Ashmolean's summer exhibition displays objects from ancient Egypt’s Amarna Period

Nose and lips of Akhenaten. Indurated limestone, 8.1 x 5.1 x 4.5 cm, about 1345-1335 B.C. © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

OXFORD.- Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter’s excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 was one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. The name of the ‘boy king’ is now synonymous with the glories of ancient Egypt and the spectacular contents of his tomb continue to enthral the public and scholars alike. The Ashmolean’s summer exhibition displays objects from ancient Egypt’s Amarna Period (about 1350–1330 BC) with material from the archives of Oxford’s Griffith Institute, celebrating its 75th year in 2014, to tell the story of the discovery of the tomb, its popular appeal, and to explore how modern Egyptologists continue to interpret the evidence.

Howard Carter (1874–1939) came to Egyptology through his skills as a draughtsman and artist, commissioned to copy hieroglyphic inscriptions and tomb paintings at the age of seventeen. By 1907 Carter had become an experienced archaeologist and was employed by George Herbert, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon (1866–1923), to lead his excavations of ancient tombs on the Theban west bank (opposite modern Luxor). In 1914 the opportunity to dig in the Valley of the Kings presented itself and both men jumped at the chance to search for one of the last royal tombs to be located, that of Tutankhamun.

Little was known about Tutankhamun when Carter and Carnarvon began their search. He appeared to have been a king of minor historical importance but ruled at a time when Egypt’s empire was at the height of its power and wealth, reaching from Sudan to Syria. Years of fruitless excavation followed and by 1922 Lord Carnarvon could no longer afford the costs and decided to terminate the work. Carter persuaded him to undertake one more season and within days of the renewed digging Carter wrote in his diary, on 5 November: “Discovered tomb under tomb of Ramses VI / Investigated same & found seals intact.”

The discovery caused a sensation. The Times of London was given exclusive access to the excavation and soon photographs of the tomb and its spectacular contents taken by the excavation’s photographer, Harry Burton, appeared around the world. Reporting on the story in February 1923, a New York Times correspondent wrote: “There is only one topic of conversation…One cannot escape the name of Tut-Ankh-Amen anywhere. It is shouted in the streets, whispered in the hotels, while the local shops advertise Tut-Ankh-Amen art, Tut-Ankh-Amen hats, Tut-Ankh-Amen curios, Tut-Ankh-Amen photographs. There is a Tut-Ankh-Amen dance tonight at which the piece is to be a Tut-Ankh-Amen rag.”

The public was in the grips of what became known as ‘Tutmania’. Throughout the 1920s, Egypt and its boy-king were celebrated in film, advertising, popular music, fashion, and design.

Discovering Tutankhamun brings together objects, photographs, and archive material from leading collections to tell the story of the search for the tomb, the painstaking recording of its contents, and the research that continues to illuminate Tutankhamun and his world. On display are Harry Burton’s iconic photographs, Carter’s hand-written diaries, and the sketches and records made in the tomb as it was cleared from 1922–32. Much of this material from the Tutankhamun archive in the University of Oxford’s Griffith Institute, has never before been exhibited in public. Other highlights include some of the finest art from the Amarna Period on loan from major international museums and from the Ashmolean’s own superb collections. Objects which illustrate the frenzied enthusiasm for ancient Egyptian art and culture, including 1920s jewellery and fashion, decorative arts, and vintage posters and advertisements, explore the 1920s ‘Tutmania’ and the fascination with Tutankhamun which endures today.

Professor Christopher Brown CBE, Director of the Ashmolean, says: “Discovering Tutankhamun tells a thrilling story of archaeological discovery and explores its impact on both scholarship and popular culture. The exhibition shows archival material which has never been seen in public before, with major loans from around the world, and provides the opportunity to re-examine pivotal moments in both ancient and modern history.”

Lord Carnarvon (middle) walking through the Valley of the Kings with the archaeologist Arthur Mace (left) and the chemist Alfred Lucas – both of whom worked on the conservation of objects from the tomb. © The Griffith Institute

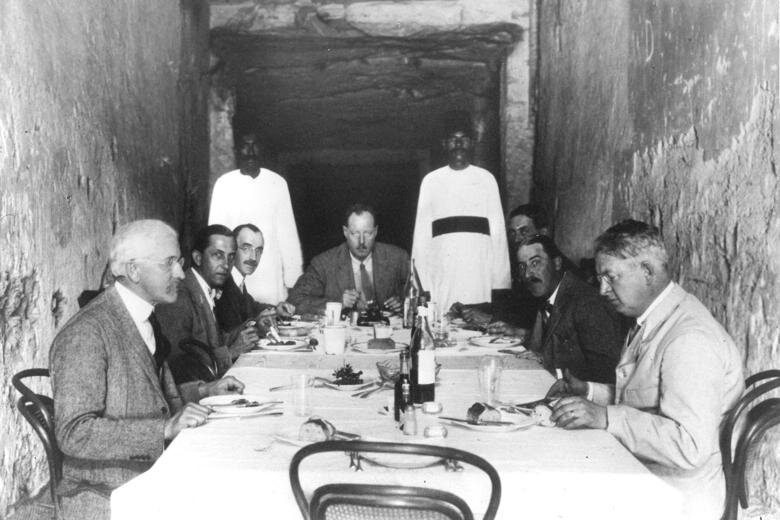

Left to right: James Henry Breasted, Harry Burton, Alfred Lucas, Arthur Callender, Arthur Mace, Howard Carter and Alan Gardiner eat lunch in the tomb of Ramesses XI in 1923. Photograph: Lord Carnarvon/Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Transporting objects from King Tutankhamun's tomb. Photograph: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

The first glimpse of Tutankhamun's tomb, Egypt, 1933-1934. Credit: The Print Collector / Heritage-Images

British Archaeologist Howard Carter In The Tomb Of King Tut. HARRY BURTON/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The mummy's curse … Archaeologist Howard Carter examining the coffin of Tutankhamen. Photograph: The Life Picture Collection/Getty

Tutankhamun's outermost coffin. Photo: Copyright Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

On the outside of the tomb, decorations depicted Tutankhamun as Osiris, while wall paintings, pictured, showed the king being embraced by the underworld god. It is believed that if Tutankhamun was shown to be this powerful god it would quash a religious revolution taking place in the 1320s BC. © Sandro Vanini/Corbis

Funerary treasure was found in his tomb, pictured, including an 24.2lb (10kg) solid gold death mask. However, the traditional heart scarab, used to show a body's worthiness for the afterlife, was missing. Religious texts claimed Osiris' heart was similarly removed by his brother Seth.

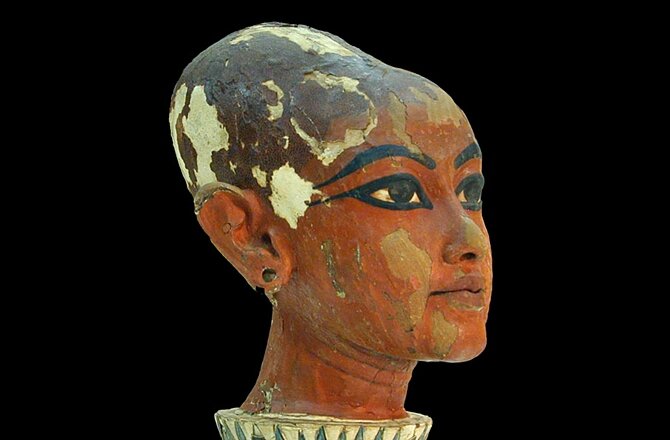

Limestone head of Tutankhamun from 1322 BC. Photo courtesy Metropolian Museum of Art, New York.

Queen Nefertiti offering a bouquet to Aten. Limestones fragment from a column, with traces of red and blue paint, from Tell el-Amarna, possibly from the Great Palace, 18th Dynasty, c 1345 BC © Ashmolean museum

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240315%2Fob_456a00_f12fdad5-0750-48f5-ae8f-7bd6836745f7.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F86%2F67%2F119589%2F129815803_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F40%2F54%2F119589%2F128112000_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F97%2F36%2F119589%2F128062654_o.png)