MFA in Boston presents the U.S. debut of Samurai! Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection

Samurai! Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection. Photo: Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

BOSTON, MASS.- Fearsome warriors clad head-to-toe in decorative armor, samurai of 12th- through 19th-century Japan symbolized the power, honor, and valor of the country’s military elite. Led by omnipotent warlords, called shoguns, samurai have long fascinated the public. To provide insight into their military prowess and lifestyle, as well as the artistry of their elaborate armor, helmets, and accoutrements of warfare that bear witness to the “way of the warrior,” the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, hosts the US debut of Samurai! Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection. The exhibition, on view from April 14 through August 4, 2013, showcases more than 140 works from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection of Dallas, Texas, one of the finest holdings of samurai armor in the world. Among the works featured are 21 full suits of armor, including one formerly owned by the Yoshiki branch of the Mōri clan, a prominent family whose origins date to the 12th century. Special highlights of the exhibition include three life-size horses clad in armor to illustrate the pageantry of samurai and their mounts in battle or procession, and a dramatically lit, jewel-box display of beautifully detailed helmets and masks.

“Samurai! will transport our visitors to the world of the samurai, where ideals of personal honor and martial glory are manifested in sumptuous objects,” said Malcolm Rogers, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA. “This exhibition superbly complements the Museum’s own collection of works from Japan, which was first assembled in the late 19th century and since then has become internationally renowned.”

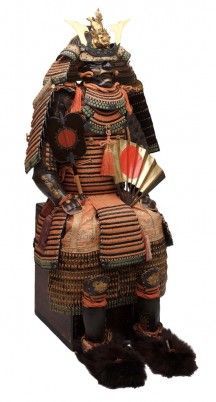

Armor of the nimaitachidō type (nimaitachidō tōsei gusoku) Muromachi period, about 1400 and mid-Edo period, 18th century. Iron, shakudō, lacing, silver, wood, gold, brocade, fur, bronze, brass, leather, and lacquer. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The collection of armor reflects the Barbier-Muellers’ interest in the samurai, a passion that has spanned 25 years and has prompted the sharing worldwide of their works through this exhibition. Previously, Samurai! was on view at the musée du quai Branly in Paris and at the Musée de la civilisation in Québec City. After its presentation in Boston, the exhibition will continue to various US-based museums. Through its traveling exhibitions and the recent opening of The Ann & Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum: The Samurai Collection in Dallas, the collection has been viewed by nearly 700,000 visitors to date.

“We are pleased to share the special selection of samurai armor suits and extraordinary helmets from our Dallas-based collection and museum with Boston,” said Gabriel Barbier-Mueller. “After a successful welcome in Paris and Québec City, we are proud that our daughter, Niña Barbier-Mueller Tollett, and curator Jessica Liu Beasley, came to install the exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. We have an extensive history with this museum and it is with great pleasure that I visit this time to both share and experience our collection with a cultural institution renowned for having the world's finest collection of Japanese art outside of Japan.”

Armor with the features of a tengu (tengu tōsei gusoku) Late Edo period, 1854. Iron, lacquer, vegetable fiber, bear fur, leather, feathers, and fabric. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Before entering Samurai!, visitors are able to preview many of the works in a dynamic presentation outside of the Ann and Graham Gund Gallery, where a video wall featuring 16 flat screens shows images animated to a soundtrack alternating delicate flute music with rhythmic drumming. Inside the gallery, they are greeted by three samurai wearing majestic suits of armor, including the 18th-century armor of the ōyoroi type (Edo period, 1615–1868). Elegant “great armor” (ōyoroi) is often constructed from more than 2,000 rectangular metal plates joined by leather or silk cording to produce a strong but flexible layer of protection. Flanking it is the armor of the yokohagidō type (Nanbokuchō, 1333–1392, and mid-Edo, 18th century, periods) bearing the butterfly crest of the Ikeda clan and the armor of the yokohagidō type (Muromachi, 1392–1568, and Edo, 1615–1868, periods). These colorful and extravagantly detailed suits were ceremonial in nature—worn in processions and during times of peace—but they evoke the kind of artistry and workmanship of armor that would have been worn in battle. Sets such as these were handed down from father to son. A ceremonial suit of armor for a boy (warabe tōsei gusoku, late Edo period, 19th century) also are on view. At a young age, the sons of samurai began military training in weapons and received strict religious and academic instruction. Around the age of 12, they would receive their first armor and sword.

Armor of the yokohagidō type (yokohagidō tōsei gusoku) Nanbokuchō period, 1333–1392; mid-Edo period; and 18th century. Iron, shakudō, gold and silver lacquer, lacing, bronze, wool, silk brocade, and bear fur. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Complementing the suits worn by samurai are an array of impressive helmets. Ranging from utilitarian to complex, they are displayed chronologically to illustrate their evolution, beginning with the earliest one in the exhibition, a large riveted helmet (ōboshi hoshibachi kabuto, Kamakura period, 1185–1333) consisting of 34 plates, each of which is riveted with protruding nails; the helmet is fitted with a neck guard made of four gold lacquered iron plates and white braiding. Also on view is a late 16th-century ridged helmet (sujibachi kabuto, late Muromachi period, 16th century) and half mask (menpō, Momoyama period, 1568–1615), and a striking helmet (zunari kabuto, mid Edo period, 18th century), made out of only three plates, which resembles a human head complete with flesh-toned lacquer for the skin and black lacquer imitating hair and eyebrows.

Full-face mask (sōmen) Edo period, 1710. Iron. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Way of the Warrior To fully appreciate the world of the samurai, the exhibition introduces visitors to their history and bushidō, the “way of the warrior.” This code of conduct incorporated martial and ethical traditions, including honesty, courage, honor, and loyalty, as well as the warrior’s acceptance of death, either at the hand of the enemy in battle, or through ritual suicide should he break the code. The history of the samurai begins in 792, when Japan ended its policy of conscripting troops. This led provincial landowners to assemble their own forces for defense, giving rise to the samurai class. By 1185, warlords became the military elite, ruling in the name of the emperor. Leading them was a shogun, commander of the most powerful family or clan. Under him were daimyo, heads of other families, who were served by samurai warriors. Through the centuries different clans vied for power. However, in 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu became shogun and established a lasting peace that extended some 250 years (Edo period, 1615–1868). During the subsequent Meiji Restoration in 1868, the emperor reasserted his authority as supreme ruler and the samurai as an official elite class was dissolved.

Ridged helmet (sujibachi kabuto) and half mask (menpō) Late Muromachi period (helmet) to Momoyama period (mask), late 16th century. Iron, copper, shakudō, gold, lacing, wood, leather, and horsehair. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Components of Armor Over the course of their long rule, the samurai clans marshaled legions of formidable warriors who cut down their enemies on foot and horseback on the battlefield. To protect the infantry and mounted samurai, armor became increasingly complex and varied, depending on its use and the status of the wearer. It also developed into an intricately designed work of art that served as a symbol of protection, ceremony, and prestige. Samurai! will illustrate the evolution of the distinctive appearance and equipment of the samurai warrior through a detailed look at the component parts of the armor, showcasing a magnificent full suit with all of its accoutrements—several surcoats, equestrian equipment, and weapons—passed down through generations for some 900 years by the powerful Mōri, a prominent daimyo clan.

Flame helmet (kaen kabuto) representing the flaming jewel (hōju no tama) Early Edo period, about 1630. Iron, lacquer, lacing, gold, and bronze. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Samurai armor, particularly the ōyoroi type, which reached its peak during the Kamakura period (1185–1333) represented the ultimate in craft artwork. Richly decorated rectangular leather or iron plates, lacquered and laced together with either leather or silk cords, covered most of the wearer’s body. The ōyoroi suit, worn by warriors on horseback, consisted of a chest plate (dō) adorned with beautifully decorated leather; shoulder guards (sode) embellished with metal and cord; fabric and metal sleeves (kote); paneled skirting (kusazuri); thigh protection (haidate); shin guards (suneate); and shoes (kutsu) made of bear fur, horsehair, or leather. The warrior’s head was protected by a helmet (kabuto) made of trapezoidal iron plates joined together by rivets, upon which decorative embellishments were added to personalize the helmet, indicate the samurai’s clan, or identify commanders during the chaos of battle. Flanged panels (shikoro) protected their necks, and on their faces, they wore decorative metal masks, such as the frightening full face mask (sōmen, Edo period, 1710), which takes the form of a Buddhist guardian deity. A suit of armor worn in combat could weigh up to 65 pounds and was made for a warrior measuring almost five feet tall. Completing the set were additional articles, including a sleeveless surcoat (jinbaori), worn over the armor for extra protection. Many were made of wool, cord, and brocade. One of the most beautiful surcoats on display in the exhibition is from the Edo period, fabricated in red wool with cream-colored silk lining the interior; the back of the garment is decorated with a white paulownia mon (heraldic family crest) of the Mōri family.

Armor of the yokohagidō type (yokohagidō tōsei gusoku) Early to mid-Edo period, 17th–18th century. Iron, leather, gold, wood, fur, hemp, and lacing. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Creating samurai armor was a highly specialized art form overseen by an armorer, who recruited a team of blacksmiths, softmetal (gold and copper) craftsmen, leather workers, braid makers, dyers, painters, and other artisans. The armor they produced protected the wearer and incorporated motifs reflecting samurai spirituality, folklore, and nature. Nine main schools were established, and in the Edo period (1615–1868), armorers were elevated to the rank of artists. The Myōchin school, which is well represented in the Barbier-Mueller collection, still exists and has been maintained by the same family for generations.

Late 16th- and early 17th-century armor of the okegawado type. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann & Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Armor was crafted depending on whether the samurai fought on foot or horseback and what types of weapons were in use at the time. Spears, arrows with quivers, swords, and a matchlock gun will be on view in the exhibition. Until the end of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), bows and arrows were the samurai’s primary weapons. During the Nanbokchō and Muromachi periods (1333–1392 and 1392–1568), more battles requiring hand-to-hand combat made lances and swords the more effective weapons of choice until the introduction of the matchlock gun in 1543 by “southern barbarians” (nanban), Portuguese mariners who brought firearms with them when they landed in southern Japan. Their influence, and that of the Dutch, can be seen in a variety of masks and helmets in the exhibition. European army equipment eventually impacted the styles of Japanese armor, and construction had to adapt to protect against the new weapon introduced by the Portuguese.

Horse armor (bagai) with horse mask (bamen) and horse tack (bagu) Early to mid-Edo period, 17th–18th century. Leather, gold, fabric, wood, horsehair, and lacing. Armor of the tatehagidō type (tatehagidō gusoku), Early Edo period, 17th century. Iron, leather, gold, and fur. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann & Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Samurai and His Horse The spectacle of high-ranking samurai dressed in full regalia for battle, procession, and ceremony comes to life in a display of three warriors on horseback. Of particular note is armor of the tatehagidō type (early Edo period, 17th century), shown with horse armor (bagai), a horse mask (bamen), and horse tack (bagu, early to mid-Edo period, 17th–18th century). Horse armor was made of small tiles of pressed leather lacquered in gold and sewn onto cloth. A mask crafted of boiled leather that was shaped and lacquered to represent a stylized horse or dragon protected the horse’s head. The saddle was made of lacquered, decorated, or inlaid hardwoods, and saddle pads protected the horse from the heavy metal stirrups. The samurai were accomplished mounted archers, outfitting their horses with wide stirrups made of iron, wood, and copper or silver; these served as sturdy platforms on which the archers could stand and shoot. Before the 17th century, samurai horses did not wear armor. Subsequently, the armoring of horses conveyed the prestige and power of their owners during ceremonies that paid tribute to highranking leaders or marked special occasions. To dramatize the pageantry of these events, five suits of samurai armor in procession also are on view near the mounted horses.

Frontal crest (maedate) Mid-Edo period, 18th century. Lacquer, gold, and horsehair. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Armor as Works of Art When not in use, samurai armor would be showcased for guests to see in the shoin, or special reception room of a daimyo’s home, on the 11th day of the first month of each year. A highlight of Samurai! is the presentation of helmets and suits of armor as not only symbols of power and authority, but also as beautiful works of art. Exquisitely decorated helmets, such as Flame helmet (kaen kabuto) representing the flaming jewel (hōju no tama, early Edo period, about 1630), are seen in a dramatically lit, jewel-box display, one of numerous helmets adorned with fanciful shapes, including horns, shells, bamboo, and Buddhist iconography.

“Arts of the samurai have long attracted audiences here at the Museum and this exhibition provides an unparalleled opportunity for our visitors to experience striking works of tremendous artistry,” said Anne Nishimura Morse, the MFA’s William and Helen Pounds Senior Curator of Japanese Art. “We hope that visitors will also enjoy viewing works from the Museum's Art of Japan collection on display in our galleries.”

Armor of the nuinobedō type (nuinobedō tōsei gusoku) Late Momoyama and Edo period, second half of 16th century; and 17th–18th century. Iron, gold, lacquer, and lacing. Photograph by Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The exhibition concludes by showcasing three magnificent suits of armor that illustrate how these outfits become increasingly decorative during the 250 years of peace that marked the end of the samurai’s dominance. Included among them is the armor of the nimaitachidō type (nimaitachidō tōsei gusoku, mid-Edo period, 18th century), which belonged to a daimyo of the Matsudaira family, once one of the wealthiest in Japan. The suit is constructed of iron, shakudō, silk, silver, wood, gold, fur, bronze, brass, and leather. The exquisitely crafted helmet supports two stylized bronze horns and a lacquered wood shishi (lion). Equally impressive is the armor of the okegawadō type (okegawadō tōsei gusoku, late Momoyama to early Edo period, late 16th-century, early 17th century), a suit of armor featuring a helmet with three six-foot-tall gilt feathers, which captures the high drama of the fully outfitted samurai warrior in all of his glory.

Ridged helmet (sujibachi kabuto) and half mask (menpō) Signed Echizen no kuni Toyohara jū Bamen Sadao (Sadao of the Bamen School, living in Toyohara, Echizen province) Late Muromachi period (helmet) to Momoyama period (mask), late 16th century Iron, copper, shakudō, gold, lacing, wood, leather, horsehair. Photo: Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Samurai warriors on horses made of fiberglass and steel.. Photo: Brad Flowers. © The Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F45%2F84%2F119589%2F128381154_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F25%2F119589%2F128370615_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F95%2F119589%2F126875799_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F72%2F119589%2F122505070_o.jpg)