Exhibition in Edinburgh sheds new light on Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings

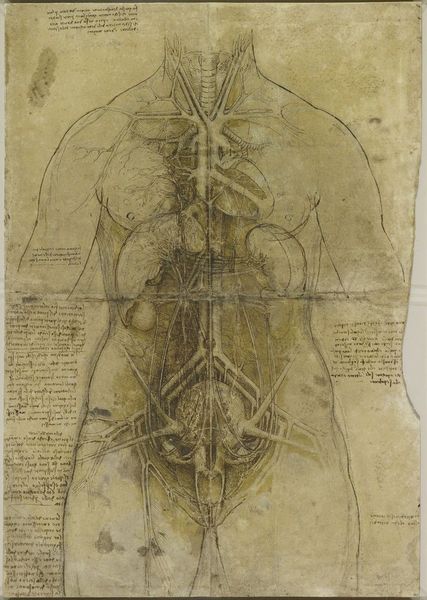

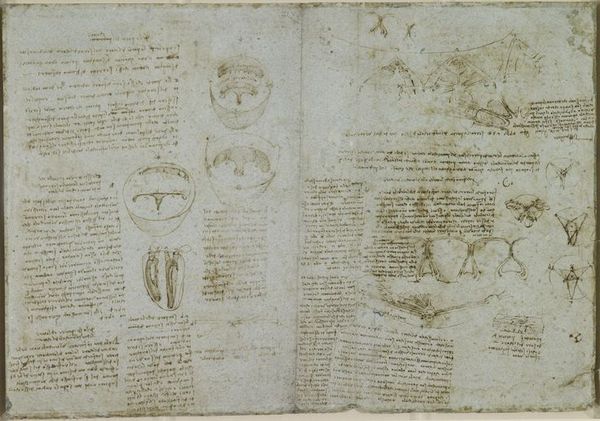

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The major organs and vessels. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

EDINBURGH.- Almost 500 years after Leonardo da Vinci’s death, an exhibition that sheds new light on the his groundbreaking studies of the human body opened this Friday at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse as part of the Edinburgh International Festival. Long renowned as one of the finest artists of the Renaissance, Leonardo was also one of the greatest anatomists the world has ever seen. For the first time ever, the pages from Leonardo’s anatomical notebooks have gone on display alongside 21st-century medical imagery, revealing how Leonardo’s work foreshadowed modern techniques, such as MRI scans and 3D computer modelling, to an astonishing degree.

Of the 30 works on display, more than half are exhibited in Scotland for the first time. Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Man (2 August – 10 November) includes 18 of Leonardo’s finest sheets, collectively known as ‘Anatomical Manuscript A’. Produced during the winter of 1510-11, the pages are crammed with more than 240 individual drawings and notes running to more than 13,000 words in the artist’s distinctive mirror-writing. Here Leonardo illustrated almost every bone in the human body and many of the major muscle groups. Manuscript A has never before been displayed in its entirety in the UK.

Leonardo initially began researching the human body to ensure that his paintings were as ‘true to nature’ as possible. But the artist soon conceived the idea of writing and publishing an illustrated treatise on anatomy. Between 1507 and 1513 he dissected more than 30 human corpses. He filled hundreds of pages of his notebooks with detailed studies of the organs and vessels, the bones and muscles, and the heart, the like of which had never been seen before. On his death in 1519, Leonardo’s anatomical studies remained unpublished among his private papers, and they were effectively lost to the world for hundreds of years. Had they been published at the time, they would have been the most influential work on the human body ever produced.

Computer modelling, CT and MRI scans, and 3D film today allow the body to be explored in minute detail and from any angle. But at the outset of Leonardo’s career, anatomical illustration was in its infancy, and so the artist had to develop a range of new illustrative techniques to convey the three-dimensional moving form of the body on a static sheet of paper. He used skills that he had acquired through other work; from architecture, he employed the principles of elevation, plan and section; and from engineering, he took the ‘exploded view’ to portray structure and movement, pulling elements apart to show how they fit together. For example in c.1510-11, using these techniques, Leonardo produced the first accurate depiction of the spine in history. This is replicated in the exhibition by modern computer modelling.

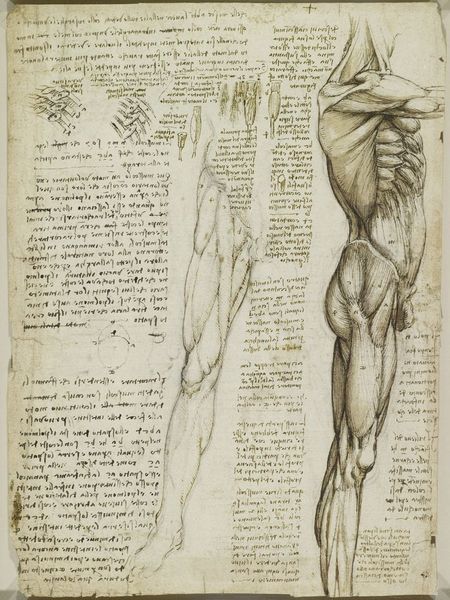

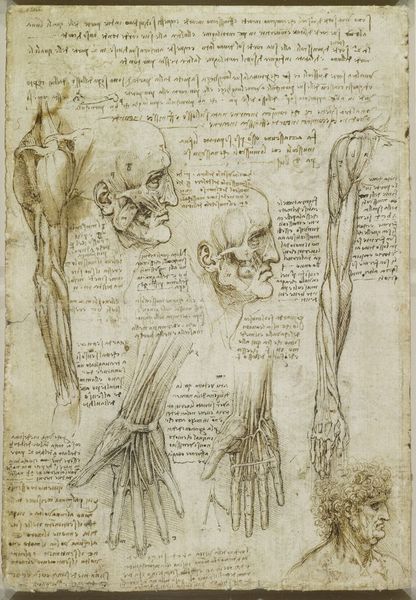

On one masterful sheet, Leonardo demonstrates the layered structure of the hand through four dissections, beginning with the bones before adding the deep muscles of the palm, and then applying the first and second layers of tendons. Today, an animated computer simulation replicates the artist’s layering technique and reveals that modern-day anatomists, when trying to understand the intricacies of this structure, use exactly the same sequence of images as Leonardo did 500 years earlier.

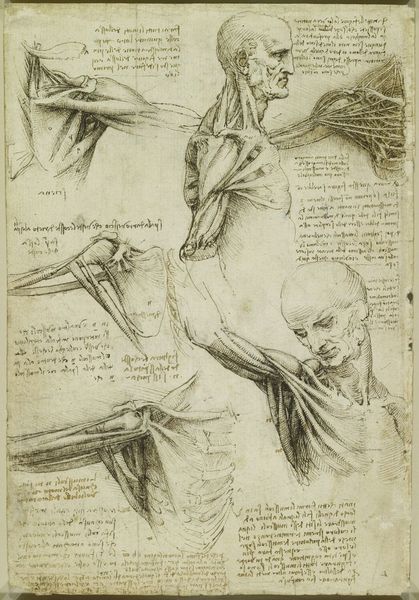

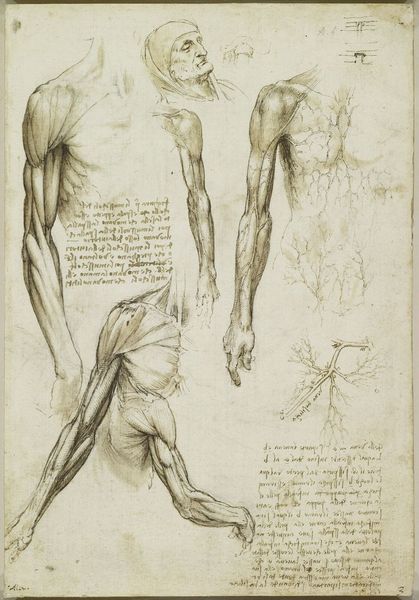

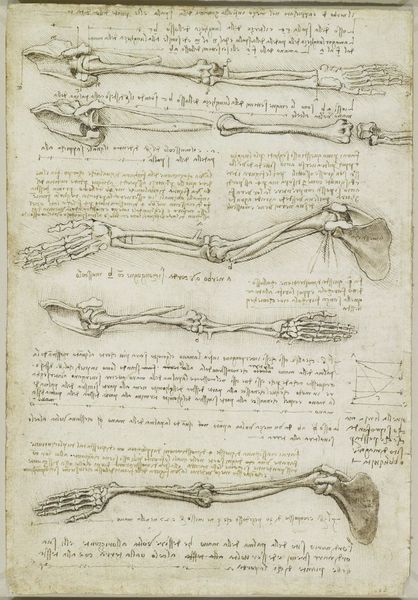

On a pair of sheets Leonardo recorded the muscles of the shoulder and arm in eight views through 180 degrees, rotating the body to capture the full three-dimensional complexity of the structure in a two-dimensional drawing. Leonardo was fascinated by the shoulder and studied it at different levels of dissection, in different poses and from different angles. A 3D film in the exhibition shows a dissected shoulder in rotation, revealing the incredible accuracy of Leonardo’s studies.

Other exhibition highlights include Leonardo’s notes from his post-mortem dissection of a 100-year-old man (conducted c.1508), in which he gives the first accurate descriptions of cirrhosis of the liver and narrowing of the arteries in the history of medicine. His beautiful study of a child in the womb (c.1511) is displayed alongside a 3D ultrasound scan of a foetus. Although Leonardo’s drawing was ultimately based on the dissection of a pregnant cow, it is clear from the ultrasound that his intuitions about the posture of the child in the uterus were correct.

Leonardo’s last and greatest anatomical campaign was an investigation of the heart. Dissecting the hearts of oxen, he recorded the form of the chambers, valves and coronary vessels. He made a glass model of the aortic valve to study the flow of blood, but it was not until the 1980s that the pulsing image of a real-time MRI scan allowed anatomists to confirm that Leonardo’s description of the heart’s action had been almost entirely correct. Visitors to the exhibition will be able to compare an MRI scan of a beating heart with Leonardo’s work. Leonardo came very close to discovering the circulation of the blood, a century before William Harvey – but it was with the heart that his anatomical investigations came to an end.

All of Leonardo’s surviving anatomical studies arrived in England in the 17th century, bound into a single album as part of a group of almost 600 drawings by the artist. The album was probably acquired later that century by Charles II and has been in the Royal Collection since at least 1690. The drawings were removed from the album for conservation reasons, but visitors can see the original 16th-century binding in the exhibition.

Exhibition curator Martin Clayton of Royal Collection Trust said, ‘This is the first time that Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings have been displayed alongside their modern-day counterparts. It’s incredibly exciting to discover how Leonardo’s investigations 500 years ago foreshadowed the work of today’s leading anatomists to an astonishing degree.’

Exhibition collaborator Peter Abrahams, Professor of Clinical Anatomy, Warwick Medical School UK said, ‘In many ways Leonardo predicted the 20th-century revolution in various medical imaging techniques. His use of cross sections and slices to show deep internal structures within the body foreshadowed the modern techniques of CT and MRI scanning. The anatomical accuracy of Leonardo’s drawings has rarely ever been surpassed, and I still use them to teach surgeons and medical students today.’

Director of the Edinburgh International Festival, Jonathan Mills, said, ‘The Festival is delighted to be working with Royal Collection Trust on this special exhibition. In a year when the Edinburgh International Festival is focusing on the myriad of ways in which technology seizes and shifts the imaginations of artists, there is no better example of that than the genius of Leonardo da Vinci and his sophisticated and poetic understanding of the human condition.’

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The viscera of a horse. Verso: The hemisection of a man and woman in the act of coition. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

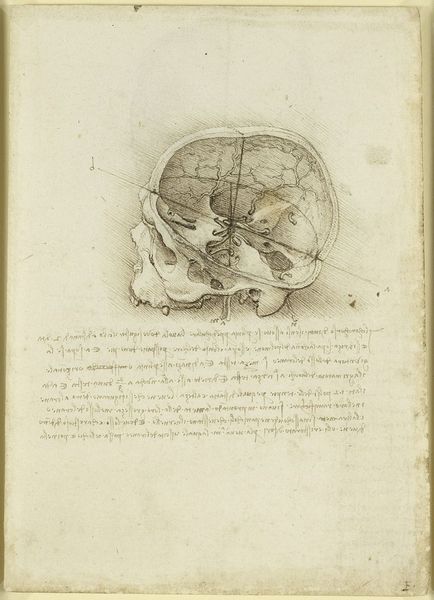

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The cranium sectioned. Verso: The skull sectioned. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The veins of the arm. Verso: Notes on the death of a centenarian. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

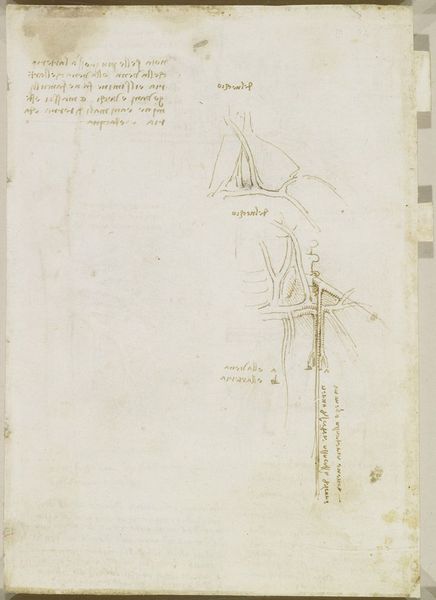

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The vessels and nerves of the neck. Verso: The vessels of the liver. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The heart compared to a seed. Verso: The vessels of liver, spleen and kidneys. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The brain. Royal Collection Trust

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The cardiovascular system and principal organs of a woman. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The superficial anatomy of the shoulder and neck. Verso: The muscles of the shoulder. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The bones and muscles of the shoulder. Verso: The superficial anatomy of the shoulder and neck. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The muscles of the shoulder and arm. Verso: The muscles of the shoulder and arm, and the bones of the foot. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

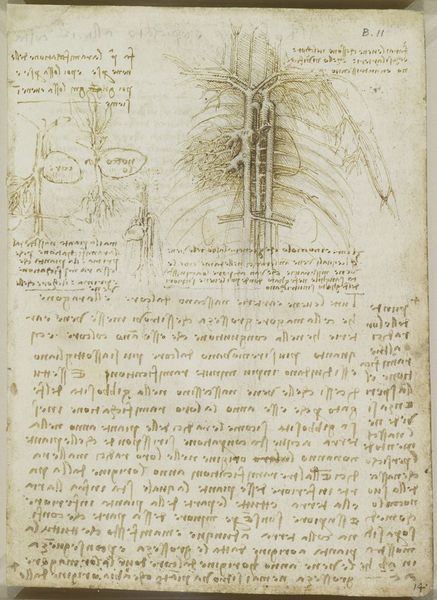

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The muscles of the upper spine. Verso: The muscles of the upper spine. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The muscles of the leg. Verso: The muscles of the trunk and leg. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

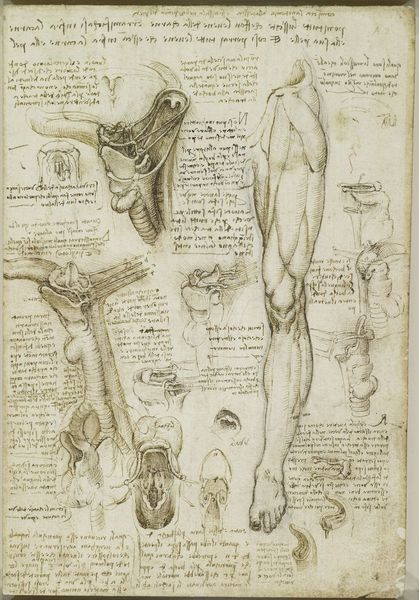

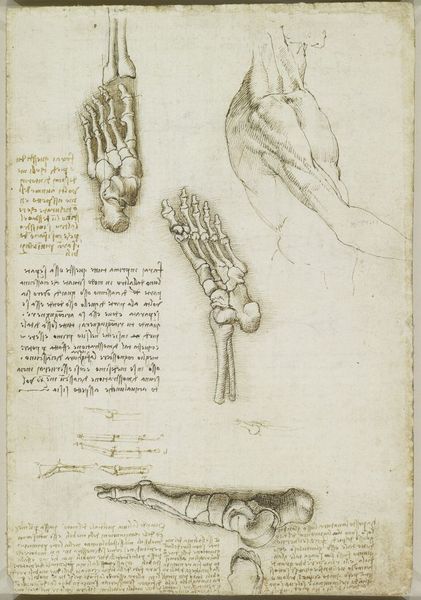

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The throat, and the muscles of the leg. Verso: The bones of the foot, and the muscles of the neck. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The muscles of the arm, and the veins of the arm and trunk. Verso: The muscles of the shoulder, arm and neck. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The bones and muscles of the leg. Verso: The muscles of the shoulder, arm and neck. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The bones of the foot. Verso: The bones and muscles of the arm. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The bones of the arm and leg. Verso: The surface anatomy of the shoulder. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The surface anatomy of the shoulder and arm. Verso: The vertebral column. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The bones, muscles and tendons of the hand. Verso: The bones of the hand. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The skeleton. Verso: The muscles of the face and arm, and the nerves and veins of the hand. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

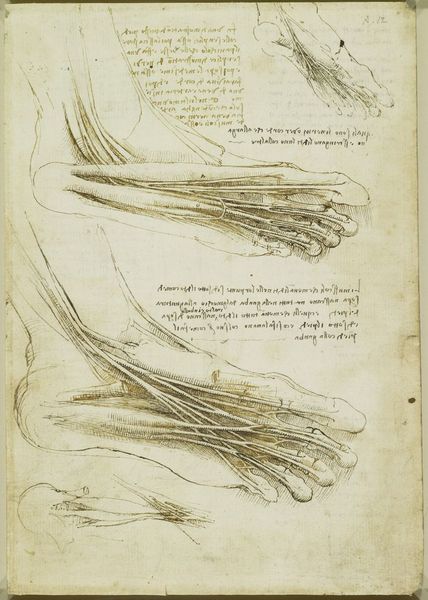

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The muscles of the leg, and the intercostal muscles. Verso: The muscles of the foot. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The bones of the foot, and the shoulder. Verso: The veins and muscles of the arm. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The muscles and tendons of the sole of the foot. Verso: The muscles of the lower leg. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The tendons of the lower leg and foot. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The muscles and tendons of the lower leg and foot. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Recto: The foetus in the womb. Verso: Notes on reproduction, with sketches of a foetus in utero, etc. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The ventricles, papillary muscles and tricuspid valve. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). The aortic valve. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). Blood flow through the aortic valve. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F02%2F119589%2F129147865_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F12%2F119589%2F122078065_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F69%2F72%2F119589%2F120628255_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F47%2F119589%2F117900055_o.jpg)