The Morgan Library and Museum exhibits masterpieces from Oxford's famed Bodleian Library

William Shakespeare (1564–1616), Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (The First Folio) London: printed by Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623, Arch. G c.7 The Bodleian Library, Oxford.

NEW YORK, NY.- The Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford holds one of the greatest collections of books and manuscripts in the world. Marks of Genius: Treasures from the Bodleian Library, on view at the Morgan Library & Museum from June 6 to September 14, celebrates more than two thousand years of the creative genius of authors, composers, artists, scientists, and philosophers preserved in the library’s rich holdings. The exhibition includes items from cultures the world over and ranges from a papyrus fragment of a seventh-century B.C. Sappho poem to a copy of Magna Carta dating to 1217 to key works by novelist Jane Austen.

The idea of genius has always been difficult to define and its usefulness has at times been challenged. Nevertheless, the belief in its existence—as a kind of yardstick with which to measure the historical value of human achievement—has informed the building of the collections of the Bodleian and the Morgan Library & Museum. Marks of Genius speaks to the many forms the idea can take, highlighting not only the creativity of the conventional “solitary genius,” but also important innovations undertaken as collaborative efforts.

At the heart of the exhibition of almost sixty objects is the notion of genius as being broadly infused across all human endeavors.

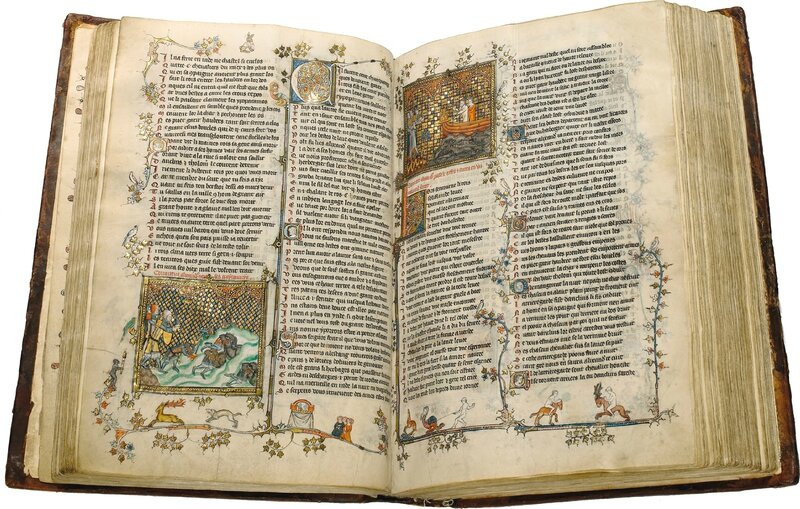

The Bodleian Library was founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, a diplomat under Queen Elizabeth I, to serve the University of Oxford and the international “republic of the learned.” In 1610 Bodley arranged an agreement with the Stationer’s Company which allowed the Library to receive copies “of all new Books”. This marks the beginning of the legal deposit and today the institution remains entitled to a copy of every book published in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Its cornerstone holdings include opulent medieval manuscripts, such as the fourteenth-century Romance of Alexander, a 1623 “copyright copy” of the Shakespeare First Folio, and part of Jane Austen’s unpublished novel, The Watsons, one of the author’s few existing manuscripts, of which the Morgan owns the other part.

“The Bodleian and the Morgan have a long history of cooperation and we are delighted to present this exceptional selection of objects from its collection,” said William M. Griswold, Director of the Morgan. “True genius is a rare and extraordinary thing. The works in this show underscore the fact that genius knows no boundaries of time, place, or culture.”

Richard Ovenden, the Bodleian’s Librarian, said, “The genius of libraries has been the preservation of the records of human civilisation. The Bodleian is proud to partner with the Morgan to bring some of the greatest of these records to New York to share with the public, through our Marks of Genius show.”

The Romance of Alexander, Flanders. Manuscript. Text completed in 1338. MS. Bodl. 264, fols. 54v–55r. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Nicholas Hilliard, Sir Thomas Bodley (1545-1613). Watercolor and gouache on parchment laid on board, 1598. LP 73. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

The Exhibition

Section I. Spirit of Place

The spirit of a place or group, which is sometimes called “genius loci,” is embodied through maps, travel accounts, and historic documents. The spirit of a nation or people can be seen in the heavily illustrated Codex Mendoza, a first-hand, historical account of Aztec Civilization produced by the Spanish colonizers around 1541, as well as one of the oldest extant copies of Magna Carta, the great English charter of freedoms, which represents the English nation much as the Declaration of Independence does the United States. Also included in this section are a six-foot-long manuscript map of the Holy Land from the late 1300s and the first map of the Virginia Colony by explorer John Smith.

Codex Mendoza, Manuscript, c. 1541. MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1, fols. 1v–2r. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Magna Carta. Manuscript. Issue of 1217. MS. Ch. Gloucs. 8. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Section II: Touch of Genius

Works in this section include Handel’s conductor’s score for Messiah used at the first performance, Moses Maimonides’s draft notes for the Mishneh Torah, and Mary Shelley’s manuscript for Frankenstein, with Percy Bysshe Shelley’s corrections.

Other objects gain authority because of their association with a historically important person. The more exceptional the individual, the more highly we value manuscripts they wrote or things they owned. Included are two books touched by legendary queens: the fourteen-year-old Elizabeth I translated a French text into English and dedicated the document to her step-mother, Katherine Parr; while St. Margaret, Queen of Scotland, owned an eleventh-century gospel book that many believe to be a holy relic.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Original draft of Frankenstein. Manuscript, December 1816 - April 1817. MS. Abinger c. 57, fols. 47–48. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Felix Mendelssohn, Schilflied (Reed Song), Watercolour/manuscript, Frankfurt, March 1845. MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn c. 101, fol. 1r. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Section III. The Patron of Genius

Books and manuscripts can be objects of great elaboration and unusual beauty. More often than not they are collaborative, and as such offer a corrective to the idea of the “solitary genius.” Many, often anonymous, hands—scribes, artists, printers, binders—produce these magnificent objects. The exquisite Hebrew Kennicott Bible from 1476 and a glorious Qur’an from 1550 speak to the genius of copying religious texts. Artistic and literary genius often needs a patron, and this relationship is fully realized in an ivory plaque from the court of Charlemagne around the year 800, the manuscript of Boccaccio’s Il Filocolo from the court of Ludovico Gonzaga, duke of Mantua, and the manuscript of Bahāristān by the Persian poet Jāmī produced at the court of Emperor Akbar in Mughal India.

The Kennicott Bible. Manuscript, Corunna, Spain, 1476. MS. Kennicott 1, fols. 5v–6r. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturale (Natural History). Printed book, Venice, 1476. Arch. G b.6, fol. 6r. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

IV. On the Shoulders of Giants

Every invention or creation is indebted to what came before. Benedictine monasticism was the cultural backbone of the Middle Ages, represented here by the oldest extant copy of the Rule of St. Benedict written in England in the early 700s. Also on view is the oldest book written in English, a translation of St. Gregory the Great’s manual on pastoral care from around 890. Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia mathematica of 1687, which laid the foundations of modern physics, had its basis in Euclid’s Elementa, composed around 300 B.C., and shown here in a copy from 888.

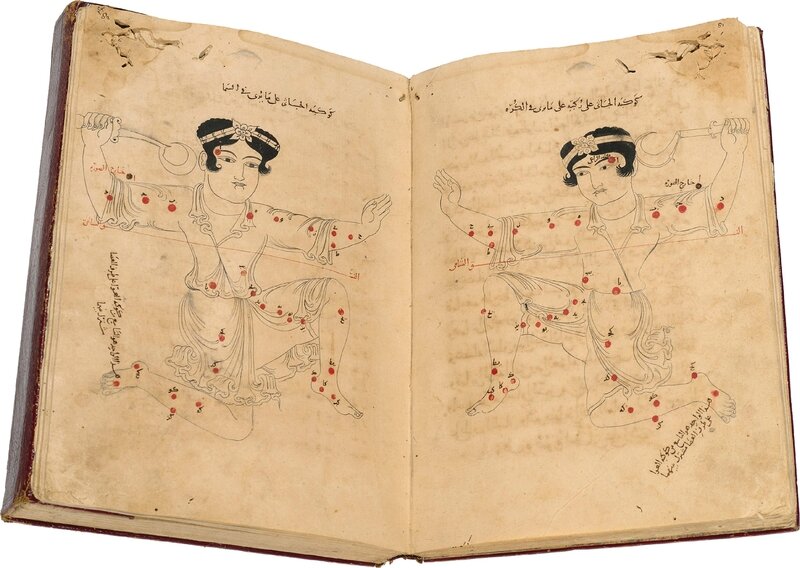

‘Abd al-Rahman al-Ṣūfī, The Book of the Constellations of the Fixed Stars. Manuscript, Twelfth century. MS. Marsh 144, pp. 81–82. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Euclid, Stoicheia (Elements). Manuscript, Constantinople, September 888. MS. D’Orville 301, fols. 113v-114r © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Section V. The Genius of Printing

Few inventions have so revolutionized the spread of knowledge, literacy, and communication as Johann Gutenberg’s creation of a system of movable type in Germany around 1450–55. Printing exponentially increased a text’s survival versus its manuscript counterpart.

Important books and ideas could suddenly circulate in hundreds of copies rather than just a handful. William Caxton was the first English printer, and the exhibition includes the first English book advertisement for his Sarum Ordinale, which can be gotten “good cheap.” A portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Julia Margaret Cameron’s photograph of Alfred, Lord Tennyson represent authors whose talents were supremely realized through print. Visually stunning works, such as Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse and J.R.R. Tolkein’s original design for The Hobbit dust jacket, illustrate the intimate relationship some authors and artists had with the publication and distribution of their own work.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Portrait of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Photograph, 1865. Arch. K b.12, fol. 78. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Albrecht Dürer, Apocalypsis (The Apocalypse). Woodcut, Nuremberg, 1511. Douce D subt. 41, fol. 5r. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F89%2F28%2F119589%2F111665508_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F30%2F119589%2F111665417_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F23%2F119589%2F32972512_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F12%2F119589%2F122358776_o.jpg)