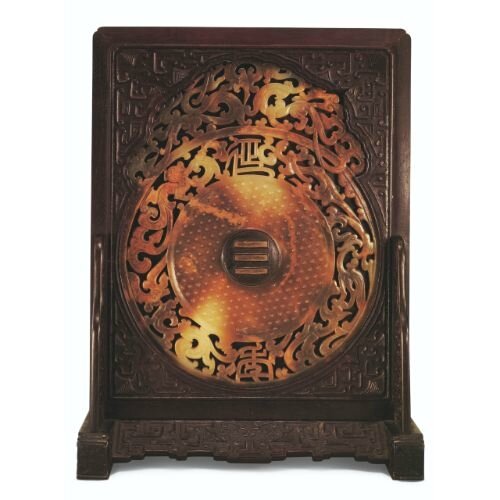

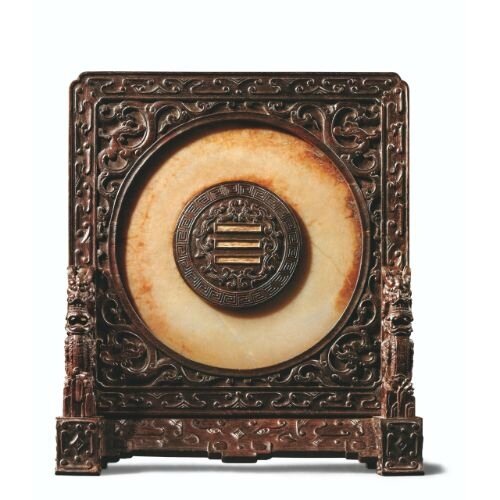

An exceptional zitan-mounted archaic jade disc, bi, Zhou dynasty, the inscription and the stand dated dated to 1775

Lot 3010. An exceptional and extremely rare dated zitan-mounted archaic jade disc, bi, Zhou dynasty, the inscription and the stand dated to 1775; height 22.8 cm., 9 in. Estimate 8,000,000 - 12,000,000 HKD. Lot sold 9,040,000 HKD. Photo: Sotheby's 2013

the smoothly patinated stone of a creamy beige tone naturally streaked with honey-brown inclusions, pierced with a large circular aperture, crisply later incised on one side in clerical script with an imperial poem praising the beauty of the treasured jade, signed Qianlong yiwei chun yuti (‘Imperial inscription in the yiwei year of the Qianlong period’, corresponding to 1775), followed by the seal de jiaqu (‘obtaining refined enjoyment’), mounted within a deftly carved zitan table screen, the front with a carved central wood boss locking into the back panel to secure the jade, detailed with a trigram qian filled in with gilt and flanked by a pair of stylised kui dragons, all enclosed within a key-fret ring, densely carved overall with archaistic scroll motifs, save for a circular medallion on the reverse, picked out in gilt with an almost identical inscription also in clerical script differing only in one character on the date Qianlong yiwei chun yue yuti, ending with the same seal de jiaqu

Provenance: By descent in the family since the early 20th century.

Note:

he Imperial ‘Zhou Dynasty Pure White Jade’ Bi

Hajni Elias

Amongst the many rulers during China’s extensive history, the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) is arguably one of the greatest in respect to his connoisseurship and appreciation of the nation’s art. He was a fanatic collector of masterpieces and had amassed an art collection of enormous scope and size that included antiques as well as contemporary pieces. His passion saw no limit, with art collectors of his time hiding their pieces or making clever copies fearing that the emperor would demand them as gifts. He was a true connoisseur as well, spending long hours into the night studying his collection, writing long colophons on his finest paintings, or composing poems for certain pieces. According to the Palace Museum scholar and expert Guo Fuxiang, amongst the emperor’s many treasures, ‘archaic jade formed an important part of his collection and his search for outstanding archaic jade saw no limit. The overwhelming majority of the archaic jade pieces were kept and used as decoration in the various halls of the palace after having been appreciated and examined by the emperor.’[1]The present Zhou dynasty (1100-256 BC) bi would have been amongst his cherished items, expertly mounted in a beautifully fashioned zitan table screen so it can be placed on a writing desk. The construction and the carving of the mounting itself represents workmanship of the highest quality only available from the Imperial Palace Workshop.

Qianlong’s thoughts on the jade bi’s are expressed in his poem titled ‘A Song for a Zhou Dynasty Pure White Jade Disk’ which is included in the Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji (Complete Poetry and Prose Composed by Emperor Gaozong of the Qing Dynasty), Siji (Fourth Collection) Qinding siku quanshu (By Imperial Order, Complete Works from the Four Treasures Library) ed., 38:39 (the summer of the bingshen year (corresponding to 1776). The poem may be translated as follows:

Its material initially mutton fat white,

The colour now is chestnut flesh yellow,

No distinguishing any cattails or mulberries here,

For absolutely no patterns are left that can be seen.Solemnly majestic, replete with primordial energy,

Radiantly glossy, suffused with muted light,

Originally made for a single lifetime’s enjoyment,

It laughs at how much collectors have paid for it ever since!

Signed: “By His Majesty, in the months of Spring in the yiwei year (corresponding to 1775)

Seal: “Achieves Elegant Appeal”

From the poem it is evident that Qianlong regarded this bi very highly. He praises it by saying that it is a work that was made for a single lifetime’s enjoyment. The emperor’s knowledge of the stone itself is also impressive and his reference to ‘cattails and mulberries’ reflects his familiarity with the shallow relief decoration frequently found on ancient jade disks. The discrepancy between the dating of the poem and the carving on the screen is interesting to note. The first couplet in the poem already appears on a much earlier imperial poem, one Qianlong wrote in 1736. Whether he ‘re-cycled’ some of his favourite phrases or lines, or the carver dated the poem erroneously remains a matter of debate.

While jade bi mounted on table screens were made to please the emperor and were beautiful objects, they also served as a reminder and keepsake of the glorious past. A court painting of the Qianlong emperor seated in one of his studios surrounded by ancient treasures, One or Two?, depicts a mounted jade bi in a wooden frame on a table with a bronze vase and albums (China. The Three Emperors 1662-1795, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005-6, cat. no. 196) (fig.1). A number of closely related zitan screens holding ancient jade disks and carved with Qianlong’s poems are known, with most preserved today in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Two screens with plain jade bi, engraved with poems and seals of the emperor are illustrated in Teng Shu-p’ing, Neolothic Jades in the Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1992, pl. 100, the stands inscribed with poems dated to 1772 and 1784, respectively. Four further examples with grain-patterned bi are included in the Illustrated Catalogue of Ancient Jade Artefacts in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1982, cat. nos. 63, 68, 188 and 189, with two of them, pls. 68 and 188, dated to 1773, and the other two dated to 1770 and 1778.

One or Two?, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong period, Palace Museum, Beijing. After: China. The Three Emperors 1662-1795, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005-6, cat. no. 196.

See also a screen with an exceptionally large bi with the inscription on the outer edge dated to 1770, first sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 10th October 1990, lot 1901, and again in these rooms, 8th April 2007, lot 603 (fig.2); and another very similar example, with an imperial poem dated to 1774, from The Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection, also sold in these rooms, 8th October 2009, lot 1808 (fig.3). Compare a further screen bearing a poem dated to 1778, included in the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London, the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935, cat. no. 2776; one sold in these rooms, 15thNovember 1989, lot 503; and one with an inscribed poem dated to 1764, also sold in these rooms, 4th November 1997, lot 1201.

Imperial Dated Zitan Mounted Archaic Jade Bi, Eastern Han Dynasty, The Inscription and the Stand Dated to 1770. Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 8th April 2007, lot 603.

Imperial Dated Zitan Mounted Archaic Jade Bi, The Inscription and the Stand Dated to 1774. Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 8th October 2009, lot 1808.

The meaning of jade bi remains an enigma; however, by the early Han dynasty it became customary to include them in the jade suits worn by imperial princes when buried. Han ritual texts and commentaries describe bi as a symbol of Heaven, and confirm its role in ritual ceremonies at the time. For example, fourteen jade bi were placed around the body of the King of Nanyue with five more laid under his jade suit. Additional discs were placed on top of the outer coffin and in between the inner and outer coffins. For further information on the use of jade bi as ritual objects during the Han period see the notes to two discs excavated at Xianggangshan in 1983 and now in the Museum of the King of Nanyue, Guangdong province, included in the exhibition The Search for Immortality. Tomb Treasures of Han China, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2012, pp. 279-282.

Under the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, jade bi continued to be associated with Heaven, and were seen as symbols of power. By commissioning the mounting of these precious objects in elaborate stands for display, the emperor was not only reminding those around him of the glorious past but also of his central power. The use of the qian trigram, one of the Eight Trigrams known as the Bagua, further re-enforces his message. The Bagua were the basis for the sixty-four hexagrams of the Zhou yi (Changes of the Zhou), the earliest form in the compilation known as the Yi Jing (Book of Changes) that was the main text providing guidance and assessment for state affairs during the Zhou dynasty. Amongst the trigrams, qian and kun, that represented yang and yin, heaven and earth, south and north, were considered the most important. These two trigrams were the ‘constants’ in the system known as the chengwu or the ‘completed procedures’. Qian was also part of the emperor’s reign title, hence it was frequently employed as a decorative motif during his reign and may be found on many imperial artefacts in his collection.

[1]See Guo Fuxiang, ‘Qianlong’s Appreciation of the Zitan Mounted ‘Dragon and Phoenix’ Bi’, By Heavenly Mandate, Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 2007, p. 48.

Sotheby's. Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art. Hong Kong | 08 avr. 2013

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F62%2F119589%2F129821675_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F11%2F119589%2F129248500_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F90%2F07%2F119589%2F129178554_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F73%2F73%2F119589%2F129177195_o.jpg)