Islamic Art Week announced at Christie's London, to be held 21-24 April 2015

Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

LONDON.- From 21-24 April 2015, Christie’s two London salerooms will host a wealth of treasures from the Islamic and Indian worlds, showcasing the exquisite craftsmanship and diversity of works across the category. The week will begin with exceptional offerings from the Oriental Rugs and Carpets sale on 21 April and continues at King Street on 23 April with Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds and the South Kensington Arts & Textiles of the Islamic & Indian Worlds sale on 24 April, each presenting collectors with a unique opportunity to acquire these rare and magnificent works

Oriental Rugs and Carpets King Street, Tuesday, 21 April 2015

Christie’s sale of Oriental Rugs and Carpets will feature property from a number of exceptional collections from across the globe. Leading the sale is an important Mongol empire wool flatwoven carpet from the late 13th or first half 14th century, the only surviving carpet from the Mongol Empire and of significant importance in the understanding of Mongol Empire textiles (estimate: £500,000700,000). Further highlights of the sale include a particularly fine selection of Chinese carpets spanning three centuries, dating from the early 17th century to the early 20th century, two of which are from the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, as well as a seven-metre-long, late 16th century Cairene carpet from a private European collection (estimate: £60,000-80,000). The auction also features an array of beautiful silk rugs and carpets, including a large silk and metal-thread Koum Kapi carpet (estimate: £80,000-120,000).

An important Mongol empire wool flatwoven carpet, Central Asia or China, late 13th or first half 14th century. Estimate £500,000 – £700,000 ($742,000 - $1,038,800). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

Touches of wear, minor repair, slight loss to each selvage, original long striped kilim at the top end, secured along the lower end. Approximately 8ft.1in. x 2ft.8in. (246cm. x 81cm.)

Notes: This magnificent weaving is as mysterious as it is beautiful. It appears to be the sole surviving example of a Mongol wool tapestry-woven carpet and as such is of great importance in the canon of Mongol textiles and the history of carpet weaving.

The only visual record we have of carpets from the Mongol period is from their depiction in a series of Chinese paintings dating to the 13th century. The designs of the carpets in these paintings are clearly discernible and are characterised by strong yet elegant geometric patterns and a rich palette of red, blues, tans and white (M.S.Dimand and J.Mailey, Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1973, pp.21-25). These paintings provide a tantalizing glimpse of the designs of the carpets and context as to how they were used, but raise as many questions as they answer. In relation to the present lot the overall effect of the painted carpets is quite different and yet there are a number of shared design features, such as the palette, the outer stripe of discs or pearls and the use of lobed cloud band motifs (Volkmar Gantzhorn, The Christian Oriental Carpet, Cologne, 1991, pp.142-154).

We have a tantalizing glimpse of earlier simpler flatweave traditions in the form of a small group of 9th century flatwoven carpet fragments in the Al Sabah collection Kuwait (Friedrich Spuhler, Pre-Islamic Carpets and Textiles from Eastern Lands, London, 2014, pp.70-75 and pp.83-85). Many of them have ends that are finished with a series of stripes, in a very similar fashion to our carpet. Another very interesting feature is the closely related structure and selvage configuration, which is most clearly visible in a border fragment, inv. no. LNS 66 R (Friedrich Spuhler, ibid., cat.1.24, pp.84-84). The brindled wool Z2S warps are very closely related to the present carpet as is the plain multi-cord selvage, which shows signs of loss but appears to have 7 cords, to the 9 of our carpet. The palette, the geometric zigzag border and the suggestion of a pearl or disc minor stripe in one corner all suggest a shared heritage with our carpet. The border fragment was reportedly discovered in Northern Afghanistan. This led to Spuhler’s tentative attribution of Eastern Iran as the place of manufacture but it could just as easily have originated in Central Asia.

While the border design and structure relates to these earlier weavings, the field design appears to be from a very different tradition. It is much closer in both technique and aesthetic to the flower and bird silk tapestries or kesi of Central Asia and China. It has been suggested that the technique of those silk tapestries has its origins in wool tapestry weaving (J.E. Vollmer, Silk for Thrones and Altars, Chinese Costumes and Textiles, Paris, 2003, p.17). Silk kesi are thought to have originated with the Uyghurs, a Turkic people originating in Mongolia. After the fall of the Uyghur empire in the 9th century, we know from the account of an emissary in the Song Court, Hong Hao (1088-1155) in theSongmo jiwen (Records of the Pine Forests in the Plains), that Uyghurs were resettled in Northern Song dynasty territory in modern day Tianshui in Kansu province and were subsequently relocated to Yanjing, modern day Beijing, when the Jin Jurchens invaded. Hong Hao relates that some Uyghurs settled in the Kansu corridor whilst others went further to establish their own state, in Xinjiang. This narrative creates a fascinating picture of the dispersal of Uyghurs and their weaving skills across an arc from the Tarim basin to Beijing and corresponds with areas that we know produced kesi from at least the 10th century. We know that by the 13th century the Uyghurs were frequently employed by the Mongols in skilled administrative positions across the empire, and it cannot be coincidental that when Ögödei Khan was choosing locations for his resettlement of weavers he chose the Uyghur capital of Besh Baliq to be one of them.

The patterns and motifs of these Central Asian silk tapestries seem to have evolved through absorbing and synthesising the different artistic influences of nearly every major culture that moved along the great trading routes of the Silk Road. This transmission is well illustrated by an 11th-12th century silk kesi in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. No. 1988.100 (www.clevelandart.org/art/1988.100). The Cleveland kesi depicts a series of three horizontal bands or friezes depicting floral fields with real and mythical creatures divided by double borders. The patterns of these borders, a series of multi-coloured pearls abutting a stripe of bisected alternating lobed flower heads, appear as a prototype for the border of the present lot and show the influence of both Sogdiana and Tang China (James Watt and Anne Wardwell, When Silk Was Gold, Central Asian and Chinese Textiles, New York, 1997, pp.66-67). The designation of silk kesi to particular regions is however difficult. A tentative classification of kesi has been attempted on archaeological and stylistic grounds (James Watt and Anne Wardwell, ibid., p.53). The kesi that have been identified as Central Asian are characterised by their clever combination of naturalism and creative pattern-making, exuberant colours, and depiction of mythical or realistic animals and birds on floral grounds, all elements that can be seen in the design of the present lot.

One of the most closely related kesi designs to our kilim is found in two silk and metal-thread fragments, one in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv no. 66.174b, the other in the collection of the Textile Museum Washington D.C., inv. no. TM 51.61. Both have very similar drawing to the present lot and are executed in an interesting mixed technique. The way the treatment of the head of each bird, defined by an ovoid shape in contrasting colour, with a central beady ringed eye and clearly defined plumage is very similar to our carpet. The dynamic and boldly coloured outlines of the design are also closely related, as are the drawing of the voluptuous and elegantly swaying peonies and the omission of black from the composition. The Metropolitan Museum example is attributed to Song Dynasty China (960-1279) and catalogued as 11th-12th century. Intriguingly, the Asian Art department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has confirmed that their fragment has not been C14 dated. It would be very interesting to see if a C14 test would bring the dating much closer to that of our carpet, in the early Mongol period.

The Mongols first invaded North West China in the early 13th century and over a period of fifty years established the largest continuous empire ever to exist, spanning from Hungary to Korea. By 1260 the Mongol empire was loosely organized into four Khanates; the Yuan dynasty in China and Mongolia, the Golden Horde in Russia, the Chaghadai Khanate in Central Asia, and the Ilkhanid dynasty in Persia (Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, The Legacy of Genghis Khan, Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, New York, 2002, p.16). Whilst the ruthlessness and destruction of Genghis Khan (r.1206-1227) and his horde is well documented, what is often overlooked is the importance of the Mongols in the fostering of the arts and the development of trade throughout Eurasia almost immediately following the destruction. In spite of internal skirmishes between the different khanates, the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol Peace, ensured that foreign merchants and missionaries could travel from Europe to China in relative safety. It was this active encouragement of trade under the Mongols that led foreign merchants, such as Marco Polo, to seek their fortunes in the East by trading spices and textiles, leading to one of the largest expansions of trade in Eurasian history (James Watt and Anne Wardwell, ibid., pp.14-15).

Under Mongol rule, the status of artisans also rose. Genghis Khan freed craftsmen from corvée labour and relocated many of them from all over the empire to new areas. Genghis Khan’s son and successor, Ögödei Khan (r.1229-1241), established at least three settlements of textile workers in East and Central Asia, one in Xunmalin near present day Kalgan, another near Hongzhou in Inner Mongolia and a third in the Uyghur capital Besh Baliq, near modern-day Urumqi in the Tarim basin. Weavers were given special status due to the importance of textiles for trade, and the Muslim weavers from Persia were particularly prized for their ability to weave patterned silks and cloth of gold, nasij(James Watt and Anne Wardwell, ibid., p.14). The magnificent 14th century Ilkhanid silk and gold-thread tapestry roundel in the David Collection, Copenhagen, amply demonstrates why the Muslim weavers were so sought after (Kjeld von Folsach, Art from the World of Islam in The David Collection, Copenhagen, 2001, fig.642, pp.376-77 and Kjeld von Folsach, Pax Mongolica, ‘An Ilkhanid Tapestry-Woven Roundel’, Hali 85, pp.80-87).

The David Collection Ilkhanid silk and metal-thread tapestry makes a particularly interesting comparison to our carpet, due to it having been C14 dated to the first half of the 14th century. The bold colours, the floral and animal composition, and the incorporation of trefoil motifs in the David Collection roundel are all shared factors with our carpet. They are design features that have far more in common with the silk kesi of China and Central Asia than with known Islamic tapestry-woven textiles. However, stylistically the drawing of the elegant but highly stylized animals, birds and figures which relate closely to Ilkhanid metalwork iconography clearly identified as such by the inscriptions, the inclusion of cotton in the structure, the figurative composition and the legible Arabic inscription all suggest that it was woven within the Ilkhanid Empire centred on Iran.

In her article ‘Textiles and Patterns Across Asia in the Thirteenth Century’, Yolande Crowe considers the importance of looking at a range of crafts for evidence of more accurate attribution and addresses the correlation between ceramic and textile designs (Yolande Crowe, ‘Textiles and Patterns Across Asia in the Thirteenth Century, A Southern Song Tomb, Armenian Manuscripts and Mongol Tiles’, Carpets and Textiles in the Iranian World 1400-1700, Oxford and Genoa, 2010, pp.11-17). In this way the 14th century blue and white ceramics of the Yuan dynasty are of especial interest in the consideration of our carpet. The bold naturalistic motifs and carefully contrived pattern design of blue and white ceramics such as the magnificent fish jar sold in these Rooms, 11 July 2006, lot 111 are very similar to the drawing of the present carpet. In particular the furled lotus leaves and flowers and the waving grasses are reminiscent of the drawing of our carpet. This raises the possibility that the carpet may in fact have been woven in Yuan China.

The majority of this flatweave is woven in a standard kilim technique, with front and back being identical, the different colours of horizontal weft creating the blocks of colour. This is a very old technique. A kilim dated to the 4th /3rd century BC was sold in these Rooms, 5 April 2011, lot 100, contemporaneous with the kilims that were discovered in the frozen graves at Pazyryk. The example sold here in 2011 and the present kilim not only use the wefts to create the colour, but the wefts are also bent away from the straight horizontal to create curved lines which establish a much clearer graphic. The technique used in the present carpet has considerably more variety. As well as the curved wefts, in the narrow barber pole stripes a different technique is used, with the wefts of each alternating colour being carried over on the reverse until the next time that they are employed, making the reverse appear with loose lines of free travelling wefts like that of a verneh. Another interesting feature, which would have added a considerable amount of time to the weaving process, is the securing of the junctions where the different colours meet. Where there is a colour change each weft, rather than returning around the warp, is taken to the reverse and there looped around the weft from the adjoining colour, ensuring that there is as strong a join across breaks as there is in the solid blocks of colour. This additional technique makes the weaving considerably more stable, protecting the kilim from damage by preventing the weaving from opening up where colours change.

The carpet is in remarkable condition for its age with wonderfully rich and fresh colours. Despite some loss to one end, the design of the kilim reads as a complete weaving and it is tempting to argue that, if it was meant to be hung on the wall of a building tent or as a door flap, you would not expect it to be much longer than its current 246cm length. This theory would appear to be supported by the transition across the length of the design from the two doves sitting amongst the grasses and watery lotuses at the bottom of the kilim to the two large peonies above it reaching for the sky. This extremely important and beautiful weaving sheds new light on textiles of the Mongol Empire and is a new milestone in the history of carpet weaving.

A large Cairene Carpet, Egypt, second half 16th century. Estimate £60,000 – £80,000 ($89,040 - $118,720). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

Localised wear, a few small repairs, overall good condition;23ft.11in. x 13ft.6in. (727cm. x 410cm.)

Provenance: With the present owner since 1950. Property from a private Spanish collector

Notes: The large central floral medallion and rosette vinery border of this carpet reflect Sultan Selim's imposition of Ottoman stylistic principles on Egyptian carpets after he conquered Cairo in 1517. At that point, Turkish design elements including spring flowers, palmettes and leafy floral vinery in allover and medallion compositions, replace the geometric formalism of Mamluk carpets previously in production in Cairo. The emergence of this new style and its development has been the subject of considerable study. The best introduction remains, E. Kuhnel and L. Bellinger, Cairene Rugs and Those Technically Related, Washington D.C., 1957, pp.41-64. It is generally accepted today that the earliest examples of the group were made in Cairo, adapting the Ottoman design aesthetic with traditional Mamluk materials and techniques. The very earliest examples only used the three-colour Mamluk palette (see for example lot 99 in The Bernheimer Family Collection of Carpets, sold in these Rooms, 14th February 1996), but by the mid-16th century a number of other colours had been introduced. Notable among these were second tones of both blue and green used independently of each other, black, ivory and yellow, Walter Denny, "The Origin and Development of Ottoman Court Carpets", Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies II, London, 1986, pp.243-259.

The field design of the present carpet is typical of one sub-group where the medallion and spandrels are superimposed on an endless repeating field of palmettes and saz leaves. Serare Yetkin discusses this in her study on Turkish carpets (see S. Yetkin, Historical Turkish Carpets, Istanbul, 1981, pp.101-127; also W. Denny, 'The Origin and Development of Ottoman Court Carpets', Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies II, London, 1986, pp.243-259). The same clarity of drawing in both the border and field design of the present lot can be found on an extremely similar example offered in these Rooms by Davide Halevim, 14 February, 2001, lot 54.

This carpet is remarkably well preserved and it is a type which so very often only survives in an extensively worn or heavily restored condition. The typically soft wool is very susceptible to wear and has therefore been very substantially repiled in most examples. One typical example was sold by Christie's on the premises at Hackwood House (20-22 April 1998, lot 1118). Of similar palmette and saz leaf field design; that carpet had very little of the original red pile visible. A further comparable carpet is in the Textile Museum, Washington (Ernst Kühnel and Louisa Bellinger, Cairene Rugs and Others Technically Related, 15th Century-17th Century, Washington D.C., 1957, no.R 1.126, p.43 and pl.XXIII). Both the Hackwood and the Textile Museum carpets differ from the present lot in their inclusion of cintamani stripes interwoven amongst the Turkish flowers within the medallion and spandrels. A carpet with a closely related medallion and spandrel design to ours was formerly in the James F. Ballard Collection and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (M. S. Dimand, and J. Mailey, Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1973,fig.190, no.107).

Like their Mamluk counterparts, very few Ottoman Cairene rugs appear to have been depicted in Western paintings, perhaps because of their complex patterning and muted coloration. This is not to say that they weren't extremely popular with European collectors in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and many appear listed in European collection inventories of the period (Donald King and David Sylvester, The Eastern Carpet in the Western World from the 15th to the 17th Century, London, 1983, p.79).

A silk and metal-thread Koum Kapi carpet, Istanbul, Turkey, circa 1920. Estimate £80,000 – £120,000 ($118,720 - $178,080). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

Overall excellent condition; 12ft.11in. x 9ft.5in. (393cm. x 285cm.)

Notes: The Koum Kapi weavings get their name from the Koum Kapi (Sand Gate) district of Istanbul, the Armenian quarter, situated near to the Top Kapi area of the city. It was in these rather impoverishing streets that the Armenian workshops created arguably the most luxurious and beautiful silk carpets of the 20th century, inspired by the renewed interest in and publication of great classical weavings (Pamela Bensoussan, 'The Master Weavers of Istanbul', Hali 26, p.34). The present lot is a rare large format Koum Kapi and although unsigned its quality is unmistakable. Far fewer large format Koum Kapi carpets were woven than the small format rugs, and it is likely that almost all of these would have been woven as special commissions. In recent years two related large format Koum Kapi carpets have sold in these Rooms, 24 April 2012, lot 50 and 23 April 2013, lot 25. However, in both cases the field design was directly copying that of a published 16th century Safavid carpet; the design of the present carpet is quite different and more playful.

The field design of our carpet uses motifs taken from the two magnificent mid-16th century Herat spiral vine carpets in the Österreichisches Museum für angewante Kunst in Vienna, inv. no. T8376/1922KB and Or311/1891/1907, which were published by Sarre and Trenkwald in Altorientalische Teppiche, Vienna and Leipzig, 1926, pl. 9 and 10, the same design as lot 27 in the present sale, but has been reconfigured in the hands of the Koum Kapi weaver to create an original overall design. The motifs have been repeated and mirrored in a manner very similar to the designs of late 19th and early 20th century carpets woven in India and the weavers of which were looking to the same publications for design sources as the Koum Kapi weavers. Another interesting difference between the two large format carpets and our carpet is the length of the silk pile. The silk pile of the present carpet is not as closely clipped as the other two carpets which creates a greater contrast between the silk and metal-thread raised work.

Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds King Street, Thursday, 23 April 2015

Continuing this season’s Islamic Art Week, the King Street sale of Islamic and Indian Art presents an important astrolabe made in Iran in AH 1117/1705-06 AD (estimate: £150,000-250,000), demonstrating the confluence of science and beauty in the Islamic World, along with a striking celestial globe from Lahore, 1660 (estimate: £100,000150,000). Also featured is a beautifully rendered Ottoman gilt-copper Chamfron, possibly the most sculptural of all pieces of armour, providing both protection for the horse’s head and the opportunity for great decoration (estimate: £120,000180,000, illustrated centre page one). Furthermore, the sale includes a superb collection of rare Iznik dishes, led by an important ‘Damascus-Style’ Iznik dish which uses manganese glaze in combination with bright turquoise and emerald green to create the most outstanding of finishes (estimate: £70,000-100,000). Surviving examples of this type of Iznik are few and very rarely appear on the market, providing collectors the almost unique opportunity to acquire such an exquisite work of art.

Lot 77. A fine Safavid brass astrolabe, Tabriz, Iran, dated AH 1117-1705-06 AD. Estimate £150,000 – £250,000 ($222,600 - $371,000). Price realised GBP 170,500. Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

The brass mater with arabesque throne with upper trilobed palmette and suspension shackle, the reverse engraved with the date 1117 and with a dedication inscription in nasta'liq, the rim graduated [0-360° ] to 1° with larger markings every 5°, with five plates engraved on both sides each bearing stereographic projections for various latitudes each engraved with inscriptions in naskh and panels of elegant split palmettes, altitude circles every 6° and azimuth arcs every 10°, the reverse of one bearing a table of horizons, the rete with 19 named star pointers, the reverse of the mater with shadow square and projection for equal hours and a planetary table, the alidade with two holed sighting vanes and cusped cartouches containing scrolling vine issuing split palmettes at either end, the edge with long inscription cartouches with the name of the patron alternated with small quatrefoil cartouches containing flowers and split palmettes, the horse and pin possibly later; 5¾in. (14.6cm.) high overall; 3 3/8in. (8.5cm.) diam.

Engraved: In the upper trilobed palmette, wasa' kursihi al-samawat wa'l-ard, 'His throne extends over the heavens and earth [Qur'an II, sura al-baqara, parts of v.255]'

On the other side, hasb al-farmayesh-e 'alijanab-e moqaddas alqab-e sulalat al-sadat mirza 'ata allah al-husayni shaykh al-islam dar al-salatana tabriz-e bahjat angiz sar anjam yaft, 'It was completed on the order of His Exalted Excellency, the one with Holy Titles, of the lineage of Sayyids, Mirza 'Ata Allah al-Husayni, Shaykh al-Islam in the Dar al-Saltana, the splendour-inducing Tabriz'

Notes: The five plates are engraved with astrolabic markings for latitudes 28°, 30°, 31°, 32°, 34°, 35°, 36°, 37° and 38°. In this case 32° would serve Isfahan and 38° would be for Tabriz.

The compact size of this fine astrolabe suggests that it was designed for personal contemplation. The lightly rubbed edges show that this was manipulated by an erudite individual capable of making use of this complicated and very versatile instrument. An astrolabe of similar size dated to circa 1660 but with a later replaced rete was sold at Sotheby’s London, 6 October 2010, lot 150.

This astrolabe is very finely and accurately engraved. The proportions of the lines of latitude are very regular and consistent. The decoration of the scrolling vine is also exemplary displaying finely detailed split palmettes and scrolls of great fluidity. The large palmettes and cusped palmettes are reminiscent of contemporaneous Safavid manuscript illumination. A royal Safavid Qur’an written for Shah Sulayman Safavi (r.1666-94) copied in 1683 has an opening illuminated carpet bifolio displaying a similar combination of palmettes and split palmettes, sold in these Rooms, 17 April 2007, lot 100; and now in the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

The second numeral of the date on this astrolabe has been manipulated slightly. It appears as if the second number 1 has been partially erased in an attempt to transform it into a 0 to make the date read a hundred years earlier. In terms of both the style and the quality of engraving, our astrolabe is clearly early 18th century- and indeed of the highest quality. A number of astrolabes of similar style and date are known. One is in the Museum the History of Science in Oxford, signed by ‘Adb al-‘Ali and dated 1707-08. It has a cusped throne which is outlined by cusped palmettes which is very similar to our astrolabe, (inv.40330;http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/astrolabe/catalogue/frontReport/Astrolabe_ID=160.html#throne). A much larger astrolabe made as a showpiece for Sultan Husayn (r.1694-1722) dated 1712 AD in the British Museum has a very similar cusped throne with a border composed of split palmettes, (Inv. OA+.369, Sheila Canby, The Golden Age of Persian Art 1501-1722, London, 1999, pl.161, p.169). Another astrolabe dated to circa 1700 in the Museum of the History of Science collection signed by Khalil Muhammad ibn Hasan ‘Ali has a closely related nasta’liq inscription contained within a cusped cartouche which is closely related to our astrolabe, (inv. 35313, http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/astrolabe/catalogue/browseReport/Astrolabe_ID=133.html).

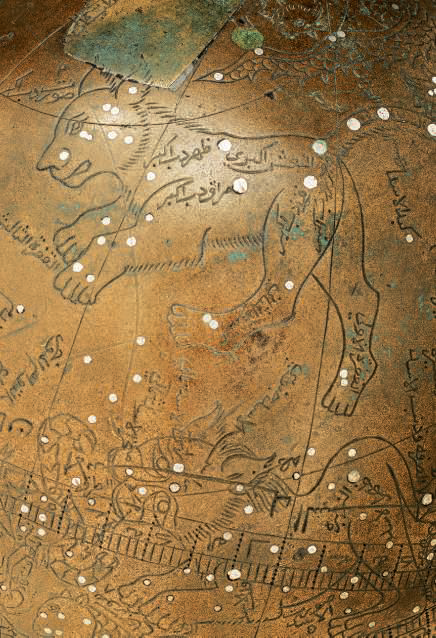

A celestial globe, attributed to Diya’ al-Din Muhammad bin Qa’im Muhammad bin Mulla Isa bin Shaykh Alladad Asturlabi Humayuni Lahuri, Lahore, circa 1660. Estimate £100,000 – £150,000 ($148,400 - $222,600). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

The seamless cast sphere engraved with graduations of the ecliptic numbered in 30° intervals, every degree indicated by a solid line and every fifth degree by a dotted line, celestial equator divided by single degrees with every fifth indicated by a dotted line, five degree intervals numbered continuously from vernal equinox, engraved with a full set of constellation figures, lower parts of Centaurus and Argo now lacking, the globe set with about 1018 silver stars in different sizes corresponding to six magnitudes of stars, each constellation labelled and given a number within either the northern or southern constellation, major stars also named, zodiac names engraved along ecliptic, a large rectangular plug at top through which is drilled the north celestial pole, smaller plugs of different alloy near Piscis Austrinus, small section by south polar area and a few stars now lacking; 5 1/8in. (13cm.) diam.

Notes: This celestial globe is attributable to Diya’ al-Din Muhammad bin Qa’im Muhammad bin Mulla Isa bin Shaykh Alladad Asturlabi Humayuni Lahuri. Diya’ al-Din was a member of a family who for four generations through the 16th and 17th centuries maintained a workshop at Lahore producing well-made scientific instruments, including planispheric astrolabes and celestial globes.

The family of metalworkers excelled in certain metallurgical techniques, in particular the production of hollow cast globes using the lost-wax, or cire perdue, method. The earliest extant instrument produced by the family was an astrolabe made in AH 975/1567-68 AD by the founder of the workshop, Shaykh Allahdad Asturlabi Humayuni Lahuri (formerly in the library of Nawab Sir Salar Jung Bahadur in Hyderabdad). The nisba Humayuni might suggest simply that he lived during the reign of Humayun or perhaps that he was an astrolabist active at his court. Twenty-one signed globes by this family of makers are known, of which Diya’ al-Din’s range in date from 1645 to 1680. One of his celestial globes (the only one which is not a seamless globe) bears an inscription stating that it was made at the order of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, indicating that his work was held in as high regard as that of the rest of his illustrious family (Private Collection, Paris; Emilie Savage-Smith, ‘Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their History, Construction, and Use’, Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, Number 46, Washington D.C., 1985, globe no.30, fig. 17, p.42).

Our globe is virtually identical to two examples signed by Diya’ al-Din and made in the same year, AH 1074/1663-64 AD. One of those, commonly referred to now as the ‘Barlow Globe’, is in the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh (inv.no.1890-331). The other is in the Museum of the History of Science, in Oxford (inv.no.57-84/25; Savage-Smith,op.cit., globes nos.27 and 28, pp.230-31). All three globes share the same engraving technique, design, precision and star placements – and are distinct from other examples known.

Whilst Diya’ al-Din’s prolific father Qa’im Muhammad worked within a limited framework, avoiding experimentation and giving scant attention to the decorative potential of the celestial figures he reproduced, his son Diya’ al-Din manipulated the traditional forms – paying more attention to decorative detailing such as variations in surface texture (Andrea P.A. Belloli, ‘The Constellation Figures on the Smithsonian Globe’, in Savage-Smith, op.cit., p.105). The iconography of figures such as Cassiopeia, Cepheus, Auriga, Boötes, Hercules, the head of Draco, Delphinus (with crown) and Argo are virtually the same on our globe and the Edinburgh and Oxford examples, all distinctive of Diya’ al-Din’s more ornamental and detailed style. The horse whip carried by Auriga, for instance, is transformed in Diya’ al-Din’s renditions to a staff issuing rows of leaf-like forms, as seen here. Similarly the Virgo of our globe is an elegant, slender creature who wears wide pearl bands at her cuffs and anklets at her feet. Her breasts are visible through her bodice and the upper sections of her wings are decorated with scalloped motifs. This is all extremely similar to the Oxford globe and completely different to the squatter simpler version depicted by Qa’im Muhammad (Belloli, op.cit., p.105). Diya’ al-Din’s Leo has more prominent, furry ears with broad hind legs and a head depicted in profile rather than turned to be seen full-face, as is more familiar from the work of his father, and contemporaneous manuscript illustrations.

The constellations on our globe, and the other related examples, are all presented in simple outline form, as is familiar in the illustrations to ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi’s (903-986 AD) Kitab suwar al-Kawakib (Book of the Constellations of the Fixed Stars), see for example a copy in Bodleian dated AH 400/1009-10 AD (Emmy Wellesz, An Islamic Book of Constellations, Oxford, 1965). The illustrations to the manuscript were clearly a source for the design of constellation images for globe makers, though as in illustrations to different copies of the text, the dress and artistic conventions found were clearly influenced by the trends of different locations and time periods. The style of dress worn by the human constellation figures here is clearly Mughal, and typical of that of western India in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The question naturally arises as to why our globe is not similarly inscribed with the name of the maker and the date of manufacture. In her discussion on a similar globe in the Smithsonian, unsigned but attributed by her to Qa’im Muhammad, Emilie Savage-Smith suggests that the reason for the lack of signature was a technical error. The maker placed the northern circle too far from the equator, probably then ceasing work altogether on the globe, as such an error would be impossible to correct. She suggests therefore that the maker never got around to adding his signature, as this would undoubtedly have been the last element to be engraved (Savage-Smith, op.cit., p..98). Our globe shows no technical inaccuracies. Indeed it is one of the finest preserved examples with respect to the quality of the inlay of the stars, which are precisely placed and indicated by magnitude. Most of the other known globes are signed towards the southern equatorial pole, and so it is probable that this important detail was lost with the damage that our globe sustained.

Emilie Savage-Smith writes of the Oxford globe that it has a long metal probe around which three pieces of paper, possibly amulets, were rolled and sewn together. These are too large to extract through the poles drilled for the axis, and rattle when the globe is shaken. She has suggested that perhaps the present globe had a similar arrangement, and that a later owner cut off the lower part in order to extract the contents.

We would like to thank Emilie Savage-Smith for her contribution to this catalogue note.

Lot 169. An Ottoman gilt-copper (tombak) chamfron , Turkey, 16th century. Estimate £120,000 – £180,000 ($178,080 - $267,120). Price realised GBP 158,500. Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

Of typical form, formed of a single sheet of metal, the surface shaped at the eyes and with pronounced medial ridge flaring at the bottom and terminating at the top in a rectangular cartouche filled with naskh on stippled ground, arabesque and floral cartouches around this, some issuing tulips, the sides of the long nose with panels filled with scrolling leafy vine, a series of holes for pins around the edges, minor areas of rubbing; 20¾in. (52.7cm.) long

Provenance: By repute formerly in the collection of Pidhirsti Castle,

Residence of John III Sobieski,

A Private European Collection

Engraved: In the roundels, al-sabr 'ibada, 'Patience is a[ form of] worship'

In the cartouche, al-sabr 'ibada wa'l-hamd 'ada (?), 'Patience is a [form of] worship and praise [of God] is a habit'

Notes: The chamfron is possibly the most sculptural of all pieces of armour. While the basic need to protect the horse’s head remained the same, the way of dividing the space allowed for huge variety of decoration. Widely varying forms were used from the 15th century through to the 17th century, where, particularly in Ottoman tombak versions, a great virtue was made of the play on different shapes (Fulya Bodur, Türk Maden Sanati, The Art of Turkish Metalworking, Istanbul, 1987, nos.A179, A180, A184, A185 and A186 for example).

The fashion for gilt copper, or tombak, developed in Ottoman Turkey in the 16th century. Whilst it was used primarily in the mosque and home for objects such as lamps, incense burners, candlesticks, and bowls, it also had an important function in a military context. A number of tombak helmets, chamfrons and shields are known. Because of the malleability of the copper, tombak armour would provide no effective defence in battle. It is likely therefore that the rich, lustrous pieces were created for parades and other ceremonial use, enhancing the pomp and colour of the Ottoman army.

James Allan acknowledges the possibility, however, that important Ottoman figures, such as sultans or viziers, might have used richly-decorated objects in battle as a symbol of their status (Yanni Petsopoulos (ed.), Tulips, Arabesques & Turbans. Decorative Arts from the Ottoman Empire, London, 1982, p. 42). The fact that there are a number oftombak pieces in the Karlsruher Turkenbeute from the collections of Baden-Baden suggests that in spite of its softness, the material must have been used at the siege of Vienna in 1683. It is clear that they were not the standard for the Ottoman army however. When used in battle, tombak armour was no doubt used only by the most important figures on the field. It is likely that our chamfron was taken at, or around, the time of the Siege of Vienna as part of the booty – the wealthy castle estates such as Pidhirsti Castle became rich depositories of the spoils of the siege.

Chamfrons of similar shape, although in steel rather than tombak, are in the Military Museum in Istanbul (for instance inv. nos. 208–14, 208–83 and 208–139; Tunay Guckiran, Askeri Müze, At Zirhlari Koleksiyonu, Istanbul, 2009).

Lot 175. An important ‘Damascus-Style’ Iznik pottery dish, attributable to ‘The Master of Hyacinths’, Ottoman Turkey, circa 1555. Estimate £70,000 – £100,000 ($103,880 - $148,400). Price realised GBP 422,500. Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

With cusped sloping rim on short foot, the white ground painted in cobalt-blue, turquoise, sage-green, manganese and grey with a bold floral spray composed of two large flowerheads issuing from a leafy frond, branches of hyacinth blossom and curved saz leaves in a near-symmetrical arrangement, the rim with a stylised 'wave and rock' design, exterior with bunches of tulips alternated with rosettes, repaired breaks; 14in. (35.6cm.) diam.

Provenance: Charles Gillet and thence by descent to present owner

Notes: Iznik ceramics with the rare colour combination seen here of blue, green, turquoise and manganese were originally thought to have been produced in Damascus. Many tiles were produced in the Ottoman Levant in the 16th century with the same repertoire of colours and with similar vegetal and floral designs. The Ottoman Sultan Sulayman the Magnificent (r.1520-66), commissioned the refurbishment of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The exterior walls were covered with tiles and the interior was decorated with hanging lamps. In the 19th century a large hanging lamp was found in Jerusalem. Now in the British Museum that lamp was signed by an artist called Musli and dated AH 956/1549-50 AD, (Inv. ME OA 1887.5-16.1; Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik, the Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, London, 1989, figs. 239 & 355). The lamp was also inscribed with verses in praise of a Sufi Saint, Eshrefzada Rumi and carried a reference to Lake Iznik confirming that it was produced there rather than in Damascus.

Julian Raby has suggested that the lamp signed by Musli and a number of other related vessels were produced by a workshop which he refers to as ‘one of the premier workshops in Iznik’, (Atasoy and

Raby, op.cit., p.135). Amongst the pieces produced by the workshop were a number of dishes closely related to our dish. These he attributes to an artist he termed ‘The Master of Hyacinths’. As defined by Raby the dishes produced by this artist illustrate a crucial transitional style in the designs of Iznik. The key elements include the use of the Chinese-inspired wave and rock design rim in conjunction with a typically Ottoman floral centre. Previously the wave and rock design had been limited to use on dishes imitating purely Chinese inspired designs. The idea of symmetrical floral sprays was also introduced. Our dish is evidence of this transition to a symmetrical design, as the design elements are balanced on both sides of the dish but stylised rosettes are still juxtaposed against leafy palmettes in what has not yet become an exact mirrored design. The framing of the floral design by curved braches of hyacinths found here is echoed on a dish attributed by Raby to the ‘Master of Hyacinths’, (Atasoy and Raby, op.cit., fig.256). The large overlapping rosette and palmette on the upper half of our dish is closely related to a dish with a similar design in the Gulbenkian collection which Raby also attributes to the artist and dates to circa 1555-60, (Atasoy and Raby, op.cit., fig.259, illustrated in colour, inv.no.823, published Maria Queiroz Ribeiro, Iznik Pottery, Lisbon, 1996, no.13, pp.116-17). A dish in the British Museum illustrates the next stage of this transitional period in which the decoration has become fully symmetrical but like our dish maintains the curved braches of hyacinths that frame the design, (Inv. G. 1983.21; Esin Atil, The Age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, New York, 1987, fig.185, p.262).

This dish represents a very short period of production in the history of Iznik before it emerges into the ‘Rhodian wares’ of the 1560’s and 70’s. The limited production period of these wares makes it exceptional to find a dish attributable to ‘The Master of Hyacinths’ still in private hands. Another ‘Damascus-Style’ Iznik dish was sold at Goya Subastas, Madrid, 19 December 2011, lot 245.

Arts & Textiles of the Islamic & Indian Worlds South Kensington, Friday, 24 April 2015

The South Kensington sale will conclude Islamic Art Week with a selection of more than 400 works of art. The sale includes a strong selection of Islamic manuscripts and works on paper, led by an Important Collection of Mediaeval Spanish and North African Manuscripts. A London Collection of Indian silver from the Raj is another highlight of the sale, as well as a fine 19th century, enamelled water pipe from Iran (estimate: £3,000-4,000), an Ottoman Kutahya pottery dish from the second half of the 18th century (estimate: £3,000-4,000) and an Ottoman silver pen case (divit) from the period of Mahmud I (estimate: £2,000-3,000). The sale also features 18th and 19th century Indian paintings, Central Asian textiles as well as ‘Orientalist’ works of art.

A fine enamelled water pipe (Qalyan), Qajar Iran, mid-19th century. Estimate £3,000 – £4,000 ($4,452 - $5,936). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

Of ovoid form, the polychrome enamel decoration consisting of oblique cartouches with floral garlands and rose flowers flanked by gilt scrollwork, two registers with portraits of youths interspersed within roundels with floral knotwork above and below; 9in. (23cm.) high

A fine Ottoman gemset parcel-gilt silver pen case (divit), with maker's mark of 'Muhammad', Turkey, period of Sultan Mahmud I (R.1730-1754 AD). Estimate £2,000 – £3,000 ($2,968 - $4,452). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2015

Of typical elongated from, of rectangular section with pronounced rounded terminals, one hinged, each engraved with scrolling floral vine, the barrel-shaped truncated octagonal inkwell with hinged cover set with green gem, secured with a small turning latch, the base and top engraved with similar floral designs, base of inkwell and pencase both marked with the tughra of Mahmud I, pencase stamped with maker's stamp in Arabic script reading "Amal-i Muhammad" within a lobed medallion; 11 ½in. ( 29.2cm.) long

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F78%2F119589%2F128999908_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F97%2F119589%2F128680994_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F22%2F37%2F119589%2F128680891_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F23%2F23%2F119589%2F127938278_o.jpg)