Sotheby's sale includes masterworks from eminent aristocratic and private collections

Francisco de Zurbarán, Christ on the Cross with the Virgin, Mary Magdalene, and Saint John at his Feet. Photo Sotheby's

LONDON.- On 9th July 2014, Sotheby’s London Evening Sale of Old Master and British Paintings will be spearheaded by rare masterworks from some of the world’s most eminent aristocratic and private collections. Combining fascinating history with exceptional provenance, these works represent important moments in the artistic development of many schools and nations, from an early 14th century panel by Giovanni da Rimini from the celebrated collections of the Dukes of Northumberland to dramatic portraits from the collection of the Earls of Warwick, Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces from the collection of Barbara Piasecka Johnson and Flemish Old Master paintings from the Coppée Collection. A further highlight of this summer’s sale is one of George Stubbs’ most celebrated works and an exceptionally rare example of his big cat paintings. Comprising 63 lots, the evening sale is estimated to achieve a total in excess of £39 million.

This summer, Sotheby’s will also stage “Contemplation of the Divine” - the first ever selling-exhibition of Old Master Paintings and Sculpture held in our New Bond Street galleries, from 5th until 16th July 2014.

Discussing the forthcoming auction, Alex Bell, Joint International Head and Co-Chairman of Sotheby’s Old Master Paintings Department said: “This sale is exceptional on many levels. Having remained in the same collections for centuries, most of the works carry the imprimatur of the greatest art patrons of the day, such as the Dukes of Northumberland and the Earls of Warwick, or bear witness to the discerning eye of some of the most important collectors of the 20th century, including Baron Coppée and Barbara Piasecka Johnson. These masterworks are coming to light this summer, with their powerfully evocative beauty unaltered by the passage of time. Botticelli’s genius radiates through the extraordinarily important Study for a Seated St Joseph; Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s three iconic works from the Coppée collection encapsulate the artist’s unambiguously stark view of the human condition, while George Stubbs’ unequalled eye for capturing the animal form is reflected down to the delicate whiskers of his leopards cubs. Today, collectors from all horizons look for rare works of fantastic quality with a powerful aesthetic and both this sale and our first ever selling exhibition of Old Master Paintings and Sculpture in London have been curated with this in mind.”

PROPERTY FROM THE CELEBRATED COLLECTIONS OF THE DUKES OF NORTHUMBERLAND

Sold by Order of The 12th Duke of Northumberland and the Trustees of the Northumberland Estates

Among the paintings from the celebrated collections of the Dukes of Northumberland to be presented in the evening sale are two works formerly in the Camuccini Collection, an ensemble of outstanding works purchased by the 4th Duke of Northumberland in Rome in 1856 and representing one of the last great acquisitions made by an Englishman travelling to Italy. The first – a wing of a diptych depicting episodes from the lives of the Virgin Mary and other saints by Giovanni da Rimini - dates from circa 1300-05, a pivotal moment in European painting. The beautifully preserved panel, painted in tempera on gold ground, documents the transition from the Byzantine-inspired tradition of the dark ages to the more lyrical and naturalistic art that would herald the dawn of the Renaissance in western Europe (est. £2-3 million / €2,430,000-3,650,000 / $3,350,000-5,020,000).

Giovanni da Rimini (documented 1292 – 1309/14), Left wing of a diptych with episodes from The Lives of the Virgin and other Saints: The Apotheosis of Augustine; The Coronation of the Virgin; Catherine disputing with the philosophers; Francis receiving the stigmata; and John The Baptist in the wilderness, tempera on panel, gold ground, in an engaged frame,52.5 by 34.3 cm.; 20 5/8 by 13 1/2 in. Estimate 2,000,000 — 3,000,000 GBP. Photo Sotheby's.

This gold ground dates from 1300-05 and is mostly likely the artist’s earliest known work. Its importance as a bridge between the 13th and 14thcenturies cannot be overstated.

Its inclusion in the Camuccini collection is interesting. It is much earlier in date than anything else and does not fit the Renaissance profile of the collection. Furthermore it was not included in Barbieri's 1851 guide

Provenance: Barberini collection, Rome;

Pietro (1760–1833) and Vincenzo (1771–1844) Camuccini, Rome;

Acquired with the Camuccini collection by Algernon Percy, 4th Duke of Northumberland (1792–1865) in 1853;

Thence by descent.

Exhibited: Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Hatton Gallery, Festival of Britain Exhibition, 1951, no. 3 (here and below as Giovanni da Rimini);

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, King's College, 1955, no. 35;

Barnard Castle, The Bowes Museum, Exhibition of Dutch and Flemish Painting of the 17th Century, 1963, no. 4;

Rimini, Museo della Città, Il Trecento Riminese. Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche, 20 August 1995 – 7 January 1996, no. 14.

Literature: T. Barberi, Catalogo ragionato della Galleria Camuccini in Roma, Rome 1851, Alnwick Castle DNP: MS 810: Camera Sesta, No. 12 (as Giotto di Bondone and formerly in the Barberini collection);

Manuscript list of the pictures in the Camuccini Gallery and the prices paid, Alnwick Castle DNA:F/76A: 'Camera Sesta. 12. Giotto: Sa Caterina confonde i Dottori; di casa Barberini...£100';

G. F. Waagen, Galleries and Cabinets of Art in Great Britain, London 1857, vol. IV, pp. 465–66 (as at Alnwick and by Giotto, described as one half of a diptych, the other half of which was in the Palazzo Colonna di Sciarra);

Rev. C. H. Hartshorne, A Guide to Alnwick Castle, 1865, pp. 69–70, recorded in the Private Sitting Room of the Duchess (as Giotto);

Inventory of Pictures at Alnwick Castle, November 1894, p. 6, Sy.F.XVII.3.a(6), hanging in Her Grace's Sitting Room (as Giotto);

C. H. Collins Baker, A Catalogue of the Pictures in the Collection of the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland, London 1930, p. 137, cat. no. 648, reproduced plate 26 (as School of Rimini, 14th century, hanging in Alnwick Castle);

E. K. Waterhouse, ‘Exhibition of Old Masters at Newcastle, York, and Perth’, in The Burlington Magazine, vol. XCIII, no. 581, August 1951, p. 261 (henceforth as Giovanni da Rimini);

N. Di Carpegna, Catalogo della Galleria Nazionale. Palazzo Barberini, Rome 1953, p. 31;

G. Bandmann, ‘Zur Bedeutung der romanischen apsis’, in Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch Westdeutches Jahrbuch Für Kunstgeschichte, vol. XV, 1953, p. 43, detail reproduced p. 40, fig. 43;

S. Bottari, ‘I grandi cicli di affreschi riminesi’, in Arte antica e moderna, vol. II, 1958, p. 143, note 7, reproduced plate 43a;

F. Zeri, ‘Una Deposizione di scuola riminese’, in Paragone, vol. XCIX, 1958, p. 49;

M. Bonicatti, Trecentisti riminesi, Rome 1963, p. 6, reproduced fig. 3;

C. Volpe, La pittura riminese del Trecento, Milan 1965, pp. 15–16, 71, reproduced fig. 26;

B. Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Central Italian and North Italian Schools, London 1968, vol. I, p. 363, reproduced vol. II, plate 177;

G. Bolaffi (ed.), Dizionario enciclopedico Bolaffi dei pittori e degli incisori italiani, Turin 1974, vol. VI, p. 32;

D. Benati, ‘Pittura del Trecento in Emilia Romagna’, in La pittura in Italia, Milan 1986, pp. 157, 161;

J. Snow Smith, ‘Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks, a Franciscan Interpretation’, in Studies in Iconography, vol. 11, 1987, p. 60, reproduced pp. 66–67, figs. 16–17;

P. G. Pasini, La pittura riminese del Trecento, Rimini 1990, pp. 53–58;

M. Boskovits, ‘Per la storia della pittura tra la Romagna e le Marche ai primi del ’300’, in Arte Cristiana, vol. LXXXI, no. 775, 1993, p. 104, note 1;

D. Litte in J. Turner (ed.), The Dictionary of Art, Oxford 1996, vol. 12, p. 706;

A. Volpe in Il Trecento Riminese. Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche, exhibition catalogue, Rimini 1996, pp. 30, 37, 42, 174–75, 289, cat. no.14, reproduced in colour (as datable circa 1300–05);

A. Volpe, Giotto e Riminesi, Il gotico e l’antico nella pittura di primo Trecento, Milan, 2002, pp. 109–10, 116 and 171, note 63, reproduced in colour p. 112;

D. Ferrara in Giovanni Baronzio e la pittura a Rimini nel Trecento, exhibition catalogue, Milan 2008, pp. 86 and 88, under cat. no. 2.

Notes: This masterpiece was painted at the very dawn of the fourteenth century and is an extremely rare work by Giovanni da Rimini. It is among the very earliest Italian paintings to have been offered at auction. A very early follower of Giotto, to whom the panel was once attributed, Giovanni was undoubtedly one of the patriarchs in the relatively short-lived glory of Rimini’s school of painting in the first decades of the century. This jewel-like work is arguably the artist’s masterpiece, and it is difficult to overstate its importance as a bridge between the archaic style of the thirteenth century – still so dependent on static Byzantine models which until that moment had dominated painting in the peninsula – and the new, more recognizably Italian style bathed in emotion and perspective, which was pioneered by Giotto and which was to herald the innovations that led to the Renaissance. When Waagen (see Literature) saw the painting in 1854 he assumed it to be by Giotto's hand and described it thus: ‘...a relic of the most delicate kind, the heads fine, the motives very speaking, and the execution like the tenderest miniature...In excellent preservation’.

Roberto Longhi (see Literature) was the first to flesh out Giovanni da Rimini’s œuvre, with Brandi subsequently expanding it. First recorded in 1292, by 1300 Giovanni is referred to as a ‘maestro’ in Rimini. By the end of the thirteenth century Rimini was a small independent commune under the rule of the Malatesta family, but it was not to enjoy the wealth or verdant cultural scene from which Padua and Florence benefited until the fifteenth century. Nevertheless, the great Giotto was lured there to work for the cathedral of San Francesco, better known today as the Tempio Malatestiano. The chronicler Riccobaldo Ferrarese records that Giotto produced some superb frescoes which were most likely destroyed during the restructuring of San Francesco in 1450 but his spectacular Crucifix from just shortly before 1300 still hangs there (see fig. 1).

The date of Giotto’s stay in Rimini has been the matter of some debate, with some scholars proposing it to have post-dated his Paduan sojourn, which is generally accepted as starting after 1303. However, the date of 1309 on Giovanni's signed Crucifix in Mercatello (see fig. 2),1 so clearly dependent on Giotto’s work in the Tempio Malatestiano, strongly suggests that Giotto must have stopped in Rimini before moving on to Padua, where he was to work on the celebrated frescoes in the Cappella Scrovegni and where his colouring developed a more metallic hue, while his compositions became more daring. Moreover, among Giovanni’s most important works is the cycle of frescoes probably from the 1310s in the church of Sant’Agostino in Rimini in which the colouring and volume of the figures show to what extent Giovanni had absorbed Giotto’s pre-Paduan style; the frescoes were to prove defining for the Riminese school for some time after.

The Alnwick panel was originally the left wing of a diptych and narrates a selection of episodes from the lives of the Virgin and Saints. The right-hand panel (see fig. 3), now in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome, shows six episodes from the life of Christ. Placed side by side, the two identically-sized panels illustrate in a refined palette and with the care of a miniaturist some of the most popular and emotionally charged biblical and apocryphal scenes which presumably resonated most strongly with the Medieval believer. The present work was acquired in 1853 from the Camuccini collection, while the Rome panel was in the Sciarra collection until 1897. The early history of the paintings has not reached us but according to Barbieri in his catalogue of the Camuccini collection (see Literature), we know the Alnwick panel came from the Barberini collection. Since the Sciarra and Barberini families first intermarried in the eighteenth century, it is likely that the two leaves of the diptych were separated after a family division.2 The panels have been reunited only once, on the occasion of the 1995 landmark exhibition on fourteenth-century Riminese painting.

As was common in Romanesque panels in the Marches and in Umbria, the panels are divided into several small scenes. The Rome valve is separated into six distinct sections which are of equal size and flow in an ordered sequence from the birth of the Messiah, through to His death, Resurrection and ultimately to His seating on His throne in Heaven. The Northumberland panel, however, introduces a freer approach in both the disposition of the sections and in the choice of narrative episodes. While a very similar decorative band runs vertically through the centre of the Rome panel, in the present work it stops above the lower section of episodes, which is itself divided unevenly. The upper left section depicts the Apotheosis of Saint Augustine and is in fact made up of two quadrants extended vertically. This format creates room for the wonderfully inventive and modern temple, around which a crowd steps back in amazement as they see Augustine’s empty tomb, and allows the artist to successfully explore an early attempt at convincing perspectival solutions. Above them hovers an asymmetrical company of weightless saints and angels who surround the Virgin and Christ and welcome into their fold Augustine, seen in the centre wearing his mitre. Though the upper-right side of the panel appears to be in two sections, with a series of red crosses apparently splitting it horizontally, it is in fact a remarkably inspired reversal of the compositional layout of the Apotheosis scene: the celestial gathering of figures now appears below the focus of the scene, which in this case is the Crowning of the Virgin, rather than above it. The elegant temple, meanwhile, has been swapped for an extravagant throne so often found in Venetian painting. The lively and beautifully robed angels are again inventively irregular yet lyrically balanced in their arrangement; the central angel is even turned away and offers his back to the viewer in a wonderful early example of foreshortening in the depiction of the wings, another testament to the artist’s confident reworking of previous models.

The lower section borrows themes directly from the Saint Francis cycle of frescoes in Assisi which is generally attributed to Giotto. To the left, in the episode of The Dispute of Saint Catherine, Giovanni pays homage to the fresco of Saint Francis preaching to the Sultan (see fig. 4), both in the outstretched arms and in the architectural niche to the right. In the lower right section we see an unusual juxtaposition of Saints Francis and John the Baptist placed within a convincingly three-dimensional mountainous setting. Again, the figures of Francis receiving the stigmata and the winged cherub are lifted from the Assisi cycle (see fig. 5).

Alongside the date of 1309 on Giovanni’s Crucifix in Mercatello (fig. 2), on the basis of style works such as the Alnwick panel also lend weight to the fact that Giotto stopped in Rimini on his way to Padua – how else could artists from a relatively provincial centre such as Rimini have had access to Giotto’s designs and have been so overwhelmingly influenced so early on? Giotto’s arrival sped up immeasurably the stylistic development of the Riminese school, which subsequently plateaued fairly rapidly by the 1320s. Yet despite quickly absorbing Giotto’s modernizing tendencies, part of Giovanni’s charm and his significance to art history is that his thirteenth-century roots are inescapable: the elongated proportions of the Mercatello Crucifix and the archaic background decoration once again remind us of the Byzantine tradition which held sway over Italian painting, particularly on the Adriatic coast. Even within Giovanni’s own œuvre, his stylistic evolution is marked: possibly painted just before the Alnwick and Rome diptych, the Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels in Faenza (see fig. 6) blends a rigid and formal two-tiered structure with some startling and successful innovations, but still feels more archaic than the present work. The iconography is a development of the Byzantine Virgin Pelagonitissa, a stock type which showed the Virgin with the playing Child and which became popular in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. While the lower tier presents the figures in a somewhat austere and evenly spaced arrangement, the Madonna and Child present a strong contrast, breaking free from the tradition that had preceded them and looking toward the more expressive solutions of the fourteenth century, particularly in their tender exchange and in the form of the contorted Child.

Vincenzo Camuccini (1771–1844) was the foremost neoclassical painter in Rome, President of the Academy of St Luke and Inspector-General of the Vatican Museums, and together with his brother Pietro (1760–1833), a prominent picture dealer and restorer, amassed a very considerable collection of works of art. The greater portion of the pictures, seventy four in number, were acquired by the Duke of Northumberland, and included such masterpieces as Raphael's Madonna of the Pinks in the National Gallery in London, and Bellini and Titian's Feast of the Gods now in the National Gallery in Washington. The sale was negotiated in 1853 by Antonio Giacinto Saverio, Count Cabral, who was Northumberland's attorney in Rome, and who had valued the collection in 1850 at £2,500. Letters in the Alnwick Castle archives indicate that the sale was originally brokered by the German Emil Braun.3 The sale was made with Vincenzo's son Giovanni Battista Camuccini (1819–1904), who subsequently bought a castle at Centalupo near Rome with the proceeds.

1. The Crucifix is signed and dated: IOHANNES PICTOR FECIT HOC OPUS FRATRI TOBALDI M.L.M.CCCVIIII.

2. The case is made all the more explicit when one takes into account that Palazzo Barberini is the name of the building of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome in which the Sciarra panel hangs.

3. See J. Anderson, ‘The Provenance of Bellini's Feast of the Gods and a New/Old Interpretation’, in Studies in the History of Art.45., Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Symposium Papers, XXV, 1993, pp. 265–87.

Jan Brueghel the Elder’s The Garden of Eden – dated 1613 and painted on copper - is both a supreme example of this master’s art and depicts one of his most prized subjects. Only six recorded paintings by the Flemish artist of this subject are recorded, other examples being in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court, The Louvre, the Getty Museum and the Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome (est. £2-3 million / €2,430,000-3,650,000 / $3,350,000- 5,020,000).

Jan Brueghel the Elder (Brussels, 1568-1625 Antwerp), The Garden of Eden with the fall of an man, signed and dated lower left.: ...EGHEL 1613, oil on copper, 23.7 by 36.8 cm.; 9 1/2 by 14 1/2 in – dated 1613. Estimate 2,000,000 — 3,000,000 GBP. Photo Sotheby's

Provenance: Pietro (1760–1833) and Vincenzo (1771–1844) Camuccini, Rome;

Acquired with the Camuccini collection by Algernon Percy, 4th Duke of Northumberland (1792–1865) in 1853;

Thence by descent.

Exhibited: Barnard Castle, The Bowes Museum, From Northern Collections. Dutch and Flemish Painting of the 17th Century, Pottery and Porcelain, 7 June – 12 August 1963, no. 4;

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Hatton Gallery, Festival of Britain Exhibition, 1951, no. 3.

Literature: T. Barberi, Catalogo ragionato della Galleria Camuccini in Roma, Rome 1851, Alnwick Castle DNP: MS 810, f. 8: Camera Seconda: No. 3. Brueghel Giov: Paradiso terrestre;

Manuscript list of the pictures in the Camuccini Gallery and the prices paid, Alnwick Castle DNA:F/76A: Camera Seconda. 3. Brueghel Giov: Paradiso terrestre, nome dell'autore e la data 1613.... £100;

G. F. Waagen, Galleries and Cabinets of Art in Great Britain, London 1857, p. 471 (as at Alnwick): A pretty little picture. Signed;

Inventory of effects at Alnwick Castle, April 1865, Sy.H.IX.1.n., p. 61: Eastern Corridor. Brueghel John The Terrestrial Paradise;

Inventory of Pictures at Alnwick Castle, November 1894, Sy.F.XVII.3.a(6): Eastern Corridor. Tapestry Dressing Room. Brueghel, small picture, 'Garden of Eden';

C. H. Collins Baker, Catalogue of the Pictures in the Collection of the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland at Syon House, Alnwick Castle, Albury Park and 17 Princes Gate, London 1930, p. 14, no. 52 (as hanging in Alnwick Castle);

K. Ertz and C. Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere, vol. II, Lingen 2008–2010, pp. 442–443, cat. no. 189, reproduced.

Notes: This is one of the finest examples of Jan Brueghel’s famous 'Paradise' landscapes to remain in private hands. Transcending the tiny dimensions of the copper panel upon which it was painted, its beautifully rendered panoramic woodland setting and the lovingly detailed depiction of the teeming variety of the animal life within it, makes it easy to see why such pictures became the most famous of all the artist’s works, earning him the sobriquet ‘Paradise Brueghel’. Within these exquisite works of art Brueghel managed to give expression not only to Counter Reformation religious thought on the Creation and the natural world, but also to the burgeoning contemporary interest in the classification and representation of all its many species. From his own day to this, such works have consistently remained the rarest and most prized of all his creations.

Brueghel’s paradise landscapes such as this typically presented their subject matter within a Biblical context. Because the story of the Creation provides the Biblical link between God and the natural world, Brueghel’s concentration upon the depiction of so many animals was ideally suited to the narratives of the Book of Genesis, in this case, the Fall of Man. Here Brueghel's landscape depicts the Animal Kingdom in its harmonious state of perfection before the Fall. The viewer is at first drawn to the bewildering array of species, ranging from ostriches, a dromedary, lions and a grey horse on the left, to monkeys, cattle and leopards on the right sides of the foreground, and the eye is drawn in through a variety of birds, including swans, a peacock, heron and duck on either side of a stream into the distance goats and deer roam, and beyond them wander deer and an elephant. All around and above fly a variety of birds, familiar European species mingling with more exotic birds of paradise. And in the distant corner the eye finally alights upon the true subject of the picture, the tiny naked figures of Adam and Eve shown at the moment when they are led by the serpent to partake of the fruit of tree and thus commit the original Sin. The deliberately false insignificance of the key iconographical detail harks back to earlier Mannerist tradition and in particular the work of Jan’s father Pieter Breugel the Elder, but its presence serves to remind the viewer of his primary subject: the natural world as an expression of Divine Creation.

These elements were already in place when Brueghel painted his first paradise landscape, the Creation of Adam(Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilij) in Rome in 1594, when he was in the service of Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564–1631).1 The composition (fig. 1) is relatively awkward, with a slightly imbalanced divide between the animals and the birds and fishes, as befits a first essay in this genre. The importance of Borromeo’s patronage and influence, which would become a lifelong friendship with the artist, was to be of crucial importance in the development of Brueghel’s career and of the paradise theme itself. His philosophy provides the religious context within which Jan Brueghel's landscapes of this type would be understood. Nature and its representation in art was to be illustrative of the divine hierarchy, and the magnificence of God perceived through the contemplation of Nature. Borromeo had been particularly influenced by the thought of Filippo Neri (1515–95), the founder of the Oratorian Order, who had stressed the significance of the Creation. For Borromeo the extraordinary variety of all living species was in itself a living reflection of the Divine power of Creation. His posthumous work, I tre libri delle laudi divine (1632) encouraged the worship of God through an appreciation of his creations, and animals in particular.

‘Looking then with attentive study at animals’ construction and formation, and at their parts, and members, and characters, can it not be said how excellently divine wisdom has demonstrated the value of its great works?’

By the summer of 1596 Brueghel had returned to his native Antwerp, and by the time the present copper was painted in 1613, he had evolved a far more assured formula for the paradise theme, with both landscape and animals altogether more confidently placed in relation to each other, and the mastery of detail in their depiction complete. Works on this theme from the intervening period include a copper in the Prado in Madrid, and a circular copper in the Staatsgalerie, Neuburg an der Donau.2 The present panel belongs to a core group of pictures painted between 1612 and 1615 in which Brueghel developed his most successful designs for the Paradise landscapes. The most closely related example of this particular composition is the larger copper today in the Galleria Doria Pamphilij in Rome, which is signed and dated 1612.3 The design is broadly the same as that of the Northumberland copper from the following year, the chief differences being the changing of the positions of Adam and Eve and the greater prominence accorded the horse, dromedary and ostriches on the left of the picture. In addition to these Ertz (see Literature) also records a small (28 x 38 cm.) canvas formerly with William Doyle in New York, which closely follows the present painting, and a larger (60 x 96 cm.) panel last recorded with Goudstikker in Amsterdam, which follows the Doria Pamphilij version. Both are now known only from photographs and their autograph status remains doubtful.4 Two years later, in 1615, Brueghel returned to the theme of the Fall of Man in a copper now in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court, in which the composition is very similar but in reversed format, with the prominent grey horse and the distant figures of Adam and Eve now to be found on the right-hand side of the picture. A close replica in gouache, which Ertz assigns to the hand of Brueghel himself, was with Galerie d'Art Saint Honoré in Paris.5 The year 1615 seems to have marked the high water mark of Jan Brueghel's preoccupation with this Paradise design, for this marks the date of what is surely his largest and greatest work on this subject, the panel of Paradise landscape with the Fall of Man painted in collaboration with Rubens himself, and today in the Mauritshuis in The Hague (fig. 2).6

The enormous step up in quality between the Doria Pamphilij painting of 1594 and the present painting can of course be explained in terms of the progression of Brueghel’s own maturity, but another key factor was the influence of Rubens, with whom he had begun to work from around 1598 onwards. The magnificent grey stallion on the left of the painting, for example, is heavily indebted to Rubens’ development of this type in a number of works, chiefly equestrian portraits, and probably goes back to his studies of a Riding School, (fig. 3) painted around 1609–12 in preparation for his lost equestrian portrait of the Archduke Albert and formerly in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin.7 Similarly, the poses of the two lions beside the horse suggest strongly that Brueghel had first hand knowledge of Rubens’ own first-hand drawn studies of these beasts (London, British Museum and Vienna, Albertina)8 or else his celebrated canvas of Daniel in the Lions’ Den of circa 1612 today in Washington, National Gallery of Art.9 The presence of these animals in the Doria Pamphilij panel of 1612 show that Brueghel was familiar with their design by this date. Again, the two leopards playing on the ground on the right of the painting are also inspired by a Rubensian prototype, the Leopards, nymphs and satyrs now in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.10

Such borrowings from the work of Rubens should not be taken to infer that Brueghel’s animals were entirely derivative, for Brueghel certainly made his own studies after nature for these pictures, although very few have survived. Though none can be specifically linked to this composition, one such made in relation to his Noah and the Animals entering the Ark of 1622, now in the Getty Museum, gives a good indication of their appearance. Pen and brown ink sketches of various animals are also preserved from his visit to the court of the Emperor Rudolf II in Prague in 1604. The ostriches on the left of the picture undoubtedly reflect the result of first hand studies, such as that in pen and ink and watercolour sold New York, Sotheby’s, 20 January 1982, lot 53 (fig. 4). Brueghel’s inscription recording its size (9 voesen hooghe – nine feet high) shows quite clearly that the drawing was the result of direct observation.

As Arianne Faber Kolb has recently suggested, the prominent position occupied in the painting by both horse and lions is a direct reference to, and reflection of, their symbolic nature as royal beasts.11 Their iconographic nature as such was undoubtedly intended as a reflection of the patronage of the Archduke Albert of Austria (1559–1621) and his wife the Infanta Isabella of Spain (1566–1633), for whom Brueghel worked as court painter in Brussels between 1606 and the end of their reign in 1621. Equally importantly, it was at the Archdukes' celebrated menagerie in Brussels (fig. 5) that Brueghel would have been able to study a variety of birds and animals at first hand. From 1599 onwards the Archdukes, following in a tradition that stretched back through the Emperors Rudolf II, Maximilian I and Charles V all the way to Phillip of Burgundy, had remodelled their park to include enclosures for animals and aviaries for exotic birds. Duke Ernst Johan of Saxony, who visited Albert and Isabella in 1613, the year of this painting, described their park as filled with deer and birds, including aviaries with parrots, scarlet macaws, rare pheasants, wild and Indian pigeons, sparrow hawks from Iceland, and many ducks. By the time of theOmmeganck celebrations in Isabella’s honour two years later on 31 May 1615, at least four dromedaries had been added to the collection, and it is possible that Brueghel may have seen these too at first hand. In addition to this, of course, he may have been able to study animals in his native city of Antwerp, whose port was busy with goods from the New World, including many new and exotic species of animal.

We know that Brueghel was granted access to the menageries in Brussels, for in a letter to his earliest patron, Cardinal Federico Borromeo in Rome, written on 5 September 1621 Brueghel wrote of his delight in being able to study nature in preparation for his painting of the Virgin and Child within a garland of flowers (Madrid, Museo del Prado) in which 'the birds and animals were done from the life from several of her Serene Highness's specimens'.12 If Borromeo’s philosophy provided the religious context within which Brueghel’s paradise landscapes would have been understood by his contemporaries, the patronage of the Archdukes was of equal importance, for it connected Brueghel to the contemporary growth and extension of enquiry into the natural world and the classification of its contents. This trend manifested itself not only in the collection of animals in the menagerie of the Archdukes, but also in the appearance of the first scientific collections and the publication of the first natural history catalogues, notably those by Conrad Gesner (1516–65), the Swiss naturalist whose famous ground breaking encyclopaedia, the Historiæ Animalium was printed as early as 1551–58, and the Bolognese scholar Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) whose Ornithologiæ was published in 1599–1603. These were the first comprehensive works on natural history since Pliny’s Historia Naturalis (A.D. 77), and the first to apply an extensive system of description for each animal. From these sources Brueghel seems to have adopted the idea of grouping the animals together in their basic groups and depicted them correctly in their specific natural habitat. This classifying tendency was strongest in other works closely related to the paradise landscapes, most notably Brueghel’s series of paintings of the Elements and those devoted to the story of the Entry of the Animals into Noah’s Ark, notably for example, those of 1613 in the Getty Museum in California and of 1615 in Apsley House, London. Brueghel was by no means the first artist to treat the theme of the landscape of paradise, nor the first to closely observe wild animals, but his study of the animals in the Archdukes’ menagerie and the growing intellectual background against which such studies were set, gave his paradise landscapes such as this a realism and an accuracy in the depiction of the various species depicted that had never been seen before. Brueghel’s own highly detailed and finished style was ideally suited to this task.

Sadly, the earliest history of this painting is as yet unknown. It entered the Northumberland collections, of course, with the acquisition by the 4th Duke of the inventory of the gallery of the Camuccini brothers in Rome in 1853. The date of its acquisition or purchase by the Camuccini brothers is not known, but it is not impossible that the painting had been in Rome from an earlier date. Brueghel’s first paradise landscape, that in Galleria Doria Pamphilij in Rome is recorded in the collection of Cardinal Camillo Pamphilij (d. 1666) in 1654 and may well have been painted there for Cardinal Federico Borromeo. The other version of this composition, the larger panel in the same collection, is also recorded in the same inventory. Camillo’s letters, as well as subsequent family inventories, suggest that he acquired most of the paintings by Brueghel in the family collection, including a famous set of the Four Elements, painted around 1610–11 and which remain in the family collection to this day.

1. Copper, signed and dated 1594, 26.5 x 35 cm. Reproduced in K. Ertz and C. Nitze-Ertz, under Literature, 2008–10, pp. 432–33, no. 185.

2. Ertz and Nitze-Ertz, op. cit., 2008–10, pp. 434–37, nos. 186 and 187, reproduced.

3. Copper, 50.3 x 80.1 cm., signed and dated 1612, ibid.,pp. 440–42, no. 188.

4. Ibid., nos. 190 and 191.

5. Ibid., nos. 192 and 193.

6. P. Van der Ploeg and Q. Buvelot, Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis. A Princely Collection, The Hague 2006, pp. 74–76, reproduced.

7. H. Vlieghe, Rubens Portraits. Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, Part XIX, vol. II, London 1987, p. 36, fig. 4.

8. J. S. Held, Rubens. Selected Drawings, London 1959, vol. I, p. 131, cat. no. 83, and vol. II, Frontispiece and plate 96.

9. Washington, Alicia Mellon Bruce Fund, inv. no. 1965.13-1. Canvas, 224 x 390 cm. For which see M. Jaffé, Rubens. Catalogo completo, Milan 1989, p. 202, no. 289, reproduced.

10. Jaffé, op. cit., 1989, p. 203, no. 289bis, reproduced.

11. A. Faber Kolb, Jan Brueghel the Elder: The Entry of the Animals into Noah's Ark, Getty Museum Studies on Art, Los Angeles 2005.

12. Cited by A. van Suchtelen, in the exhibition catalogue,Rubens and Brueghel. A Working Friendship, Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2006, p. 69, n. 39.

From a different place and era is a fascinating portrait of Mohawk War Chieftain Thayendanegea (to whom the English gave the name Joseph Brant), commissioned by Hugh Percy, the 2nd Duke of Northumberland from the American artist, Gilbert Stuart in 1786 (est. £1-1.5 million / €1,220,000-1,830,000 / $1,680,000-2,510,000). An interpreter for the British Indian Department, Brant assisted the British in the American War of Independence in order to regain land that had been lost by the Mohawk people. He fought alongside the 2nd Duke at the Battle of Long Island, New York in 1776 and was described at the time as “The perfect soldier, possessed of remarkable stamina, courage under fire, and dedicated to the cause, an able and inspiring leader and a complete gentleman.” Despite the fact that he was widely admired by many of his English compatriots, his closest, and indeed only, enduring friendship with a white man was with Hugh Percy.

Gilbert Stuart (Saunderson, Rhode Island 1755 -1828 Boston), Portrait of the Mohawk Chieftain Thayendanegea, known as Joseph Brant (1742–1807), inscribed, verso, on the relining: Joseph Theanandagen (commonly called Capt Brandt [sic]) Chief Warrior of Sachem of the Mohawk / Nation of Indians who served with the Duke of Northumberland in America in the Year 1776 / Transcribed 27th June 1955, oil on canvas, 76.2 by 61 cm.; 30 by 25 in. Estimate 1,000,000 — 1,500,000 GBP. Photo Sotheby's

Provenance: Commissioned in 1786 by Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland (1742-1817);

By descent to his son, Hugh Percy, 3rd Duke of Northumberland (1785–1847);

By inheritance to his brother, Algernon Percy, 4th Duke of Northumberland (1792–1865);

By inheritance to his cousin, George Percy, 5th Duke of Northumberland (1778–1867);

By descent to his son, Algernon George Percy, 6th Duke of Northumberland (1810–1899);

By descent to his son, Henry George Percy, 7th Duke of Northumberland (1846–1918);

By descent to his son Alan Ian Percy, 8th Duke of Northumberland (1880–1930), who married Helen Gordon-Lennox (1886–1965), daughter of Charles Gordon-Lennox, 7th Duke of Richmond;

By descent to their second son, Hugh Algernon Percy (1914–1988), who succeeded his brother, the 9th Duke, as 10th Duke of Northumberland in 1940, after he was killed in action whilst serving with the Grenadier Guards during the retreat to Dunkirk;

By descent to his son, Henry Alan Walter Richard Percy, 11th Duke of Northumberland (1953–1995);

By inheritance to his brother, Ralph George Algernon Percy, 12th and present Duke of Northumberland (b. 1956), the current owner.

Exhibited: London, British Institution, 1857, no. 110;

London, Christie’s, 24 August – 25 September 1960;

Washington, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1 May 1976 – 1 April 1977;

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilbert Stuart, 18 October 2004 – 27 February 2005, no. 17;

Washington, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, Gilbert Stuart, 8 April 2005 – 31 May 2005, no. 17;

Washington, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, American Origins 1600–1900, 2006, no. 66.

Literature : W. L. Stone, Life of Joseph Brant – Thayendanegea, including the Border Wars of the American Revolution, 2 vols., New York 1838, vol. I, p. xxviii, vol. II, pp. 251 and 337;

Alnwick Castle, Sy.H.VIII.1.b, Syon House Inventory, 1847, p. 212;

M. Fielding, 'Paintings by Gilbert Stuart not mentioned in Mason's Life of Stuart', in Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1914, vol. 38, pp. 311–34;

M. Fielding, 'Addenda and Corrections to Paintings by Gilbert Stuart not noted in Mason's Life of Stuart', Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1920, vol. 44, pp. 88–91;

L. Park, Gilbert Stuart. An illustrated descriptive list of his works, New York 1926, vol. II, p. 747, no. 831, reproduced, vol. IV, p. 516;

C. H. Collins Baker, A Catalogue of the Pictures in the Collection of the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland, London 1930, cat. no. 702 (hanging at Albury Park).

J. R. Fawcett Thompson, ‘Thayendanegea the Mohawk and his several portraits. How the ‘Captain of the Six Nations’ came to London and sat for Romney and Stuart’, in The Connoisseur, vol. 170, January 1969, p. 51, reproduced fig. 3;

D. Evans, The Genius of Gilbert Stuart, Princeton 1999, p. 44, reproduced p. 45;

C. R. Barratt and E. G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2004, pp. 68–71, reproduced in colour p. 69.

Notes: "Our wise men are called Fathers, and they truly sustain that character. Do you call yourselves Christians? Does the religion of Him who you call your Saviour inspire your spirit, and guide your practices? Surely not.

It is recorded of Him that a bruised reed he never broke. Cease then to call yourselves Christians, lest you declare to the world your hypocrisy. Cease too to call other nations savage, when you are tenfold more the children of cruelty than they.

No person among us desires any other reward for performing a brave and worthwhile action, but the consciousness of having served his nation.

I bow to no man for I am considered a prince among my own people. But I will gladly shake your hand."

Joseph Brant to King George III, 1786

Painted in 1786, whilst the sitter was on his second visit to England, this powerfully evocative painting is possibly the finest portrait of one of the seminal figures of early American history. The paramount war chief of the Iroquois Nation, as well as a missionary and diplomat of consummate skill, Thayendanegea was the Native American best known to Europeans of his generation. An inspirational leader, he lobbied tirelessly with both British and American authorities to secure his nation's survival. Commissioned by his close friend and old comrade in arms, Hugh, Earl Percy, later 2nd Duke of Northumberland (1742–1817: see fig. 1), whilst Brant was in London in the winter of 1785–86, negotiating land claims with the British Crown, this portrait is a visual expression of a fraternal bond forged in adversity, and a friendship that traversed culture, race and an ocean. Brant and Percy had met in 1776 when both commanded allied troops around Boston and New York during the American Revolution. By repute Brant is believed to have been with Percy in the flanking movement that cut through the Jamaica Pass during the Battle of Long Island, when British forces under General Howe retook New York, and the pair formed a bond that led to Percy’s adoption by the Mohawk as a warrior of their nation, under the name Thorighwegeri (or The Evergreen Brake, implying ‘a titled house that never dies’).1 Following Percy’s return to England they kept up a lifelong correspondence and exchange of ceremonial gifts. In the Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto, are a pair of flintlock pistols, inlaid with silver escutcheons engraved with the letter 'N' surmounted by ducal coronets, that were sent by Percy, by then Duke of Northumberland, to Brant in 1791. The many surviving letters between the two, several of which can be found in the British Museum, as well as in various archives in America, convey a strong mutual respect and a genuine affection on both sides, in what was to be Brant’s only lasting friendship with a white man.

Born in 1742 on the banks of the Cayahoga River, Ohio, Thayendanegea, known to the English as Joseph Brant, was the son of Tehowaghwengaraghkwin, a prominent Mohawk warrior. From his mother, Owandah, he descended from the Mohawk chief Theyanoguin and was born into the Mohican Wolf Clan, one of the chief tribes of the Iroquois Nation. His name, Thayendanega, translates as 'two sticks bound together', or 'he who places two bets' denoting strength and wisdom. Anglican Church records at Fort Hunter, New York, show that his parents were Christians whose English names were Peter and Margaret, but that his father died when he was still in infancy. Details of his early years are scarce, but at some point after his father’s death Joseph’s mother took him and his elder sister, Konwatsi’tsiaienni, known as Molly or Mary, to live with her people in the Mohawk Valley, and in 1753 remarried a widower named Canagaraduncka, a Mohawk sachem, or paramount chief, who was known to the whites as Barnet, or Bernard, and by contraction Brant. As such, young Joseph became known to the whites as Brant’s Joseph, and later Joseph Brant.

Brant’s step father had connections with the British, his grandfather having been one of the Four Mohawk Kings who visited England in 1710 (fig. 5), and was a friend of the influential and wealthy General Sir William Johnson (circa1715–74), Superintendent for Indian Affairs in the Northern Colonies. During Johnson’s frequent visits to the Mohawk he stayed with the Brants’ at Canajoharie, on the banks of the Mohawk River, and formed a relationship with Joseph’s sister Molly, with whom he lived as his common-law wife from 1763. Molly became something of a legendary figure in her own right and lived publically with Johnson, managing his estate during his many absences and running his household, as well as bearing him nine children. Through Johnson’s influence Brant became acquainted from a young age with many influential white figures within the New York colony, and the Superintendent took a personal interest in the young boy’s development and education. In 1761 Johnson arranged for Brant, along with two other Mohawk boys, to be educated by Dr Eleazar Wheelock, at Moor's Indian charity school in Connecticut, the precursor to Dartmouth College. He learned to speak, read and write English fluently, as well as being taught a number of other academic subjects. Brant's clear intelligence and diligence greatly impressed Wheelock, who described his promising student as being 'of sprightly genius, a manly and genteel deportment, and a modest and benevolent temper',2 and planned to send him to college in New Jersey.

A warrior noted for his bravery, as well as a distinguished missionary and diplomat in later life, Brant's rise to prominence began at an early age. His first military service came with the outbreak of hostilities between the French and British in North America in 1754. Early in what is referred to in America as the French and Indian Wars, part of the greater global conflict of the Seven Years War, Brant joined the Mohawk war parties which, along with other tribes of the Iroquois nation, allied themselves with the British. At only fifteen he took part in Major-General James Abercrombie's campaign to cross Lake George and invade French Canada, and in 1758 was one of the Iroquois warriors under the command of Sir William Johnson who accompanied General Jeffrey Amherst’s expedition against Fort Niagara, near present day Youngstown. The following year Brant was again with Amherst when he led a force of British regulars and local rangers down the St Lawrence River to besiege and capture Montreal, thereby ending French hegemony in North America, and was one of the 182 Native American warrior's to be awarded a silver medal by the British for his service.

Brant's intelligence and inspirational leadership inspired the esteem and respect of both his own Native American warriors and their British allies. As well as speaking English he was fluent in at least three, if not all of the Six Nation Iroquoian languages that made up the Iroquois confederacy, and from 1766 Brant worked as an interpreter for the British Indian Department. In the Spring of 1772 he moved to Fort Hunter, in upstate New York, where he collaborated with the Reverend John Stuart, an Anglican missionary, on the translation of the catechism of the Book of Common Prayer, as well as other Christian texts. With his learning and language skill, and his connections with the British, Brant rose swiftly through tribal ranks to become one of the leading war chiefs of the Iroquois nation, and with Johnson's encouragement, the primary spokesman for the Mohawk in Anglo-Indian relations. In 1775, with rising tensions between the American colonists and the British authorities, Brant, who remained loyal to the Crown, was appointed ‘Interpreter for the Six Nations Language’, at an annual salary of £85. 3s. 4d. In November of that year he travelled to England with Guy Johnson (1740–88), Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs and Sir William’s nephew, to petition the British government for aid (fig. 2). Specifically Brant hoped to secure assurances of support from the Crown in redressing past Mohawk land grievances against American colonists, in return for Iroquois military support in the coming conflict.

In London Brant's combination of civilised erudition and savage romanticism created a sensation, and he was universally lionised by both politicians and the beau monde. With his customary charisma and keen comprehension for cultural difference he adopted English style politeness for his negotiations with Lord Germain, Secretary of State for the American Colonies, whilst dressing in full Iroquois chieftain’s dress when in public. The Earl of Warwick commissioned Brant's portrait from George Romney (fig. 3: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa), he was inducted into the Freemason’s, and was received at court by George III at St James’s Palace. The King presented Brant with the silver gorget, emblazoned with the Royal crest and inscribed ‘The Gift of a Friend to Capt. Brant’, which he is depicted wearing in this portrait, accompanied by a portrait cameo of the monarch.3 George was sympathetic to the Indian cause, and Brant returned home in June 1776 with the reassurances of protection for his people and their land which he had sought. In a letter Lord Germain further guaranteed that, in return for the loyalty of the Six Nations, the Iroquois could be assured ‘of every support England could render them’.4

Brant landed back in North America in July 1776, in time to join General Howe’s forces as they prepared to retake New York. Though there is no official record of his service, it is here, under the command of Generals Clinton and Cornwallis, that he is believed to have first made the acquaintance of the man that would become his greatest friend among the whites, Hugh, Earl Percy. Percy commanded six battalions, as well as a contingent of artillery, in the column that marched through the night at Jamaica Pass to attack the Americans’ flank on 27 August 1776. The plan was audacious, requiring knowledge of the local terrain, and Brant is believed to have led a party of Mohawk warriors in the attack, and distinguished himself for bravery. In November, following the capture of Fort Washington, at the northern end of Manhattan Island, in which Percy led the charge, Brant travelled north, raising a force of Mohawk warriors and white loyalist militia. Known as Brant’s Volunteers they operated out of Onoquaga, an Iroquois village on the Susquehanna River, and in the summer of 1777 joined forces with British regulars under Brigadier General Barry St Leger to besiege Fort Stanwix, defeating a Continental Army led by Nicholas Herkimer (circa 1728–77) at the Battle of Oriskany on 6 August. In July that year Brant had finally persuaded the council of the Six Nations to abandon their neutrality, and enter the war on the British side. For the next six years he led Iroquois forces in a dazzlingly successful campaign throughout the Mohawk Valley and the area around the Great Lakes in support of the British. One of the most active partisan leaders in the frontier war, in April 1779 Lord Germain sent the governor of Quebec, Frederick Haldimand, a commission signed by George III, appointing Brant Colonel of Indians, in recognition ‘of his astonishing activity and success in the king’s service’.5 The document was suppressed, however, for fear of creating resentment among the other leading Iroquois warriors, and it was not until July 1780 that Brant received an official commission, when (at the recommendation of Guy Johnson) he was appointed Captain of the Northern Confederate Indians. Despite the delay in official recognition, however, Brant was widely praised for his leadership and skill, and British officers who served with him always had the highest praise for his abilities. He was described in official dispatches as ‘the perfect soldier, possessed of remarkable physical stamina, courage under fire, and dedication to the cause, as an able and inspiring leader, and as a complete gentleman’.6 Indeed white volunteers are known to have requested to fight under his command among Iroquois war parties, rather than serve in the rangers, such was their confidence in his abilities.

Following the treaty of Paris in 1783, which despite pre-war British promises made no provision for the welfare or sovereignty of their Native Americans allies, or showed any concern for the economic viability of the Six Nations, Brant travelled to England a second time to again petition the Crown on behalf of the Iroquois. In London he was once more feted by high society, and hailed as the ‘king of the Mohawks’. The reputation and fame he had acquired during the war meant that he was held in high esteem by the British aristocracy, and he used the opportunity to reacquaint himself with many of the British officers with whom he had served in North America. At court Brant ‘presented a seductive public image that merged diplomat and warrior, gentleman and brute’,7 astutely adapting Iroquois custom and dress to suit the occasion. The Baroness von Riedesel, who had known Brant in North America, described the magnificence of the spectacle he presented in her diary: ‘I saw… the famous Indian Chief, Captain Brant. I dined once with him at the General’s. In his dress he showed off to advantage the half military and half savage costume. His countenance is manly and intelligent, his disposition very mild. His manners are polished and he expresses himself with fluency’.8 It was a display that clearly impressed the teenage Prince of Wales, later George IV, who took Brant on many excursions in the capital, and he was much in demand in the salons of the establishment, even attending a masquerade ball.9 This second visit also afforded the opportunity for Brant to reacquaint himself with old comrades who had served with him in North America, and in particular his blood brother Percy, who took the opportunity to commission the great American portrait artist Gilbert Stuart to paint Brant's likeness.Stuart, who had moved to London in 1775, was also commissioned to paint Brant’s portrait by Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings (1754–1826), who, like Northumberland, had seen active military service in North America during the revolution (fig. 4: Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y.). His exotic appearance was clearly an appealing subject for artists and Brant also sat to John Francis Rigaud whilst in London. The portrait depicted him in the uniform of an officer on the British Indian Department, together with an Iroquois headdress, and was exhibited at the Royal Academy in the summer of 1786 (whereabouts unknown).

Both Stuart’s portraits of Brant reinforce his Native American heritage, but it is only in the Northumberland portrait that the purpose of Brant’s embassy to London, and his allegiance with the British, is made explicit. With a fully modelled visage that portrays a man of intelligent determination, Brant is depicted in the costume of an Iroquois chieftain, his clothing proclaiming both his nationality and his dignity. The silver rings embroidered into his clothing, his plumed headdress, and the silver amulets on his upper arms and wrists all declare his high rank and status. Around his neck, suspended by a blue ribbon, he wears the gorget presented to him by George III, with a medallion portrait of the King in an imposing brass locket below, clearly demonstrating his political allegiance. He is, as Carrie Rebora Barratt wrote in her catalogue entry to the 2004 exhibition, ‘by Stuart’s brush, the exemplification of the savage and noble, an Iroquois statesman ornamented by the British. He entertains the royal encomiums, even as his poignant facial expression seems to acknowledge the equivocation in the King’s promises of assistance’.10 More than this, however, the painting is a statement of fraternity and eternal friendship; a token of affection between an English Lord and his brother warrior in the forests. Clearly it was an object which Percy held in high regard, for he mentions it in a letter to Brant in 1791 stating ‘I preserve with great care your picture, which is hung in the Duchess’s own room’, signing the letter ‘continue to me your friendship and esteem, and believe me ever to be, with the greatest truth, Your affectionate, Friend and Brother, Northumberland, Thorighwegeri’.11

Returning to North America in June 1786, Brant settled in Quebec, from where he continued to campaign tirelessly on the issue of Indian land sovereignty. Negotiating both with the British and the American Governments, in 1792 he travelled to Philadelphia to meet George Washington and negotiate Mohawk land claims in upstate New York. Though not a hereditary sachem (paramount chief) Brant’s education, fluency in English, and his many contacts with government officials in England and Canada, as well as his knowledge of the laws and customs of the whites, meant that he was entrusted as one of the primary spokesmen for his people. In the many territorial negotiations with the governments of Canada and United States that would be held in the years to follow, it was to Brant that the chiefs entrusted their diplomacy. In 1795 Brant secured a large tract of land from the Mississauga Indians, in the vicinity of Burlington Bay, on Lake Ontario, where he built a fine house and lived in genteel English style. He never forgot the cause of his people, however, and would actively pursue recognition of Indian rights until his death in 1807, at the age of 64.

Educated at Eton and St John’s College Cambridge, Hugh, Earl Percy, later 2nd Duke of Northumberland, was gazetted into the army in 1759 at the age of sixteen, first as an ensign in the 24th Regiment of Foot, and later that year as captain of the 85th. In 1762 he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel of the newly raised 111th Regiment of Foot, and shortly afterwards received a commission in the Grenadier Guards. In 1764 he married Lady Anne Stuart, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Bute (1713–92), though they were soon divorced, and was appointed aide-de-camp to the King, George III. Despite being elected to parliament in the 1774 general election, in May of that year Percy left with his regiment for service in North America. As a commander he was hugely admired by his troops, marching on foot alongside them and maintaining a vigilant eye on their welfare. He would often furnish his men with food and clothing at his own personal expense, and is known to have paid the cost of the return passage home for those widows whose husbands had died in his service. Extravagant and generous, he was one of the richest men in England and an important and long standing sponsor of Gilbert Stuart’s, whom he rescued from debt in 1785 and who took on something of a role akin to that of a court painter to the Percy household. Percy was therefore a crucial early patron of an artist who went on to become one of the greatest American portrait painters in history. As well as the portrait of Joseph Brant, Stuart painted several half-length portraits of the Duke himself, full-length portraits of the Duke and the Duchess, as well as a large scale portrait of his four children (Northumberland Collection, Syon House).

1. W. L. Stone, Life of Joseph Brant – Thayendanegea, including the Border Wars of the American Revolution, 2 vols., New York 1838, vol. II, p. 337.

2. B. Graymont, 'Thayendanegea', in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. V, University of Toronto, online version.

3. Brant’s gorget is now in the Rochester Museum and Science Centre, Rochester, New York.

4. B. Graymont, op. cit.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. C. R. Barratt and E. G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart, exhibition catalogue, New York 2004, p. 70.

8. Quoted in L. A. Wood, The War Chief of the Six Nations. A Chronicle of Joseph Brant, Toronto 1914, p. 109.

9. An account of which is given in W. L. Stone, Life of Joseph Brant – Thayendanegea, including the Border Wars of the American Revolution, 2 vols, New York 1838, vol. II, p. 259.

10. C. R. Barratt and E. G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart, exhibition catalogue, New York 2004, p. 71.

11. Quoted in W. L.Stone, Life of Joseph Brant – Thayendanegea, including the Border Wars of the American Revolution, 2 vols., New York 1838, vol. II, pp. 337–38.

RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE MASTERWORKS FROM THE COLLECTION OF BARBARA PIASECKA JOHNSON

Sold to Benefit The Barbara Piasecka Johnson Foundation

The sale will also present nine Renaissance and Baroque masterworks from the Estate of Barbara Piasecka Johnson (1937-2013) - art connoisseur, philanthropist and wife of the late John Seward Johnson, heir to the Johnson and Johnson medical and pharmaceutical firm. The group is led by three remarkably rare Florentine drawings, including the only Botticelli drawing to appear on the market in a century (est. £1-1.5 million / €1.2-1.8 million / $1.7-2.5 million) and two magnificent drapery studies, executed circa 1470 in one of the most important workshops of the Renaissance, the bottega of Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-1488) (est. £1.5-2 million each, €1.8-2.4 million/ $2.5-3.4 million). In addition to the Renaissance drawings, the selection features an extraordinary depiction of The Sacrifice of Isaac by Caravaggio’s gifted follower, Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, which is the most important and powerful Italian Caravaggesque painting to appear on the open market in a generation (est. £3-5 million / €3.7-6 million / $5-8.4 million). The proceeds of the sale, expected to fetch over £8.6 million, are to benefit the Barbara Piasecka Johnson Foundation, the primary focus of which is helping children with autism.

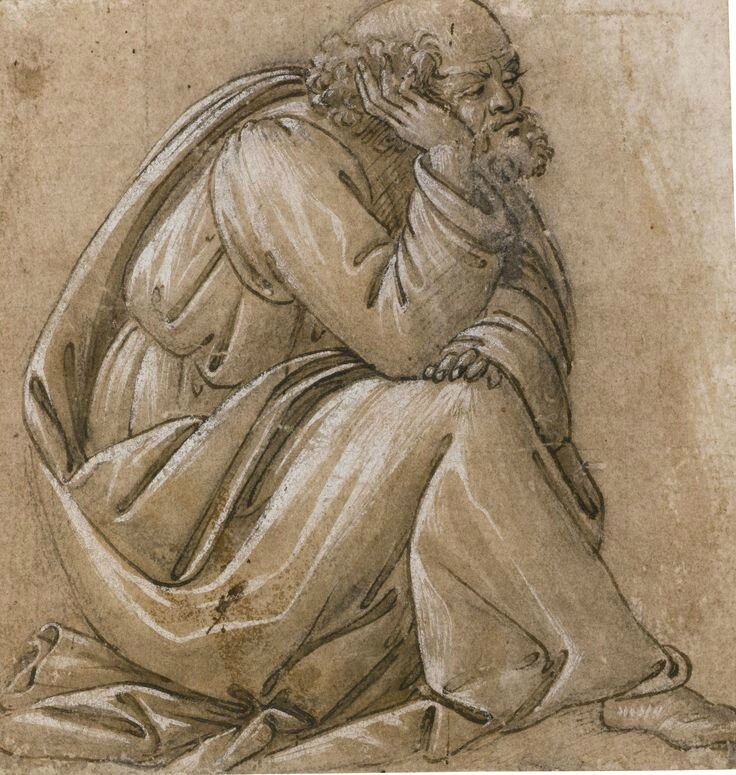

Sandro Botticelli (Florence 1444/5-1510), Study for a seated St Joseph, his head resting on his right hand, Pen and brown ink heightened with white over black chalk, on beige-pink washed paper. Squared in black chalk for transfer;bears attribution in pencil at the bottom: Giotto, 129 by 124 mm. Estimate 1,000,000 — 1,500,000 GBP. Photo Sotheby's

Provenance: George Le Hunte of Artramont, County Wexford,

thence by descent to the Misses M. H., L. E. and M. D. Le Hunte,

their sale and others, London, Sotheby's, 9 June 1955, lot 45 (as Workshop of Sandro Botticelli, purchased by Hewett, £ 300);

Miss A.J. Martin;

sale, London, Sotheby's, 26 June 1957, lot 10 (as Workshop of Sandro Botticelli, purchased by Tooth, £ 290);

with William Schab Gallery, New York, Master Drawings and Prints, 1960;

Benjamin Sonnenberg, his sale New York, Sotheby's, 5-9 June 1979, lot 125 (as Circle of Botticelli, $26,000);

sale, New York, Sotheby's, 13 January 1988, lot 88 ($ 80,000);

Barbara Piasecka Johnson

Exhibited: Poughkeepsie, New York, Vassar College Art Gallery, and New York, Wildenstein and Co., Centennial Loan Exhibition, 1961, no. 2, reproduced;

Warsaw, The Royal Castle, Opus Sacrum from the Collection of Barbara Piasecka Johnson, 1990, pp. 94-97, note 14 (entry by K. Oberhuber), reproduced p. 95;

Warsaw, The Royal Castle, The Masters of Drawing, Drawings from the Barbara Piasecka Johnson Collection, 2010-11, pp. 38-39, reproduced p. 39

Literature: R. Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli, Life and Works, London 1978, vol. II, p. 138, under no. C42;

The Faringdon Collection, Buscot Park, 1990, p. 47, under no. 47;

Buscot Park, The Faringdon Collection, 2004, p. 63, under no. 47

Notes: A very rare late drawing by Sandro Botticelli, the present sheet is closely related to the figure of St. Joseph to the left of The Nativity with adoring St John the Baptist, at Buscot Park (fig. 1), a tondo now believed to be a substantially autograph work by the artist, dating from the late 1480s. It seems to be the only surviving drawing by Botticelli that can be clearly linked with one of his paintings, and is also the only study by the artist that remains in private hands. The drawing, squared for transfer, shows minor but significant differences from the final painted work, especially in the position of the head of St. Joseph, which is higher and slightly tilted to the right. Moreover, some faint chalk lines, noticeable to the right of St. Joseph's head, indicate a revision in the position of his head, which appears initially to have been drawn leaning forward and turned, looking down towards the Child, an interesting but discarded alternative.

When the drawing was last sold in 1988 (see Provenance) the attribution to Botticelli was fully endorsed by Philip Pouncey and other scholars, and the study was rightly associated with the graphic style of the late Botticelli, although mistakenly believed to relate to the figure of St. Peter in the artist's painting, The Agony in the Garden, now in the Royal Chapel, Granada (fig. 2).1

In this remarkable drawing, the strong and firm contours are animated by deep and sculptural folds, executed in pen and ink, suggesting St. Joseph's seated pose and his abundant garments. The figure retains a strongly Gothic flavour and rhythm in its essential elegance and fluency of lines. The severity and solidity of the image is softened by the intricacy of the folds, and it is also lightened by the very dynamic and skilfully applied white heightening. The latter contrasts strikingly with the black chalk underdrawing, and with the parallel pen lines in the upper part of St. Joseph's body and sleeves, used most effectively to emphasize areas of shadow, which correspond closely with those seen in the Buscot Park painting. The use of abundant parallel lines is also noticeable in Botticelli's late allegorical figure of Faith, now in the British Museum, London, datable to circa 1490-1500.2 A further stylistic comparison can be made with another late study for a kneeling male figure, executed in the same media as the present sheet, now in the Ambrosiana.3 The subject of the Ambrosiana sheet was rightly identified by Berenson as St Thomas receiving the Virgin's girdle, and associated with the Botticellesque engraving of The Assumption of the Virgin, of circa 1495.4

Botticelli has here washed the paper in a beige-pink colour, leaving this grounding slightly unfinished to the right edge of the sheet. He possibly felt no need to complete the preparation which seems to be applied solely to enhance the coloristic effects achieved by the combination of other media that the artist has employed. This is most certainly a working drawing, but is also the type of record-drawing that the workshop of Botticelli would have used over and over again, also with some slight variations. The practice of creating a graphic archive, often preserved in albums or ‘pattern books,’ was common in the botteghe of the 15thcentury. It was not only a way to preserve and disseminate the master's style, but also a practical way to speed up the process when looking for motifs to incorporate in some newly-created composition. Such a finished drawing would certainly have been preserved in an album of this type.

Although this studio practice should have ensured the preservation of Botticelli's drawings, of which, according to Giorgio Vasari’s life of the artist, there were originally a substantial number, today only around a dozen original sheets are known to survive, plus the famous series of ninety-two drawings that Botticelli made around 1480-95 to illustrate Dante's Divina Commedia, drawings that are now divided between the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin, and the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.5 Vasari writes: Disegnò Sandro bene e fuor di modo, e tanto, che dopo lui un pezzo s'ingegnarono gli artefici d'avere de' suoi disegni; e noi nel nostro Libro n'abbiamo alcuni che son fatti con molta pratica e giudizio.6

The present sheet seems to be the only drawing that can be directly connected with one of Botticelli's painted compositions, which makes it an extraordinary and important testimonianza of the artist’s working method. In its restrained style this sheet testifies to the severe influence and profound spiritual crisis which affected Botticelli at the time of Savonarola (1452-98), the Dominican reformer and preacher who ruled the city of Florence in the mid-1490s.

The present sheet seems to be the only drawing that can be directly connected with one of Botticelli's painted compositions, which makes it an extraordinary and important testimonianza of the artist’s working method. In its restrained style this sheet testifies to the severe influence and profound spiritual crisis which affected Botticelli at the time of Savonarola (1452-98), the Dominican reformer and preacher who ruled the city of Florence in the mid-1490s.

1. R. Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli, Life and Works, London 1978, reproduced vol. I, pl. 50

2. inv. no. 1895, 0915.448; H. Chapman and M. Faietti, Fra Angelico to Leonardo, Italian Renaissance Drawings, exh. cat., London, British Museum, 2010, and Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, 2011, p. 179, no. 38, reproduced

3. Codice Resta, f.14.bb. 569; G. Bora, I disegni del Codice Resta, Bologna 1976, 18, p. 14

4. G. Mandel, L'opera completa del Botticelli, Milan 1978, reproduced p. 117

5. Lightbown, op. cit., vol. I, pp. 147-151 and Sandro Botticelli, The Drawings for the Dante's Divine Comedy, exhib. cat., London, Royal Academy of Arts, 2000

6. G. Vasari, Le Vite de più eccellenti pittori scultori ed architettori, ed. G. Milanesi, Florence 1878, vol. III, p. 323

Workshop of Andrea Del Verrocchio, circa 1470, traditionally attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci, Drapery study of a kneeling figure facing left. Drawn with the brush in brown-grey wash, heightened with white, on linen prepared grey-green, laid down on paper; Numbered in brown ink: X, 288 by 181 mm. Estimate 1,500,000 — 2,000,000 GBP. Photo Sotheby's

Provenance: Everhard Jabach, his posthumous inventory of 1695, as Dürer,

thence by inheritance to his widow Anna Maria de Groote, then probably to their elder son, Everhard Jabach (1658-1721);

acquired by Pierre Crozat, Paris, at an unknown date between 1695 and 1721, his sale, Paris, 10 April 1741, part of lot 5, catalogued by Pierre Jean Mariette, as Leonardo,

acquired by Jean-Baptiste-François Nourri;

an unidentified black chalk paraphe on the verso of the backing sheet;

Pierre Defer,

thence by inheritance to his son-in-law, Henri Dumesnil (L.739),

his sale, Paris, 10-12 May 1900, lot 255, as Leonardo;

Comtesse Martine Marie-Pol de Béhague;

Marquis Hubert de Ganay;

Marquis Jean Louis de Ganay,

his sale, Monaco, Sotheby's, 1 December 1989, lot 73, as Leonardo

Exhibited: Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Leonardo da Vinci, Mostra di disegni, manoscritti e documenti, 1952, no. 10;

Vinci, et al., La Raccolta Leonardesca della Contessa de Béhague, 1980-81;

Paris, Louvre, Leonard de Vinci: Dessins et manuscrits, 1989-1990, (catalogue by Françoise Viatte), no. 8

Literture: B. Degenhart, ‘Eine Gruppe von Gewandstudien des jungen Fra Bartolommeo’,Münchner Jahrbuch der Bildenden Kunst, vol. XI, 1934, p. 224, note 6 (as Fra Bartolommeo);

B. Berenson, The Drawings of the Florentine Painters, Chicago 1938, vol. I, p. 62, vol. II, no. 1071A, vol. III, fig. 525 (as Leonardo);

K. Clark, Leonardo da Vinci, Cambridge 1939, p. 12, under note 1 (as Leonardo);

B. Berenson, I Disegni dei Pittori Fiorentini, Milan 1961, vol. I, p. 102, vol. II, p. 211, no. 1071A, vol. III, fig. 445 (as Leonardo);

C. Ragghianti and G. D. Regoli, Disegni dal modello, Pisa 1975, p. 31, under note 10 (as Leonardo);

G. D. Regoli, ‘Il piegar de’panni’, Critica d’Arte, XXII, November-December 1976, pp. 47-48, under note 16 (mentions de Ganay group and attributes them to Leonardo);

A. Vezzosi and C. Pedretti, La Raccolta Leonardesca della Contessa de Béhague, Vinci 1980, p. 19, fig. 2 (as Leonardo);

A. Vezzosi and C. Pedretti, Leonardo’s Return to Vinci, The Countess of Béhague Collection, New York 1981, p. 21, fig. 2 (as Leonardo);

J. Snow-Smith, The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo da Vinci, Seattle 1982, pp. 53-54, fig. 51 (as Leonardo);

J. Cadogan, ‘Linen Drapery Studies by Verrocchio, Leonardo and Ghirlandaio’,Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 1983, vol. 46, p. 56, fig. 22, reproduced (as Leonardo);

Leonardo da Vinci, exhib. cat., London, South Bank Centre, 1989, p. 50, under cat. no. 3 (as Leonardo);

D. Scrase, ‘Paris and Lille, Leonardo: Italian Drawings’, The Burlington Magazine, February 1990, pp. 151-153 (as Leonardo);

K. Christiansen, ‘Leonardo drapery studies’, Burlington Magazine, August 1990, p. 572 (as Ghirlandaio);

D.A. Brown, Leonardo da Vinci: Origins of a Genius, London 1998 (discusses the group exhibited in 1989 and attributes it to Verrocchio and his Workshop);

P.C. Marani, Leonardo una carriera di pittore, Milan 1999 (as Verrocchio and his Workshop);

B. Py, Everhard Jabach, collectionneur (1618 – 1695), Paris 2001, pp. 20 and 274;

Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, exhib. cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003, pp. 116 and 119, under note 18;

Leonard de Vinci. Dessins et manuscrits, exhib. cat., Paris, Louvre, 2003, p. 56, under note 6, p. 57 and note 18 (as Leonardo);

C. Bambach, ‘Leonardo and drapery studies on ‘tela sottilissima de lino’’, Apollo Magazine, January 2004, p. 53, under note 30 (as Verrocchio);

B. Py, 'Everhard Jabach: Supplement of Identifiable Drawings from the 1695 Estate Inventory,' Master Drawings, vol. XLV, no. 1, 2007, p. 6, and p. 36 note 15;

A. Gauthier, ‘From Crozat to The Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes: The Origins of the Drawings Collection of the Marquis De Robien’, Master Drawings, vol. XLV, no. 1, 2007, p. 95;

L. Bicart-Sée, 'Some Archival References for Jean-Baptiste-François Nourri,' Master Drawings, vol. XLV, no. 1, 2007, p. 88;

G. Aubert, ‘From Crozat to the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes: The Origins of the Drawings Collection of the Marquis De Robien,’ Master Drawings, vol. XLV, no. 1, 2007, p. 95

Sixteen Drapery Studies from the Workshop of Verrocchio

These two remarkable drapery studies from the Barbara Piasecka Johnson Collection belong to a hugely important group of some 16 similarly drawn draperies on fine linen (‘tela sottilissima di lino’), which bear witness to the brilliance and originality of one of the most important of all Renaissance workshops, that of Andrea del Verrocchio (circa 1435-1488). There sculpture, painting and architecture came together in a unified artistic expression of monumentality, anticipating what Vasari would later describe as the nuova maniera. The achievements of Verrocchio’s workshop were essentially the product of his own incredible vision and talent, but also grew out of the innovative contributions of the various brilliant young artists in his bottega, most notably the young Leonardo da Vinci, who seems to have begun his apprenticeship between 1464 and 1469. Leonardo joined Verrocchio’s workshop more or less at the peak of the master’s career, when he was involved in major commissions for the Medici family, having rapidly taken over the mantle of the family’s favourite artist after the death of Donatello in 1466. Interestingly in the context of these drapery studies, Donatello was the first sculptor to experiment, already in the middle of the 15th century, with the use of actual fabric in casting the draperies of his figures, a famous example being the bronze of Judith and Holofernes, in Palazzo Vecchio, Florence.

This was a time of great dynamism and change, to which an innovative and restless intellect such as Verrocchio was perfectly suited. Vasari characterized Verrocchio not only as an artist interested in painting and sculpture, but also as a studioso who devoted time to ‘scienze’ and ‘geometria’,and a ‘musico perfettissimo’.1 His workshop was famous even beyond the borders of Tuscany as an educational centre for young artists, and in the mid-1470s no other workshop in Florence was producing comparable quantities of important paintings. Verrocchio’s bottegaembodied the highest formula of success for a Renaissance workshop, namely total command of different media.

The pivotal group of 16 drapery studies to which the Johnson drawings belong were produced in the febrile environment of Verrocchio’s studio during the 1470s, and constitute a unique contribution to the history of Italian Renaissance drawing. From this group, only the present two drawings remain in private hands; the others are all in European public collections.2 It was Giorgio Vasari, in the second (1568) edition of his Lives of the Artists, who first credited Leonardo da Vinci with having invented the highly experimental and original technique seen in these studies: drawn with the point of the brush in tempera, heightened with white body-colour, on finely woven linen prepared with a thin layer of grey-green, these remarkable drawings are at once both painterly and sculptural. If Vasari was correct in attributing the invention of this technique to Leonardo, the teenage prodigy clearly transformed both the technique and usage of drapery studies.

Vasari’s description of Leonardo’s drapery studies on tela di lino follows his mention of the young artist’s apprenticeship in the bottega of Verrocchio. Vasari writes that Leonardo ‘studiò assai in ritrar di natural’ and continues: ‘e qualche volta in far modegli di figure di terra; e adosso a quelle metteva cenci molli interrati, e poi con pazienza si metteva a ritrargli sopra a certe tele sottilissime di rensa o di panni lini adoperati, e gli lavorava di nero e bianco con la punta del pennello, che era cosa miracolosa, come ancora ne fa fede alcuni che ho di sua mano in sul nostro Libro de’ disegni’ (and sometimes in making models of figures in clay, over which he would lay soft pieces of cloth dipped in clay, and then set himself patiently to draw them on a certain kind of very fine Rheims cloth, or prepared linen: and he executed them in black and white with the point of the brush, so that it was a marvel, as some of them by his hand, which I have in our book of drawings, still bear witness).3 Although Vasari mentions that he himself owned some of these studies, none of the surviving examples are on his distinctive mounts, nor can any be associated with him by other means; yet clearly Vasari was not only familiar with these works, but also fascinated by the visual effect and remarkable impact of these revolutionary studies on linen.