Free download MET's publications about Chinese Art

Along the Ancient Silk Routes: Central Asian Art from the West Berlin State Museums. Härtel, Herbert, and Marianne Yaldiz (1982)

Along the Border of Heaven: Sung and Yüan Paintings from the C. C. Wang Collection. Barnhart, Richard M. (1983)

Along the Border of Heaven: Sung and Yüan Paintings from the C. C. Wang Collection. Barnhart, Richard M. (1983)From the tenth century to the end of the Manchu Ch'ing dynasty early in this century, the dominant concern of the Chinese painter has been the natural world of landscape, trees and rocks, birds and animals, flowers and bamboo— "the myriad phenomena occasioned by consciousness," in the words of the eleventh-century art historian Kuo Jo-hsü. The older figure and narrative traditions remain vital for a time, during the period of the Sung (960–1279) and Yüan (1279–1368) dynasties, then rapidly declined, becoming the concern only of journeymen artisans and court chroniclers.

It is this watershed of Chinese art from the tenth through the fourteenth centuries, when the new art of landscape painting and bird and flower painting was born and the ancient traditions had their final flowering, that provides the historical context for this book. No attempt has been made, however, to provide a full historical background for the works discussed. A selection of some of the finest Sung and Yüan paintings from the collection of Wang Chi-ch'ien provides the only focus. These works have been grouped by subject matter and period, described and analyzed, and allowed to form their own network of relationships. Inevitably, there are imbalances and gaps. It is remarkable, nonetheless, that so complete a survey of Sung and Yüan painting can be written based on the collection of one connoisseur-collector. Few great museums outside of China could offer so rich and complete a selection.

Along the Riverbank: Chinese Paintings from the C. C. Wang Family Collection. Hearn, Maxwell K., and Wen C. Fong (1999)

Along the Riverbank: Chinese Paintings from the C. C. Wang Family Collection. Hearn, Maxwell K., and Wen C. Fong (1999)

This publication celebrates the promised gift to The Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Oscar Tang family of twelve major works from the C. C. Wang Family Collection, one of the great private collections of Chinese old master paintings to be assembled in the twentieth century. Ranging in date from the tenth to the early eighteenth century, these works significantly extend the Museum's holdings and reveal those areas of Chinese painting of particular interest to Mr. Wang. An accomplished artist, Ch'i-Ch'ien Wang, a resident of New York City since 1949, began collecting paintings in Shanghai more than seventy years ago. Works from his collection, long known to Western scholars and connoisseurs, are now in many American public institutions and universities. The Metropolitan owns some sixty works formerly in this collection, the twelve presented here constituting the most recent addition to the Museum's holdings from this source. Along the Riverbank is published on the occasion of the exhibition "The Artist as Collector: Masterpieces of Chinese Paintings from the C. C. Wang Family Collection," which includes most of the works acquired by the Museum from Mr. Wang since 1973.

Among the twelve paintings presented here is the famed Riverbank, attributed to the tenth-century master Dong Yuan (active 950s–60s), one of the patriarchs of the scholarly Southern school of landscape painting. It is generally recognized as one of the rare extant paintings marking the inception of the monumental landscape tradition in China. An essay by Wen C. Fong presents an in-depth stylistic analysis and contextual history of the painting. A physical analysis of the work is also included.

An extended essay by Maxwell K. Hearn examines all twelve paintings. The major examples of landscape art include Simple Retreat, by the renowned scholar-artist Wang Meng (1308–1385), who drew inspiration from the vision of landscape created by Dong Yuan and other tenth-century painters. In addition to landscapes, the collection features several important figure paintings, including Palace Banquet, by an unknown Academy painter of the Southern Tang dynasty (967–75) and a long monochrome narrative by Zhao Cangyun, a late-thirteenth-century survivor of the Mongol conquest. The genre of flower-and-bird painting is represented by Mandarin Ducks and Hollyhocks, a pictorial metaphor of marital happiness by the leading early Ming academic master Lü Ji (active late 15th century), and by Two Eagles, a defiant symbol of political resistance by Bada Shanren (1616–1705), a member of the Ming royal house who lived through the occupation of China by the Manchus.

Ancient Chinese Art: The Ernest Erickson Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hearn, Maxwell K. (1987)

Ancient Chinese Art: The Ernest Erickson Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hearn, Maxwell K. (1987)

China is a vast and populous country, moving rapidly on all fronts to prepare itself for life in the twenty-first century. Heir to a resplendent ancient culture, modern China is following a unique developmental path that evolves from this long and rich cultural tradition. Our understanding of the transformations in China today must be predicated upon an appreciation of this precious cultural legacy.

The challenge for The Metropolitan Museum of Art is to represent this colossal culture by the coherent display of aesthetic masterpieces that recapture the great moments of China's past. Collections such as that at the Metropolitan have grown under generations of collectors, curators, and changing fashions.

The Erickson Collection contains works of outstanding quality that range through different media and across the whole span of ancient China, from the Neolithic to the T'ang period. Ernest Erickson, through his collection, has created a vital memorial that fills in gaps in the Museum's existing holdings. We are honored and privileged to help present this wonderful gift, commemorated by this catalogue.

"The Arts of Ancient China": The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 32, no. 2 (1973–1974). Hearn, Maxwell K. (1973–1974)

Arts of the Sung and Yüan. Hearn, Maxwell K., and Judith G. Smith (1996)

Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Eighth–Fourteenth Century. Fong, Wen C. (1992)

Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Eighth–Fourteenth Century. Fong, Wen C. (1992)

Beyond Representation surveys Chinese painting and calligraphy from the eighth to the fourteenth century, a period during which Chinese society and artistic expression underwent profound changes. A fourteenth-century Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) literati landscape painting presents a world that is totally different from that portrayed in the monumental landscape images of the early Sung dynasty (960–1279). To chronicle and explain the evolution from formal representation to self-expression is the purpose of this book. Wen C. Fong, one of the world's most eminent scholars of Chinese art, takes the reader through this evolution, drawing on the outstanding collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Focusing on 118 works, each illustrated in full color, the book significantly augments the standard canon of images used to describe the period, enhancing our sense of the richness and complexity of artistic expression during this six-hundred-year era.

Placing equal emphasis on stylistic analysis, social context, and cultural values. Professor Fong considers several issues in Chinese art history: style and its social functions, the changing fortunes of the artist, antiquity and synthesis as guiding principles, and the Chinese view of creativity and change. In this exploration he highlights three areas of artistic accomplishment: narrative painting, the depiction of landscape, and the calligraphy and calligraphic painting of the scholar officials. Moving from art to history he outlines the schism within the Confucian state during the later Sung and the Yuan dynasties between the ruling imperial ideology and the humanist philosophy of the scholar officials, with the consequent rise of literati painting as the true voice of the Chinese artistic sensibility. The branching off into official and private narrative is mirrored in religious painting: while professional craftsmen continued the practice of courtly techniques in the painting of icons, Taoist and Ch'an Buddhist painters adopted scholarly aesthetic principles to create new, highly individualistic images and styles. Unlike narrative representation, which had a long history of development prior to the Sung, landscape painting began to emerge as a preeminent art form in the tenth century, reaching its zenith during the Northern Sung (960–1177), a golden age of art and cultural development. From the second half of the eleventh century, painters turned increasingly from more objective naturalistic landscape to landscape imbued with human emotion, breaking away from officially sanctioned pictorial conventions to create more symbolic representations of single flowers, rocks, and trees.

By the time of the Yuan dynasty, following the Mongol conquest of 1279, objective representation in art had been replaced by imagery that drew on the artist's inner response to the world. At this time, the painter began to inscribe poems and incorporate calligraphy in his works, the meaning of the painted subject made complex by personal and symbolic associations enhanced by its expression in language. With the multiple relations between word, image, and calligraphy forming the basis of a new art, Chinese painting entered its richest and most diverse stage of development.

China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D. Watt, James C. Y., An Jiayao, Angela F. Howard, Boris I. Marshak, Su Bai, and Zhao Feng, with contributions by Prudence O. Harper, et al. (2004)

China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D. Watt, James C. Y., An Jiayao, Angela F. Howard, Boris I. Marshak, Su Bai, and Zhao Feng, with contributions by Prudence O. Harper, et al. (2004)

The Han (221 B.C.–A.D. 206) and Tang (618–907) dynasties mark the two great eras of early imperial China. From the fall of the Han at the turn of the third century to reunification under the Sui in the seventh, the country experienced devastation from war and social upheaval. It was also, however, a period of creativity and cultural change. The political fragmentation that occurred between the dynasties and the massive migration of nomadic peoples into China resulted in contact with every part of Asia and the introduction of foreign ideas, religious, and art forms and motifs. An important aspect of the cultural exchange that took place at the time was the spread of Buddhism in China. By the Tang dynasty, thousands of foreigners were traveling to the capital, Chang'an, which flourished as a great cosmopolitan center of world commerce and culture

The integration of foreign motifs and styles with the traditional arts of China is the focus of this catalogue and the landmark exhibition that it accompanies, "China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D.," held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition comprises some three hundred objects, most of them excavated in recent years and many never before seen outside China. Each work is discussed in terms of its aesthetic qualities and art-historical significance and in the context of the philosophical and religious ideas that are reflected in iconography and style.

In an introductory essay, James C. Y. Watt, Brooke Russell Astor Chairman, Department of Asian Art, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, discusses the art and history of the entire period. Essays by both Chinese and Western scholars explore important aspects of metalwork, glass, and textiles, as well as the development of Buddhist art in China.

A Chinese Garden Court [adapted from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 38, no. 3 (Winter, 1980–1981)]. Murck, Alfreda, and Wen Fong (1980)

Cultivated Landscapes: Chinese Paintings from the Collection of Marie-Hélène and Guy Weill. Hearn, Maxwell K. (2002)

This catalogue presents twelve superb works by leading fifteenth- and sixteenth-century artists of the Wu school, centered in the cosmopolitan city of Suzhou, by early Qing loyalist, Orthodox school, and individualist painters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and by two twentieth-century masters. Richly illustrated and fully documented, each work is analyzed to elucidate its significance within its time, place, and the artist's oeuvre.

Cultural Convergence in the Northern Qi Period: A Flamboyant Chinese Ceramic Container, a research monograph. Valenstein, Suzanne G. (2007)

Defining Yongle: Imperial Art in Early Fifteenth-Century China. Watt, James C. Y., and Denise Patry Leidy (2005)

Defining Yongle: Imperial Art in Early Fifteenth-Century China. Watt, James C. Y., and Denise Patry Leidy (2005)

The imperial workshops of Yongle (r. 1403–24), third emperor of the Ming dynasty, produced superb paintings, sculptures, porcelains, and other luxury objects that became the foundation for subsequent developments in the arts for the remainder of the Ming dynasty. This volume traces the roots of the Yongle artistic styles to the previous dynasty, the Yuan (1271–1368), when China was ruled by the Mongols. It offers new insight into the emperor's attachment to Tibetan Buddhism, which is reflected in many of the objects illustrated in this volume. The Yongle reign was also a period of active trade and diplomatic exchanges between China and Central Asia and the Middle East, the influence of which can be seen in the decorative arts of this era: porcelain articles, for instance, copied the shapes of Islamic glass and metalware vessels. It was this masterful blending of indigenous Chinese themes with foreign styles and designs that created the vibrant synthesis of the arts that is a hallmark of the Yongle reign. This brief account of the arts is narrated against the life and times of one of the most powerful and complex personalities history has ever known.

East Asian Lacquer: The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection. Watt, James C. Y., and Barbara Brennan Ford (1991)

East Asian Lacquer: The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection. Watt, James C. Y., and Barbara Brennan Ford (1991)

Lacquer has long been one of the most intriguing arts of East Asia but is surprisingly little understood in this country. Fortunately, the American collectors Florence and Herbert Irving have lovingly assembled a distinguished collection of East Asian lacquer that is particularly strong in examples from the medieval period and in important but relatively unfamiliar types of lacquer. More than 180 treasures from that collection make up a remarkable exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and are presented in this book.

The luxury associated with lacquerware is legendary. Derived from the sap of a tree, lacquer is used to protect and decorate platters, boxes, and a wide range of other objects, many of them made for personal use. The methods employed vary enormously in technique and visual effect but have in common the lavish expenditure they require of time, labor, and artistry. In one type of Chinese lacquer, objects were coated with hundreds of applications of lacquer to build up a thick layer into which complex, rhythmic images were carved. Other types of lacquerware carry engaging scenes filled with figures and animals executed in intricate mother-of-pearl inlay. Japanese lacquerers developed an array of techniques for producing makie, a brilliant gold and silver decoration often used to illustrate seasonal themes or poignant passages from literature. Also from Japan, but entirely different, are austere, undecorated Negoro lacquers, prized for the color modulations worn into their surfaces by the passage of time. Other striking effects have been achieved through decorative techniques that include designs engraved and filled with gold, lacquer modeled in relief, the use of basketry, and inlays of metal, stone, or tortoiseshell. Astonishing in their inventiveness and virtuosity, all of these lacquer works provide rich visual rewards as well as aesthetic insights into the cultures that produced them.

The outstanding lacquers in this selection from the Irving Collection represent a wide range of styles and techniques. They date from the thirteenth to the twentieth century and originate in all four of the major East Asian areas of lacquer production: China, Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. The essays presented here draw on new scholarship to trace the history of lacquer's development within each of these cultures, explore stylistic relationships, and explain techniques of the art. Each catalogued object is discussed in detail and illustrated in color. Thus, the volume is at once an introduction to the lacquer of East Asia, a comprehensive scholarly treatment of it, and an immersion in its intense pleasures.

The authors of this book are James C. Y. Watt, Brooke Russell Astor Senior Curator of Asian Art, and Barbara Brennan Ford, Associate Curator of Asian Art, both at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. An essay on Japanese lacquer of the Momoyama period was contributed by Haino Akio, Curator at the Kyoto National Museum.

Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute: The Story of Lady Wen-chi. A Fourteenth-Century Handscroll in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rorex, Robert A., and Wen Fong (1974)

The Great Bronze Age of China: An Exhibition from The People's Republic of China. Fong, Wen, ed., Robert W. Bagley, Jenny F. So, and Maxwell K. Hearn (1980)

The Great Bronze Age of China: An Exhibition from The People's Republic of China. Fong, Wen, ed., Robert W. Bagley, Jenny F. So, and Maxwell K. Hearn (1980)

Nearly 4,000 years ago, the ancient Chinese made a discovery that would determine the course of their history and culture for two millennia—the alloy of tin and copper known as bronze. Bronze was used for tools and weapons and even musical instruments, but the Great Bronze Age of China has come down to us mainly in the ritual vessels that symbolized power and prestige for China's first three dynasties: the Xia, the Shang, and the Zhou. Passed on to successive conquerors, used to honor the ancestors, and buried—along with other grave goods and sacrificial victims or in storage pits by fleeing members of defeated dynasties—these exquisite bronzes reveal more about the character of life in ancient China than any other artifacts. As Chinese legend tells us, whoever held the bronze vessels held the power.

Recent archaeological excavations and recent diplomatic ties between the People's Republic and the United States have combined to make possible a unique exhibition of Bronze Age artifacts. Eighty-five bronzes—including vessels that range from the simplest wine cup to huge cauldrons, elaborate bird- and elephant-shaped containers, bells, and a standard top—are seen together for the first time on a generous loan from the People's Republic to five United States museums. Included are some objects so treasured that it was at first thought that they would not be permitted to leave China. Perhaps the most stunning objects are those from one of the most remarkable finds in the history of archaeology: in 1974, more than 7,000 life-size figures—a veritable army of warriors, cavalry, and chariots complete with horses and drivers—were discovered still standing, rank after rank, guarding the burial mound of China's first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi, who died in 210 B.C. Eight of them, six men and two horses, are included here, the first to be placed on exhibit outside China. Richly carved jades and an iron belt hook make up the remainder of the 105 objects presented. To document this extraordinary exhibition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, sent a special advance team of researchers and a photographer to China in 1979, led by director Philippe de Montebello. Represented in this catalogue are the results of that journey—color-plate illustrations of all of the objects in the show, including many details, supplemented by black and white photographs—most of them supplied by China's Cultural Relics Bureau—along with many drawings, charts, and maps.

A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics. Valenstein, Suzanne G. (1989)

A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics. Valenstein, Suzanne G. (1989)

This handsome book is at once a general survey of Chinese ceramics from the early Neolithic period to the present day and an essential reference volume for art historians and connoisseurs. Originally published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1975 as an introduction to its vast collection of Chinese ceramics, the book was highly praised by experts in the field. Over the last decade, however, thanks to accelerated archaeological activity in The People's Republic of China and important archaeological discoveries made elsewhere, substantial changes have been made in Chinese ceramic chronology and attributions. At the same time, analytic studies of Chinese ceramic technology have altered many basic concepts. This edition, written in the light of such enhanced knowledge, presents a far more detailed and comprehensive picture than could have been possible only a few years ago. A wealth of new information has been reported and integrated into the book, which begins over one thousand years earlier than the first edition. Almost half of the 335 objects illustrated are new to this edition; a 32-page section of color plates adds immeasurably to the usefulness of the book. This edition uses the Pinyin system of Chinese romanization; there is an appendix giving Pinyin/Wade-Giles equivalents, with the Chinese characters, as well as a chronology, maps, a glossary, selected readings, and an index. Invaluable for scholars will be the new technical information, references to relevant Chinese archaeological journals, and an appendix giving selective archaeological and other documentary comparisons to objects in the Museum's collection that are illustrated in the book.

"Highlights of Chinese Ceramics": The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 33, no. 3 (Fall, 1975). Valenstein, Suzanne G. (1975)

How to Read Chinese Paintings. Hearn, Maxwell K. (2008)

How to Read Chinese Paintings. Hearn, Maxwell K. (2008)

The Chinese way of appreciating a painting is often expressed by the words du hua, "to read a painting." How does one do that? Because art is a visual language, words alone cannot adequately convey its expressive dimension. How to Read Chinese Paintings seeks to visually analyze thirty-six paintings and calligraphies from the encyclopedic collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in order to elucidate what makes each a masterpiece.

Maxwell K. Hearn's elegantly erudite yet readable text discusses each work in depth, considering multiple layers of meaning. Style, technique, symbolism, past traditions, historical events, and the artist's personal circumstances all come into play. Spanning more than a thousand years, from the eighth through the seventeenth century, the subjects represented are particularly wide-ranging: landscapes, flowers, birds, figures, religious subjects, and calligraphies. All illuminate the main goal of every Chinese artist: to capture not only the outer appearance of a subject but also its inner essence. Numerous large color details, accompanied by informative captions, allow the reader to delve further into the most significant aspects of each work.

Together the text and illustrations gradually reveal many of the major themes and characteristics of Chinese painting. To "read" these works is to enter a dialogue with the past. Slowly perusing a scroll or album, one shares an intimate experience that has been repeated over the centuries. And it is through such readings that meaning is gradually revealed.

Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Painting. Smith, Judith G., and Wen C. Fong, eds., with contributions by Richard M. Barnhart, James Cahill, Wen C. Fong, Robert E. Harrist, Jr., Maxwell K. Hearn, Hironobu Kohara, Sherman Lee, Stephen Little, Qi Gong, Shih Shou-chien, Jerome Silbergeld, and Wan-go Weng (1999)

Landscapes Clear and Radiant: The Art of Wang Hui (1632–1717). Hearn, Maxwell K., ed., with Wen C. Fong, Chin-Sung Chang, and Maxwell K. Hearn (2008)

Landscapes Clear and Radiant: The Art of Wang Hui (1632–1717). Hearn, Maxwell K., ed., with Wen C. Fong, Chin-Sung Chang, and Maxwell K. Hearn (2008)Wang Hui, the most celebrated painter of late seventeenth-century China, played a key role both in reinvigorating past traditions of landscape painting and in establishing the stylistic foundations for the imperially sponsored art of the Qing court. Drawing upon his protean talent and immense ambition, Wang developed an all-embracing synthesis of historical landscape styles that constituted one of the greatest artistic innovations of late imperial China.

This comprehensive study of the painter, the first published in English, features three essays that together consider his life and career, his artistic achievements, and his masterwork—the series of twelve monumental scrolls depicting the Kangxi emperor's Southern Inspection Tour of 1689. The first essay, by Wen C. Fong, closely examines Wang Hui's genius for "repossessing the past," his ability to engage in an inventive dialogue with previous masters and to absorb their stylistic personae while making works that were distinctly his own. Chin-Sung Chang next traces the entire trajectory of Wang's development as an artist, from his precocious youth in the village of Yushan, through growing local and national fame—first as a copyist, then as the creator of groundbreaking panoramic landscapes—to the ultimate confirmation of his stature with the commission to direct the Southern Inspection Tour project. Focusing on this extraordinary eight-year-long effort, Maxwell K. Hearn's essay discusses the contemporary sources for the scrolls, the working methods of Wang and his assistants (comparing drafts with finished versions), and the artistic innovations reflected in these imposing works, the extant examples of which measure more than two feet high and from forty-six to eighty-six feet long.

Presented in this volume are twenty-seven of Wang Hui's major paintings, including two of the Southern Inspection Tour scrolls, drawn from The Metropolitan Museum of Art and from museums in Beijing, Taipei, Shanghai, the United States, and Canada. These are supplemented by a wealth of comparative images that range from ancient Chinese paintings and seventeenth-century woodblock maps to works by present-day artists. Invaluable information is provided by a scholarly catalogue, compiled by Shi-yee Liu, Research Associate in the Department of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum, which details the inscriptions, colophons, signatures, and seals of each work.

http://www.metmuseum.org/research/metpublications/Landscapes_Clear_and_Radiant_The_Art_of_Wang_Hui_1632_1717?Tag=&title=&author=&pt=0&tc=0&dept={AE42EDFF-A41C-42CC-B320-6B43C692336C}&fmt=0 Li Kung-lin's Classic of Filial Piety. Barnhart, Richard M., with essays by Robert E. Harrist Jr. and Hui-liang J. Chu (1993)

Li Kung-lin's Classic of Filial Piety. Barnhart, Richard M., with essays by Robert E. Harrist Jr. and Hui-liang J. Chu (1993)The figure painter Li Kung-lin, who lived in China from about 1041 to 1106, was the leading exponent of the Northern Sung scholar-official aesthetic. One hundred seven of his works were recorded in the great government catalogue of the imperial collection of paintings a few years after his death. Sadly, today only three of his works still exist. The handscroll of the Hsiao-ching, or Classic of Filial Piety, a classic of the orthodox canon of Confucianism, is one of those three. It is among the preeminent monuments of Chinese cultural and art history.

A slight volume composed of eighteen chapters, the Classic of Filial Piety takes the form of a dialogue between Confucius and his disciple Tseng-tzu on the meaning and application of filial piety in the affairs of the individual and of the state. The text dates to the period between 350 and 200 B.C., long after either Confucius or his immediate disciples lived, but its subject, the governing of relationships among men and the rules of conduct by which society is made secure, was for centuries before and for centuries to come the keystone of Chinese society.

Before Li's time, the art of painting had been a public and imperial art, conveying the images, ideas, values, and propaganda of the imperial court, the powerful hereditary families, and the great temples. In the eleventh century, under the inspiration of Li Kung-lin and a few others, painting was transformed into a formal mode of expression, which, like poetry, could serve to convey the mind of the artist as well as the emblems of those who controlled his life. For Li, art was a tool, a moral vehicle that allowed him to set out his views of the institutions, ideas, and conflicts of his time.

Richard M. Barnhart, Professor of the History of Art at Yale University, in his beautifully written text, guides the reader through the symbolic world of Li Kung-lin, elucidating the significance of the Classic of Filial Piety in the context of Chinese art and cultural history, providing an exegesis of each of the eighteen chapters and revealing the artist's beliefs, his thoughts and emotions. Professor Barnhart's contribution is augmented by a biography of the artist by Robert E. Harrist, Jr., Associate Professor of Art and East Asian Studies at Oberlin College; an analysis of Li Kung-lin's calligraphy by Hui-liang J. Chu, Assistant Curator of Painting and Calligraphy at the National Palace Museum, Taipei; and a detailed account of the handscroll's conservation and mounting by Sondra Castile and Tekemitsu Oba, both of the Department of Asian Art Conservation at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Manchu Dragon: Costumes of the Ch'ing Dynasty, 1644–1912. Mailey, Jean (1980)

Peach Blossom Spring: Gardens and Flowers in Chinese Painting. Barnhart, Richard M. (1983)

Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Fong, Wen C., and James C. Y. Watt, with contributions by Chang Lin-sheng, James Cahill, Wai-kam Ho, Maxwell K. Hearn, and Richard M. Barnhart (1996)

Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Fong, Wen C., and James C. Y. Watt, with contributions by Chang Lin-sheng, James Cahill, Wai-kam Ho, Maxwell K. Hearn, and Richard M. Barnhart (1996)Only two major exhibitions from the fabled Chinese Palace Museum collections have been seen in the West—the first in London in 1935–36 and the second in the United States in 1961–62. These two exhibitions provided an extraordinary stimulus to the study of Chinese culture, revolutionized Asian art studies in the West, and opened the eyes of the public to the artistic traditions of Chinese civilization. Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei is the publication that accompanies the third great exhibition of Chinese masterworks to travel to the West. Written by scholars of both Chinese and Western cultural backgrounds and conceived as a cultural history, the book tells the story of Chinese art from its foundations in the Bronze Age and the first empires through the rich diversity of art produced during the Sung, Yuan, Ming, and Ch'ing dynasties, contrasting China's absolutist political structure with the humanism of its artistic and moral philosophy. Synthesizing scholarship of the past three decades, the authors present not only the historical and cultural significance of individual works of art and analyses of their aesthetic content, but a reevaluation of the cultural dynamics of Chinese history, reflecting a fundamental shift in the study of Chinese art from a focus on documentation and connoisseurship to an emphasis on the cultural significance of the visual arts.

National treasures passed down from dynasty to dynasty, the works of art that now form the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, originally constituted the personal collection of the Ch'ien-lung emperor, who ruled China from 1736 to 1795. Two centuries after Ch'ien-lung ascended the dragon throne, when the Japanese invaded China in 1937, the nearly 10,000 masterworks of painting and calligraphy and more than 600,000 objects and rare books and documents—which had earlier been moved from Peking to Nanking following the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931—were packed in crates and evacuated to caves near the wartime capital, Chungking. It was not until after World War II that the crated treasures were moved to their present home in Taiwan, where today they represent a major portion of China's artistic and cultural legacy.

Drawing on this extraordinary collection, the authors explore in depth four interrelated themes: a cyclical view of history, the Confucian discourse on art, the social function of art, and possessing the past. The last theme, from which the volume takes its title, refers both to imperial China's possession of its past through the art of collecting and to the broader cultural tradition of embracing change through the creative reinterpretation of the past.

This major scholarly publication will expand our understanding and deepen our appreciation of works of art that over the centuries have emerged from a remarkable and, in the West, still largely unexplored culture.

Spirit and Ritual: The Morse Collection of Ancient Chinese Art. Bower, Virginia, and Robert L. Thorp (1982)

Splendors of Imperial China: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Hearn, Maxwell K. (1996)

Splendors of Imperial China: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Hearn, Maxwell K. (1996)

The collection of the National Palace Museum is made up largely of the personal holdings of the Ch'ien-lung emperor (reigned 1736–95). Representing the artistic legacy of imperial China, it offers an unsurpassed view of Chinese civilization. The objects lavishly illustrated and described in this book, which include magnificent ritual bronzes, precious jades, monumental landscape paintings, and exquisite ceramics, are among the finest ever created.

Published to accompany the exhibition "Splendors of Imperial China: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei," the book takes the reader through the most significant periods of Chinese culture: its foundations in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, its flowering in the sophisticated world of the Sung dynasty, its exuberance during the Ming, and its technical brilliance under the Manchus. The author makes the unique beauty of this art accessible through comparisons of selected works and through discussion of their historical context.

Summer Mountains: The Timeless Landscape. Fong, Wen (1975)

Summer Mountains: The Timeless Landscape. Fong, Wen (1975)

Landscape has been the dominant subject in Chinese painting ever since it emerged as the pre-eminent art form of the Northern Sung period (960–1127). The recent acquisition by the Metropolitan Museum, as a gift of the Dillon Fund, of a superb large Northern Sung handscroll, Summer Mountains, provides the opportunity to consider in some detail the landscape art of this period, together with its antecedents and later permutations.

Developing during the war-filled years of the tenth century, Northern Sung landscape painting produced timeless images that were followed and imitated for centuries. This art reached its apogee in the third quarter of the eleventh century. After the fall of the Northern Sung, it continued to be popular in the north, both under the Chin tartar and then the Mongol rule during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Meantime the painters of the Southern Sung (1127–1276), south of the Yangtze River, developed a simplified style that described the softer landscapes of the south.

There were three revivals of the Northern Sung grand manner in landscape painting, the first during the Yüan period (1277–1368), when the Mongols dominated the whole of China, the second in the fifteenth century, after the Ming overthrew the Mongols, the third at the turn of the eighteenth century, in the early Ch'ing (Manchu) period. Although landscape painting during the Yüan period and afterward was essentially different from that of the Northern Sung, it continued to evoke motifs and themes made popular by the Northern Sung masters.

Traditionally attributed to Yen Wen-kuei, a painter active about 980–1010, the Metropolitan Museum'sSummer Mountains is, instead, as work in Yen's style, probably painted about 1050. But since Yen's style remained influential for centuries, an analysis of the Yen Wen-kuei tradition becomes a capsule account of the development of Chinese landscape painting between 1000 and 1700.

As one attempts to date the many works in the Yen Wen-kuei tradition, it is necessary to keep in mind the following: When a painter works in the manner of an older master, he first adopts the characteristic brushwork idioms, the form elements, and the compositional motifs. But in expanding his interpretation and giving it new articulation, he necessarily deviates from the original and makes subtle changes. In short, the later painter shows in his work not the real earlier master but a transformed image of him. These changes are not "slips of hand" or "misunderstandings"; instead, they are positive signs of the later painter's own style. Even a more or less mechanical copy, which, in the absence of the original work may be historically useful in reconstructing it, inevitably reveals something of its own time.

Sung and Yuan Paintings. Fong, Wen, and Marilyn Fu (1973)

Treasures from the Bronze Age of China: An Exhibition from The People's Republic of China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1980)

When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles. Watt, James C. Y., and Anne E. Wardwell, with an essay by Morris Rossabi (1997)

When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles. Watt, James C. Y., and Anne E. Wardwell, with an essay by Morris Rossabi (1997)

When Silk Was Gold is the catalogue for the first exhibition devoted exclusively to luxury silks and embroideries produced in Central Asia and China from the eighth to the early fifteenth century. Drawn from the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art, the textiles are remarkable not only for their dazzling display of technical virtuosity but also for their historical significance, reflecting in their techniques and patterns shifts in the balance of power between Central Asia and China that occurred as dynasties rose and fell and empires expanded and dissolved.

The finest products of imperial embroidery and weaving workshops in the Middle Ages were among gifts presented by emperors and members of the imperial family to other rulers, emissaries, and distinguished persons. Richly woven textiles were also highly coveted as commercial goods. Transported across vast distances in unprecedented numbers to places as remote as the courts and church treasuries of Europe, they formed the mainstay of international commerce. Under the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), textiles were an important part of the Mongol patronage of Buddhist sects in Tibet, which was an important means of solidifying Mongol-Tibetan relations.

The material presented in this volume significantly extends what has been known to date of Asian textiles produced from the Tang (618–907) through the early Ming period (late 14th–early 15th century), and new documentation gives full recognition to the importance of luxury textiles in the history of Asian art. Costly silks and embroideries were the primary vehicle for the migration of motifs and styles from one part of Asia to another, particularly during the Tang and Mongol (1207–1368) periods. In addition, they provide material evidence of both the cultural and religious ties that linked ethnic groups and the impetus to artistic creativity that was inspired by exposure to foreign goods.

The demise of the Silk Roads and the end of expansionist policies, together with the rapid increase in maritime trade, brought to an end the vital economic and cultural interchange that had characterized the years preceding the death of the Ming-dynasty Yongle emperor in 1424. Overland, intrepid merchants no longer transported silks throughout Eurasia and weavers no longer traveled to distant lands. But the products that survive from that wondrous time attest to a glorious era—when silk was resplendent as gold.

Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Leidy, Denise Patry, and Donna Strahan (2010)

Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Leidy, Denise Patry, and Donna Strahan (2010)

The Metropolitan Museum's collection of Chinese Buddhist and Daoist sculpture is the largest in the western world. In this lavish, comprehensive volume, archaeological discoveries and scientific testing and analysis serve as the basis for a reassessment of 120 works ranging in date from the fourth to the twentieth century, many of them previously unpublished and all of them newly and beautifully photographed. An introductory essay provides an indispensable overview of Buddhist practices and iconography—acquainting us with the panoply of past, present, and future Buddhas, bodhisattvas, monks and arhats, guardians and adepts, pilgrims and immortals—and explores the fascinating dialogue between Indian and Chinese culture that underlies the transmission of Buddhism into China.

In addition to detailed individual discussions of fifty masterpieces—a heterogeneous group including portable shrines carved in wood, elegant bronze icons, monumental stone representations, colorful glazed-ceramic figures, and more—the catalogue presents a ground-breaking survey of the methods used in crafting the sculptures. A second introductory essay and several technical appendices address the question of how early Chinese bronzes, as opposed to those from Gandhara and other westerly regions, were cast; the construction methods used for wood sculptures in China, notably different from those used in Japan; the complex layers of color and gilding on works in all media and their possible significance; and the role of consecratory deposits in wood and metal sculptures. A final appendix publishes the results of an intensive analysis of the wood material in the collection, classifying every sculpture by the genus of its wood and including a section of photomicrographs of each wood sample—an invaluable resource for researchers continuing to study works of this genre.

As illuminating for new enthusiasts of Chinese Buddhist art as for scholars and connoisseurs, Wisdom Embodied is a glorious tour of the Metropolitan's unparalleled collection, certain to ear its place as a classic in the field.

Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting. Murck, Alfreda, and Wen C. Fong, eds. (1991)

Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting. Murck, Alfreda, and Wen C. Fong, eds. (1991)

In May of 1985, an international symposium was held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in honor of John M. Crawford, Jr., whose gifts of Chinese calligraphy and painting have constituted a significant addition to the Museum's holdings. Over a three-day period, senior scholars from China, Japan, Taiwan, Europe, and the United States expressed a wide range of perspectives on an issue central to the history of Chinese visual aesthetics: the relationships between poetry, calligraphy, and painting. The practice of integrating the three art forms—known as san-chiieh, or the three perfections—in one work of art emerged during the Sung and Yuan dynasties largely in the context of literati culture, and it has stimulated lively critical discussion ever since.

This publication contains twenty-three essays based on the papers presented at the Crawford symposium. Grouped by subject matter in a roughly chronological order, these essays reflect research on topics spanning two millennia of Chinese history. The result is an interdisciplinary exploration of the complex set of relationships between words and images by art historians, literary historians, and scholars of calligraphy. Their findings provide us with a new level of understanding of this rich and complicated subject and suggest further directions for the study of Chinese art history. The essays are accompanied by 255 illustrations, some of which reproduce works rarely published. Chinese characters have been provided throughout the text for artists names, terms, titles of works of art and literature, and important historical figures, as well as for excerpts of selected poetry and prose. A chronology, also containing Chinese characters, and an extensive index contribute to making this book illuminating and invaluable to both the specialist and the layman.

The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty. Watt, James C. Y., with Maxwell K. Hearn, Denise Patry Leidy, Zhixin Jason Sun, John Guy, Joyce Denney, Birgitta Augustin, and Nancy S. Steinhardt (2010)

The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty. Watt, James C. Y., with Maxwell K. Hearn, Denise Patry Leidy, Zhixin Jason Sun, John Guy, Joyce Denney, Birgitta Augustin, and Nancy S. Steinhardt (2010)

In 1215, the year Khubilai Khan (1215–1294) was born, the Mongols made their first major incursion into North China, initiating a period of innovation in the arts that had its greatest flowering in the Yuan dynasty, founded by Khubilai in 1271 and lasting until 1568. The creativity unleashed during this period of approximately 150 years was instigated by the confluence of the many cultures and ethnic groups that were brought together in a unified empire in China, which for centuries past had been politically divided. Skilled craftsmen from all over Central and Western Asia were relocated to workshops in North China, where they worked alongside Chinese artists, exchanging ideas and styles. This interaction eventually resulted in the creation of new art forms that would provide models for the arts of China in all subsequent periods until the twentieth century.

The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty, which accompanies a groundbreaking exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, is an in-depth discussion of the art and culture produced during this time, tracing the origins of the new art forms and exploring daily life in Yuan China, in particular at the imperial court and in the capital cities of Xanadu (present-day Shangdu) and Dadu (Beijing), and the impact on the arts of Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity, Manichacism, Hinduism, and Islam. The works of art and the archaeological finds on which the ten essays included in this volume are based are drawn principally from museums in China, with additional loans from museums in Taiwan, Japan, Russia, Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. The exhibition and catalogue, conceived and organized by James C. Y. Watt, Brooke Russell Astor Chairman of the Department of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum, illuminate our understanding of both the arts and the material culture of this period, telling the story of the emergence of a new Chinese art in a way that it has never before been told.

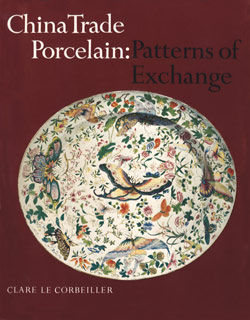

China Trade Porcelain: Patterns of Exchange. Le Corbeiller, Clare (1974)

China Trade Porcelain: Patterns of Exchange. Le Corbeiller, Clare (1974)

At the crest of the long commerce between China and the West in the mid- to late eighteenth century, Chinese porcelain was eagerly acquired by Western rulers, statesmen, leading families, and others alert for the novel. Its primary appeal was that it could be designed to order, and when it came off the trade ships a season or two later, many of the pieces—sometimes entire dinner sets—were decorated with family armorials, images still topical, or designs more or less freely reproduced from drawings or engravings sent to China the year before.

Recent interest in China trade porcelain has brought to light significant new examples of this ware. The present study deals with fifty-two pieces or groups of pieces added since 1955 to the Metropolitan Museum's well-known Helena Woolworth McCann Collection of China Trade Porcelain. Dating from the early sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, these tapersticks, cups, pitchers, plates, dishes, and tureens tell us a good deal about the growth of European interest in the ware, how Western tastes in design changed, how the makers' skills and techniques took them from blue-and-white ware through grisaille and famille rose painting to polychrome plus gilt, and how the shapes of porcelains reflected in some cases the direct influences of European metalwork and glassware.

All fifty-two additions to the collection are comprehensively illustrated—nearly a quarter of them are shown in color—and numerous views of comparable pieces in other collections are included, as well as the original pictorial sources for many of the painted decorations.

The author, Clare Le Corbeiller, is Associate Curator of Western European Arts in the Metropolitan Museum. Her work carries forward the account published by the Museum in 1956, China—Trade Porcelain, but it may be read as a wholly independent volume. As such, it offers documented new material for the collector of Chinese porcelains and a wide-ranging, charmingly informative introduction to the subject for anyone.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)