The Morgan explores the unique role of drawing in portraiture in a new exhibition

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Portrait of the Artist’s Brother Endres, ca. 1518, Charcoal on paper, background heightened with white. Gift of Mrs. Alexander Perry Morgan in memory of Alexander Perry Morgan, 1973, The Morgan Library & Museum.

NEW YORK, NY.- Drawing is often seen as the most immediate of the fine arts, capturing a subject’s essence in quick, suggestive strokes of chalk, pencil, or ink. This can be particularly evident in portrait drawing where the dynamism of the medium allows for the recording of a likeness in the here and now, while simultaneously offering clues into the relationship between artist and sitter.

In a new exhibition titled Life Lines: Portrait Drawings from Dürer to Picasso, the Morgan Library & Museum takes visitors on a fascinating exploration of the genre. Spanning five centuries and including more than fifty works—from Dürer’s moving sketch of his brother Endres to Picasso’s highly expressive portrait of the actress Marie Derval—the show features treasures from the Morgan’s collection as well as a number of notable drawings from private holdings. The exhibition is on view through September 8.

“Life Lines is aptly named as no medium quite captures a person or the connection between artist and sitter like drawing,” said Peggy Fogelman, acting director of the Morgan. “Whether a dashedoff sketch of family life by Rembrandt or a preparatory study for a famous marble bust by Bernini, each work in this revealing exhibition is a window into a personal world.”

The drawings in the exhibition are organized thematically into four sections: Self-Portraits; Family and Friends; Formal Portraits; and a final grouping, entitled Portraits?, that explores the boundaries of this type of work. The pieces range from early studies for paintings and sculptures to highly-finished drawings that stand alone as works in their own right. What all of them share, however, is the image of a likeness of someone worth remembering, bearing testimony to the deeply human sentiment to leave a mark.

I. Self-Portraits

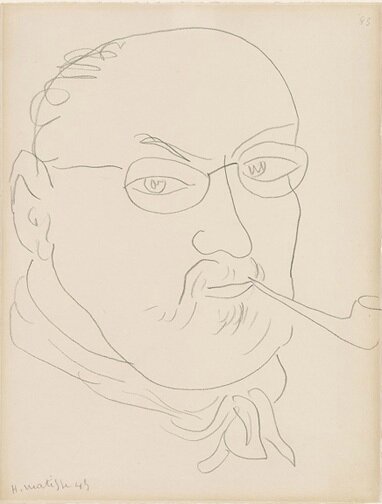

“Selfies” are hardly a new phenomenon. Many artists have recorded their own likeness over the past five hundred years, and examples in this section range from Palma il Giovane (1544-1628) to Henri Matisse (18691954). Some artists like to faithfully record their image looking into a mirror. Others embed their likeness in a decorative or narrative context, often showing themselves as artists.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Self-Portrait, ca. 1790, Graphite on blue writing paper, Purchased on the Fellows Fund, 1955, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Self-Portrait, 1945, Graphite on paper, Thaw Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum. ©2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Italian Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674-1755), for example, portrays himself in fanciful costume, while holding a caricature of his likeness wearing a cape. This humorous work is a self-portrait within a self-portrait, demonstrating the whimsy of an artist best known for his ironic sketches of both Rome’s citizenry as well as notable visitors to the ancient city. Ghezzi’s two depictions of himself seem to stand facing one another, one pointing his finger at the other, as if in conversation.

Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674-1755), Self- Portrait, ca. 1730, Pen and brown ink over traces of graphite on paper. Gift of János Scholz, 1985, The Morgan Library & Museum.

II. Family and Friends

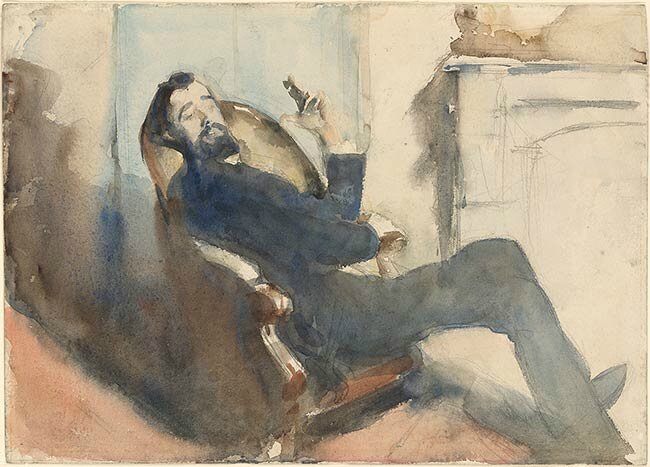

Many of the drawings presented of family and friends are not given the trappings of formal portraiture. They record the people closest to the artists: their children, spouse, siblings, and friends. Some of these drawings, such as Rembrandt’s (1606-1669) sketch of his wife Saskia asleep, are particularly intimate.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606-1669), Two Studies of Saskia Asleep, ca. 1635-37, Pen and brown ink and wash on paper. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Gaetano Gandolfi (1734-1802), Portrait of the Artist’s Daughter Marta, ca. 1776, Red and black chalk on paper, Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1986, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), Portrait of Jane Morris (née Burden), 1860, Graphite on paper, Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), Portrait of Paul-César Helleu, ca. 1882- 85, Watercolor over graphite on paper, Gift of Rose Pitman Hughes and J. Lawrence Hughes in memory of Junius and Louise Morgan, 2005, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) drawing of his younger brother Endres can be identified thanks to a portrait of him at the Albertina in Vienna. While that portrait, dated and inscribed, shows Endres on his thirtieth birthday, the drawing in Life Lines appears to be slightly later. More stylized than the earlier version, it shows Endres clad in a fur-trimmed coat and wearing his beret boldly aslant.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Portrait of the Artist’s Brother Endres, ca. 1518, Charcoal on paper, background heightened with white. Gift of Mrs. Alexander Perry Morgan in memory of Alexander Perry Morgan, 1973, The Morgan Library & Museum.

III. Formal Portraits

The largest group of drawings is devoted to more formal portraits, many of which would have been commissioned from the artists. A sketch of Cardinal Scipione Borghese by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), for example, is preparatory for a marble bust, while a portrait of Anna van Thielen and her daughter by Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641) serves as a study for a painting. Van Thielen was the wife of the Antwerp painter Theodoor Rombouts (1597-1637).

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), Portrait of Sisinio Poli, 1638, Black, red, and white chalk on paper, Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), Portrait of Martha Hess, 1778-79, Black chalk heightened with white on paper, Gift of Mrs. W. Murray Crane, 1954, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), Portrait of Adolphe-Marcellin Defresne, 1825, Graphite on paper, Thaw Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Joseph Ducreux (1735-1802), Portrait of a Gentleman (Toussaint Louverture?), ca. 1802, Black, brown, and white chalk on paper, Estate of Mrs. Vincent Astor, 2012, The Morgan Library & Museum.

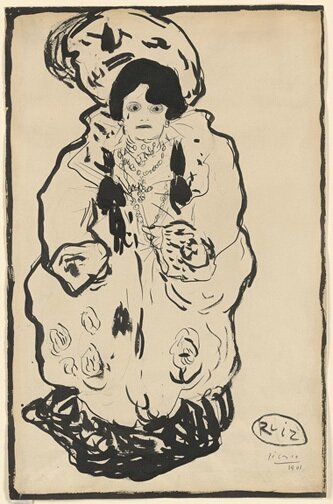

Among the many extraordinary works with a more finished polish is an early drawing by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) depicting Marie Derval, a popular actress in Paris at the turn of the century. The energetic contour of the figure and her frightening stare lend the portrait an expressionist vigor reminiscent of the work of Picasso’s contemporary Edvard Munch (1863-1944).

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Portrait of Marie Derval, 1901, Pen and brush and black ink over graphite on paper. Thaw Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum. © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

IV. Portraits?

Some drawings defy the conventional notion of portraiture. Though resembling portraits in one way or another, they raise the question of what actually constitutes such a work. This section invites visitors to draw their own conclusions and reflect upon traditional boundaries of the genre.

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Study of a Lady, ca. 1785-90, Black and white chalk on paper, Purchase, 1943, The Morgan Library & Museum.

The sitter posing for Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), for example, is identified in the inscription. The artist made this impressive life study in preparation for one of several paintings based on Laurence Sterne’s 1768 novel, A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy by Mr. Yorick. In the episode sketched out, the protagonist meets an old man weeping at the death of his donkey. The inscription reads: “Portrait of / John Stavely / who came from Hert- / fordshire with Mr. French / & sat to Mr. Wright in the character of the old man & his ass in the / Sentimental Journey”. But does this identifying text make the drawing a portrait?

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), Portrait of John Stavely, ca. 1775, Pen and black ink over graphite on paper, Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

And what about Hendrik Goltzius’s (1558-1617) staggering Young Man Holding a Skull and a Tulip, executed in 1614? A life-size “fantasy portrait,” it is a virtuoso finale to the artist’s series of pen-and-ink drawings in the style of engravings. The Latin inscription “Quis evadet? / Nemo” (“Who escapes? / No one”) and the symbols of the hourglass, skull, and tulip serve as a reminder of mortality and the transience of existence. Although the distinctive face was probably based on a young man whom Goltzius knew, the purpose of the drawing seems more to impart the foreboding message than to capture the likeness of the youth.

Hendrik Goltzius (1558-1617), Young Man Holding a Skull and a Tulip, 1614, Pen and brown ink on paper. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F25%2F77%2F119589%2F129711337_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F17%2F119589%2F127198849_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F17%2F87%2F119589%2F122324247_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F00%2F55%2F119589%2F120707983_o.jpg)