Sumptuous East Asian Lacquer, 14th–20th Century

For more than two millennia, lacquer has been a primary medium in the arts of East Asia. This installation explores the many ways in which this material has been manipulated to create designs by painting, carving, or inlaying precious materials such as gold or mother-of-pearl. Drawn entirely from the permanent collection, this display celebrates the artistry and creativity needed to work this demanding material while illustrating both the similarities and differences found in the lacquer arts of China, Korea, and Japan.

Tray with flowering plum and birds, early 15th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay; H. 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm); W. 11 3/4 in. (29.8 cm); L. 24 3/8 in. (61.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Lent by Florence and Herbert Irving (L.1996.47.39). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The wonderful flowering plum tree and two plump birds that fill the center of this tray illustrate the skillful manipulation of shapes and colors of the inlaid motherof-pearl to create a powerful, dramatic scene. Long narrow pieces of iridescent shell define the rock terrain, while irregular pieces form the clump of rocks in front of the trunk of the flowering plum. Fragments of mother-of-pearl create the craggy trunk of the ancient tree, which bears buds in several stages of flowering.

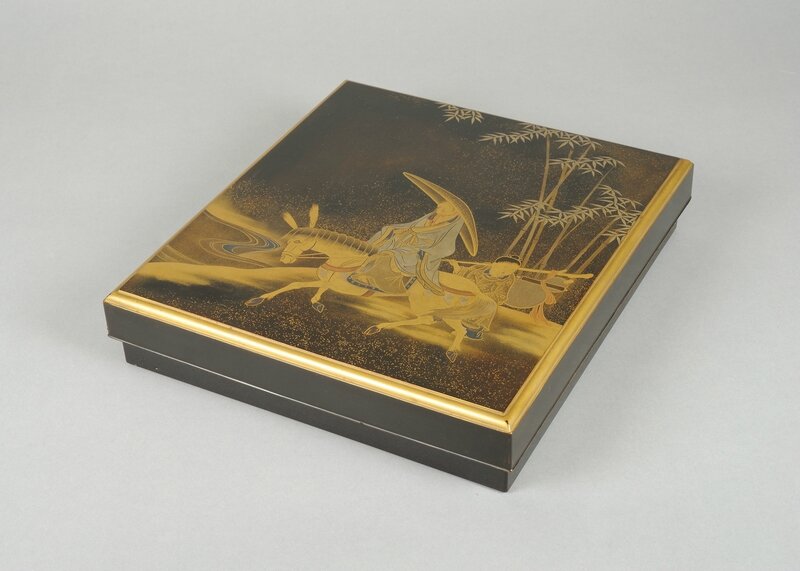

Writing Box with Chinese Poet Su Dongpo and Attendant, second half of the 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Black lacquer with gold, silver, and red togidashimaki-e; H. 1 7/8 in. (4.8 cm); W. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm); D. 9 3/4 in. (24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1881 (81.1.170). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This writing box depicts one of the most famous poets and statesmen in Chinese history, Su Dongpo (also known as Su Shi, 1037–1101). He is often represented riding on the back of a donkey, a poor man’s conveyance and a symbol of the eremitic life of a scholar-poet. His young attendant is holding a gourd presumably filled with wine, which also helps identify the figure as Su Dongpo, who was also famed for his consumption of this beverage. The lush and detailed surface of this box was created by burnishing sprinkled gold and silver powders to achieve a smooth surface, a technique known as togidashimaki-e.

Writing Box with Design of Plum Blossoms and Moon, 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Reddish-brown lacquer with gold hiramaki-e, lead, and mother-of-pearl inlay; H. 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm); W. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm); L. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891 (91.1.630). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Both Chinese and Japanese poetry contain allusions to the delicate beauty of plum blossoms in the moonlight and their subtle fragrance. This literary allusion underlies the imagery on this box and is particularly appropriate to its function as a container for an ink stone and brushes.

Incense Box with Fragrant Grass Design, 14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Carved black, red, and yellow lacquer; H. 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm); Diam. 3 3/8 in. (8.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891 (91.1.645). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Box with Geometric Designs, late 17th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay; H. 1 1/8 in. (2.9 cm); Diam. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891 (91.1.672). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The five distinct geometric patterns on this box are composed of extraordinarily small, thin fragments of pearl shell. This is a refined version of the technique of inlaying mother-of-pearl into a black lacquer surface that was developed in the twelfth century. Fragments of pearl shell were sometimes tinted or painted on the back to enhance their natural colors, such as pink and green.

Writing Box with Yellow Rose Flowers and Rushing Stream, 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Black lacquer with gold and silver takamaki-e, hiramaki-e, togidashimaki-e and cutout gold foil application; 2 In. (5.1 cm); W. 10 in. (25.4 cm); D. 9 in. (22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913 (14.40.832a–m). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The lid of this box is decorated with yellow kerria rose blossoms (yamabuki ) in arching sprays with bright green leaves. These flowers are associated with the Ide no Tamagawa (Jewel River) near Kyoto, a link that may have been formed after the respected poet and official Tachibana no Moroe (684–757)planted them on the banks of the river. The Ide no Tamagawa has long been featured in Japanese poetry:

The bottom of the Tama River at Ide

Reflecting the image above,

Is so clear that flowers of the

Yellow kerria add layer upon layer

Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114–1204)

Box with Pommel Scroll, late 13th–14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Carved red and black lacquer; H.1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm); Diam. 5 in. (12.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.713). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ubiquitous in the decoration of carved lacquer and also found in clay and metal, the design on this box was designated the “pommel scroll” as early as the Song period (960–1279), and this term is widely used in the cataloguing of lacquer. It refers to the pommel of a sword, which is an unexpected prototype for a design in another material. The Japanese term guri, or bent wheel, is also sometimes used to categorize lacquers with this design.

Screen with Birthday Celebration for General Guo Ziyi, dated 1777. Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95). China. Carved red lacquer; Open flat: 84 1/8 in. × 12 ft. 4 in. (213.7 × 375.9 cm) Open curved: 84 1/8 in. × 11 ft. 3 13/16 in. × 35 7/16 in. (213.7 × 345 × 90 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Henry-George J. McNeary, 1971 (1971.74a–h). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This lacquer screen shows the bustling activity accompanying a birthday party in a large residential compound. An inscription on the back of the screen indicates that it was made in honor of a certain General Zhen. The image on the screen is an often depicted scene of a celebration in honor of Guo Ziyi (697–781), one of the most famous generals in Chinese history. The use of this particular subject would have been an obvious compliment to General Zhen, and the screen may have been presented to him on an important occasion, perhaps his sixtieth birthday.

Box with Peonies, 15th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle period (1403–24). China. Carved red lacquer; H. 2 3/4 in. (6.4 cm); Diam. 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur M. Sackler Gift, 1974 (1974.269a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Frequently depicted in carved lacquer, peonies are important in East Asian art and are understood as symbols of royalty, rank, wealth, and honor. On this box, additional flowers (camellias, tree peonies, pomegranates, and chrysanthemums) are carved along the sides. This is one of several pieces in the collection carved with a six-character mark reading “Made during the reign of the Yongle Emperor” (Da Ming Yongle nian zhi ) on the bottom. Use of such marks, which are more commonly found in ceramics, began in the early fifteenth century and continued in all media into the twentieth. Works so marked are thought to have been produced for the court.

Sutra Box with Dragons amid Clouds. Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle period (1403–24). China. H. 5 1/2 in. (14 cm); W. 5 in. (12.7 cm); L. 16 in. (40.6 cm; H. 2 3/4 in. (6.4 cm); Diam. 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sir Joseph Hotung and The Vincent Astor Foundation Gifts, 2001 (2001.584a–c). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Vigorous, sinewy dragons are frequently depicted on works produced during the reign of the Yongle emperor. Intended to hold a Buddhist text made in the Chinese handscroll format, elegant boxes like this one were produced for both use at the court and as diplomatic gifts, particularly to Tibet.

Tray with Scene from the Tale of Genji, early 17th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Black lacquer with gold maki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay; H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm); W. 30 1/8 in. (76.5 cm); D. 16 1/8 in. (41 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation Gift, 2002 (2002.2). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Dish with Two Boys, 16th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China.Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay. H. 3/4 in. (1.9 cm); W. 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm); D 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm); Diam. 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Vincent Astor Foundation Gift, 2005 (2005.265). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chest with a Single Drawer, late 16th–early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Japan. Gold lacquer with hiramaki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay; gilt copper fittings; H. 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm); W. 13 3/16 in. (33.5 cm); L. 19 7/16 in. (49.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Barbara and William Karatz Gift, 2008 (2008.182a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This spectacular chest belongs to a category of goods known as nanban (literally southern barbarians), produced for trade with Portugal and other European countries in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. While the shape of the chest derives from European traditions, the geometric patterns on the top and sides were most likely influenced by the Indian textiles that were widely traded at the time. On the other hand, the delicate floral scroll on the front is an East Asian motif, imported into Japan from China around the eighth century.

Shibata Zeshin (Japanese, 1807–1891), Tiered Food Box with Summer and Autumn Fruits, ca. 1868–90. Meiji period (1868–1912). Japan. Brown lacquer with gold, silver, and colored lacquer maki-e; H. 16 1/8 in. (41 cm); W. 9 in. (22.9 cm); D. 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Vincent Astor Foundation Gift and Parnassus Foundation/Jane and Raphael Bernstein Gift, 2010 (2010.143a–g). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This box, designed for the storage and serving of sumptuous edibles at festive occasions, has a continuous design of summer and autumn fruits, including grapes, melons, loquats, and pears. The lacquer ground is a rich, very dark brown decorated with metal and colored lacquer applied using a variety of techniques to create the different fruits.

Box with Pommel Scrolls, first half of the 14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Carved red and black lacquer (tixi). H. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm); W. 4 5/8 in. (11.7 cm); L. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.1a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The pommel scroll is so-named because it resembles the shape of a Chinese sword pommel. This design is often seen in objects decorated with layers of contrasting colors of lacquer, particularly red and black. Found predominantly on ceramics, metalwork, and lacquer from the thirteenth century, there is no known explanation for the creation and popularity of this motif. However, it may have been inspired by the antiquarianism of the period, when motifs that were based on, or presumed to be based on, the Chinese Bronze Age were incorporated into the designs of many types of objects.

Tray with Pommel Scrolls, 14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Carved red and black lacquer. H. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm); W. 6 1/2 (16.6 cm); L 9 1/2 in. (24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.2). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Box with Dragons amid Clouds, late 13th–early 14th century. Southern Song (1127–1279)–Yuan (1271–1368) dynasty. China. Carved black, red, and yellow lacquer. H. 3 in (7.6 cm); Diam. 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.4a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The feline dragons that curve along the surface were inspired by comparable creatures found on Bronze Age vessels rediscovered during the Song dynasty and often reinterpreted in the arts of that period. Although they lack the large heads, horns, and prominent snouts often seen in Chinese depictions, they remain auspicious and protective.

Box with Garden Scene. Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle period (1403–24). China. Carved red lacquer. H. 2 7/8 in. (7.3 cm); Diam. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sir Joseph Hotung and The Vincent Astor Foundation Gifts, 2001 (2015.500.1.6a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

On the cover, two men seated on a veranda overlook a body of water while relaxing. One plays the zither, the other listens. Three attendants, one inside the nearby pavilion, also enjoy the music. Such scenes, which depict the cultured lifestyle of the scholarly class and record their artistic skills, became ubiquitous in Chinese painting and decorative arts after the fourteenth century.

Cabinet with Figures in a Landscape, 18th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong period (1736–95). China. Carved red lacquer; H. 13 in. (33 cm); W. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm); L. 35.9 in. (35.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.10a–e). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This two-door cabinet looks as if it is two separate boxes held together by the gilt-bronze handles at the top, but it is actually a single piece. The six side panels are decorated with figures along a riverbank or on a garden terrace by the water, with receding hills in the far distance. The tops of the two drawers are adorned with deer in a landscape. The sharp, precise carving of the red lacquer is characteristic of works produced in Qianlong workshops, as is the deeply carved brocade pattern that serves as the background.

Tray with Figures in a Landscape, 16th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay; H. 1/8 in.; Diam. 10 5/8 in.(27 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.13). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The scene on this dish, which shows a gentlewoman, her maid, and two young attendants walking toward a young man hiding near a pavilion on a moonlight evening, suggests a romantic tryst. It may derive from Romance of the West Chamber, China’s most popular love story. Written by Wang Shifu (ca. 1260–1336) during the Tang dynasty (681–907), it is a tale about star-crossed lovers: Zhang Sheng, a young impoverished scholar; and Cui Yingyin, the daughter of a high-ranking official.

Box with Peony Scrolls, 15th–16th century. Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). Korea. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay; H. 3/4 in. (1.9 cm); W. 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); L. 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.3.2a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Korean lacquers from the early Joseon period expanded on the earlier tradition of using mother-of-pearl inlay by covering the entire surface with a single element, such as the peony scroll on this box. The use of slightly larger pieces of pearl shell and a greater interest in negative space also help to distinguish this box from those produced in the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries.

Incense Box with Pommel Scroll Design, 13th–14th century. Southern Song (1127–1279)–Yuan (1271–1368) dynasty. China. Carved polychrome lacquer. H. 1 3/8 in. (3.6 cm); Diam. 4 in. (10 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.17a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This design is commonly known as the "pommel scroll" pattern because the bracket-shaped scroll resembles the pommel of a Chinese sword. The design was popular in lacquer, ceramics, and metalwork in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and remained important in carved lacquer in the fifteenth century.

Lobed Box, 14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay and pewter wires. H. 7 in. (17.8 cm); Diam. 8 5/8 in. (22 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.21a–c). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lacquer boxes with lobed sides and pewter trim are unique to the Yuan dynasty. Many were fitted with an interior tray that probably held cosmetics, combs, hairpins, and other adornments.

Tray with Pommel Scroll, 14th century. Yuan (1271–1368)–Ming (1368–1644) dynasty. China. Carved red and black lacquer. H. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm); Diam. 12 1/2 in. (31.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.24). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Tray with Women and Boys on a Garden Terrace, 14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Carved red lacquer. H. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm); Diam. 21 7/8 in. (55.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.31). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A masterpiece for its the lush carving and size, this tray depicts two women and twenty-three children on a terrace near a pavilion overlooking a lotus pond. One woman is seated on an openwork seat, the other stands. She holds one child and another clutches her skirt. A third crawls toward them. One of the boys is hiding in a rock, three play in a shallow tub of water, two ride hobby horses (a toy perhaps invented in China), and several take part in a procession that likely imitates those of court officials, a common site in major Chinese cities in the fourteenth century.

Lozenge-Shaped Dish with Garden Scene, 14th century. Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). China. Carved red lacquer. H. 7/8 in. (2.2 cm); W. 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm); L. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.32). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The scholar gentleman walking with his attendant, who is holding a zither, appears to be leaving his pavilion, either after having just participated in an event or perhaps on his way to another that would have included music, poetry, painting, and wine.

Dish with Immortals Playing Weiqi. Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Xuande period (1425–46). China. Carved red and green lacquer. H. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm); W. 5 7/8 in. (14.9 cm); L. 9 1/4 in. (23.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.33). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The shape of this dish, often described as a lotus, appears to have been produced primarily during the short reign of the Xuande emperor. The figures playing weiqi, a chesslike game known in Japan as go, in a remote location under moon light, can be identified as Daoist immortals by their clothing—for example, the short cape of leaves worn by the figure seated with his back to the composition. Immortals playing chess in remote locations are often found in Chinese art and literature.

Sutra Covers with the Eight Buddhist Treasures. Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle period (1403–24). China. Red lacquer with incised decoration inlaid with gold. L. 28 1/2 in. (72.4 cm); W. 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm); H. of each cover 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.52a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This pair of sutra covers was made for an edition of the Tibetan Buddhist canon, comprising 108 volumes, produced in Beijing at the order of the emperor in 1410. A triple flaming jewel—symbolic of the Buddha, his teaching, and the monastic community—is the central motif. Four additional emblems, part of a set known as the Eight Treasures, flank the jewels. Inscriptions in Tibetan and Chinese on the back of each set of covers identify the texts once contained within, in this case a volume listing the names of the one thousand Buddhas born in the current cosmic era.

Pair of Sake Caskets, late 16th–early 17th century. Momoyama period (1573–1615). Japan. Red and black lacquer (Negoro ware). L. 9 5/8 in.(24.5 cm); W.9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm); H. 20 in. (50.8 cm); W. 4 7/8 in. (12.4 cm); L. 15 1/4 in. (38.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.2.17a–d). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Red lacquer utensils were produced in Japan as early as the Heian period (794–1185). During the subsequent Kamakura period (1185–1333), Buddhist monks at the Negoro-ji temple in present-day Wakayama Prefecture began producing furnishings covered in red lacquer layered over black lacquer. Wares made using lacquer in this manner later became known as Negoro wares.

This pair of sake casks could be suspended by cords from the two rings at the top and easily transported. Such casks were often used as congratulatory gifts. The earliest surviving examples date to the early sixteenth century.

Writing Box with the Poet Kakinomoto Hitomaro (died 715), 17th–18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Black lacquer with gold and silver takamaki-e, hiramaki-e, cutout gold and silver foil application; lead rim. L. 9 5/8 in.(24.5 cm); W.9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm); H.2 in. (5.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.2.19a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

His posture as he reclines on an armrest with his hand atop his left knee and his concentrated expression identify this figure as Kakinomoto Hitomaro, the patriarch of Japanese poetry. Believed to have been born near Nara, Hitomaro served at the court and later as a provincial official.

Hitomaro’s poems are often suffused with a deep personal lyricism. The imagery on the inside of this box illustrates one of his most famous works:

Dimly through morning

Mists over Akashi Bay my

Longings trace the ships

As they vanish beyond

the island.

Box for Books with Waterfall, 16th century. Muromachi period (1392–1573). Japan. Lacquered wood with gold and silver takamaki-e, hiramaki-e, cut-out gold and silver foil application and silver inlay on black lacquer ground. L.10 1/4 in. (26 cm); W. 71/4 in. (18.4 cm); H. 1 7/8 in. (4.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.2.20a, b). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Originally this extravagantly decorated box held books, which could be pushed up through a hole at the base. It was later converted into a box for writing implements. The decoration of a pine, cypress, plum, and camellia set in a mountainous landscape with a waterfall and temples fills the entire surface of the box, from the top to the beveled sides, and remains uninterrupted whether the box is open or closed. The decoration may refer to classical poetry, though the scene cannot be definitively identified.

Food Box with Striped Decoration and Chinese Figures, early 17th century. Momoyama (1573–1615). Japan. Black lacquer with gold and silver maki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay. H. 10 5/8 in. (27 cm); W. 7 11/16 in. (19.5 cm); D. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.2.31a–f). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The geometric patterns on the side of this tiered food box derive from Indian and Southeast Asian textiles introduced to Japan as part of the global trade that linked different parts of Asia with each other and with the West. The clothing and setting identify the three figures on the top of the box as Chinese, and it is possible that this use of figural imagery was spurred by an awareness of the depiction of figures in contemporaneous lacquer from China and Okinawa (Ryūkyū Islands).

Box with Crabs and Waves, 17th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Lacquered wood with gold hiramaki-e and e-nashiji on black lacquer ground; H. 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm); W .6 in. (15.2 cm); L.12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Barbara and William Karatz Gift, 2008 (2015.500.2.33a–f). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The somewhat unusual shape of this box suggests that it might have been used to hold implements for painting, such as ink stones, brushes, and pigments. Variations in texture on the crab shells and in the rendering of the dramatic waves are a result of the different sizes and densities of the sprinkled gold, and of the various methods used to apply the gold powder. This box, with its bold and decorative design, could have been used by a well-to-do individual living in a cultural center such as Edo (present-day Tokyo)or Kyoto.

Stationery Box with Moon and Autumn Grasses, 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Black lacquer with powdered and sprinkled gold and silver hiramaki-e and silver foil application; H. 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm); W. 5 7/8 in. (14.9 cm); L. 9 1/4 in. (23.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Barbara and William Karatz Gift, 2008 (2015.500.2.42a–c). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The almost indiscernible bits of silver foil and powder that line the edges of the wild grasses, bush clover, and miscanthus are intended to illustrate the reflection of bright moonlight in an autumn field. Also found in China, the custom of holding moon-viewing parties is thought to have begun in Japan during the Heian period (794–1185). In addition to contemplating the harvest moon, offering sake while praying for an abundant harvest and writing poetry were also part of the festivities.

Dish with Garden Scene, 15th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Carved red lacquer. H. 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm); Diam. 7 3/34 in. (19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015 (2015.500.1.73). Photo: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The elegant grounds and inviting pavilions that are often depicted on Chinese carved lacquer in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries reflect the prevalence of such settings in the cities of southern China, where they served as venues for entertainment and as private spaces conducive to self-reflection and renewal.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F45%2F84%2F119589%2F128381154_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F25%2F119589%2F128370615_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F95%2F119589%2F126875799_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F72%2F119589%2F122505070_o.jpg)