Padshahnama and related works, confirm the similarity, albeit occasionally with a straighter nose (see Beach and Koch 1997, pages as indexed) . The latter is shown in a Deccani portrait of circa 1670 in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (69.8, see Leach 1995, vol.II, pp.951-2, no.9.682, p.955, col.pl.138). The Deccani origin of this seated portrait perhaps provides a link to the present work, also

of Deccani origin; however, even allowing for the much greater age of the sitter, the facial features are less akin, leaving the former courtier as the more likely match.

Since the inscription on the reverse has probably been written somewhat later than the execution of the painting itself, it is also possible that the figure here is meant to depict someone else, perhaps a royal figure, and it is worth noting that a closely related drawing of Shah Jahan carrying a hawk as he processes across a landscape with his army is in the Freer Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (F1907.196, see http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/zoomObject.cfm?ObjectId=3416, where it is described as Mughal, although it is quite possibly Deccani in origin). The prince with the closest facial characteristics is Prince Dara Shikoh, Shah Jahan’s eldest son and heir apparent, who is often shown with a very slightly more convex line to his nose, and with the same type of Shah Jahan-fashion beard as seen here (see, for instance: Dara Shikoh (one of four portraits on an album page), Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., S1986.421, see Beach 2012, no.22I; Shah Jahan Receiving Dara Shikoh, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.83.105.21, see Pal 1993, pp.282-3, (which clearly shows the slight difference between Dara Shikoh's visage and Shah Jahan's); Dara Shikoh with a Tray of Jewels, Victoria and Albert Museum, IM 19-1925, see Stronge 2002, pl.115; Dara Shikoh with Mian Mir and Mulla Shah, Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., S1986.432, see Beach 2012, no.36; Dara Shikoh and Sulaiman Shikoh, sale in these rooms, 16 June 2009, lot 2; Portrait of Dara Shikoh, Christie’s, London, 10 October 2006, lot 166). A further very close resemblance can be seen in a small portrait in the Dyson Perrins album, included in this sale as lot 102. Dara Shikoh’s brother, Prince Shah Shuja, also has the very slightly convex nose profile (see a portrait in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Leach 1995, no.3,82, Wright 2008, no.81), and he is also a possible candidate for the subject here. However, if the painting does show a royal prince, which the symbolism of the mounted, hawking figure might imply, it is slightly odd that he is depicted without a nimbus, which portraits of royal princes of the Mughal dynasty would normally have. Thus the probability remains that it does indeed depict one of the senior Mughal courtiers named Ja'far Khan.

RARE CRAFTSMANSHIP & CERAMICS

A sale highlight that is particularly noteworthy is the auction of Dr Conrad Schick’s model of the Dome of the Rock, an outstanding museum piece of great historical interest and educational importance. Ingenious, inspired and pedagogical, it embodies the spirit of the Age of the Great Exhibitions. The architect and archaeologist was commissioned by the Ottoman Sultan ‘Abd al-Aziz to create the monumental wooden model of The Dome of the Rock, one of the most sacred sites in Islam, for the 1873 World Fair in Vienna. Schick’s highly accurate and ornate model, which is almost two metres square, represents an invaluable record of how the building stood in former times. The only other models produced by Schick known to have survived, those of the Temple Mount and the Jewish Temple, are held by private institutions and are unlikely ever to come to market.

A Wooden Model of the Dome of the Rock, by Dr Conrad Schick, Jerusalem, 1872-3 - Sotheby's.

constructed of wood and plaster, on a rectangular base with handles and sliding mechanism to reveal the interior representing the innermost part of the Haram al-Sharif, with the Dome of the Rock and surrounding buildings including the Dome of the Chain, Dome of the Prophet, Dome of the Mi’raj, Dome of the Hebronite and Minbar of Burhan al-Din, polychrome decoration throughout, featuring a number of small figurines each individually modelled. base: 190 by 195cm. Estimation: 250,000 - 300,000 GBP

The Dome of the Rock

The Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem is one of the most sacred sites in Islam, ranking third in importance after the Two Holy Mosques of Mecca and Medina. The symbolic significance of this building to Muslims around the world should not be underestimated. Its special status and historical pre-eminence resonates with the entire global Muslim community. Not only does it stand on the spot where Abraham (or Ibrahim, as he is referred to in the Qur’an) purportedly attempted the sacrifice of his son Isaac, but it also marks the site where The Prophet Muhammad ascended into Heaven. Some maintain that the Rock itself is the very seat upon which God the Father will sit in judgement on the final Day of Reckoning.

The elegant domed octagon, which has its origins in late Roman and Byzantine structures, is of great interest to scholars and historians of Islamic art. It represents both continuity with the ancient Classical world, and yet is an emphatic statement of a new world order. It is also one of the earliest buildings that can be directly attributed to a Muslim royal patron, ‘Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad Caliph who inaugurated the monument in 691 CE and whose name is emblazoned in gold Kufic letters around the interior. This inscription is the earliest surviving use of Qur’anic text recorded in a monumental context. When the building was first erected in the late seventh century it was intended asa bold proclamation of the triumph of Islam, raised at the symbolic centre of the ancient capital of Judaism and Christianity. Even today it has lost none of its spiritual and political potency. The building still functions as a place of daily worship and yet it has always been much more than that, standing prominently above the city skyline, proclaiming the pride and ambition of Dar al-Islam (the “House of Islam”).

Dr Conrad Schick (1822 –1901)

Architect, town-planner and archaeologist, Dr Conrad Schick is remembered today principally for his remarkable architectural models. The present model is at once monumental, yet intricate in its design and craftsmanship, as revealed by glimpses into its richly painted and carved interiors. Whereas this attention to detail can be credited to the rigorous precision of his training as an architect-engineer in the Swiss-German tradition, Schick’s ability to capture the essence of this landmark can be ascribed to his deep knowledge of the city of Jerusalem and its archaeological landscape. Born in Baden-Württemberg in 1822 and schooled in Kornthal and Basel, Schick’s association with Palestine began in October 1846 when, at the age of twenty-four, he travelled to the Holy Land to work as a missionary on behalf of the Reformed St. Chrischona Pilgrim Mission of Bettingen. He settled in Jerusalem and lived with his family on the Street of the Prophets, in a house which he himself constructed, and which still stands today, named Beit Tabor, or Tabor House. Schick was to spend the rest of his life in Jerusalem, acquiring an unrivalled knowledge of the city. He died on 24 December 1901 at the age of eighty and is buried in the Protestant cemetery on Mount Zion. Schick worked on a number of buildings and architectural schemes in Jerusalem as well as being at the forefront of many of the city’s archaeological projects. In Jerusalem he is perhaps best known as the architect of the new Mea Shearim neighbourhood, one of the first to be built outside of the Old City walls. He also participated in a research project on the subterranean structures within the Haram al-Sharif, or “Noble Sanctuary” on the Temple Mount, which provided him with exact information for his architectural models.

In 1872, at the behest of the Ottoman authorities, Conrad Schick was given the rare opportunity to survey the entire site of the Haram al-Sharif, which had hitherto been off-limits to European archaeologists. Schick went on to construct a large wooden model of the Haram as well as the present model of the Dome of the Rock, both of which were exhibited at the World Fair in Vienna in 1873. The present model is accompanied by two copies of the original pamphlet which was published at the time of the Vienna exhibition, entitled Erklärung der Modelle des Haram Es Scherif und der Sachra Moschee in Jerusalem (“An explanation of the models of the Haram al-Sharif and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem”, Vienna 1873, Diuck von M. Bettelheim & J. Pick. Verlag von J. H. Brühl). Conrad Schick’scommitment to education is demonstrated in a letter addressed to a colleague, Charles Wilson, dated 7 June 1872, in which he emphasises the fact that he wanted his models to be used didactically, as learning tools for “students of history and topography” (Gibson, S., and Jacobson, M., "The Oldest Datable Chambers on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem", The American Schools of Oriental Research, 8 November 2008). Schick went on to create further models of other religious buildings in Jerusalem, notably, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the historic Jewish Temple.

The latter was listed in Baedecker’s 1876 guide to Jerusalem, and was praised by Barnaby Meistermann, a Franciscan priest, who in 1923 wrote that the city “should not be left without seeing the exact model of the Temple made from painted wood by Mr Schick” (E.W.G. Masterman, “Obituary: The Important Work of Dr. Conrad Schick”, The Biblical World, Vol.20, No.2, 1902, pp.146-148).

The Conrad Schick Model

The monumental wooden model, commissioned by the Ottoman sultan ‘Abd al-Aziz and displayed at the 1873 World Fair in Vienna, is a unique historical document recording the Dome and surrounding buildings as Conrad Schick found them in 1872. Schick’s eye for detail and unwavering pursuit of archaeological veracity has bequeathed to us a three dimensional record of astonishing fidelity. Many elements in the building, including the lead grey covering of the domeand the polychrome interior have been altered in more recent times. The model thus represents an invaluable record of the building as it stood in former times, before modern renovations and “improvements”. Ingenious, inspired, and pedagogical, The Conrad Schick Model embodies the spirit of the Age of the Great Exhibitions. The only other models produced by Schick and known to have survived, those of the Temple Mount and the Jewish Temple, are held byprivate institutions in Jerusalem and are unlikely ever to come to the market. The sale of The Conrad Schick Model of the Dome of the Rock is thus a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to acquire an outstanding museum piece of great historical interest and educational importance.

For more information on Conrad Schick, see: August Strobel, Conrad Schick ein leben für Jerusalem, Zeugnisse über einen erkannten Auftrag, Germany, 1988.

E.W.G. Masterman, “Obituary: The Important Work of Dr. Conrad Schick”, The Biblical World, Vol.20, No.2, 1902, pp.146-148

For a full list of Conrad Schick’s early works, see: Reinhold Röhricht, Bibliotheca Geographica Palaestinae, Berlin, 1890.

A silk and metal-thread brocade cover (masnad), Persia, 18th century, Estimate £100,000-£150,000.

This teal blue silk brocade, so large that it was probably woven for a ceremonial purpose, may once have adorned a throne dais. At the very least it was a large ‘masnad’, intended for a nobleman to sit upon when on the floor. Once owned by the Counts Potocki who lived in Ukraine during the seventeenth century, it is decorated with golden thread and depicts a trellis enclosing floral sprays and shrubs, with a highly unusual border of stylised leaves.

A silk and metal-thread brocade cover (masnad), Persia, 18th century - Sotheby's

the teal blue silk ground with an overall arabesque-formed trellis enclosing floral sprays in golden hued metal thread and ivory silk within a wide border of stylised leaf forms also in metal-tread, small diamond patterned upper and lower guard stripes, original selvages intact, fabric backed.

PROVENANCE: Count A. Potocki, Buczacz, Ukraine, 18th/19th century (initials A.P. and the Piawa coat of arms on an old label to reverse)

Gift from Mr Job F. Angell, Glen Ridge, New Jersey, to:

The Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey, 1943, from whence deaccessioned

The town of Buchach (Buczacz in Polish) is a city located on the Strypa River in Ternopil Oblast of western Ukraine(formerly part of Poland and then the USSR). Having previously been a village within the Buczaczki estates, known for its castle and fortress, it fell into the hands of the Counts Potocki at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Count Stefan Potocki, a voivode from Bratslaw, broadened and strengthened the palace and fortress, which came undersiege by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV in 1672, 1675 and 1676 (when it was finally captured, and almost destroyed, by the Turks).

NOTE : The unusually large size of this brocade panel may indicate that it was woven for a ceremonial purpose such as the adornment of a throne dais. At the very least it is a large masnad, intended for a nobleman to sit upon when on the floor (as illustrated in miniature painting; see, for example, folio 18IV of the Shahnameh made for Shah Tahmasp in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, published in The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2011, p.136). A related large scale Persian brocade cover with an overall floral lattice, with a more typical striped border design, is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, cat. no. 44.53.8 (see online 'Collections'). The overall design of a trellis enclosing floral sprays or shrubs recalls Mughal Indian carpets and textiles of the seventeenth century. While referencing previous patterns, the arabesque-formed trellis here is much more intricate and is executed in a very different colour palette than those found in earlier works.

This panel includes a highly unusual border of stylised leaves or palmettes that does not appear in Safavid or Mughal textiles known to date. While the field design is derived from a Mughal prototype, the upper and lower guard borders of a small diamond or checked pattern in this brocade is a motif distinctly Persian and found in both textiles and rugs.

For eighteenth-century Persian brocades incorporating Safavid and Mughal elements, see Patricia L. Baker, Islamic Textiles, London, 1995, pp.127 and 129; and Carol Bier, Woven from the Soul, Spun from the Heart, Washington, D.C., 1987, pp.142-3. pl.3.

A highly important ivory-inlaid Indo-Portuguese cabinet of Royal provenance, Goa, India, late 17th century Estimate: £200,000-£300,000

Standing majestically on four sculptural bird-form feet with caryatid figures on each corner supporting the structure, this cabinet represents an exceptional example of Indo-Portuguese craftsmanship. The rare and extraordinary work has passed through the hands of three very distinguished royal houses of Europe, Braganza, Saxe-Coburg, and Hohenzollern. Dating to the 17th century, it was most likely a special commission for the Portuguese Royal family. Composed of Indian coromandel wood, it is inlaid with ivory tinted in a kaleidoscope of colours and is decorated with serpent heads, naginas and solid ivory caryatids.

A Highly important ivory-inlaid Indo-Portuguese cabinet of Royal Provenance, Goa, India, late 17th century - Sotheby's

comprising three sections, the upper part fitted with eight short drawers and a combined deep drawer in the centre, decorated on the top and sides with etched and stained ivory inlay to form scrolling foliate tendrils with figures of naginas to each corner and lion-heads, the frontal drawers with a design of scrolling tendrils issuing serpent heads and with frontal human faces on each corner, the middle, rectangular section with two long drawers with similar designs to front and sides, the stand with two hinged doors and large compartments between a sculpted nagina, raised on legs sculpted as winged animals supporting four corner caryatid figures, with a similar design of serpent-head tendrils and naginas with entwined tails to each corner, back plain, brass plaque to reverse of upper section inscribed 'F.R.', old collection label under base, piece includes three keys. 143.5 by 92 by 90cm.

PROVENANCE: Queen Maria da Gloria of Portugal and the Algarves (1819-1853) and Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1816-85), King Consort of Portugal under the name of Ferdinand II (1837-53) and Regent of the Kingdom of Portugal (1853-55)

By descent to their youngest daughter Antonia, who married Leopold Fürst von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1835-1905), Schloss Sigmaringen

Sold at Sotheby's, Aus Deutschen Schlössern "Ancestral Attics", Schloss Monrepos, 9-14 October 2000, lot 100

NOTE: This rare and extraordinary cabinet has passed through the hands of three very distinguished royal houses of Europe, Braganza, Saxe-Coburg, and Hohenzollern. Dating to the 17th century, it was most likely a special commission for the Portuguese Royal family and later found its way to Schloss Sigmaringen, the seat of the family of the Fürsten von Hohenzollern.

Standing majestically on four sculptural bird-form feet with caryatid figures on each corner supporting the structure, this cabinet represents an exceptional example of Indo-Portuguese craftsmanship. Also known as a contador, this type of cabinet blends the traditionally Western form of a standing cabinet with decoration and elements of design that contain both Mughal and Hindu influences. Composed of Indian coromandel wood, it is inlaid with ivory tinted in multiple colours, notably green, which has been particularly associated with Mughal-inspired Gujarati designs and colouring. This area, along the Western coastal region of India was a well-known centre of production for ivory-inlaid articles aimed at Western markets.

The ivory inlay decoration on this cabinet is exceptionally fine, with a detailed and fluid composition. The frontal drawers each feature a vegetal scrolling design with serpent-head terminals. The faces on each corner are evocative of the allegorical figures representing the winds on European maps. This interesting mix of themes and motifs continues on to the large rectangular panels supporting the cabinet which are highlighted by naginas at each corner. These mermaid-like creatures, with their entwining tails, are indigenous snake divinities that are considered to bring good fortune and protection. Similar, sculptural naginas adorn a pulpit in the Igreja de Varca in Salsete, Goa (M.M de Cagigal e Silva, A Arte Indo-Portugesa, edicoes excelsior, 1966, p.203, fig.115).The design to the top and sides of the cabinet further incorporates images of frontally-facing lions, symbols of royalty and power.

The faces of the corner caryatid figures and of the central nagina are carved from solid ivory, an extremely precious material. It has been suggested that these were carved by Chinese craftsmen working in Goa or could have come as a special commission from the Chinese ivory workshops in Macau. These figures stand above four winged birds which resemble those on an elegant contador dated to the seventeenth century now in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon, inv. no. 1416. It is interesting to draw a link between these and bird-form foot stands that adorn other contadors such as those on one in the Victoria and Albert Museum (inv. no. 781-1865), which have been compared to representations of jatayu, a demi-god in the form of a vulture who played a central role in the Hindu epic, the Ramayana (Jaffer, A., Luxury Goods from India, London, 2002, pp.56-57, no.21).

Notable for its sumptuous appearance and the exotic materials which adorn it, this important cabinet is also notable for its royal provenance. Its provenance is further attested by a brass inventory plaque with the initials F.R. which refer to Ferdinand Saxe-Coburg and Gotha who married Maria II da Gloria, Queen of Portugal and the Algarves in Lisbon on the 9th of April 1836. Their youngest daughter, Antonia, married intothe Hohenzollern family, becoming Antonia Fürstin von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, and brought with her to Sigmaringen Castle many Portuguese furnishings and decorative objects.

The present cabinet can be compared to a small collection of cabinets found in the Nationalmuseum of Stockholm which had originally been commissioned from India in 1580 by Baron Clas Felming and his wife Ebba Stembock (M.M.E. Marcos, Marfiles de las provincias ultramarinas orientales de Espana y Portugal, Monterrey, 1997, pp.328-329). The demand for such works from prestigious royal clients is further attested by another example of a seventeenth-century Indian cabinet decorated with crowned bicephalous-eagles associated with the Habsburgs.

A UNIQUE IZNIK POTTERY WATER FLASK (MATARA), TURKEY, CIRCA 1580-90, ESTIMATE £70,000-£100,000

The sale will also include an extraordinarily rare sixteenth century Iznik water flask. The flask, fashioned to look like a traditional leather vessel used across the Ottoman Empire at the time, is wholly unique. Humble utilitarian objects were imitated in a number of luxurious materials across this period. It is likely that such traditional forms and objects were prized, celebrated for their links to history and the past.

A unique Iznik pottery water flask (matara), Turkey, circa 1580-90 - Sotheby's

of characteristic form with two short tapering spouts and a curved handle, a raised ridge bisecting the body vertically, decorated in underglaze red, cobalt blue and green with an overall marbling pattern; 17.8cm. Estimation: 70,000 - 100,000 GBP

PROVENANCE: Private Collection, Malaysia, 1980s

Sold in these rooms, 11th October 1989, lot 133.

EXHIBITED: Leighton House, London, 1982

LITTERATURE: Atasoy and Raby 1989, p.277, no.634

Carswell 1998, p.84, no.64

NOTE: This extraordinary rarity owes its form to a leather vessel made from the hind quarters of a quadruped, the two spouts imitating the projecting legs. Though unique to this object in pottery, the form is familiar from its appearance in other elevated media. In what is perhaps a typically Ottoman approach, the form of a humble utilitarian object is imitated in a number of luxurious materials in this period. Notable examples of this are two flasks of this form in the Topkapi Saray Museum, both contemporary to the Iznik matara and both carved from rock crystal and mounted in gold (illustrated in Atasoy and Raby 1989, p.277, no.633, and Atil 1987, p.129, no.60). The marbling pattern of this Iznik example may itself be intended to suggest carved stone, the raised ridge playing the role of a mount. Where marbling is used in an architectural context, such as on the tilework of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul, it clearly has this suggestive intent.

The ‘hanap’ or tankard form, see lot 243, is another example of the use of a day-to-day form reworked as a luxury object. Rather than for their lowly status, it may be speculated that these forms are prized as traditional and therefore are celebrated as a self-conscious historical allusion just as a reverence for tents, albeit rather grand ones, continued long after the building of luxurious palaces. Whatever the significance of these borrowings, it is clear that the use of forms and designs from other media was frequent in the later reign of Murad III (1574-95). The appearance of forms such as the conical tankard and the so-called ‘animal style’, both derived from Balkan silverware, is another notable occurrence of this practice in this period of Iznik production (see Atasoy and Raby 1989, p.276, nos.615-621, and p.256).

BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS

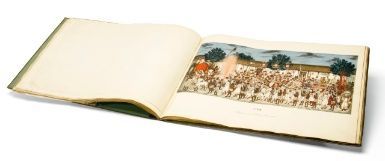

A large and important album of watercolours of costumes, craftsmen, trades, processions and dignitaries, India, Vellore, Company School, circa 1832-35 Estimate £200,000-300,000

This large album of very fine watercolours depicting scenes of nineteenth century Indian life, commissioned by an East India Company official living in Vellore during the 1830s, provides a fascinating insight into the Indian culture of the period.

A large and important album of watercolours of costumes, craftsmen, trades, processions and dignitaries, India, Vellore, Company School, circa 1832-35 - Sotheby's

Watercolour with gold on 35 large sheets of paper watermarked ‘J Whatman Turkey Mill’ and 'Ruse & Turner', index at beginning written in a fine 19th-century English hand in black ink, green paper doublures, original gilt- and blind-stamped black morocco covers; 36.9 by 53cm. Estimation: 200,000 - 300,000 GBP

NOTE: This large Company School album is remarkable for the size, quality and range of subjects of the watercolours, and also for the fact that the painting on sheet XXXIV is a self-portrait of the artist engaged in painting, while an assistant holds this very album under his arm. Furthermore, on sheet XXXIII is a depiction of a colonial-style bungalow in a large garden entitled 'May Place, Vellore', which is surely a painting of the residence of the East India Company official who commissioned the album.

The quality of the watercolours is very fine and superior to the majority of related productions of Company patronage, showing a strong attention to detail as well as a lively appreciation of movement and action in the processional scenes.

The album consists of thirty-five large sheets of Whatman and Ruse & Turner paper (of varying dates between 1821 and 1828) bound in its fine original leather covers. Most sheets bear three groups of two figures representing a variety of trades, crafts and individual characters, each with a male and female figure. There are also several group scenes of dancers, four processional scenes (‘Procession of Vistnu’ (sic); ‘Procession of Sivah’; ‘Procession of a Hindoo Marriage’ and ‘Procession of a Mussulman Marriage’), a sheet of four agricultural scenes, the aforementioned view of May Place, Vellore, and the self-portrait of the artist. The portraits of dignitaries include the former King of Kandy, his son, and the Prime Minister of Ava. There is onesheet with portraits of six soldiers of the Madras regiments of Horse Artillery, Light Cavalry, Rifle Corps, Pioneer Corp, Infantry and Golundauz (a gunner of artillery).

The focus of the album, as well as its pictorial style, is the southern and eastern regions of India. Vellore itself, mentioned on sheet XXXIII, is on the Palar River in modern-day Tamil Nadu, between Madras and Bangalore. Other aspects of the album also relate to this general area of India: on sheet XXVII is a depiction of a 'Seringapatam Mussulman', the uniforms of the soldiers depicted on sheet XXXI belong to Madras regiments (a watercolour of circa 1835 showing two identical uniforms and labelled 'Madras Light Cavalry' and 'Madras Horse Artillery' is in the National Army Museum, London, Inv.1965-04-18-2) and the title given by the artist to the self-portrait on sheet XXXIV includes the term 'Moochee' which usually means a shoemaker or leather-worker, but in South India can also mean an artist or gilder (see Hobson Jobson, p.579).

A very similar album, of almost identical dimensions and with a similar number of watercolours, is in the India Office Collections, British Library, London (Add.Or.39-70). It is described by Mildred Archer as "Probably by a Tanjore artist, working at Vellore, c.1828". Several of the figural scenes are identical to those in the present album, including one of a group of dancers, which is identical in composition to the 'Mussulman Dancing Girls' on sheet XXVIII of the present album (Add.Or.62, see Archer 1972, pl.8). In addition, the British Library album contains a painting of the bungalow of the Fort Adjutant at Vellore, recalling the watercolour on sheet XXXIII of the present album labelled 'May Place, Vellore'. It is probable that the same artist produced both albums.

The present album's inclusion on sheet XXXV of a depiction of "The Son of the late Ex-King of Kandy and his two Uncles" is particularly interesting. After his deposition in 1815 by the British, the king and his family were transferred to Madras and from there to Vellore, where they were kept under glorified house arrest in a building inside Vellore Fort which is still known today as the Kandi Mahal.

The fact that the family was kept in Vellore Fort is clearly the reason for the inclusion of this painting of his son on sheet XXXV, since it would have had direct local relevance, and this, in addition to the inclusion of a specific Vellore building on sheet XXXIII, helps confirm the location of production of the album as Vellore itself (as suggested by Mildred Archer in relation to the sister album in the British Library). It also allows us to narrow the date of production, since the title of the image on sheet XXXV clearly indicates that the ex-King had already died, meaning the album must have been produced after January 30th 1832.

The full list of watercolours is as follows (copied verbatim from the index at the beginning of the album):

No. I. Procession of VISTNU

No. II. Procession of SIVAH

No. III. Gentoo Bramin

Streevystoom Bramin

Maharatah Bramin

No. IV. Rachavar

Rajapool

Goozraul

No. V. Banyan

Barywar

Singavunt

No. VI. Buljavar

Bungadee Maker

MoodaliarNo. VII. Ryot

Kummavar

Bricklayer

No. VIII. Silk Weaver

Cotton Weaver

Taylor

No. IX. Iron Smith

Carpenter

Gold Smith

No. X. Cauyet

Mahratah Taylor

Moochee

No. XI. Oil Monger

Cowkeeper

Cubaudy

No. XII. Palankeen Bearer

Fisherman

Matt Maker

No. XIII. Taddy Drawer

Coorpavar or Cumbly Maker

Cortee or Malabar Basket Maker

No. XIV. Pott Maker

Barber

Washerman

No. XV. Tank Digger

Korchavar or Basket Maker

Lumbaudy or Brinjarie

No. XVI. Poligar Peon

Shicaree or Huntsman

Nuckul Jogy

No. XVII. Moochy or Shoe Maker

Village Toty

Chuckler

No. XVIII. Byrauggee

Gosayee

Fakeer

No. XIX. Sautany

Pundaurum

Dausary

No. XX. Poojawry

Maryamah Poojary

Cur Cur Bundah

No. XXI. Agricultural Occupations

No. XXII. Sawmy Bull

Haukery

Puckally and Bullock

No. XXIII. Hindoo Dancing Girls No. XXIV. Procession of a Hindoo Marriage

No. XXV. Ex King of Kandy

No. XXVi. Kee wonghee or Prime Minister of Ava

Burmese Officer

Burmese Woman

No. XXVII. Navayet

Seringapatam Mussulman

Lubbavar

No. XXVIII. Mussulman Dancing Girls

No. XXIX. Procession of a Mussulman Marriage

No. XXX. Duffadar

Hircarrah

Mahal Nazers

Native Doctor

Dauyee

No. XXXI. Trooper of Horse Artillery

Trooper to Light Cavarly

Sepoy of Rifle Corps

Sepoy of Pioneer

Sepoy of Infantry

Sepoy of Golundauz

No. XXXII. Butler Teeroovaugadum Moodily

Dressing Servant Dassy

Taylor Madara

Waiting Servant Modeen

Maty Orlando

Cook Chinatomby

No. XXXIII. May Place Vellore

No. XXXIV. Yellapah Picture Moochee

No. XXXV. The Son of the late Ex-King of Kandy & his two Uncles

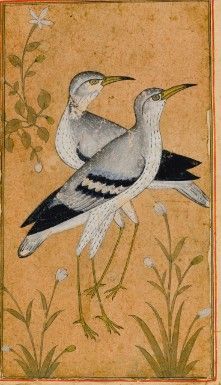

A rare concertina-form album of miniatures and calligraphy (Muraqqa’) Persia, 16th-19th century, Estimate £50,000-70,000

The auction will also include an extremely rare album of drawings and calligraphy. While many such albums, traditionally collected and coveted by courtiers and other wealthy patrons, have been broken upon over the centuries and dispersed into countless collections, this muraqqa’ is exceptional for remaining intact. Assembled in a charming personal manner, probably in the nineteenth century, the 28 page album opens like a book: similar animals, dervishes and other figures confront each other, interspersed with various calligraphic panels. Comprising illustrations and illuminations dating from between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the album is estimated at £50,000 - £70,000.

A Rare Concertina-form Album of Miniatures and Calligraphy (Muraqqa’), Persia, 16th-19th century - Sotheby's

Of concertina form, 28 album pages in total joined together, within a late 19th-century leather binding with lacquer borders filled with scrolling gilt foliage and red doublures, start and end of album with 2 Qajar lacquered miniatures of Fath 'Ali Shah Qajar and a stag, the rest of the leaves comprising 20 miniatures depicting figures, birds and animals, 6 panels of calligraphy and 2 photographs cut from circa 1900 book-plates, the miniatures and calligraphy laid down with outer 16th-19th illuminated borders; 32.5 by 20.5cm. 612cm. extended. Estimation: 50,000 - 70,000 GBP

NOTE: The present muraqqa' represents an extremely rare intact album of drawings and calligraphy, many such albums having been broken up into their constituent parts over the centuries and dispersed into countless collections.

Drawings began to be kept in albums from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, as demonstrated by the albums housed in the Topkapi Saray Museum. By the end of the sixteenth century drawings were in high demand, collected by rulers such as Shah 'Abbas as well as courtiers and other wealthy patrons. The present album, judging by the varied content, borders and binding, appears to have been put together in the late nineteenth century, and has been assembled in a charming, personal manner; when opened like a book, similar animals, dervishes and other figures confront each other, interspersed with various calligraphic panels. The contents of the muraqqa’ is as follows:

fl.1a. A lacquered portrait of Fath ‘Ali Shah on horseback with an attendant, Persia, Qajar, 19th century

fl.1b. A drawing of dervish holding a cup and bottle, Persia, Safavid, second half 17th century

fl.2a. A drawing of a dervish holding a pomegranate, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.2b. A coloured drawing of a couple by a stream, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.3a. A coloured drawing of youth at study, Persia or Deccan, mid-17th century

fl.3b. A coloured drawing of a European drinking from a bottle, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.4a. A coloured drawing of a European holding a vase of flowers, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.4b/5a. Two illuminated nasta’liq quatrains, Persia, Qajar, 19th century

fl.5b. A partially coloured drawing of fantastical intertwined animals, Persia, Safavid, 16th century fl.6a. A drawing of a dragon emerging from its lair, signed by Murtaza Quli Shamlu, Persia, Safavid, mid-17th century

fl.6b. A drawing of a dervish within a rocky landscape, style of Reza-i 'Abbasi, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.7a. A partially coloured drawing of a dervish under a tree with a huqqa, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.7b. A drawing of a simurgh chick, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.8a. A coloured drawing of a pair of lapwings, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.8b/9a. Two printed illustrations from Wa’iz Kashifi’s al-mawahib al-alliyya, circa 1900

fl.9b. A drawing of a dervish leaning on a stick, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.10a. A small drawing of a kneeling dervish, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.10b. A drawing of a bear chained to a post, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.11a. A partially coloured drawing of a strutting camel, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.11b. An illuminated quatrain in nasta’liq script, signed by Mir ‘Ali, Persia, Safavid, 16th century

fl.12a. A panel of illuminated calligraphy in shikasteh ta’liq script, attributable to Ikhtiyar al-Munshi, Persia, Safavid, 16th century

fl.12b. A drawing of a maiden wrapped in a shawl, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.13a. A partially coloured drawing of a lady holding a bottle, signed by Aqa Reza, Persia, Safavid, late 16th century

fl.13b. A drawing of a mounted hunter, attributable to Reza-i ‘Abbasi, Persia, Safavid, late 16th century

fl.14a. Two drawings: a kneeling youth with cup and bottle and a heron catching a snake, Persia, Safavid, 17th century

fl.14b. A lacquered painting of a stag, Persia, Qajar, 19thcentury (with composite sections)

A number of miniatures in the present album are of considerable interest. The fluid and lively dragon crawling into life on fl.6a (see inside front cover) is signed by Murtaza Quli Shamlu, who is recorded by Karimzadeh as a commander at the court of Shah Suleyman (1077-1105 AH/1666-94 AD) with the post of ‘sword holder’ and governor of Qom (see Mohammad Ali Karimzadeh Tabrizi, The Lives & Art of Old Painters of Iran, vol. 3, London 1991, pp.1144-5). Four works by him are recorded, but only one is dated (1064 AH/1653-4 AD). A further drawing by Murtaza Quli Shamlu, a lion chained to a post, was sold in these rooms 2 May 1977, lot 95.

Folio 13b depicts a finely executed and detailed horse and rider, similar to a drawing signed by Reza-i 'Abbasi that represents part of an album page sold in these rooms, 8 July 1980, lot 212 and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (published in S. Canby, The Rebellious Reformer, London, 1996, p.52, Cat.16). The treatment of the horse's head, knotted tail, as well as the rocky landscape are so closely comparable in both drawings that we can suggest the possibility of master artist Reza-i 'Abbasi as responsible for both.

A further highlight of the muraqqa' is the portrait of the lady holding a bottle, signed by Aqa Reza, on folio 13a. Aqa Reza was the name of the young Reza 'Abbasi before he entered the service of Shah 'Abbas in the late sixteenth century. This particular drawing can be compared to a portrait of a 'Woman With a Veil', attributed to Reza-i 'Abbasi in the Art and History Trust Collection, (published in Soudavar 1992, pp.270-1, no.109). The figure's robes, as well as the light gold plants and cloud bands in the surrounding space, are very similar, as too is the execution of the face, particularly the treatment of the eyes, lips and chin.

Three miniatures of dervishes within the album (those on folios 6b, 9b and 10a) also share similarities with the work of Reza-i 'Abbasi. The kneeling dervish with his prayer beads (fl.6b) shares a striking likeness with another dervish by Reza's hand dated 1035 AH/1626 AD, particularly the nose, and it is known that dervishes were among Reza's favourite subjects (see ibid, p.269, no.108).

Whilst the simurgh chick (fl.7b), mischievous bear (fl.10b) and strutting camel (fl.11a) exhibit charm andhumour, (the latter is a topos the like of which can be found in numerous places, including the Harvard University Art Museums, see S.C. Welch and K. Masteller, From Mind, Heart, and Hand, Cambridge, MA, 2004, pp.41-43, no.2), perhaps the best qualilty work in the album can be found on folio 5b, in which we see an extraordinary intertwined fantasy of birds, fish, dragons and foliage, with the stems terminating in dragon and bird heads. Complex compositions such as these, whilst decorative art works in themselves, were often working sketches for drawings and paintings, or design sketches for the decoration of objects in other media, such as textiles, ceramics, chests or bookbindings. The present example can be compared to a panel of arabesques with a dragon parrot in the Harvard University Art Museums (published in ibid, pp.38-40, no.1), as well as a decorative drawing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (M.L. Swietochowski and S. Babaie, Persian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1989, pp.12-13, no.1).

METALWORK

A rare and important gold and silver-inlaid dagger Ghaznavid or seljuk, Eastern Persia, 11th/12th century Estimate £500,000-£700,000

Dating from the 11th or 12th century, this gold and silver dagger is an extremely early and rare example of a courtly piece of weaponry. It is a remarkable survival: very few extant examples of such daggers are known to exist, and, of the small number of surviving pieces, an even smaller number are decorated with such astonishingly intricate and beautiful inlaid designs as seen here. The dagger, which still retains its original wood hilt, has an ornate curved steel blade finely inlaid with gold and silver friezes of running animals and bands of cursive calligraphy, providing a rare insight into the manner in which the elite of this period chose to ornament their lives.

A rare and important gold and silver-inlaid dagger, Ghaznavid or Seljuk, Eastern Persia, 11th/12th century - Sotheby's

the gently curved stiletto blade cross-form in section with a flattened back edge in the section below the hilt, the vertical edges retaining inlaid decoration in gold and silver composed of friezes of running animals and bands of cursive calligraphy on a ground of foliate scrolls additionally with elongated rope-twist terminals, a top section of the back edge engraved with a repeating design of stylised palmettes within paired leaves all heightened with gilt, an integral collar engraved with bands of interlocking palmettes, possibly with traces of a resinous substance, and inlaid in silver with a symmetrical arabesque, housing a curved slender wood hilt, the domed pommel with traces of an inlaid gold scroll design; 43cm. Estimation: 500,000 - 700,000 GBP

inscriptions: al-umma (?) … [abi?]talib ‘Nation of’; [Abi?] Talib; wali al-anam [abi?] ‘Guardian of mankind [Abi] Talib’

The present dagger is an extremely early and rare example of a courtly piece of weaponry, with original wood hilt and steel stiletto-form blade finely inlaid with gold and silver stylised floral, zoomorphic and calligraphic decoration. There are very few extant examples of such daggers in museum and private collections, rendering the dagger to hand a remarkable survival.

Decoration

Of the small number of examples of weaponry of this period, including pieces in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Furusiyya Art Foudation, Vaduz and the Sabah Collection, Kuwait, an even smaller number are decorated with astonishingly intricate inlaid designs using gold and silver. There remains, in this dagger, sufficient inlay to understand the delicacy and beauty of its decoration. This lavish intent, taken with the other examples of this period, including those from the Khazar kingdom in the Caucasus (Paris 2007, p.29), promotes the notion that there was a tradition amongst the elite of the broader region, whether under the rule of the Khazars, Samanids, Ghurids, Ghaznavids or Seljuks, for weaponry decorated in a highly sophisticated manner. It is also a significant remnant of the material culture of this period and as such provides rare insight into the manner in which the elite of this period chose to ornament their lives.

Although there is one unpublished and closely related dagger in a Middle Eastern private collection, amongst the published examples of daggers with inlaid decoration in gold and silver there is distinct variation in the nature of the designs employed. Some seem to have parallels closer to contemporary textiles (such as Paris 2007, p.146, no.138).

The designs on the present dagger seem more closely comparable to friezes found on metalwork and carved stone of this period, though the elongated form may have necessitated this choice. The frieze of running animals has the same lively air as that carved into an ivory hilt of the eleventh-twelfth century and tentatively assigned to a workshop in Herat (Paris 2007, p.149, no.141). On another carved ivory hilt of this period is a design of interlocking palmettes handled in the same robust and almost playful manner displayed by those on our dagger. The combination of running animals and cursive calligraphy, the principal motifs on our dagger, appear together in a similar arrangement on a sword blade of this date also in the Furusiyya Art Foundation Collection (Paris 2007, p.38-9, no.9). These depictions of running animals were an established decorative scheme by the early years of Seljuk rule as can be demonstrated by a pencase in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, which has related friezes combined with calligraphy as well as a date of 607 AH/1210-11 AD (Washington 1985, pp.102-5, no.14). Made for the grand vizier of the last Khwarizmshahs, Ala al-Din Muhammad, its decoration is more formulaic than that of the dagger perhaps suggesting a slightly earlier date for the latter. The lively naturalism apparent in the designs on the dagger is more closely comparable to a freedom displayed in the repoussé and engraved metalwork of this period. Of the latter, a brass candlestick (sold in these rooms, 24 April 1997, lot 49) combines in its decoration bounding elongated animals with cursive script and rope-twist motifs, all of the elements displayed on the dagger. A similar sense of movement can be discerned in the animal frieze engraved on a bell metal tray in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Melikian-Chirvani 1982, pp.96-7, no.27). In terms of inlaid work, outside of the small group of daggers discussed, comparables can only be caught in glimpses such as on the hand-shaped terminal excavated at Nishapur (Allan 1982, p.104, no.186).

Form

Not only does the decoration vary amongst the small number of extant daggers of this period, but the forms of both hilt and blade are diverse. The narrow gently curving shape of our stiletto blade, ideal for piercing chainmail, is very similar to that of another dagger of this group (Paris 2007, p.150, no.143). This also has the broadened and decoratedsection of back edge just below the hilt. However the median ridge of our dagger is centred in a manner more closely comparable to another, though undecorated, example in the Furusiyya Art Foundation Collection (Paris 2007, p.147, no.139). The comparison continues to the use of a collar rather than quillons and to the wood hilt. The flattened section of the back edge shared by all three daggers becomes a characteristic feature of later Persian kards and the continuous curve from pommel to tip appears in later daggers as well.

The abovementioned dagger in a Middle Eastern private collection shares a similar hilt to the present example, and has a Kufic inscription dedicated to a ruler with the title of Taj al-dawla. This has been attributed to the late Ghaznavid ruler Khusraw Malik (r.1160-86 AD), although there was also a Buyid ruler who carried the same title. In any case, since at this period there was a great similarity in hilt forms between the Samanids, Ghaznavids, Buyids and even Seljuks, workshops in eastern Iranian areas are likely to have made weapons for any of the rulers or noblemen of the above dynasties. Indeed, the region of north-eastern Persia and Afghanistan had a long-standing and renowned metalworking tradition, and the skills of the silversmith turned to the production of inlaid sheet metal, principally brass (Allan 1982, p.21). It was this region that produced the finest Persian swords in this period, producing both steel for export for this purpose but also the best weaponry for which Ghor was most famed.

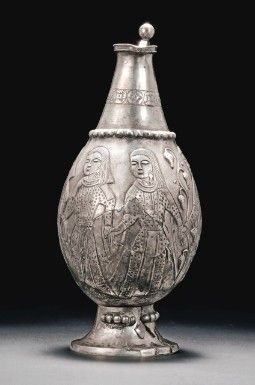

A rare and important Post-Sasanian or early Islamic silver Ewer, Persia, 8th century Estimate £300,000-£500,000

This elegant silver ewer dating from the eighth century is a very early example of Islamic craftsmanship. Of pear-shaped form and depicting six female figures dressed in lavish coats, the rare ewer presents an amalgam of styles and features associated with the early Islamic period, reflecting the important exchange of ideas and artistic motifs taking place at this time.

A rare and important post-sasanian or early Islamic silver ewer, Persia, 8th centuy - Sotheby's

of pear-shaped form standing on a tall waisted foot, the tapering neck rising to an open flattened spout, the body decorated in relief with six female figures holding hands with incised details to faces and clothing, with a tall grape vine in the backround, between two rows of repeating spherical beads, the neck with an incised band of geometric motifs, the scrolling handle surmounted by a globular thumbpiece attached to neck and body by terminals in the shape of animal-heads; 29.8cm. max. height. Estimation: 300,000 - 500,000 GBP

NOTE: This silver ewer, of elegant pear shaped form on a tall, splayed stand, decorated with six female figures wearing elegant long ornate coats holding hands, presents an amalgam of styles and features associated with the earlyIslamic period.

Within two decades of the Prophet Muhammad’s death in 632, the lands under Islamic rule encompassed a vast area, from Southern Spain in the West to North India in the East, and united multiple cultures which brought with them their own visual repertoire and traditions. It is interesting to examine the present ewer within this context and to look at the various influences involved in its production.

First, its shape finds parallels in a number of Sasanian vessels in museum collections. A silver-gilt ewer in the Metropolitan Museum (inv. no. 67.10) also has a pear-shaped body, slender mouth and tall splayed foot, with animal head terminals on its handle (illustrated in: Harper 1978, pp.60-61, no. 18). Derived from late antique forms, this shape appears to have been popular during the Sasanian period; the goddess Anahita holds a similar ewer in her hands on the rock reliefs of Khusrau II (591-628) at Taq-i Bostan (Harper 1978, p.60). Another silver-gilt ewer, now in the Shumei Culture Foundation in Japan, attributed to the late Sasanian period, around the seventh century AD, is of a similar shape, with stylised vegetal decoration throughout, and a handle also terminating in animal head motifs (illustrated in: New York, 1996, p. 78, no.32).

The design of the female figures can also be traced back to ancient forms, and features on Sasanian, Hellenistic and Roman objects as well as in Central Asian depictions. The ewer mentioned earlier, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. no. 67.10), is also decorated with dancing figures, dressed in long-sleeved costumes, but of a more suggestive, tight-fitting nature. Another ewer, in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, inv. no. S1987.117, also features such figures involved in expressive dance gestures (illustrated in: Gunter and Jett 1992, p. 194, no.35).These have been linked to Graeco-Roman “bacchantes”, the Zoroastrian goddess Anahita and her priestesses, as well as the Zoroastrian concept of den: “the soul’s accomplishments in the material world…personified as a ‘beautiful female form’” (Gunter and Jett 1992, p. 196 and Harper 1987, p.61).

Rather than presenting contradictory imagery, the links made to both of these traditions is indicative of the important exchange of ideas and artistic motifs taking place at this time. To this mixture, one must also look towards Central Asia, to the trading networks along the ‘Silk Roads’ running through the Gobi desert towards Uzbekistan and more southerly, towards Afghanistan. Frescoes from a cave originally in Kizil near Kucha, Xnjjiang, China, dateable to the fifth to sixth century, illustrate a series of figures referred to as “Tokharian Donors”, which can also be compared to those on the present vessel (now in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Museum fur Indische Kunst, inv. no. III 8426 a,b,c, illustrated in: Roxburgh 2005, pp.50-51, no.5). Even though the figures depicted are men, they are illustrated in a three-quarter pose, with their heads all looking one way, with stylised proportions in a manner comparable to those on the present ewer. Furthermore, each wears a different coat, decorated with ornamental pearl bands, crosses and of multiple colours. These give us an indication of the lavishness of the coats that the women on this ewer are wearing, their patterns and designs indicated through punched and incised motifs.

Finally, further parallels can be found in the eighth-century wall paintings of Qasr al-Hair al-Gharbi near Palmyra, Syria and in Qusair ‘Amra in Jordan, both of which are informed and influenced by the late Antique and Sasanian artistic canon (Clévenot, Degeorge 2000, pp.126-129). This ‘accumulation of images’ as described by Dominique Clévenot and Gérard Degeorge, formed “[…] a sort of artistic booty whose fate Islam had not yet decided (ibid, p.129)”. Also, it is important to mention that the grape vine arising behind the figures is similar to that on a glass beaker in the David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. no. 17/1964, and attributed to Iran or Iraq, ninth-tenth century. This early period in the formation of Islamic art is fascinating not only for its appropriation of existing artistic traditions, but also for the way that it lays the ground for the future development of Islamic art.

A ewer, dated to the ninth to tenth centuries, and attributed to the metalworking centre Basra, has a similar, pear-shaped form with a curvilinear handle indicating that this shape continued to be produced into the Abbasid period (Freer and Sackler (Smithsonian Museum), inv. no. F1945.13). Also, a similar decorative repertoire endured into the twelfth century and includes ceramic examples such as a Kashan moulded dark blue-glazed pottery jar depicting dancers in relief, dated to the twelfth century (sold in these rooms on 14 April 2010, lot 142). The catalogue entry notes the painterly qualities of its design and the rhythmic movement of the dance in which the figures are involved, formal aspects that are also visible on the present design.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F06%2F39%2F119589%2F129007933_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F83%2F41%2F119589%2F128989180_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F65%2F49%2F119589%2F128551133_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F78%2F119589%2F126903004_o.jpg)