San Francisco's Asian Art Museum welcomes the world's first major exhibition exploring yoga

Three aspects of the Absolute, page 1 from a manuscript of the Nath Charit, 1823, by Bulaki. India. Opaque watercolor, gold, and tin alloy on paper. Courtesy of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, RJS 2399.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA.- The Asian Art Museum presents Yoga: The Art of Transformation, the first major art exhibition to explore yoga and its historical transformation over the past 2,500 years through more than 130 rare and compelling artworks.

All over the world, millions of people practice yoga to find spiritual insight and improved health. Many people are aware of yoga's origins in India, but few outside of advanced practitioner circles recognize yoga's profound philosophical underpinnings, its presence within Jain, Buddhist, Hindu and Sufi religious traditions, or the surprisingly various social roles played by yogic practitioners over centuries. This exhibition shows yoga’s rich diversity and rising appeal from its early days to its emergence on the global stage.

Borrowing from 25 museums and private collections in India, Europe and the U.S., the artworks on view date from the 2nd to the 20th centuries, with a majority from the 8th to 18th centuries. Throughout the exhibition, stunning examples of sculpture and painting illuminate yoga's key concepts as well as its obscured histories. Early photographs, books and films show yogis not only as peaceful practitioners, but also satirized as sly imposters. Artworks and audio guides also reveal yoga’s transformation in 20th-century India and the U.S. as an inclusive practice open to all. The exhibition’s highlights include an installation that reunites three stone yoginis from a 10th century South Indian temple; 10 pages from the first illustrated book of yogic postures (asanas) from around 1600; and a film by Thomas Edison, Hindoo Fakir (1902), the first American movie ever produced about India.

Curated originally for the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery by the associate curator of South and Southeast Asian Art, Debra Diamond, the Asian Art Museum’s presentation is organized by the museum’s associate curator of South Asian Art, Qamar Adamjee, and assistant curator of Himalayan Art, Jeff Durham.

“We are honored to serve as the only West Coast venue in presenting this historic exhibition, one of the most remarkable surveys of Indian art,” said Asian Art Museum director Jay Xu. “We hope that by illuminating aspects of yoga and its hidden histories to Bay Area audiences, visitors can take new perspectives to their present and future yoga practices.”

The exhibition surveys the centrality of yoga in Indian culture and focuses on core elements of yoga practice; the role of teachers; the importance of place in yoga practice; the associations between yoga and power; ways in which yogis have been understood and imagined in Indian and Western popular cultures; and the transformation of yoga into today’s contemporary practice. Visitors are encouraged to start their journey in Osher Gallery, followed by Hambrecht Gallery and then Lee Gallery.

Osher Gallery: The Path of Yoga

The exhibition begins by introducing visitors to yoga’s origins. Between 500 and 200 BCE, wandering ascetics of the Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain religions developed practices for controlling the body and breath as a means of stilling the mind. These practices introduced concepts that laid the groundwork for much of what later came to constitute yoga. By the 7th century, many of yoga’s key concepts, vocabulary and practices were established.

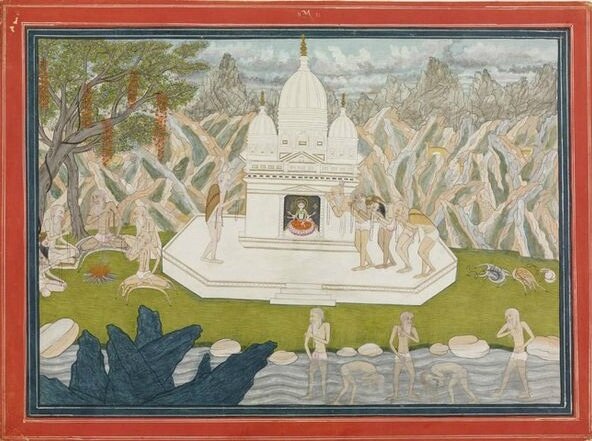

This gallery reveals how artists translated yogic identities, beliefs and practices into meaningful, eloquent visual forms. In yoga, the body is both what must be transcended as well as the necessary tool for attaining enlightenment. This is portrayed in the 19th century painting Three aspects of the Absolute, page 1 from a manuscript of the Nath Charit (cat. no. 4a), where the artist used shimmering gold pigment to depict the origins of existence as a shimmering field of gold and its successive emanations—into consciousness (center) and form (right) — are represented as a perfected yogi.

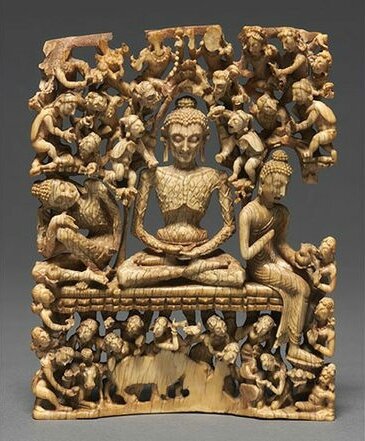

Because yoga, at its core, is a practice rooted in the mind and body, artworks in this gallery illuminate elements of yoga practice, including meditation, postures (asanas) and austerities — rejections of material attachment. Classic forms of austerities are fasting, celibacy and immobilizing the body in difficult positions. Examples of these artworks include the ivory sculpture Fasting Buddha (cat. no. 6b) and the striking bronze sculpture of Narasimha (cat no. 8a), the man-lion incarnation of the Hindu deity Vishnu, meditating with a yoga strap.

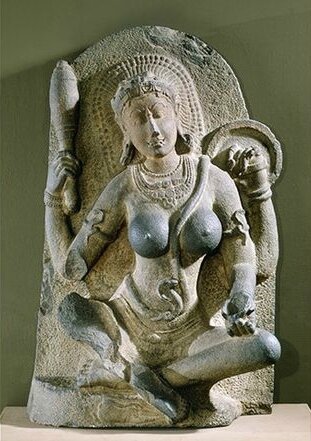

The gallery also presents early developments in conceptions of the yogic body. The chakras of the subtle body, page 4 from a manuscript of the Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati (cat. no. 11b) is a colorful 19th-century painting that maps out the energy centers of the body (chakras). Vishnu is depicted in a small but powerful painting, Vishnu Vishvarupa (cat. no. 10b), in his infinite cosmic form. Three yogini sculptures( cat. no. 3a-c), rare stone works from the 10th and 11th centuries from a South Indian temple, are displayed, each designed to have four arms to signify their divine status.

Hambrecht Gallery: Yogis in the Indian Imaginatio and the Western Imagination

Hambrecht Gallery primarily explores the theme of yoga in the Indian and Western imaginations, while also looking at the importance of place in yoga practice and the associations between yoga and power.

The paintings in this gallery show that not all yogis were peaceful; tales of wise and violent yogis instructed, amused and horrified many Indian listeners since at least as early as the Hindu epic Mahabharata (200BCE–400 CE). Continuously retold in folktales, poetic verses, sacred texts and literary narratives, these stories established both sage and sinister yogis firmly in the Indian imagination. The popular understanding and representation of female yoga practitioners (yogini) changed over time from region to region and within religious traditions. For example, a 17th century painting, Yogini with mynah (cat. no. 3f), depicts a yogini in a surreal landscape with surging hills and large flowers. This artwork was created at the Islamic court of the Indian city of Bijapur, where yoginis were considered agents of supernatural power capable of helping rulers win battles. Another group of paintings, illustrating modes of classical Indian music (ragas), visualize specific emotions evoked by each musical mode as yogis and yoginis, suggesting an experience that transcends the individual senses of seeing and hearing.

The gallery also depicts yogis in the Western imagination in the 17th through the 20th centuries. Images of yogis created for Western viewers spread rapidly, sensationalizing and dramatizing yoga culture. Photographs of near-naked yogis with long matted locks and mysterious body markings, engaging in spectacular rituals, flooded the market, like the Group of Yogis (cat. no. 21s), an image from the late 19th century. Additionally, Europeans were fascinated with documenting yogis in seemingly painful practices like lying on a “bed of nails” or posing in “fantastic” postures as seen in Bernard Picart’s print, Various Temples and Penances of the Fakirs (cat. no. 22a).

Film and photography continued to spread stereotypes of yogis to Western audiences. Thomas Edison’s film Hindoo Fakir (cat. no. 23d) featured an Indian magician’s stage act, helping to introduce so-called “Eastern mysticism” into the realm of cinema. By 1941, when The Yogi Who Lost His Willpower (cat. no.23e) was filmed, mainstream American culture knew the wonder-working yogi as a cultural motif.

Lee Gallery: Modern Transformations

This gallery focuses on the yoga renaissance of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tracing the basics of modern yoga—seen by many as a non-sectarian health practice and posture sequences. Modern yoga first took tangible form with the publication of Raja Yoga in 1896 by Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), whose teachings reformulated yoga as an empirical and scientific spiritual system inclusive of all. This gallery features photographs of Vivekananda (cat. no. 24) bringing these teaching to the U.S. in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Lee Gallery also looks at the rising popularity and the ascendance of yoga postures ( asanas), pointing out that there is scant evidence that postures were the principal feature of any pre-modern tradition of yoga. The rise of postural yoga emerged with Indian teachers in the early 20th century. Its prominence is inconceivable without visual culture to spread knowledge of the postures and sequences. Featured in Lee Gallery is a book containing one of the earliest illustrated compilations of yoga postures, Fakirs and their Practices in Ancient and Modern India (cat. no. 26a), as well as a video, T. Krishnamarchya Asanas (cat. no. 26i), which may be the earliest film of renowned yoga teacher T. Krishnamarchya (1888–1989) demonstrating posture sequences.

The exhibition concludes with the emergence of modern yoga—the regimens of health, fitness and spiritual well-being that are familiar today. An interactive historical timeline of yoga in California is also on display in the museum’s North Court.

Yogini, 900–975. India; Kanchipuram or Kaveripakkam, Tamil Nadu state. Possibly dolerite. Courtesy of Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, L.A. Young Fund, 57.88.

The five-faced Shiva, approx. 1730–1740. India. Watercolor on paper. Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Given by Col. T. G. Gayer-Anderson and Maj. R. G. Gayer-Anderson, Pasha, IS 239–1952.

Vishnu in his man-lion incarnation as Yoga-Narasimha, approx. 1250. India. Bronze. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Norman Zaworski, 1973.187.

Fasting Buddha, 700–800. India; Jammu and Kashmir state. Ivory. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund, 1986.70.

Headstand (Persian: akucchan), from a manuscript of Bahr al-hayat (Ocean of Life), 1600–1604. India. Opaque watercolor on paper. Courtesy of Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, In 16.20a.

Vishnu Vishvarupa, approx. 1800–1820, by Bulaki. India. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Given by Mrs. Gerald Clark, IS 33–2006.

Standing Jina, 1000–1100. India. Bronze. Courtesy of Private Collection.

The transmission of teachings, page 3 from a manuscript of the Nath Charit, 1823, by Bulaki. India. Opaque watercolor, gold, tin alloy on paper. Courtesy of Mehrangarh Museum Trust, RJS 2400.

Bhringisha and Shiva, page 304b from Teachings of the Sage Vasishta, 1602, by Keshav Das. India. Opaque watercolor, gold, ink on paper. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, f.304b.

Ascetics before shrine of the goddess, from Kedara Kalpa, approx. 1815, by workshop of Purkhu. India. Courtesy of Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland (Gift of John and Berthe Ford, 2001), W. 859.

Babur and his retinue visiting Gor Khatri, page 22b from a manuscript of Baburnama, 1590s. India. Opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, W. 596.

Maharana Sangram Singh II visiting Gosain Nilakanthji, approx. 1725. India. Opaque watercolor, gold on paper. Courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, Felton Bequest, 1980, AS92–1980.

Jallandharnath flies over King Padam's palace, from the Suraj Prakash, 1830, by Amardas Bhatti. India. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Courtesy of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, RJS 1644.

Battle at Thaneshwar, pages from a manuscript of Akbarnama, 1590–1595, by Basawan. Opaque watercolor, gold, ink on paper. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS 2:62–1896.

"Bhairava Raga," from the Chunar Ragamala, 1591. India. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS 40–1981

"Diverses Pagodes et Penitences des Faquirs", 1729, by Jean Frederic Bernard and Bernard Picart (1728). Amsterdam. Copperplate engraving. Courtesy of Robert J. Del Bontà Collection, E442.

Group of Yogis, approx. 1880s, by Colin Murray (active 1871–1884). India. Albumen print. Courtesy of Collection of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, 2011.02.02.004.

Hindoo Fakir, 1902, by Edison Manufacturing Company. United States. Film, transferred to dvd, 3 minutes. Courtesy of General Collections, Library of Congress, Washington DC, NV-061-499.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240412%2Fob_032fb1_2024-nyr-22642-0928-000-a-rare-painted.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F38%2F119589%2F129773469_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F50%2F43%2F119589%2F129706599_o.jpg)