Recently discovered self-portrait headlines 'Leonardo da Vinci and the Idea of Beauty' at MFA Boston

Leonardo da Vinci, Head of a Young Woman (Study for the Angel in the "Virgin of the Rocks"), about 1483-85. Photo: Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

BOSTON, MASS.- For the first time in Boston, the “most beautiful drawing in the world” and a recently discovered self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) will be displayed. Presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from April 15—June 14, 2015, Leonardo da Vinci and the Idea of Beauty features a number of highly admired drawings by Leonardo. The exhibition, organized by the Muscarelle Museum of Art, explores the artist’s concept of ideal beauty through 30 drawings and manuscripts by Leonardo, Michelangelo and their followers. Because he left so few paintings, Leonardo’s drawings have been recognized for centuries as the deepest window into the workings of his mind. One drawing, Head of a Young Woman (about 1483–85), has been considered by some to be the “most beautiful drawing in the world,” bringing together his ideal of beauty and convincing naturalism to an astonishing degree. The Codex on the Flight of Birds (about 1505), an important loan from the Biblioteca Reale in Turin, features a newly discovered self-portrait. Identified five years ago, the partially hidden portrait depicts the artist at age 50. Works on view in the exhibition include a rich and varied selection of loans from Italy—primarily from the Uffizi Museum in Florence and the Biblioteca Reale. On view in the MFA’s Lois and Michael Torf Gallery, the exhibition also includes seven drawings by Michelangelo (1475–1564) and one from his studio, offering a unique opportunity to compare a series of these rivals’ drawings. Through the artists’ works, visitors can see how their ideals of beauty were often polarized, with Michelangelo more concerned with abstract, super-human ideals than the natural world that tantalized Leonardo.

“We are pleased to again work with the Muscarelle Museum of Art, a partnership which has brought our audiences face-to-face with rare and significant works by great Italian artists, loaned from Italy” said Malcolm Rogers, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA. “It is a privilege to present the public with such a special encounter with Leonardo, the greatest genius of his time.”

Leonardo’s works represent the culmination of the early Renaissance idea of beauty, and reflect his view that ideal beauty could be observed by study of the most perfect human features. He was the consummate “Renaissance Man,” the painter of the Mona Lisa as well as a scientist—designing flying machines and studying anatomy in intricate detail. Dedicated to Leonardo’s artistic style and philosophy, the exhibition is organized into sections focusing on the “Idea of Beauty”—including old age and youth; “Divine and Worldly Beauty;” and “Science and Anatomy.” Every decade in Leonardo’s career is represented, as well as his influence on his pupils—known as the Leonardeschi—and his greatest rival, Michelangelo.

“This exhibition presents a wonderful opportunity to spend time with a number of rarely displayed works, and to appreciate their timeless appeal,” said Helen Burnham, Pamela and Peter Voss Curator of Prints and Drawings at the MFA. “Leonardo’s drawings offer an intimate view into the workings of his extraordinary mind. They capture our attention with incomparable freshness and immediacy.”

From an early age, Leonardo had the habit of sketching people in profile, observing their faces as they assumed all varieties of appearance and expression. His interest in the craggy imperfections of old age and the loveliness of ideal youth is embodied in the celebrated red chalk drawing, An Old Man and a Youth Facing One Another (about 1500–1505). The young man may be based on Salai, a servant in the artist’s household who epitomized Leonardo’s notions of beauty. By contrast, the older man is a variation on an imagined warrior who appears often in the artist’s sketches. Working backward from old age to youth, the installation includes drawings by Leonardo and his assistants, as well as examples by Michelangelo and his studio. Two Drapery Studies executed at the very beginning of Leonardo’s career are a highlight of the section, and are among the artist’s greatest accomplishments.

Leonardo da Vinci, An Old Man and a Youth Facing One Another, about 1500–1505. Photo: Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Among a group of drawings depicting “Divine and Worldly Beauty” is Head of a Young Woman ( Study for the Angel in the “Virgin of the Rocks”) (about 1483–85). Said to be the most beautiful drawing in the world by art historian Sir Kenneth Clark, the work is a study for the oil painting known as the Virgin of the Rocks (in the Louvre Museum)—representing a universally admired example of Leonardo’s ideal of feminine beauty. Another drawing, A Young Woman (1495–1500), was also once considered to be among Leonardo’s finest works. The exhibition offers an opportunity to rediscover this enchanting drawing, which in 1880 was one of only two chosen for illustration in a seminal book on the artist. More than a century later it is relatively little known. The section on “Divine and Worldly Beauty” encompasses a number of Leonardo’s depictions of angels, which appear both divine and earthly in the works on view.

The final section, “Science and Anatomy,” includes the famed Codex on the Flight of Birds, which was recently found to contain a partially hidden self-portrait. The discovery was made in 2009 by a team of Italian journalists, imaging technicians and facial surgeons. The face, isolated from the writing, is convincingly similar to a drawing in the collection of the Biblioteca Reale, long believed to represent the artist in distinguished old age. However, much debate surrounds Leonardo studies, and the team’s conclusion has been doubted by a number of scholars. Aside from the self-portrait, the codex itself is an extraordinary compilation of Leonardo’s sketches and thoughts on flight. The topics covered in the work include the aerodynamics of a bird’s ascent and descent, the fluidity of air as it moves over a wing, and the difference between the center of gravity and the center of pressure on the avian form. Displayed in a sealed case and open to the newly discovered self-portrait, the entire codex includes numerous sketches and drawings.

Leonardo da Vinci, Codex on the Flight of Birds. On the right, an enhanced detail of the hidden self-portrait. Photo: Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Leonardo’s practice of drawing from life was on the cutting edge of scientific exploration in the Renaissance. Long fascinated by the “similarities of flight of birds, bats, fishes, animals, insects,” Leonardo’s scientific studies also include drawings of horses—animals Leonardo owned, rode, cared for, and sketched throughout his life—and insects. Two Studies of Insects (Study of a Beetle) (about 1480-1500) and Study of a Dragonfly (about 1505) were drawn at different points in the artist’s life, but were mounted together on a single sheet by a collector, perhaps in homage to the extraordinary powers of observation captured by the small studies. Two of the prior owners of this drawing—one, Sir Joshua Reynolds, a well-known British artist—left their marks (identifiable stamps) on the sheet, a tradition in the ownership of Old Master drawings.

Within the exhibition, drawings by Michelangelo and his studio—on loan from the Casa Buonarroti, his ancestral property in Florence—are displayed alongside Leonardo’s works. Both artists were fascinated by ideals of beauty, but looked to different sources for inspiration. Michelangelo more readily departed from nature and valued such incalculable qualities as gracefulness, power and drama as much as representation. Michelangelo’s practice of borrowing and exchanging (and improving) conventional forms of anatomy was an integral part of his approach, unlike Leonardo’s closer fidelity to the original natural source. Michelangelo’s forceful Study of a male nude for the figure of Naason’s Wife in the Sistine Chapel (1511) is an example of his relative freedom from anatomical exactness—a criterion that Leonardo never fully abandoned. The MFA previously displayed a number of the artist’s drawings in the exhibition Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane, Master Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti in 2013.

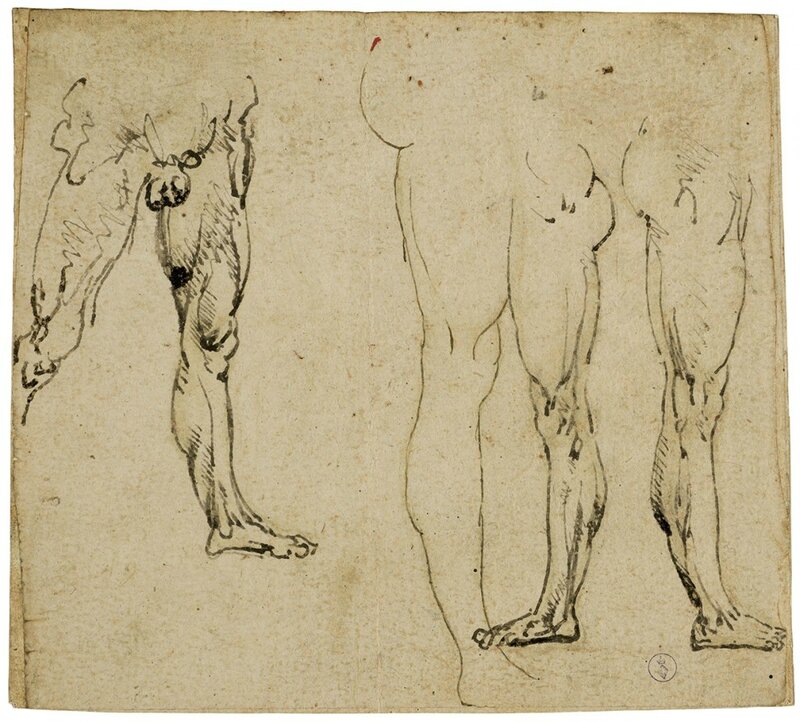

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for a male nude. Photo: Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Leonardeschi: Leonardo’s Pupils and Followers

No Leonardo exhibition is complete without including works by his close followers, which are sometimes so close in style and quality to his own that it is difficult to tell them apart. Leonardo encouraged pupils to copy his designs, and he would correct and even rework their drawings. A “Leonardesque” style emerged and was disseminated by his pupils as well as a large group of followers and imitators. Together they’re known as the Leonardeschi, and the exhibition includes an important selection of works associated with them. The drawing Head of an Old Man (about 1515) could be attributed to Leonardo or Cesare da Sesto—one of the more original members of Leonardo’s circle in Milan. This work may belong to a group by Leonardo depicting a similar-looking elderly man at different stages of maturity, or it may be by Cesare, who executed many drawings and paintings based on Leonardo’s designs.

This history explains some of the difficulty in differentiating Leonardo’s works from those of his followers. It also gives a sense of the group’s priorities—what they valued in the teachings of their master. Leonardo da Vinci and the Idea of Beauty invites visitors to try their hand at attribution, looking for characteristics such as Leonardo’s left-handedness in the works on view.

Leonardo da Vinci, Studies of Male Legs (recto). Photo: Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and a follower, Head of a Young Woman. Photo: Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F02%2F119589%2F129147865_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F12%2F119589%2F122078065_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F69%2F72%2F119589%2F120628255_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F47%2F119589%2F117900055_o.jpg)