Four Lucio Fontana at Christie's Post War and Contemporary Art Evening Auction, 30 June 2015

Lot 21. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale, Attese; signed, titled and inscribed ‘l. Fontana “Concetto Spaziale” ATTESE Nel 1906 quando arrivai a Milano c’erani i tram a cavalli’ (on the reverse); waterpaint on canvas; 36 ¾ x 28 7/8in. (93.2 x 73.5cm). Executed in 1967. Estimate: £8,000,000 – 12,000,000 ($12,672,000 - $19,008,000). Price realised GBP 3,274,500. Photo: Christie's Image Ltd 2015.

Provenance: E. Muggia Collection, Milan.

Anon. sale, Sotheby’s London, 9 December 1999, lot 34.

Private Collection, Italy.

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Literature: G. Ballo, Lucio Fontana: Idea per un ritratto, Turin 1970, no. 266, p. 259 (illustrated, p. 226).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnements spatiaux, vol. II, Brussels 1974, no. 67 T 107, p. 162 (illustrated, p. 196).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo generale, vol. II, Milan 1986, no. 67 T 107 (illustrated, p. 673).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. II, Milan 2006, no. 67 T 107 (illustrated, p. 867).

Exhibited: Varese, Villa Mirabello, Lucio Fontana. Mostra antologica, 1985, no. 84, p. 149 (incorrectly illustrated, p. 132).

Notes: ‘[T]here are people who recognise that the hole, in the sense of the void, nothing, made by subtraction from the canvas, can say a great deal’ (L. Fontana (1966), quoted in A. White, Lucio Fontana: Between Utopia and Kitsch, Cambridge, MA. and London 2011, p. 256).

Stretching up and down most of this sumptuously-red canvas are three elegant, near parallel slashes. Created by Lucio Fontana in 1967, when he was at the peak of his fame and international recognition, Concetto spaziale, Attese is one of the artist’s iconic - and paradoxically iconoclastic - series of Tagli, or ‘Cuts.’ Only a year before he made this work, Fontana had exhibited an entire room filled with ‘Tagli’ of a vast scale, all on white, at the Venice Biennale. Here, rather than the glacial cool of that white room, Fontana has used a pulsing, vibrant red that recalls speeding Ferraris, blood, fire and heat.

In Concetto spaziale, Attese, the artist has taken his monochrome canvas - prepared so that the red waterpaint has been applied evenly to the point that the artist’s hand appears almost absent - and has rent it open, slashing it with three calligraphic, almost straight lines. These appear close together, creating a vertical rhythm that even hints tantalisingly at figuration: if these were brushstrokes, they could represent a column, or perhaps elongated human figures like those of Alberto Giacometti. Similarly, this focus on the upright echoes the abstract works of Fontana’s contemporaries across the Atlantic, Clyfford Still and Barnett Newman. Yet in Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, Attese, these are not brushstrokes: they are anti-brushstrokes, subtractions rather than additions. They are openings, they are space. Fontana, as sculptor, rather than painter, has penetrated the canvas, thus revealing its three-dimensionality. And at the same time, he has carved, using as his material not the support, but the void itself.

Clyfford Still, 1947-R-no.1, 1947. © DACS, 2015.

Fontana had first deliberately ruptured the picture surface in works he created as early as the late 1940s, initially piercing paper supports. Within a short time, he moved onto canvases, and began to explore a variety of means of puncturing the two-dimensional arena traditionally reserved for illusions of space, rather than inclusions of space. As he explained, around the time that Concetto spaziale, Attese was created: ‘I make a hole in the canvas in order to leave behind the old pictorial formulae, the painting and the traditional view of art and I escape symbolically, but also materially, from the prison of the flat surface’ (L. Fontana, quoted in T. Trini, ‘The last interview given by Fontana’, in W. Beeren & N. Serota (ed.), Lucio Fontana, exh.cat., Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1987, p. 34).

The development of the ‘hole’, and later, the ‘cut’, therefore chimed perfectly with the Spatial Art that Fontana had advocated: he was showing the redundancy of the old means of creating pictures, while also introducing a new path. He was also highlighting the entire suspension of disbelief involved in figurative picture making, and banishing it in a stroke. He brought instead his sculptor’s sensibility to pictures, highlighting their three-dimensionality and thus creating an intriguing precursor to the Minimalism which would flourish more than a decade after this epiphany. At the same time, Fontana was enshrining space itself within the work, introducing eloquent voids.

In the earlier Buchi, these voids took the form of punctures that resembled constellations of tiny stabs, evolving into large wound-like tears in his Olii and the celebrated Fine di Dio series. However, in the late 1950s, Fontana also introduced the slash as a means of opening up the canvas. In doing so, he created a very different aesthetic from the variegated punctures of the Buchi and, in particular, the Barocchi, works from the mid-1950s which featured holes, impasto and also sometimes other materials embedded within the surface. Looking at Concetto spaziale, Attese in relation to those works, the contrast could not be more clear: Fontana has voided the canvas of that materiality, replacing it with a new elegant concision. As he himself explained,’With the slash I invented a formula that I don’t think I can perfect. I managed with this formula to give the spectator an impression of spatial calm, of cosmic rigour, of serenity in infinity’ (L. Fontana, quoted in E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Vol. I, Milan 2006, p. 105).

This serenity is made all the more potent in Concetto spaziale, Attese by the sheer uniformity of the monochrome red canvas which has been punctured with the three cuts. Fontana was an older statesman, a pioneer who worked in parallel with younger artists such as Piero Manzoni and Yves Klein. This was the age of the monochrome and of theAchrome, and Fontana embraced it wholeheartedly. He used the monochrome as a base for his cuts, insisting upon the viewer’s attention upon the openings, emphasising that it was the immaterial, invading the fabric of the canvas, rather than the material itself, which was key. The rich red of Concetto spaziale, Attese is all the more intriguing as a colour choice, as it recalls blood and fire, elements that speak of life and flesh as well as destruction. There is a heat to this work that is sensual, all the more so because of the slits that punctuate its surface, at odds with the coolness of International Klein Blue.

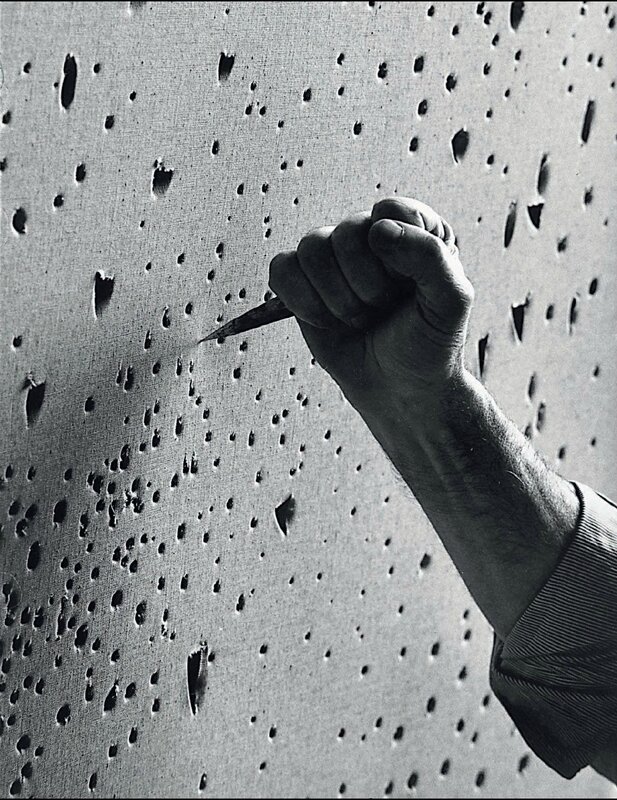

Fontana used several techniques in order to highlight his cuts and make them more dramatic, drawing the viewer’s attention. He developed slashes which were themselves almost balletic, or calligraphic, as is the case in Concetto spaziale, Attese. At the same time, he would usually back the cuts with black tape in order to emphasise the sense of infinite depth and space they invoked. As had been the case with his earlier Concetti spaziali, Fontana innovated and improved upon a number of techniques in order to capture the aesthetic he sought. Fontana was aware that his slashed monochromes gave the illusion of being easy to create, but explained that there was an almost ritualistic process behind them. They were the result of contemplation and consideration, as well as the blade-wielding skill at the end. Looking at the rhythmic progression of slashes in Concetto spaziale, Attese, this becomes clear. One can well understand the truth behind his explanation to the photographer Ugo Mulas, who had wanted to take pictures of him in action:

‘I need a lot of concentration. That is to say, I don’t come into the studio, take of my jacket, and - snap! - make three or four cuts. No, sometimes I leave the canvas hanging there for weeks before being sure what I’m going to do with it, and only when I feel sure do I start, and it’s rare for me to spoil a canvas; I have to feel in really good shape to do these things’ (L. Fontana, quoted by U. Mulas, in G. Celant, Lucio Fontana: Ambienti Spaziali: Architecture Art Environments, exh. cat., Gagosian Gallery, New York, 2012, p. 318).

Lot 57. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale, Attese; signed, titled and inscribed ‘l. Fontana “Concetto Spaziale” “ATTESE” mi fa proprio male i reni… meglio riposare…’(on the reverse); waterpaint on canvas; 25 5/8 x 32 1/8in. (65 x 81.3cm.). Executed in 1965. Estimate: £800,000 – 1,200,000 ($1,267,200 - $1,900,800). Price realised GBP 1,706,500. Photo: Christie's Image Ltd 2015.

Provenance: Galleria Rotta, Genova .

Acquired from the above by the present owner circa 1970.

PROPERTY FROM A DISTINGUISHED EUROPEAN COLLECTION

Lietrature: E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnements spatiaux, vol. II, Brussels 1974, no. 65 T 63, p. 162 (illustrated, p. 163).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo Generale, vol. II, Milan 1986, no. 65 T 63 (illustrated, p. 569).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. II, Milan 2006, no. 65 T 63 (illustrated, p. 758).

Notes: We refuse to believe that science and art are two separate things, in other words, that the gestures made by one of the two activities do not also belong to the other. Artists anticipate scientific gestures, scientific gestures always lead to artistic gestures’ (Second Manifesto of Spatialism, 1948-1949, reproduced in R. Miracco, Lucio Fontana: At the Roots of Spatialism, exh. cat., Estorick Collection of Modern Art, London, 2007, p. 37).

‘What we want to do is to unchain art from matter, to unchain the sense of the eternal from the preoccupation with the immortal. And we don’t care if a gesture, once performed, lives a moment or a millennium, since we are truly convinced that once performed it is eternal’ (L. Fontana, ‘First Spatialist Manifesto’, 1947, reproduced in E. Crispolti et al. (eds.), Lucio Fontana, Milan 1998, pp. 117-18).

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow, 1936. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Digital Image: © The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Erupting forth in a burst of radiant yellow, like the glowing rays of the burning sun, Concetto spaziale, Attese is a glorious example of Lucio Fontana’s iconic tagli, or cuts, which have come to embody the very essence of the artist’s Spatialist theories. Slashed from the very top of the canvas to the bottom with sweeping, almost balletic gestures, the pure field of vivid yellow is ruptured by seven pristine cuts, each incision following the cadence of the artist’s hand as it scores the surface of the painting. One of only two works conceived by Fontana to unite seven immaculate cuts on a dazzling yellow canvas, Concetto spaziale, Attese has been part of the same private collection since its execution in 1965. Created mid-way through the most astounding decade of space travel in man’s history, with its sun-drenched palette Concetto spaziale, Attese pays tribute to the galactic accomplishments so admired by Fontana. From the first human voyage into space in 1961, to the moon landing in 1969, achieved one year after the artist’s death, in the same way that pioneering astronauts probed the far flung corners of the cosmos throughout the 1960s, so too did Fontana’s pioneering slashing gestures seek to access an unknown dimension beyond the surface of the canvas. Invoking the life-giving force at the heart of the solar-system, in Concetto spaziale, Attese the conceptual grounding of the tagli is imbued with a new level of painterly poeticism, a programmatic attempt to give substance to the mystical and immaterial quality of sunlight as it penetrates the uncharted depths of the universe, each cut prised open to reveal the infinite void which lies beyond. Evocative of solar eclipse – that unearthly, disquieting phenomenon – the work embodies the sense of awe and wonder that accompanied a decade of galactic triumphs.

Concetto spaziale, Attese occupies a significant place within the new artistic paradigm proposed by Fontana’s Spatialist theories. As an ode to the sun – the central life-giving source of light, energy and matter – the work invokes the magic and mysticism of the spatial exchange between the material object and the immaterial quality of light through its brilliant yellow palette. Unifying the physical properties of painting with the concept of an, as yet, unexplored dimension, the earthbound materiality of the work is infused with a sense of colour, light and energy, through the immaterial realm liberated beyond the surface of the canvas. Just as the sun itself fuses light and physical substance, so too does the work combine a sense of the intangible with the properties of solid matter. Concetto spaziale, Attese further probes Fontana’s intense fascination with sunlight that the artist cultivated in the luminous oil and metal works produced in response to his sojourns in Venice and New York in 1961. Though enraptured by the golden symbolism of Byzantium and St. Mark’s, as well as the glimmering reflective surfaces of Venetian architecture, it was not until arriving in New York that Fontana experienced his true epiphany. ‘New York is a city made of glass colossi on which the Sun beats down, causing torrents of light’ (L. Fontana, quoted in G. Livi, ‘Incontro con Lucio Fontana’, in Vanità, vol. VI, no. 13, Autumn 1962, p. 52). Overwhelmed by the city’s futuristic dynamism, Fontana recounted with great excitement, ‘yesterday I went to the top floor of the most famous of the skyscrapers … the one made of bronze and gilded glass … It seemed to contain the Sun’ (L. Fontana, quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, ‘Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York’ in Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 2006, p. 42).

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of St. Teresa, (detail). Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome. Digital Image: © Alinari / Bridgeman Images.

Responding to the advent of space travel and the extraordinary scientific advances that shook the twentieth-century, Fontana sought transcendent new directions within his practice that could adequately express the revolutionary new ways in which mankind had come to perceive their place in the universe. Fascinated by the astronomical discoveries that had shown the uncharted territories of the cosmos to be potentially infinite, Fontana felt it essential to find an art that could explore these limitless possibilities, writing in 1948, ‘We refuse to believe that science and art are two separate things, in other words, that the gestures made by one of the two activities do not also belong to the other. Artists anticipate scientific gestures, scientific gestures always lead to artistic gestures’ (Second Manifesto of Spatialism, 1948-1949, reproduced in R. Miracco, Lucio Fontana: At the Roots of Spatialism, exh. cat., Estorick Collection of Modern Art, London, 2007, p. 37). Published in 1947 by Fontana and other avant-garde artists in Buenos Aires, theManifesto Blanco outlined a new ideology known as Spatialism, which called for ‘the development of an art based on the unity of time and space’ (Manifesto Blanco, 1946, reproduced in R. Fuchs, Lucio Fontana: La cultura dell’occhio,exh. cat., Castello di Rivoli, Rivoli, 1986, p. 80). Piercing the canvas, initially with his series of bucchi, or holes, and subsequently through his tagli, Fontana discovered an elegant solution to his conceptual aims, creating an object at once painting and sculpture, which could exist both in material space, while denoting the immateriality of the mysterious void. As the artist explained, ‘the discovery of the cosmos is a new dimension, it is infinity, so I make a hole in this canvas, which was at the basis of all the arts, and I have created an infinite dimension… the idea is precisely that, it is a new dimension corresponding to the cosmos… Einstein’s discovery of the cosmos is the infinite dimension, without end… I make holes, infinity passes through them, light passes through them, there is no need to paint’ (L. Fontana, quoted in E. Crispolti, ‘Spatialism and Informel. The Fifties’, in Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Milan, 1998, p. 146).

Fontana’s desire to create an art that remained relevant to the era of scientific discoveries in which he lived is evident in the gestures with which he created Concetto spaziale, Attese. These gestures capture the very essence of movement, the wake left by parting particles, the ripples in space and time. With each iconoclastic action the artist captured a moment in eternity, transforming the two-dimensions of painting into an infinity of space. As he once expounded, ‘what we want to do is to unchain art from matter, to unchain the sense of the eternal from the preoccupation with the immortal. And we don’t care if a gesture, once performed, lives a moment or a millennium, since we are truly convinced that once performed it is eternal’ (L. Fontana, ‘First Spatialist Manifesto’, 1947, reproduced in E. Crispolti et al. (eds.), Lucio Fontana, Milan 1998, pp. 117-18). The spiritual significance of the number seven resonates within this work. In the velvety blackness of each slit the profundity of man’s extraordinary galactic steps resounds with the echo of Western civilisation encapsulated by the apocryphal tale of the seven days of creation. Intimating a mysterious ‘fourth dimension’, Fontana’s work sought to engage with a higher plane. He wrote, ‘It is eternal insofar as the gesture, like any other perfect gesture, continues to exist in the spirit of man as a perpetuated race. Likewise, paganism, Christianity and everything involving the spirit, are perfect and eternal gestures that remain and will always remain in the spirit of man’ (Second Manifesto of Spatialism, 1948-1949, reproduced in R. Miracco, Lucio Fontana: At the Roots of Spatialism, exh. cat., Estorick Collection of Modern Art, London, 2007, p. 37). Existing eternally, the tagli achieve a near spiritual state of transcendence, capturing the essence of the immaterial in a gesture that encompasses the mysterious and unmeasured dimension of space and time, while remaining, like the pervasive, essential presence of sunlight on the earth, of this world.

Lucio Fontana, Milano, 1964. Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana / SIAE / DACS, London 2015.

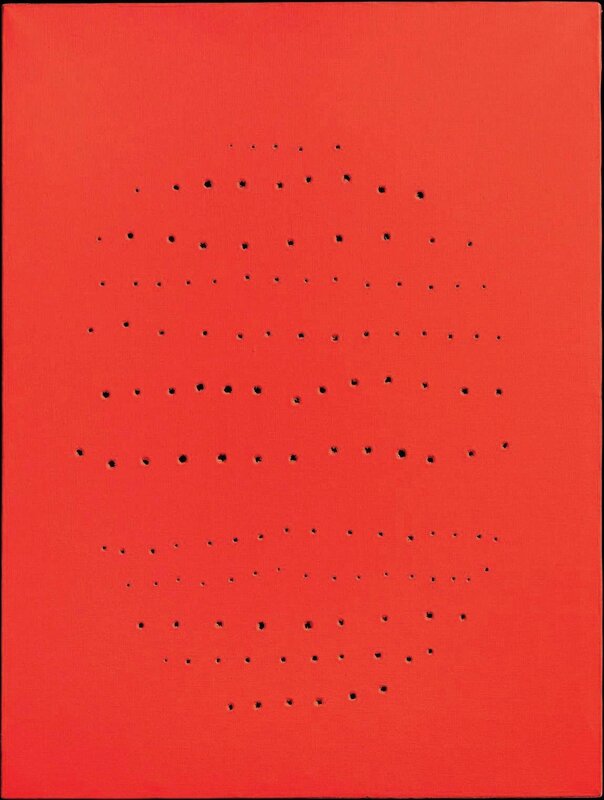

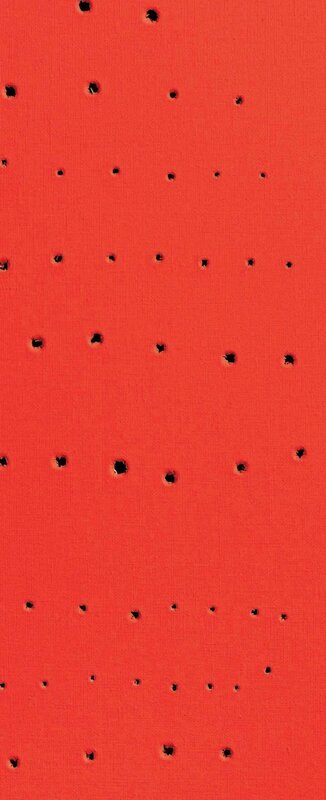

Lot 56. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale; signed, titled and inscribed ‘l. fontana concetto spaziale 1+1 - AE75’ (on the reverse); waterpaint on canvas; 24 x 18 1/8in. (61 x 46cm). Executed in 1960. Estimate: £500,000 – £700,000 ($792,000 - $1,108,800). Price realised GBP 518,500. Photo: Christie's Image Ltd 2015.

Provenance: Private Collection, Milan.

Galleria Tega, Milan.

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo generale, vol. I, Milan 1986, no. 60 B 41 (illustrated, p. 246).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. I, Milan 2006, no. 60 B 41 (illustrated, p. 405).

Notes: ‘The discovery of the cosmos is a new dimension, it is infinity, so I make a hole in this canvas, which was at the basis of all the arts and I have created an infinite dimension... the idea is precisely that, it is a new dimension corresponding to the cosmos... The hole is, precisely, creating this void behind there... Einstein’s discovery of the cosmos is the infinite dimension, without end. And so here we have: foreground, middleground and background... to go farther what do I have to do?... I make holes, infinity passes through them, light passes through them, there is no need to paint’(L. Fontana, quoted in C. Lonzi, Autoritratto, Bari 1969, pp. 169-171).

‘I do not want to make a painting – I want to open up a space’ (L. Fontana, 1965, quoted in E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I, Brussels 1974, p. 7).

xecuted in 1960, Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale belongs to his ground-breaking series of Buchi (Holes). With its punctured, flaming red monochrome surface and its constellation of holes arranged into an oval, it is also a work that relates to – and perhaps anticipates – one of Fontana’s greatest series, La Fine di Dio (The End of God) begun in 1963. It was through the Buchi that Fontana first began to translate his Spatialist adventure and initiated his explorations into the unknown dimensions beyond the canvas. By confronting and piercing the canvas, the artist physically and conceptually destroys it as a two-dimensional space of representation and form. In doing so, he gave birth to an art that goes beyond the limits of the traditional flat painted surface. Through this gesture, Fontana believed he had opened art to new and limitless creative possibilities.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, La Fine di Dio, 1963. Private Collection © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2015.

Fontana’s term Concetto spaziale (Spatial Concept) first appeared in 1946 shortly after the publication of the Manifiesto Blanco, a document that outlined the research carried out by a group of artists under Fontana’s leadership. The concepts conveyed in this Manifesto would be further extended in the Manifesto dello Spazialismo published in 1947. Together, these Manifestos presented a call for new forms of art that drew inspiration from the innovative technologies now available to mankind. Fontana thus invited other contemporary artists of the time to release art from the burden of representation and overcome the constraints associated with traditional painting. Initiated in 1949, the Buchi represented Fontana’s first expression of these new concepts.

Fontana’s enduring fascination with the cosmos and the exploration of space is materialized in this Concetto spaziale through the instinctive yet calibrated piercings that form a constellation on the surface of the canvas. The holes created are the traces of the artist’s movements, representing physical expressions of Fontana’s transcendence of the picture plane. The work also articulates Fontana’s exploration of space and light. With its vibrant red monochrome surface, the work glows as if with an inner energy. As we pass in front of the canvas, we notice light passing through the holes, creating a fantastic shimmering effect that invites the viewer to enter into the immaterial voids created by the Buchi. The flat surface gives a sense of calm and seemingly devoid of artistic touch. This effect is dramatically interrupted by Fontana’s punctures, enacted with violence and precision to reveal the space that lies behind the ‘sacred’ conventional picture plane.

Salvador Dalí, Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man, 1936. Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg. ©Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2015.

The egg-like shape created by Fontana’s arrangement of holes can be seen also to symbolise the birth of a new conception of art. This concept was ultimately immortalized in the renowned Fine di Dio series, which features the same oval composition as the present work. The meaning of the title Fine di Dio is a metaphor for the end of all religions, philosophies and other now obsolete earthbound thinking, while the oval form symbolises the genesis of a new era. By punctuating the canvas to form an egg-like shape, as in the present work, the artist performs an act of destruction and yet, at the same time, one of creation: the birth of Spatial Art. As Fontana wrote, ‘the discovery of the cosmos is a new dimension, it is infinity, so I make a hole in this canvas, which was at the basis of all the arts and I have created an infinite dimension... the idea is precisely that, it is a new dimension corresponding to the cosmos... The hole is, precisely, creating this void behind there... Einstein’s discovery of the cosmos is the infinite dimension, without end. And so here we have: foreground, middleground and background... to go farther what do I have to do?... I make holes, infinity passes through them, light passes through them, there is no need to paint’ (L. Fontana, quoted in C. Lonzi, Autoritratto, Bari 1969, pp. 169-171).

Lucio Fontana creating buchi, 1964. Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana / SIAE/ DACS, London 2015.

Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale; signed and dated ‘l. fontana 56’ (lower right); signed ‘l. fontana’ (on the reverse); oil, sand and glitter on canvas; 23 5/8 x 19¾in. (60 x 50cm.). Executed in 1956. Estimate: £400,000 – £600,000 ($633,600 - $950,400). Photo: Christie's Image Ltd 2015.

Provenance: G. Pomè Collection.

Galleria Flaviana, Locarno.

Private Collection, Milan.

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 1998.

PROPERTY FROM A EUROPEAN GENTLEMAN

Literature: G. Ballo, Fontana. Idea per un ritratto, Turin 1970, no. 224, p. 258 (titled Autoritratto (Concetto spaziale); illustrated in colour, p. 184).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue Raisonné, Brussels 1974, vol. I, no. 56 BA 23 (illustrated, p. 52); vol. II, no. 56 BA 23 (illustrated, p. 48)

E. Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan 1986, vol. I, no. 56 BA 23 (illustrated, p. 173).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Milan 2006, vol. I, no. 56 BA 23 (illustrated, p. 326).

Exhibited: Milan, Galleria Pagani del Grattacielo, Autoritratto, 1956.

Verona, Palazzo Forti, Lucio Fontana metafore barocche, 2002-2003, no. 6 (illustrated in colour, p. 33).

Notes: ‘A form of art is now demanded which is based on the necessity of this new vision. The baroque has guided us in this direction, in all its as yet unsurpassed grandeur, where the plastic form is inseparable from the notion of time … This conception arose from man’s new idea of the existence of things; the physics of that period reveal for the first time the nature of dynamics. It is established that movement is an essential condition of matter as a beginning of the conception of the universe’ (L. Fontana, trans. C. Damiano, Manifesto tecnico dello Spazialismo, 1951, reproduced inLucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 2006, p. 229).

Like rudimentary symbols carved into an ancient planetary landscape, the glittering, encrusted surface patterns of Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale embody the visionary splendour of the artist’s early investigations. Executed in 1956, it stems from the series of Barocchi or ‘Baroque’ works that represent an important milestone in the development of Fontana’s ‘Spatialist’ aesthetic. Created between 1954 and 1957, the Barrochi formed a critical bridge between the mystical opulence of the Italian counter-reformation – a period that had long fascinated Fontana – and the futuristic age of space exploration from which his practice took its cue. Working with rich, tactile concoctions of oil, sand and glitter, he forged fluid geological terrains, sparkling sediments and mysterious ciphers: fragile vestiges of kinetic potential that seemed to point to alternative realms of being. Variously punctured by rows of small holes, the work is conceptually related to the series of Buchi (‘Holes’) that Fontana had begun in 1949, and whose invocation of the dimension beyond the pictorial surface would ultimately give way to his iconic slashed paintings several years later. Poised on the brink of a new frontier, with Russia’s launch of Sputnik the following year, Concetto spaziale illustrates Fontana’s burgeoning attempts to breed a new artistic language, straining to reconcile past and present as science and technology raced towards an unknown future. A formative body of work within the artist’s oeuvre, examples from theBarocchi series are held in institutions including the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, the Museu d’Art Contemporani, Barcelona, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome and the Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna. Shown in the year of its creation in an exhibition entitled Autoritratto (Self-Portrait) at the Galleria Pagani del Grattacielo, Milan, it is a work that is closely connected to Fontana’s sense of artistic identity at this critical moment in his career.

Fontana’s relationship with the Baroque had begun early in his practice, exemplified by his mosaic-covered sculptures and near-Futurist forms of the 1930s. However, it was not until much later that he was able to articulate the connection between his admiration for its aesthetic and the conceptual aims outlined in his Spatialist manifestoes. For Fontana, the seventeenth-century’s invocation of unearthly extravagance and metaphysical ecstasy found new expression in man’s desire to penetrate the cosmos, to shatter the boundaries of time and space and glimpse the incomprehensible vastness of infinity. In the Barocchi, Fontana sought to consecrate this lineage. Writing in 1951, the artist explained that ‘A form of art is now demanded which is based on the necessity of this new vision. The baroque has guided us in this direction, in all its as yet unsurpassed grandeur, where the plastic form is inseparable from the notion of time … This conception arose from man’s new idea of the existence of things; the physics of that period reveal for the first time the nature of dynamics. It is established that movement is an essential condition of matter as a beginning of the conception of the universe’ (L. Fontana, trans. C. Damiano, Manifesto tecnico dello Spazialismo, 1951, reproduced inLucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 2006, p. 229). Contrasting their deliberately earthbound materiality with their invocation of dimensions beyond the canvas, Fontana’s Barocchiillustrate his early alignment with the conceptual aims of Art Informel. Like the raw, caustic topographies of Antoni Tàpies and Jean Fautrier, Concetto spaziale shimmers with flashes of figuration, traces of recognisable forms turned to ashes and dust. Yet, unlike much of their work, Fontana’s canvases are not conceived as sites of debris nor relics of human presence: rather, they are active celebrations of the energy latent within physical matter. They are not dead remains but dynamic launch-pads – platforms from which we might begin to catch sight of the new, uncharted dimensions that were increasingly within man’s grasp.

Alfredo Jaar, Milan, 1946: Lucio Fontana visits his studio on his return from Argentina, 2013. (detail). Collection GAM, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Torino. © Archivi Farabola. Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg/Cape Town, Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano/Napoli, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin, kamel mennour, Paris, and the artist, New York.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F00%2F33%2F119589%2F114771064_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F15%2F77%2F119589%2F112861527_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F67%2F10%2F119589%2F112573706_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F18%2F119589%2F112434153_o.jpg)