Exhibition of masterpieces from the Austrian Hapsburg dynasty brings imperial splendor to Atlanta

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (Italian, 1527-1593), Fire, 1566, oil on panel, 26 3/16 × 20 1/16 inches (66.5 cm × 51 cm). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

ATLANTA, GA.- A major American collaboration brings masterworks amassed by one of the longest-reigning European dynasties to the High Museum of Art. “Habsburg Splendor: Masterpieces from Vienna's Imperial Collections,” on view Oct. 18, 2015, through Jan. 17, 2016, showcases masterpieces and rare objects from the collection of the Habsburg Dynasty—the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire and other powerful rulers who commissioned extraordinary artworks now in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

“Habsburg Splendor,” largely composed of works that have never traveled outside of Austria, was co-organized by the High, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Key masterpieces traveling for the first time to the United States include:

· “The Crowning with Thorns” (c. 1602/1604) by Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi, called Caravaggio (Italian, 1571 - 1610), Christ Crowned with Thorns, ca. 1603. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

With violence and pathos we witness one of Christ's last earthly sufferings. He slumps to one side as his dirty, ragged tormentors pummel him with sticks. The bright red of his cloak offers a premonition of his bloody fate on the cross, as we, along with a disturbingly disinterested soldier, watch the terrible story unfold. Caravaggio, one of the great innovators of the Italian Baroque, amplified the drama of the scene through his striking use of light and dark and strong diagonals.

· A portrait of Jane Seymour (1536), Queen of England and third wife to Henry VIII, by Hans Holbein the Younger

Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497 - 1543), Jane Seymour, ca. 1536. Oil on oak. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Jane Seymour was the third and favorite wife of the English King Henry VIII—the only one of his six wives to produce a male heir who survived infancy. She died a few days after giving birth. Henry VIII likely commissioned the work for himself, but it was in the Habsburg collection by 1720. Holbein emphasized Jane's prim piety and regal bearing. She wears a necklace with the monogram of Christ (IHS), reminding viewers that while Henry had separated England from the papacy, it was still a devout state.

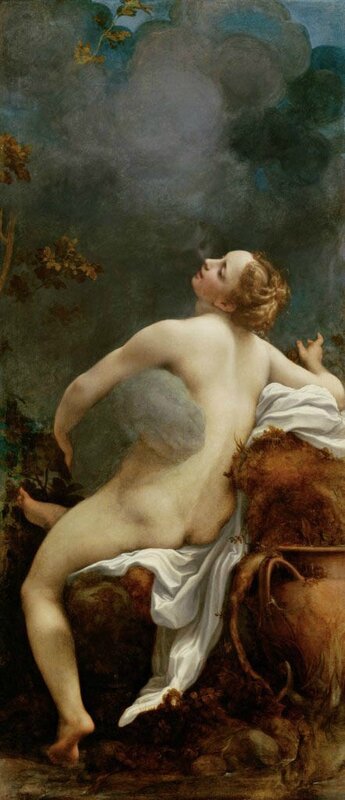

· “Jupiter and Io” (c. 1530/32) by Correggio

Antonio Allegri, called Correggio (Italian, 1489 - 1534 ), Jupiter and Io, ca. 1530 - 1532. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

This masterpiece by Correggio remains one of art history's most daring, erotic, and shocking paintings. Correggio painted four sensuous canvases relating Jupiter's loves. In Roman mythology, the lusty god often disguised himself so he could seduce maidens without his wife, Juno, catching on. On a sunny day, here he has become a thick black cloud. Jupiter's face faintly appears in the blackness as he reaches his great, paw-like arm to embrace the nymph Io.

“For many visitors, this exhibition is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to explore hundreds of years of art collecting by the Habsburg family,” said Gary Radke, consulting curator for the High. “Viewers will find themselves feeling a bit like royalty, sensing both the wealth of these extraordinary rulers and the splendid attention they paid to detail in all of their works of art.”

“We’re delighted to share our Museum’s unique wonders with our American friends,” said Sabine Haag, general director of Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. “The exhibition will show the extraordinary wide range of the Habsburgs’ collections, including masterpieces of Roman antiquity, medieval armory, early modern painting and craftwork, as well as gorgeous carriages and clothing. We hope this will inspire visitors to make the trip to Vienna to see the collection in person and to discover even more of our treasure.”

“Habsburg Splendor: Masterpieces from Vienna's Imperial Collections” chronicles the Habsburgs’ story in three chapters, each featuring a three-dimensional “tableau”—a display of objects from the Habsburgs’ opulent court ceremonies—as context for the other works on view.

DAWN OF THE DYNASTY

The first section features objects commissioned or collected by the Habsburgs from the 13th through the 16th centuries. In this late medieval/early Renaissance period, Habsburg rulers staged elaborate commemorative celebrations to demonstrate power and to establish their legitimacy to rule, a tradition that flourished during the reigns of Maximilian I and his heirs. Works from this era—including sabres and armor, tapestries, Roman cameos, and large-scale paintings—illustrate the significance of war and patronage in expanding Habsburg influence and prestige.

Tableau: Suits of armor displayed on horseback and jousting weapons from a royal tournament

Highlights include:

• Armor of Emperor Maximilian I (c. 1492) made by Lorenz Helmschmid

Lorenz Helmschmid (German, ca. 1445 - 1516), Composed Armor for Emperor Maximilian I, Augsburg, 1492. Iron, brass, leather. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

• Bronze bust of Emperor Charles V (c. 1555) by Leone Leoni

Leone Leoni, (c. 1509–1590) 'Emperor Charles V', c. 1555, Milan. Bronze. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

• A rock crystal goblet made for Emperor Frederick III (1400–1450)

Goblet with lid, so-called Herberstein Goblet, early 15th century. Base: prior to 1449; lid: 1564. Rock crystal, silver, and gold plate. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

This precious goblet was owned by Fredrick III (1415-1493), whose personal mark (AEIOU) is inscribed beside the year 1449 on its base. The vowels AEIOU are probably an abbreviation for the first letters of the words in the Latin phrase, "It is Austria’s duty to rule the entire world." The goblet was cut from a single piece of rock crystal. To emphasize his material’s preciousness and his own virtuosity, the carver made a 12-sided goblet. In the medieval world, the number 12 symbolized perfection.

GOLDEN AGE

The second and largest section of the exhibition highlights the apex of Habsburg rule, the Baroque Age of the 17th and 18th centuries. The dynasty used religion, works of art, and court festivities to propagate its self-image and claim to rule during this politically tumultuous time. Paintings by Europe’s leading artists demonstrate the wealth and taste of the Habsburg rulers, while crucifixes wrought in precious metals and gems, as well as sumptuous ecclesiastical vestments, reflect the emperor’s role as defender of the Catholic faith.

Tableau: A procession featuring a Baroque ceremonial carriage and sleigh, with carvings by master craftsman Balthasar Ferdinand Moll

Highlights include:

• An ivory tankard (1642) by Hans Jacob Bachmann

Hans Jakob I. Bachmann, goldsmith (German, 1574 - 1651), Master IPG, ivory carver (Active c. 1640), Lidded Tankard in Ivory with Bacchanalia and Mythological Scenes, 1642. Ivory and gilt silver. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Scenes of drunken revelry adorn this elaborate ivory tankard. Bacchus, god of wine, pursues a nymph while his cohort of revelers surrounds him, laughing, playing music, and harvesting grapes. At the top of the lid, a small figure of Amor, god of love, observes the path of an arrow he appears to have just shot. Such imagery is connected to the intoxicating contents the tankard was made to hold – though it's likely it was never actually used as a drinking vessel. Instead, the magnificent ivory and gilded silver object was displayed as a symbol of the Habsburg's wealth and refinement.

• “Infanta Maria Teresa” (1652–53), a portrait of the daughter of Philip IV of Spain and eventual wife of Louis XIV of France, by Velázquez

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599 - 1660), Infanta Maria Teresa, ca. 1652–1653. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Before photography and widespread travel, painted portraits of marriageable young girls were often sent to the families of potential husbands for vetting. The young Spanish infanta Maria Teresa was considered as a spouse for several Habsburgs, and multiple portraits of her, including this one, were sent to Vienna. Ultimately, she married her cousin, King Louis XIV of France.

In this portrait, Maria Teresa is fashionably attired, and her expression, along with the spontaneity of the artist's brush, projects a fresh, lively appearance.

• An alchemical medal (1677), illustrated with portraits in relief of the Habsburgs, by Johann Permann

Johann Permann, Alchemical Medallion, November 15, 1677. Gold-silver-copper cast. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria.

Johann Permann, Alchemical Medallion -reverse side, November 15, 1677. Gold-silver-copper cast. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria.

TWILIGHT OF THE EMPIRE

The exhibition concludes with works from the early 19th century, when the fall of the Holy Roman Empire gave rise to the hereditary Austrian Empire—a transition from the ancien régime to a modern state in which merit determined distinction and advancement. Franz Joseph, who would reign longer than any previous Habsburg, saw the growth of nationalism and ultimately ruled over a dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. As heir to the Habsburg legacy—and in the spirit of public education and enrichment—he founded the Kunsthistorisches Museum in 1891. Reflecting the modernization of the Habsburg administration, the exhibition will end with a spectacular display of official court uniforms and dresses.

Tableau: Uniforms and women’s gowns from the court of Franz Joseph

Highlights include:

• Campaign uniform of Franz Joseph (1907)

• A velvet dress made for Empress Elisabeth (c. 1860/65)

• An evening gown made for Princess Kinsky (c. 1905)

• Ceremonial dress of Crown Prince Otto for the Hungarian Coronation (1916)

Regalia of a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen, 1764. Silk velvet, silk, faux ermine, gold embroidery, and feathers. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

The colors of the vestments worn by the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen are those of Hungary: red (for the robe), green (for the cape), and white (for the faux ermine edging). All the clothes are embroidered with golden oak leaves, referencing the ancient Roman tradition of honoring extraordinary citizens with oak wreaths.

The Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary was founded by Empress Maria Theresa in 1764. Unlike other orders whose members were equal peers, this order provided an opportunity for the emperor to recognize individuals of various origins and rank for their outstanding civil service.

Regalia of a Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, 18th century. Silk velvet, silk, and gold. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Since its founding by the Duke of Burgundy in 1430, the Order of the Golden Fleece has been one of the noblest chivalric orders. It initially took its name from the ancient hero Jason and his Argonauts but also became identified with Gideon's fleece, which marked him as leader of the Hebrew people. The order came under Habsburg auspices when Maximilian I married Mary of Burgundy in 1477. It later split—like the family—into Spanish and Austrian branches.

In the style of Charles Frederick Worth, Black Velvet Dress Belonging to Empress Elisabeth, ca. 1860–1865, restored 1998 and 2014. Velvet and silk. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Empress Elisabeth, better known by her nickname, Sisi, became one of the first female celebrities of the modern world. A passionate athlete and competitive horse rider, she had a fitness center set up in the imperial palace and was known for her unconventional views of court society and her vigorous fights with her mother-in-law. Incredibly slim, her "Vienna wasp waist" became the height of fashion. It was especially accentuated in a relatively unadorned but elegant day dress like this one.

The exhibition is curated by Dr. Monica Kurzel-Runtscheiner, director of the Imperial Carriage Museum, Vienna. At the High, the consulting curator is Gary Radke, professor emeritus of art history at Syracuse University.

Northern Italian Artist, All’antica morion of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol, 1560.Blued, embossed iron, gilded and silvered, with gold damascene work. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The style of this helmet reflects the popularity of Greek and Roman antiquity during the Renaissance. The visage of a dragon dominates the front of the helmet, its ferocious mouth opening just above the wearer’s face. The sides are adorned with scenes of mythology, including Poseidon, god of the sea, in a carriage drawn by seahorses. Such an elaborate and decorative helmet would have been worn at festive occasions and not during battle.

Attributed to Nikolaus Pfaff (German, ca. 1556 - 1612), Goblet of Rhinoceros Horn, ca. 1610–12. Rhinoceros horn. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Drinking from this cup would have guaranteed a happy and healthy love life. Three satyrs, mythical creatures who, being part animal and part human, could not control their sexual desires, form the base of this goblet. They morph from the zoological to the human to the botanical as their animal legs support human arms that turn into branching coral. Rhinoceros horn was thought to be an aphrodisiac (sexual stimulant) and to ward off evil and bad luck, as was coral.

Giorgio da Castelfranco, called Giorgione (Italian, 1477 - 1510), The Three Philosophers, ca. 1505. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Here three men of differing ages lose themselves in thought before a cave. The youngest sits with a square and compass, the oldest stands with a compass and a tablet, the man in the middle wears Oriental dress and a turban.

Giorgione's painting may or may not have a specific subject. The three figures could represent the three earliest Greek philosophers seeking to understand the principles of nature or illustrate the three ages of man. No matter what, Giorgione's poetic manner encourages thoughtful contemplation and inventive interpretation by viewers, too.

Jacopo Robusti, called Tintoretto (Italian, ca. 1518 - 19 - 1594), Susanna and the Elders, ca. 1555–56. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

According to the biblical book of Daniel, one hot afternoon Susanna decided to bathe in a garden fountain. Two elderly men watched on the sly and then propositioned her. The virtuous Susanna refused them but was subsequently charged with adultery. During her trial, the elders' treachery was revealed, and they were put to death.

This poetic painting sparkles with color and light. The dramatic diagonal composition, lushness of the garden, and the imposing figure of Susanna draw us in, despite the leering presence of the peeping toms.

Andreas Möller (Danish, 1684 - ca. 1762), Maria Theresa as a Child, ca. 1727. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Maria Theresa was already poised and charming at age 10. To preserve Austrian Habsburg rule in the absence of male heirs, her father, Emperor Charles VI, declared that daughters of royal princes could succeed to the Habsburg throne. Here Maria Theresa poses with an archducal hat behind her right hand, indicating she is already invested with authority. Her ermine lined cape reinforces her nobility.

Attributed to Lorenz Helmschmid (German, ca. 1445 - 1516), Boy’s Jousting Armor of Archduke Philip I, "the Fair," ca. 1490–95. Armor: iron, brass, and leather; targe: wood, bone(?), and leather. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

This suit of jousting armor, consisting of a metal bodice and helmet, a wooden lance, and a leather shield, was made for young Philip I, also known as "Philip the Handsome" or "the Fair." Even young noblemen participated in jousting tournaments, a form of military training that evolved into an elite sport. Participants charged toward one another on horses, aiming their pointed lances at their opponent's shield. Although meant to simulate combat, jousting often took place at festive social events that also included music, dancing, and grand processions.

Coral Saber (Coltellaggio) and Scabbard for Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol, 1560. Coral, gilt silver, steel, wood, and velvet. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Archduke Ferdinand II was an avid collector of rare objects made of coral, which was believed to have mythical powers and protect against the evil eye. In this example, the spindly, bright-red branches form the handle of this coltelaggio, or large knife. Because coral was costly and brittle, weapons such as this one were purely for show and were worn with antique-style armor in festive processions. The only coral-handled sabers that have survived from the Late Renaissance all derive from Ferdinand II's collection of wonders.

Jörg Seusenhofer (Austrian, ca. 1510 - 1580), Hans Perckhammer (Unknown nationality, 1527-1557), Armor for Plankengestech from the "Eagle Garniture" of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol, 1547. Iron, brass, leather, and cloth. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The “Eagle Garniture" of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol is the most extensive ensemble of armor still in existence, and the best documented. Its 87 parts may be assembled 12 different ways, depending on the use, such as equestrian or pedestrian combat or for various types of tournaments. The "Eagle Garniture" was first worn by Ferdinand II at a tournament in Prague in early 1548. Its name comes from the Austrian heraldic eagle that adorns many of its pieces.

Bust of Emperor Claudius, ca. 41 - 54. Light gray chalcedony and gold-plated silver, early 1600s, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

As Holy Roman Emperors, the Habsburgs looked to ancient Rome for artistic inspiration and validation of their authority. They displayed Roman portrait sculptures in the grand public spaces of their palaces, often restoring ancient pieces with more modern parts, as in the case of this portrait cameo. Habsburg emperors commissioned exquisite portraits that were equally Roman looking, linking themselves visually to ancient rulers as well as claiming superiority through technically advanced marble-carving technique.

Leonhard Kern (German, 1588 - 1662), Abundantia, ca. 1635–1645. Walrus tusk. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In this sculpture, nature transforms into a work of art. Carved from a piece of walrus tusk, this voluptuous female figure standing with a cornucopia of fruit represents Abundantia, the goddess of plenty or Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees and orchards. The natural form of the material—in particular, the ivory’s grainy structure— is incorporated into the design. This texture is especially visible on the goddess's shoulders, arm, and left leg. This tension between art and nature was characteristic of cabinets of curiosities of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian, and Workshop (Italian, ca. 1488 - 1576), Danaë, ca. 1554 - 1565. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In this sumptuous Venetian Renaissance painting, Titian, one of the great masters of that time, returned to a subject he painted many times: the myth of Danaë. According to mythology, Danaë's father, the king of Argos, received a prophecy that his daughter's son would one day kill him. In order to prevent Danaë from ever bearing such a child, the king locked her in a dungeon. This painting shows Danae visited by Jupiter in the form of a cloud of gold, impregnating Danae and fulfilling the prophecy. It was sent as a gift to Emperor Rudolf II in 1600.

Jan Thomas (Flemish, 1617 - 1678), Emperor Leopold I, 1667. Oil on copper. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

On January 24, 1667, an equestrian ballet was performed on the Burgplatz in Vienna to celebrate the wedding of Emperor Leopold I and the Spanish infanta Margarita Teresa. This small painting shows Leopold in his costume for the event. The ballet told the story of a competition between the Four Elements. Air or water, aided by fire and earth—which had created the most beautiful pearl? It didn't really matter. The point was the spectacle and that the bride was the perfect pearl. In Latin, Margarita means pearl.

Bernardo Bellotto, known as Canaletto (Italian, 1722 - 1780), Schönbrunn from the Cour d’Honneur, ca. 1759–1761. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In this painting, Bernardo Bellotto depicted the immense palace and courtyard of Schönbrunn, Maria Theresa's favorite summer residence, just west of Vienna. Maria Theresa and her courtiers stand in the distance on a balcony of the left wing of the imperial palace. In the middle ground, Count Joseph Kinsky's carriage barrels across the court, followed by his galloping entourage, bringing word of a Habsburg triumph over the Prussians. The painting carries the date August 16, 1759, when Maria Theresa received this news, not when the painting was completed.

Gala Carriage of the Vienna court— The "Princes' Carriage," ca. 1750–55. Wood panels, bronze, glass, iron, velvet, silk, and gold embroidery. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Attributed to the Imperial Saddlery, Two Sets of Harnesses from a Six-Horse Gala Team, ca. 1740–50. Leather, velvet, gilt brass, gold, and silk passementerie. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

This fashionable gala carriage carried the imperial family’s children during formal processions in Vienna. A window was added on the back in 1896 to display the transport the Hungarian crown jewels.

The lavish appliqué and gilded cast-brass buckles on these two sets of harnesses, from a required set of six, are particularly splendid. They show the coat of arms of the non-ruling members of the imperial house, the Austrian coat of arms with the archducal coronet above, and intricate scrollwork and strapwork typical of the Baroque style.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F68%2F37%2F119589%2F128313729_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F15%2F78%2F119589%2F127923120_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F42%2F119589%2F122236959_o.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F90%2F14%2F119589%2F117943406_o.jpg)