Mesopotamia: Inventing Our World opens at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto

Statue of Ashurnasirpal II. Magnesite (statue), red limestone (base), Nimrud, Temple of Ishtar Sharrat-niphi, 875 - 860 BCE. Statue H : 113cm, W : 32cm, D : 15cm © The Trustees of the British Museum.

TORONTO.- The Royal Ontario Museum is the sole Canadian venue to host Mesopotamia: Inventing Our World during its international tour. This impressive exhibition showcasing an innovative society makes its North American debut on Saturday, June 22, 2013 in the Garfield Weston Exhibition Hall on Level B2 in the Museum’s Michael Lee-Chin Crystal. On display only until Sunday, January 5, 2014, the ROM’s engagement of Mesopotamia: Inventing Our World is presented by RSA Insurance.

Exploring over 3,000 years of accomplishments of this ancient civilization to reveal the significance many still have on our lives today, Mesopotamia features over 170 priceless objects from the esteemed holdings of the British Museum. These artifacts, most of which have never been seen in Canada, are augmented by iconic objects from the ROM’s own renowned collections and other leading institutions, including the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Museum, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum, Philadelphia), and Detroit Institute of Arts.

Mesopotamia is presented by the British Museum in collaboration with the ROM. The curator of the internationally touring exhibition is Sarah Collins, the British Museum’s curator for Early Mesopotamia. She says, “The British Museum is highly fortunate to have rich Mesopotamian collections as a result of British archaeological excavations undertaken in the past. As custodian of these ancient objects, it is a privilege to make them available to as wide an audience as possible – both in London and internationally. I am very happy to work with the ROM to present some of Mesopotamia’s many achievements. While it is challenging for us today to feel a connection to people of a civilization that existed thousands of years ago, I hope that exhibition visitors will discover aspects of Mesopotamian life and legacy that relate to their own lives.”

Janet Carding, the ROM’s Director and CEO states, “We are pleased to collaborate with our colleagues at the British Museum to uncover this intriguing ancient civilization. Mesopotamia has it all — longevity, noteworthy accomplishments, and a certain amount of mystery. We look forward to sharing with our visitors this dramatic story told through remarkable objects.”

Dr. Clemens Reichel, Professor of Mesopotamian Archaeology at the University of Toronto and Associate Curator for the Ancient Near East in the ROM’s Department of World Cultures, is the Museum’s expert on ancient Mesopotamia. As an experienced field archaeologist who recently returned from a trip to Iraq, he is pleased that his area of research is highlighted in the exhibition — but cautions against a narrow view of this ancient society. Dr. Reichel stresses, “Mesopotamia was a true frontrunner, with great cities of sizes not achieved by Paris or London until the Industrial Revolution; empires that controlled most of the known world of that time; and technological achievements still shaping our lives. However, Mesopotamia was also ruled by kings who were as brutal as they were brilliant, whose rise to power was as stellar as their demise was cataclysmic. With the ancient society reflecting some of mankind’s earliest ‘highs’ and ‘lows’, we are still able to learn from Mesopotamia.”

Background Geographically

Mesopotamia (from the Greek “[land] between the Rivers”) encompasses present-day Iraq, north-eastern Syria, and south-eastern Turkey. Urban civilization originated in the area, accompanied by the establishment of the first cities and complex forms of social organization and economic activity. Significant developments during this period include the invention of writing, long-distance communication, trade networks, and the first empires. Sophisticated art and literature began and flourished concurrently with remarkable intellectual, spiritual, and scientific advances.

Mosaic column drum - Shell, pink limestone, and black shale c. 2500 BC From Tell al-‘Ubaid, Ninhursag Temple H 59cm, Diam. 31cm BM 115328 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Exhibition Introduction

That the people of Mesopotamia were great innovators is established immediately on entering the exhibition. This assertion is effectively illustrated throughout the space, allowing visitors to discover their personal connections to the ancient civilization. First encountered in this Introduction area is a series of six installations or “cubes”. Interspersed throughout the exhibition and employing several media, each cube powerfully connects ancient Mesopotamian innovation to contemporary life. While Mesopotamia addresses numerous benchmarks of the society’s social and technological developments, including the Agricultural Revolution and the development of village economies, its main focus is on the emergence of cities and states in ancient Sumer (4000 - 2000 BCE); the Assyrian World Empire (1000 - 600 BCE); and the rise and fall of Babylon (600 - 540 BCE).

Sumer

During the third millennium BCE, southern Mesopotamia consisted of two main regions — Sumer, in the far south and Akkad, to the north. A common culture of shared beliefs and artistic traditions united southern Mesopotamia for much of the period between 3000 and 2000 BCE. One of the most significant advancements taking place in Mesopotamia was the emergence of the city. While large towns had evolved before 3500 BCE, there was a massive change in scale around this time. The largest city was Uruk and, by about 2600 BCE, it displayed the elements of the period’s important centres: administrative buildings, residential areas, streets, canals and, the most visible feature, cultic high terraces with temples.

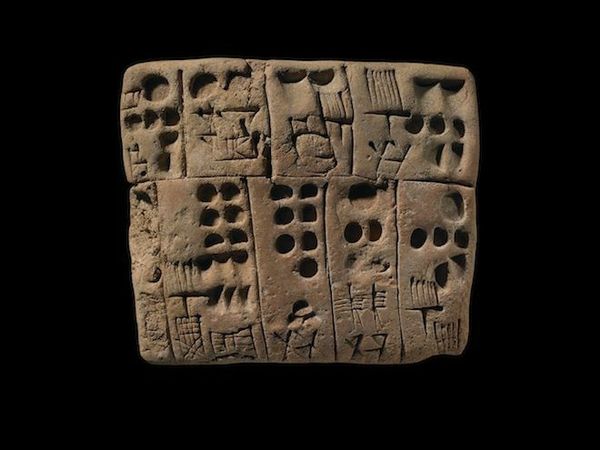

True writing began in Mesopotamia, with the earliest script found on clay tablets excavated in the cities of Uruk and Susa (southwest Iran) dating to about 3300 BCE. These cuneiform tablets, several of which are included in this section, provided important administrative information, such as the tracking of quantities of malt and barley or oxen.

From 1922 to 1934, British archaeologist C. Leonard Woolley directed excavations at Ur on behalf of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum. This city was inhabited from about 6000 BCE until the 4th century BCE and was an important political, religious, and economic centre. For a time, Ur was the capital of a state that dominated most of Mesopotamia. Some of the most spectacular discoveries were found in the Royal Cemetery, dating to the Early Dynastic Period (2600-2300 BCE). Predating the Tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt by more than a thousand years, 16 graves were identified as “Royal Tombs” due to their construction, the abundance of grave goods, and the bodies of numerous soldiers, servants, and palace ladies who willingly (or, perhaps, unwillingly) followed their masters or mistresses into their afterlives. The jewellery and other gold objects worn by the women, including elaborate headdresses, necklaces, and bracelets made of lapis lazuli, gold, and carnelian Headdress with gold leaves - Gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian c. 2500 BCE From the King’s Grave BM 121483 © The Trustees of the British Museum. are among the exhibition’s highlights.

Other notable artifacts displayed in this section, exclusively seen in the ROM’s engagement, include two objects from the Royal Cemetery: the magnificent “Ram in the Thicket,” a delicate figure comprised of silver, gold foil, lapis lazuli, and shell, and the massive “Great Lyre” featuring a gold-plated bull’s head and inlays of precious materials — both on loan from the Penn Museum. The “Ram”, displayed during the first half of the exhibition’s engagement, is to be replaced by the “Lyre” for its second half. An exquisitely carved statuette of Gudea, a ruler of the city state of Lagash, is also seen in this section. On loan from the Detroit Institute of Art, it is one of the finest pieces of sculpture from the Neo-Sumerian period (2150 – 2000 BCE).

Assyria

Named for the ancient city of Ashur, Assyria was located in northern Mesopotamia on the Tigris River. For many centuries, Ashur was little more than a city-state. After 1350 BCE, however, Assyria emerged as a political and military power, becoming the dominant world power during the Neo Assyrian period (1000-612 BCE). At its height (about 660 BCE), this empire controlled an area covering Iraq, Syria, Israel, Egypt, and parts of Iran and Turkey. Several of its kings founded the new capitals at Nimrud, Khorsabad, and Nineveh. Of central importance in the administration of the Assyrian empire, in his religious role the king was the people’s direct mediator to the great gods of Assyria while politically, he was head of the state and the military. One of the most famous Assyrian kings was Ashurnasirpal II (883 - 859 BCE), represented in the exhibition by a statue made of magnesite. This figure is a rare surviving example of Assyrian sculpture in the round. Other kings represented include Tiglath-Pileser III (744-727 BCE), Sargon II (721-705 BCE), Sennacherib (704-681 BCE), and Ashurbanipal (669-627 BC).

Assyrian cities were dominated by large palaces adorned with elaborately carved stone reliefs. Artifacts from Nimrud and Nineveh’s most famed palaces dominate this section. Some of the reliefs’ scenes recount military achievements, deportations, and the punishment of rebels, while others show cultic performances involving the king. By highlighting the king’s achievements, these scenes also convey strong ideological messages: submitting to Assyria’s throne brings peace and prosperity, while rebellion results in defeat and annihilation.

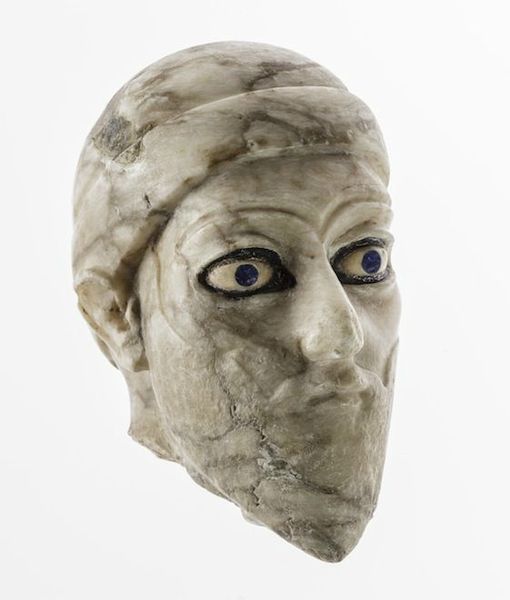

Babylon was located on the Euphrates River in what is now central Iraq. First referenced in cuneiform texts in the third millennium BCE, the city rose to prominence after 2000 BCE and controlled most of Mesopotamia by 1755 BCE. The armies of King Hammurapi, Babylon’s most famous ruler, who reigned from 1792 – 1750 BCE, united southern and central Mesopotamia under Babylonian rule. Hammurapi is best known for the collection of a set of laws named after him (Codex Hammurapi). Displayed in this section is a life-sized copy of the legendary Hammurapi Stela, on loan from the Penn Museum. The “Bismaya Head”, an elaborately carved alabaster sculpture of a ruler or tribal leader, on loan from Chicago’s Oriental Institute Museum, is another section highlight.

Following the fall of the Assyrian empire in 612 BCE, Babylonia became the dominant power of the Ancient Near East. A 3-D fly-through of Babylon, then the world’s largest city, features the city-state’s famed landmarks such as the Tower of Babel, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and the Ishtar Gate is an exciting component of this section. Artifacts here include the ROM’s Striding Lion Terracotta Relief, once adorning the throne room façade of the palace of King Nebuchadnezzar II (605 - 562 BCE) — where Alexander the Great later died.

Striding Lion relief. Terracotta. Babylon, Southern Citadel, throne room facade of the palace of King Nebuchadnezzar II, 605 - 562 BCE. H: 122cm, W: 183cm, D : 8cm. 937.14.1 Photo: © ROM 2013.

Serpentine seal, engraved with the gods before 2300 to before 2150, from Ur. British Museum Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved..

Head of a King, ca. 2100 BCE, Bismaya (ancient Adab), Iraq. Oriental Institute Museum A173. University of Chicago © 2010 The Oriental Institute, The University of Chicago

The early administrative fender book, 3300 BC to 3000 years before, probably from Uruk. British Museum. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Gold cup with spout. British Museum. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Ram in the Thicket (or Ram Caught in a Thicket) (Mesopotamian, ca. 2650-2550 B.C.). Found in the "Great Death Pit" at Ur. Gold, silver, lapis lazuli, copper, shell, red limestone and bitumen. H. 42.5 cm. © University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Bronze head of a king. Media and others were given a sneak preview of the Mesopotamia: Inventing Our World exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum. The exhibit opens June 22 and runs till Jan. 5, 2014. (Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail)

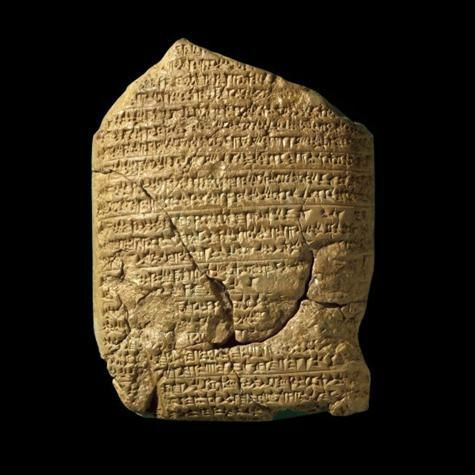

A record of Nebuchadnezzar's successes. Media and others were given a sneak preview of the Mesopotamia: Inventing Our World exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum. The exhibit opens June 22 and runs till Jan. 5, 2014. (Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail)

The Killing of Lions: The carving shows the king of a great city vanquishing the king of the wild, which represents order triumphing over chaos. (FRED LUM/The Globe and Mail)

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet VI, tells the story of the fifth king of Uruk, which is in modern-day Iraq. (FRED LUM/The Globe and Mail)

Dying lion, about 645 to 640 years before, from Nineveh North Palace.

Limestone votive statue of a woman, c. 2500 BC. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Tablet - Nebuchadnezzar and Jerusalem. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Tablet - Steatite foundation. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Woman’s headdress. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Gold and lapis lazuli collar or choker. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved

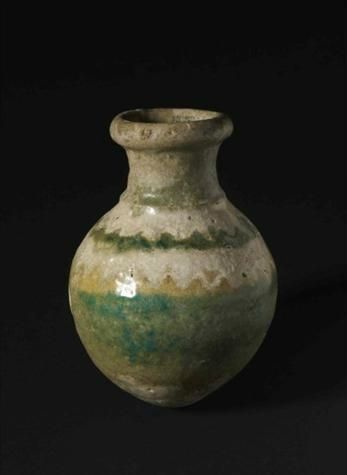

Glazed ceramic jar. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Jewellery set of cylinder and stamp seals. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Glazed wall plaque from a temple. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Bronze lion weight. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Ivory panel showing a woman at a window. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Man's headdress. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Pair of gold double-crescent earrings. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Tablet - Stela of Ashurbanipal. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_b2fe42_telechargement-9.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_af8bb4_telechargement-6.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_b6c4a6_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_981d5f_h22891-l367411650-original.jpg)