First selling exhibition of Buddhist art at Sotheby's in more than a decade announced

A Grey Schist Standing Bodhisattva, Ancient region of Gandhara, Kushan period, circa 3rd-4th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

NEW YORK, NY.- Coinciding with the auctions and events of Asia Week in September, Sotheby’s will present a selling exhibition, Footsteps of the Buddha: Masterworks from Across the Buddhist World, the first of its kind in more than a decade at Sotheby’s. Offering an extraordinary opportunity for collectors and connoisseurs, the selling exhibition traces the historical development and transformation of Buddhist art as it traveled throughout Asia from the 2nd century through the 21st century. This exhibition features pan-Asian Buddhist paintings and sculptures from the ancient regions of Gandhara, Nepal, Tibet, Korea, China and Japan. Organized jointly by Sotheby’s Asian art division, the exhibition aims to introduce important Buddhist artwork to a wider audience. The works will be on view in our New York galleries from 3 through 23 September.

“With the success of SHUIMO/Water Ink in March we are delighted to be hosting the Footsteps of the Buddha selling exhibition during our Asian Art auctions in September. These exhibitions in our state-of-the-art second floor galleries allow us to showcase an area of Asian Art in depth and have been enthusiastically received by collectors both here and around the world,” says Henry Howard-Sneyd, Vice Chairman, Asian Art.

Jacqueline Dennis, Specialist, Indian & Southeast Asian Art Department, notes, “This exhibition provides collectors and connoisseurs with a unique perspective on a variety of cultures through the prism of Buddhism. The 31 pieces in this exhibition display the distinct artistic heritages and aesthetics of their countries of origin, but at the same time, they share a common history and iconography. They express Buddhist philosophical concepts, show how Buddhism influenced the culture of the countries it penetrated, and how those countries made Buddhism their own. These timeless works of art also show how Buddhist art transformed through space and time, and continues to be a vital force in Asia today.”

A major highlight of the exhibition is an extraordinary grey schist standing Bodhisattva, a superlative example of Gandharan style of sculpture. The region of Gandhara, located at the center of the Silk Routes, was particularly influenced by Hellenistic culture resulting from the travels and military campaign of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. The legacy of Hellenism that he left was integrated into local traditions, out of which was born the Gandharan School of art, a unique mix of East and West. This monumental work of art from circa 3rd/4th century is from a particularly unique period of Asian and Buddhist history.

A Grey Schist Standing Bodhisattva, Height: 36 3/4 in. (93.4 cm), Ancient region of Gandhara, Kushan period, circa 3rd-4th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Agnelli Collectino, Turin, circa 1960s

NOTE: This well-proportioned and skillfully carved sculpture depicts a bodhisattva standing in elegant ease. His youthful face with downcast eyes and pursed lips bears a serene expression. His hair is arranged in an elaborate coiffure of curls and looped tresses terminating in a domed top knot above his head secured by a jeweled fillet, further adorned in a jeweled collar with matching armband and a looped chain necklace withmakara terminals centering a now-missing gem. His finely pleated robes offer a striking contrast to his bare muscular torso and typify the Gandharan style of drapery for which these sculptures are famous.

The bodhisattva, or enlightened being, was a central feature of Mahayana Buddhism which was popular in the Gandharan region during the early centuries of the Common Era. The Mahayana ideology advocated the importance of faith in the Buddha principle, expressed through love and devotion, as the most important element in the achievement of salvation. The means through which salvation could be attained was worship of the bodhisattva, who was also a model of benevolence and compassion, qualities exemplified in the present sculpture.

The bodhisattva’s rich accoutrements display the syncretic nature of jewelry traditions in vogue at the time. While the collar and matching armbands were staples in Indic representations of deities, the pendent necklace with figural terminals is completely Hellenistic in style and conception. The chains are in the loop-in-loop style which was widely prevalent in Greek jewelry. The makara terminals are obviously of Indic origin but it is interesting to note that the tradition of figural and animal-headed terminals was also a fixture of Scythian and Parthian ornamentation.

The present lot may be compared with two similar sculptures of youthfulbodhisattvas in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum (acc. 939.18.1 & 940.18.1) see I. Kurita, Gandharan Art II: The World of the Buddha, Tokyo, 2003, pl.15 & 16. The comparable works cited above have been identified as Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future, based on their flowing tresses, a reference to the deity’s ascetic antecedents in Mahayanist theology. The sculpture’s refinement and elegant restraint place it in 2nd/3rd centuries CE, often considered the ‘high’ period of Gandharan art.

A magnificent 12th century West Tibetan bronze figure of Bodhisattva Manjushri is an early work influenced by Kashmiri and western Himalayan sculpture. This rare, elegant and proportioned work of art is quite large for a bronze of this time period.

A copper alloy depicting Bodhisattva Manjushri. Height: 18 in. (46 cm), West Tibet, circa 12th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Vittorio Eskenazi, Milan, 1981

Litterature: Vittorio Eskenazi, Milan, 1981

Several stylistic concerns, such as the foliate motif of the body garland (as compared to the floral garland motif of 11th century West Tibetan bronzes); the treatment of the jewelry; the tubular shape of the torso; and the abbreviated petals of the lotus accoutrement at right suggest a later date of circa 12th century for this sculpture.

Compare the foliate body garland with a 12th century bodhisattva Avalokiteshavara now in the Norton Simon Museum, see P. Pal, Art from the Himalayas and China, New Haven and London, 2003, p. 137, pl. 89. See also U. von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, p. 133, pls. 23 E, F and G for three additional examples of foliate body garlands on 12th century standing Bodhisattvas.

Also compare an 11th century standing bronze bodhisattva in the Kashmiri style from Guge, see U. von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 85, fig. 11-13; as well as another 11th century standing bronze Padmapani in the Cleveland Museum, acc. no. 1976.70.

A further highlight of the selling exhibition is an Udayana Buddha from the Qianlong period (1735-1796) of China. This gilt copper alloy statue celebrates an ancient tradition associated with the introduction of Buddhism to China. This style of gilt bronze has become known in China as Udayana after legends surrounding an historical Indian ruler and a sandalwood statue brought to China in antiquity.

PROVENANCE: Acquired in Europe in the 1990s

Description: The specific iconographic formula of abhaya and varadamudra and stylized robe with concentric raised folds has been known in China from at least the early 5th century when Chinese sculptural style was influenced by the Buddhist art of India and Central Asian cultures. The style of the gilt bronze has become known in China as Udayana after legends surrounding an historical Indian ruler and a sandalwood statue brought to China in antiquity. Numerous and competing myths surround the now-lost sandalwood image. Records survive however of Chinese expeditions to India where Buddhism was dominant in the Kushan empire from the 1st century CE, and it is likely that Indian Buddhist sculptural traditions thus found their way to China.

Testimony to this migration of style is seen in two Northern Wei bronze Buddhas, one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among the largest and most important early gilt bronze Buddhist images from China and dated by inscription to the equivalent of 486 CE, and another in a private collection from 443 CE, see D. Leidy, Notes on a Buddha Maitreya sculpture dated 486 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Oriental Art 55, no. 3 (2005-6), p. 22, fig. 1 and p. 28, fig. 12. Both statues show the Buddha standing straight with hands in abhaya and varadamudra, robe falling in stylised concentric folds and wavy hair with whorls at the front.

The origin of the bronzes’ style can be traced to early Gandharan sculpture where Classical Greco-Roman conventions influenced the Buddhist art of the region, with later stylisation of the robe in 3rd and 4th century Mathura sculpture that almost perfectly reflects the concentric folds of the Wei Buddhas’ robes and sinuate fall of cloth from the arms, see S. Czuma, Kushan Sculpture: Images from Early India, Cleveland, 1985, p. 72, cat. no. 16. The upright stance of the Northern Wei Buddhas, the hand gestures of abhaya and varadamudra, the folds of the robe and the wavy hair with whorls at the front are the stylistic source of a myriad Ming and Qing dynasty versions such as the present example, where the whorls of hair of the original are interpreted as discs. The later renditions in the Udayana style pay homage to the origins of Chinese Buddhism in the recreation of the Indo-Chinese styles with which early Chinese Buddhist sculpture is associated. The Udayana mythology did not prevail in Tibet and the genre is exclusive to Chinese Buddhist sculpture.

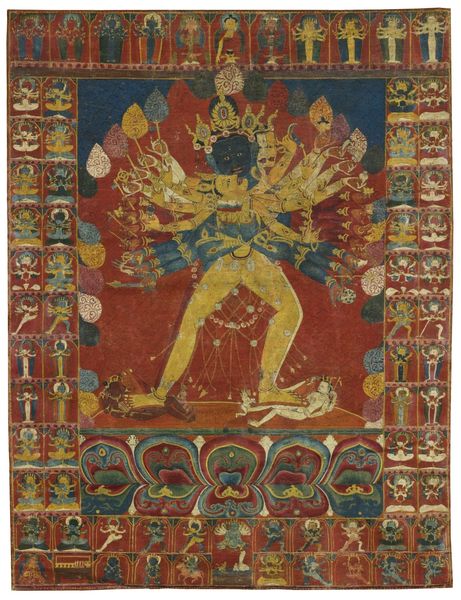

An important painting of the Kalachakra mandala, an early 15th century work, depicts the mandala, or cosmos, of the Buddha Kalachakra, Wheel of Time. The predominant reds and blues of the painting together with the symmetry of design and geometric placement of the deities suggest a Nepalese artistic style in the central regions of Tibet. This painting is one of the earliest representations of Kalachakra in Tibetan art.

A thangka depicting Kalachakra , 36 by 26 in. (86.4 by 66 cm), Tibet, early 15th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Private European collection, acquired 1970s/early 1980s

Litterature: M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred Circle in Tibetan Buddhism, London, 1997, p. 96, pl. 47

The painting depicts the mandala of the Buddha Kalachakra, Wheel of Time, with the multi-colored semi-wrathful god in union with his prajña Vishvamata, Mother of the Universe. The deities represent one of the most complex practices of the Unexcelled Yoga Tantras in Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism. Kalachakra is depicted with four heads and twenty-four arms, with his principal head and upper body in blue symbolising great wisdom. His red face represents passion, the white purity, and the yellow head facing rearwards, single-mindedness in meditation. One leg is white and the other red, denoting two separate halves of the yearly cycle.

Description: In union with his golden eight-armed prajña with four heads in white, blue, red and gold, the couple represent the embodiment of wisdom and compassion, the goal of Tibetan meditational practise leading to enlightenment and salvation of sentient beings: for an exhaustive treatise on the Kalachakra Tantra see M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred Circle in Tibetan Buddhism, Serindia Publications, London, 1997.

The predominant reds and blues of the painting together with the symmetry of design and geometric placement of the deities suggest a Nepalese artistic style in the central regions of Tibet in the early fifteenth century. The rectangular central space reserved for the principal deity is seen in 14th and 15th century Tibetan paintings in the Nepalese style such as a Raktayamari in the Kronos Collections, a Chakrasmavara mandala in a private collection and a Mahavajrabhairava mandala in the Pritzker Collection, see S. Kossak and J. Singer, Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet, New York, 1999, cat. nos. 40, 43, 44. The crown type of the subsidiary deities is comparable to that of a Guhyasamaja illumination in an early 15th century Tibetan manuscript in the Nepalese style, possibly painted at the Sakya monastery of Shalu, see P. Pal, Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection, Los Angeles, 1983, pp. 128-9, M4b.

The painting is one of the earliest representations of Kalachakra in Tibetan art, together with a 14th or 15th century mandala now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, see D. Leidy and R. Thurman, Mandala: the Architecture of Enlightenment,New York & Boston, 1997, p. 100, cat. no. 29, and the renowned 14th century gilt bronze Kalachakra and Vishvamata kept at Shalu monastery, see U. von Schroeder,Buddhist Bronzes in Tibet, Hong Kong, 2001, Vol. II, p. 965, pl. 232C.

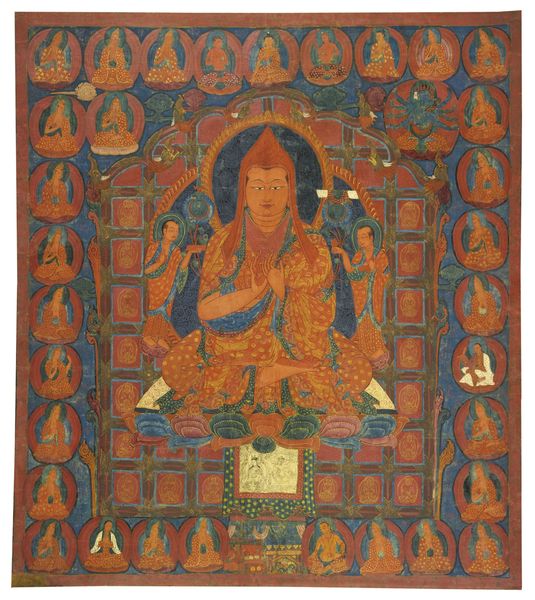

Also included in the selling exhibition is a rare 15th century thangka depicting Tsongkhapa from Guge in West Tibet, rarely seen on the market.

A thangka depicting Tsongkhapa with two kadam lineages, 36 by 31 in. (91.4 by 78.7 cm), West Tibet, 15th century. Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: The Koelz Collection, acquired in West Tibet by American biologist Dr. Walter N. Koelz of the Himalayan Research Institute of the Roerich Museum, 1930-33

Christie's New York, October 3, 1990, lot 107

Description: The current work depicts the scholar and founder of the Geluk order of Tibetan Buddhism, Tsongkhapa Losang Drakpa (1357–1419) flanked by his two main disciples, Gyaltsab Dharma Rinchen and Khedrub Gelek Pelzang. A spiritual and intellectual revolutionary, Tsongkhapa is renowned as the author of such seminal texts as theLamrim chenmo (The Great Stages of the Lamrim Path) and the sNgagsrim chenmo (The Great Presentation of the Stages of Tantra); as well as his complete revision of the understanding the Prasangika-Madhyamaka, still today the fundamental philosophical tenet system of the Geluk order.

In the immediate years following his death in 1419, many of Tsongkhapa’s patrons and disciples commissioned portraits of their late master. The current work is likely one such commission, created in West Tibet in the 15th century during the beginning of the Guge revival period, in which the local style with its powerful Kashmiri/Western Himalayan influence fused with Indo-Newari and Chinese stylistic elements popularized in Central Tibet.

In the current work, compare the long, elegant fingers and the narrow shape of the eyes of the three central figures, as well as the crenellated edges and red decoration of the lotus throne and the pictorial scene on the throne cloth to a late 15th century thangka depicting Shakyamuni Buddha from the Guge revival period, see M. Rhie and R. Thurman,Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet, San Francisco, 1991, 9. 87, cat. no. 6. Also compare a late 15th century wall painting of Prajñaparamita at Tholing in West Tibet for further examples of the elongated fingers, narrowed eyes, the crenellated edging of the lotus petals, and the red on white decoration of the lotus throne, seeibid., p. 57, fig 23. See also P. Pal, Art of Tibet, Los Angeles, 1990, p. 77, pl. 13 (P8) for an example of a similar cartouche depicting a donor and his ritual offerings; a panel depicting two deities beneath the lotus throne; the crenellated edging of the lotus petals; the arrangement of figures surrounding the central deity as well as the arrangement of lineage figures along the outer edges of the thangka. The unusual cartouche element below the lotus throne depicts the goddess Tara, the cult of whom was introduced to Tibet by Atisha, as well as a wrathful protector deity, possibly Shadbhuja Mahakala.

Although in the present work the individuals in the outer borders are not identified, we can infer from the composition that these represent the two Indo-Tibetan lineages of Yogachara and Madhyamaka, the legacy of the Kadampa tradition first propagated by Atisha, and later, by Tsongkhapa. These two lineages begin at the upper register: the Yogachara lineage descends anticlockwise from Shakyamuni Buddha at upper center; the Madhyamaka lineage descends clockwise from the same central point. For further discussion and similar compositions of Tsongkhapa with Kadam lineages, see two contemporaneous 15th century Tibetan paintings in the Rubin Museum of Art, acc. nos. F1997.31.14 and F1996.5.1.

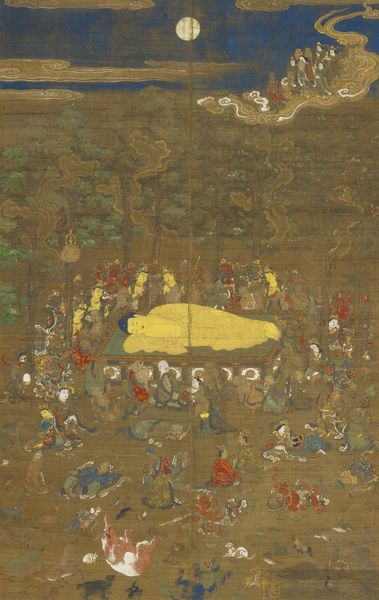

A further highlight is The Parinirvana of Buddha, a painting from the 16th/17th century in Japan, which depicts parinirvana (the ultimate nirvana), which occurs with the death of the physical body of the enlightened Buddha. The commemoration of this occasion is one of the most important events in the Buddhist calendar, and paintings such as this appeared as the focus of these ceremonies during the Nara period (710 – 794). There are several examples of such paintings in temples and museums including an 11th century National Treasure housed in Kongobuji in Koyasan and a 12th century example in the Tokyo National Museum.

A painting depicting The Parinirvana of Buddha, Japan, 16th-17th century, ink and color on silk, mounted in brocade as a hanging scroll, 44 ¾ by 28 ½ in (43 by 72.3 cm.). Photo: Sotheby's.

PROVENANCE: Private Japanese Collection, 1970s

Description: The commemoration of Buddha's parinirvana is one of the most important events in the Buddhist calendar, marking the final of the eight major events in his life. Commemorated with special ceremonies on the 15th day of the second month, large painted images of the Buddha entering the 'ultimate' nirvana, death of the physical body and freedom from the cycle of birth and rebirth, appeared as the focus of such ceremonies from the Nara period (710-794) onwards. The present painting follows the standard stylistic and iconographic conventions of earlier paintings as can be seen from the earliest surviving examples dating to the Heian period.

In the present example, Buddha lies peacefully on a raised platform beneath flowering sala trees, surrounded by a large grieving crowd. Some like the animals and oni are so overcome with grief that they roll around on the ground, their attachment to Buddha's physical body revealing their imperfect wisdom. Even Ananda lies passed out from grief, while the older, wiser Kasyapa tries to revive him. The enlightenedbodhisattvas on the other hand, depicted with golden bodies, stand serenely by, understanding that all beings eventually die, and that the ultimate goal is release fromsamsara, the bitter realm of existence. Ksitigargha bodhisattva, however, known in Japanese as Jizo, is depicted as a monk, kneeling calmly by Buddha's side. In the upper right Buddha's mother Mahamaya hastens down from heaven accompanied by an entourage.

As mentioned, paranirvana is the ultimate nirvana which occurs with the death of the physical body of someone who has attained enlightenment. It implies a release from all suffering, an end to future rebirths and the dissolution of the aggregates that make up existence. Shakyamuni Buddha’s parinirvana has been depicted in sculpture and paintings since very early on in India. The purpose of such depictions is to help devotees put things into perspective by reminding them that all beings die, and that nothing is permanent. Everything is subject to decay and final reunification with the cosmos.

There are many extant examples of such paintings in temples and museums. The oldest known piece dating to the 11th century, is a national treasure housed in Kongobuji in Koyasan, while a 12th century example is in the Tokyo National Museum. There are 14th century examples in the Museum fur Ostasiatische Kunst, Koln and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, illustrated in Zaigai Nihon no shino, I Bukkyo kaiga, Tokyo, 1980, nos. 8-10. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has four such paintings, including a woodblock print on the subject.

Ambivalent Resolution, by Gonkar Gyatso, one of the most significant contemporary artists from Tibet today, features a seated Buddha and is a superb example of the artist’s pioneering modernism, juxtaposing traditional Buddhist imagery and symbols of pop culture. The surface of the sculpture is covered in the artist’s trademark stickers and rhinestones – a mixture of American, European, Tibetan and Chinese decals featuring images of newspaper headlines, manga characters and superheroes, corporate logos and excerpts from Tibetan texts, all engulfed in cartoon flames. Gyatso’s work is held in the permanent collections of the Rubin Museum in New York, and the Devi Art Foundation in Gurgaon, India, and will be featured in an upcoming exhibition of Tibetan contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 2014.

Gonkar Gyatso (B.1961), Ambivalent Resolution. Executed in 2013. Stickers, paper collage, pencil, marker, polyurethane finish on resin sculpture. Height: 32 in. (81.3 cm). Photo: Sotheby's.

Description: One of the most important contemporary artists from Tibet working today, Gonkar Gyatso is renowned for his lyrical and ironic pop montaging in sculpture, printmaking, collage and painting. Executed in 2013, Ambivalent Resolution is a superb example of Gyatso’s pioneering modernism, negotiating the juxtaposition of traditional Buddhist imagery and poignant symbols of pop culture.

Gonkar Gyatso has appropriated the iconic Buddha figure as the seminal image of his oeuvre. Ambivalent Resolution features a seated Buddha figure, whose elegant limbs follow traditional 14th century Buddhist iconometrical standards of proportion. The sculpture is digitally scanned, digitally manipulated and then turned into a mould from which the resin sculpture is cast. Rather than the familiar, erect posture of meditation associated with imagery of the Buddha, Gyatso’s figure sits slouched, headless. The surface of the sculpture is covered in the artist’s trademark stickers—a mixture of American, European, Tibetan and Chinese decals featuring images of religious leaders, newspaper headlines, manga characters and superheroes, corporate logos and excerpts from Tibetan texts, all engulfed in cartoon flames. Gyatso’s hybrid aesthetic reveals a unique and deeply personal cross-fertilization of references, technique and experience as he seeks to reinvent the stereotypes concerning the visual culture of Tibetan Buddhism.

Born in Lhasa in 1961, Gonkar trained in traditional brush painting at the Central University for Nationalities in Beijing from 1980 to 1984 as well as traditional Tibetanthangka painting in Dharamsala; he later received his MA in Postmodern Art at the Chelsea College of Art and Design in London. In 2003, the artist founded the Sweet Tea House in London, dedicated to promoting contemporary Tibetan art and bringing together artists from inside Tibet and from abroad.

The artist’s mixed media works have been exhibited worldwide, and were featured in the Arsenale at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009 and the 17th Biennale of Sydney in 2010. Gyatso’s work is held in the permanent collections of the Rubin Museum in New York; the Newark Museum in New Jersey; the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford; and the Devi Art Foundation in Gurgaon, India, among others, and has been represented in major museum exhibitions including the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art; the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; the Tel Aviv Museum of Art; the Institute of Modern Art in Australia; and the Chinese National Art Gallery in Beijing. Gyatso’s work will also be featured in an upcoming exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 2014.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240309%2Fob_020705_110-1.jpeg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240309%2Fob_113c6e_79-1.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F70%2F68%2F119589%2F129847829_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F30%2F56%2F119589%2F129804783_o.jpg)