Exhibition of classic ukiyo-e spanning 100 years on view at Scholten Japanese Art

Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825), "Women Washing and Stretching Cloth", each sheet signed Toyokuni ga, with censor's kiwame (approval) seal and publisher's seal of Tsutaya Juzaburo (Koshodo, 1750-1797), ca. 1795, oban tate-e triptych 28 1/8 by 14 5/8 in., 71.5 by 37 cm. Asking price: $14,000. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

NEW YORK, NY.- Scholten Japanese Art participates in Asia Week 2016 with Ukiyo-e Tales: Stories from the Floating World, an exhibition focused on classic Japanese woodblock prints.

This exhibition will take us back to the golden age of ukiyo-e and will feature works by some of the most important artists of the late 18th and up to the mid-19th century. We will focus predominately on images of beauties and the layers of meaning and stories that are conveyed via subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) clues found in the compositions. The exhibition will begin with works by Suzuki Harunobu (ca. 1724-70), who is largely credited with bringing together all of the elements that launched the production of nishiki -e (lit. brocade pictures), the full-color prints that we recognize today as ukiyo-e or images of the floating world. The term ukiyo (lit. 'floating world') references an older Buddhist concept regarding the impermanence of life, but during the prosperity of the Edo period in Japan the term began to be used to encompass and embolden everyday indulgences because of that impermanence. It was Harunobu's designs, primarily celebrating youth and beauty, that are believed to have first launched the production of full-color woodblock printing in Japan around 1765.

One of the finest Harunobu prints included in this exhibition, Fashionable Snow, Moon, and Flowers: Snow, ca. 1768-69 depicts an elegant courtesan accompanied by her two kamuro (young girl attendants) and a male servant holding a large umbrella sheltering her from falling snow. The subject, a beautifully adorned courtesan parading en route to an assignation, and her placement within the lyrical setting of an evening snowfall, are hallmarks that define the genre of ukiyo-e. There are relatively few Harunobu prints extant, and due to their scarcity and the fragile nature of the vegetable pigments used at that time it is unusual to find a work in such good condition. Hence there are only two or three other authentic impressions of this particular design which have been recorded in public collections.

Suzuki Harunobu, ca. 1724-70, "Fashionable Snow, Moon and Flowers: Snow" (Furyu Setsugekka: Yuki), signed Suzuki Harunobu ga, ca. 1768-69, chuban tate-e 11 by 8 in., 27.8 by 20.3 cm. Sold. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

An elegant beauty is accompanied by two young girls and a male servant who holds an umbrella to shelter her from falling snow. Seeking the warmth within her layers of clothing, she tucks her chin into her collar, and hides her hands within the robes. Her brocade obi is tied in a large knot at the front identifying her as a courtesan, and her pink outer-robe is decorated with folding fans and braches of blossoming plum- a wishful harbinger of early spring. The two young girls in her retinue, attired in matching apparel and sharing their own smaller umbrella, are herkamuro- children attendants assigned to a specific courtesan of ranking house. The fresh snow gathers in clumps around the platforms of their lacquered geta (raised sandals) while large flakes of falling snow contrast against the pale grey pigment in the background with some areas of oxidation which emphasizes an evening setting. The procession is likely en route to an assignation: parading the courtesan with her attendants in all of their collective splendor was an important opportunity for pageantry in the ritual of seduction in the pleasure quarters.

This design is part of a group of three which reference the classical trio of Snow, Moon and Flowers (Settsugekka), from a poem by Bai Juyi (772-846) which is included in the anthology Wa-Kan roei shu (734). The poem on the print above the stylized cloud focuses on the snow.

Shirotae no

masago no ue ni

furisomete

omoishi yori mo

tsumoru yuki kana

On the pure white of

the sand it has started to

fall, sinking in: just

look how the snow is piling

up, deeper than expected!

Waterhouse records only two other impressions of this design which he dates to circa 1768-69. One is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (acquisition no. 06.465); the other is in the collection of The New York Public Library (acquisition no. 135, D-12). He identifies four other examples as either late impressions from the 19th century with recarved color blocks or reproduction prints.

References: David Waterhouse, The Harunobu Decade, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2013, Vol. I, p. 211, cat. 342 (from the Spaulding Collection, accession no. 21.4498) and poem translation.

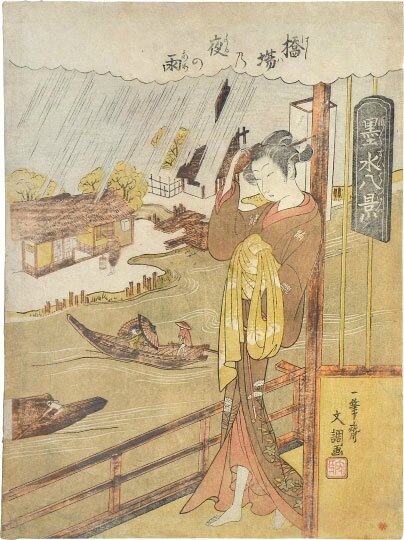

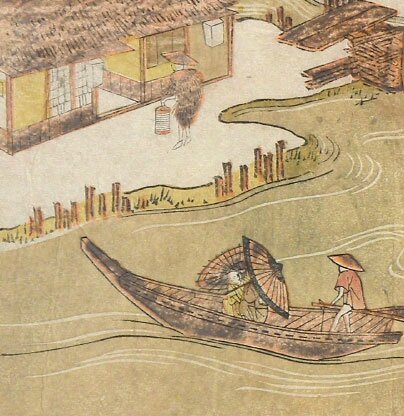

A print by a contemporary of Harunobu, Ippitsusai Buncho (fl. ca. 1755-90), titled Eight Views of Inky Water: Night Rain at Hashiba, ca. 1768-75, depicts the world from the perspective of a courtesan, without the pageantry of her parade through the pleasure quarters. Stepping out on to the verandah overlooking the Sumida River, she seems lost in thought as she adjusts the comb in her hair and looks down towards the small ferry boats navigating the dark ('inky') waters during a rainstorm while the passengers try vainly to protect themselves from the downpour. Streaks of rain partially obscure the view across the river where we see a figure carrying a lantern approaching a teahouse near the shore at Mukojima. While it was not uncommon to use accepted themes such as landscapes or literary subjects as a way to circumvent restrictions on overt depictions of famous actors and beauties or decadent displays of wealth, most of the time the 'cover' subject was relegated to an inset cartouche and the figural subject was front and center. In this composition the figure and the landscape are given equal consideration in a way that is unusual for the period because the landscape in the background tells as much of the 'story' as the figure in the foreground.

Ippitsusai Buncho, fl. ca. 1755-90, "Eight Views of Inky Water: Night Rain at Hashiba" (Bokusui hakkei: Hashiba no yoru no ame), signed Ippitsusai Buncho ga with artist's seal Mori uji, with collector's seal HV (Henri Vever), ca. 1768-75, chuban tate-e 10 1/4 by 7 3/4 in., 26 by 19.6 cm. Price: $14,500. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

The series title Bokusui hakkei (Eight Views of Inky Water) is a reference to the Sumida River- the primary conduit for Edoites to the various entertainment districts, including the licensed pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara. The title itself is presented within a cartouche in the shape of asumi ink cake, while the specific location of Hashiba is identified above the cloud-shaped reserve. The Hashiba ferry would carry patrons of the Yoshiwara across the Sumida River to the landing on the eastern shore at Mukojima- a scenic area with teahouses along the shore.

The composition depicts a willowy courtesan adjusting her haircomb while standing on a second story balcony overlooking the Sumida River. She looks down towards the small ferry boats navigating the dark ('inky') waters during a rainstorm; the passengers in one boat shield themselves from the downpour beneath two interlocking umbrellas. The streaks of rain partially obscure the view across the river where we see a single figure wearing a straw rain cape and holding a lantern approaching a teahouse near the shore at Mukojima.

Provenance: Louis Gonse (1846-1921)

Henri Vever (1854-1942)

Published: Jack Hillier, Japanese Prints & Drawings from the Vever Collection, 1976, p. 223, cat. no. 237

References: Sadao Kikuchi, A Treasury of Japanese Wood Block Prints: Ukiyo-e, Tokyo National Museum, 1963, cat. no. 418 (with series cartouche and half of the signature trimmed)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (www.mfa.org), from the Spaulding Collection (Ex. Kobayashi Collection), accession no. 21.4697

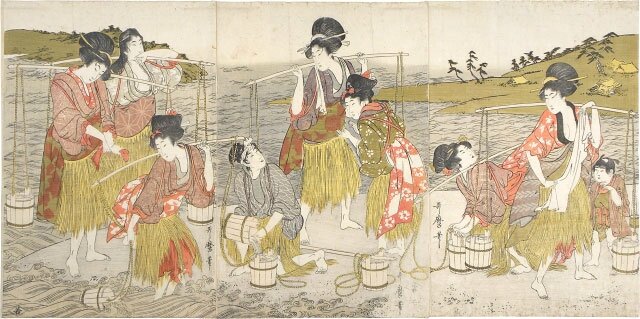

Another important artist well-represented in the show is Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), a leading painting and print artist in his time, who practically owned the market for images of beauties in the 1790s and early 1800s, until his untimely death in 1806 shortly after a traumatizing episode when he was made to wear manacles under house arrest in punishment for having the audacity to depict the shogunate in an irreverent manner. A triptych of 'Brine Carriers' at a seashore was produced in happier times and visually references a classical literary subject, the sisters Matsukaze ('Wind in the Pines') and Murasame ('Autumn Rain'), from the famous 14th-century Noh Drama, Matsukaze . Although the original story is about love and loss, Utamaro only barely references the cautionary legend and instead focuses on the opportunity to sidestep restrictions and depict women in revealing clothing in an everyday setting. The two sisters have been replaced by a bevy of beauties wearing grass skirts far shorter than acceptable in normal public settings, and their kimono tops are literally falling open while they wade in the surf collecting the brine.

Kitagawa Utamaro, 1753-1806, "Brine Carriers" (Shiokumi), each sheet signed Utamaro hitsu, with publisher's seal Waka, of Wakasaya Yoichi (Jakurindo), ca. 1804, oban tate-e triptych 29 3/4 by 14 5/8 in., 75.5 by 37.3 cm. Asking price: $26,000. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

This triptych depicting a group of beautiful woman gathering brine at a seashore gently references a classical literary subject, the sad story of the two sisters, Matsukaze ('Wind in the Pines') and Murasame ('Atumn Rain'), from the famous Noh drama, Matsukaze, which was written in the 14th century by Kanami, and revised by his son Zeami Motokiyo (c. 1363-c.1443). The story is based on the legend of the nobleman Ariwara no Yukihira who spent three years in exile at Suma. While expelled to the shrine famously located at a beach, he indulged himself in dalliances with two sisters who were lowly salt-collectors. Shortly after his punishment is ended and he abandons them to return to court, they hear that he had died, causing the sisters to die of broken hearts themselves, but their spirits remain trapped, lingering at the beach at Suma because of the sin of attachment to mortal passions. In the play, Matsukaze's spirit continues to descend in to madness, while her sister Murasame's spirit eventually releases herself from her desires and is able to transcend beyond the physical world.

The story was adapted as a puppet play by Chikamatsu Mozaemon (1653-1725) and eventually as akabuki drama which was subsequently condensed into a hengemono (multi-role) dance, Shiokumi (Dance of the Salt Maidens), performed as an interlude between other plays. Utamaro's interpretation of Shiokumiexpands the theme to a gathering of seven beauties with one young man one child at the edge of the foaming surf along a beach. They wear the costume of the salt maidens with rustic grass skirts and carry the buckets of brine suspend from yokes resting across their shoulders, but their tops also fall open revealing their bare breasts without too much concern for decorum. The mood among the beautiful laborers appears playful, far removed from the tragedy of the original legend.

References: Kiyoshi Shibui, Ukiyo-e Zuten Utamaro, 1964, 34.1.1-3

Gina Collia-Suzuki, The Complete Woodblock Prints of Kitagawa Utamaro, A Descriptive Catalogue, 2009, pp. 421-422

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (mfa.org), from the Bigelow Collection, accession no. 11.14470-1 (center and right sheets only)

Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org), from the Havemeyer Collection, accession no. JP1683.

Another story told by Utamaro is of a lovers' quarrel. Eight Pledges at Lovers' Meetings: Maternal Love between Sankatsu and Hanshichi, ca. 1798-99, is from a series that plays on puns referencing the classic landscape theme of Omi hakkei ('Eight Famous Views of Omi'). This print uses the word ' bosetsu ' in the title, which can be translated as 'a mother's constant love,' but also works as a pun for 'evening snow,' a clever reference to Hira no bosetsu ('Evening Snow on Mount Hira'), one of the Omi hakkei subjects. But clever wordsmithing aside, what makes this print so remarkable is the tiny gesture of the woman, holding her index finger to her eye to wipe away a tear. For all of the dramas and tragedies in ukiyo-e, this small display of emotion stands out. While there are numerous visual shortcuts that artists employed to convey elements to a story, such as wisps of hair being out of place signaling excitement (good or bad), wiping away a tear is not at all common. Even more telling is the body language of her lover, who is looming over her shoulder and glaring at her. Their story is from a kabuki play (based on a true incident), in which the lovers resolve to give up their daughter and commit double suicide. Thus the 'maternal love' in the title suggests Sankatsu's heartache over leaving her child, and it would seem Hanshichi is impatient with her hesitation. Utamaro, an artist known for his depictions of beautiful women of all ranks as well as erotic art, seems to convey his disapproval of their decision. Rather than feeding into the high drama in a way that romanticizes their story, Hanshichi especially is portrayed in an unflattering light.

Kitagawa Utamaro, 1753-1806, "Eight Pledges at Lovers' Meetings: Maternal Love Between Sankatsu and Hanshichi" (Omi hakkei: Sankatsu hanshichi no bosetsu), signed Utamaro hitsu, with publisher's mark Hon(Omiya Gonkuro of Shuhodo), ca. 1798-99, oban tate-e 15 1/8 by 10 in., 38.3 by 25.5 cm. Asking price: $22,000. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

This print is from a series of three-quarter length portraits of pairs of lovers from popular jojuripuppet plays. The series title, Omi Hakkei (Eight Famous Views), is a common classical theme which groups eight specific locations in Japan (originally based on the Chinese Eight Famous Views of the Xio and the Xiang) paired with eight set poems or images which was utilized in seemingly endless variations by ukiyo-e artists to present more decadent subjects under the guise of propriety. In this print, illustrating the lovers Sankatsu and Hanshichi, Utamaro refers to their affection for each other with the term bosetsu, which can be translated as 'a mother's constant love,' but also works as a pun for 'evening snow'- a clever reference to Hira no bosetsu ('Evening Snow on Mount Hira'), one of the set Omi Hakkei themes which is illustrated within the circular landscape cartouche.

The various plays popularly known as 'Sankatsu and Hanshichi' were based on a the true story of a love suicide that took place in the Sennichi burial ground in Osaka in 1695. Sankatsu was the adopted daughter of Minoya Heizaemon of Nagamachi and a courtesan in Osaka, and Akeneya Hanshichi was the son of a sakemerchant in Gojo in the Yamato Province. One of the first adaptions of the story was the play Hade sugata onna mai-ginue which was first staged as a Bunraku puppet play 1772. The story was not converted to a kabuki play until 1874. In the play, the lovers, who have a daughter named Otsu, decide to send the child to Hanshichi's parents carrying a suicide note (where is wife Osono has dutifully stayed with her in-laws) before they commit the act. This print seems to depict the climatic moment when Sankatsu weeps for her child and struggles with their decision, and Hanshichi, here noticeably impatient with her hesitation, urges her to go on, just before they exit the stage by running down thehanamichi in order to commit their suicide out of view.

The composition of this print is very remarkable in its overt display of emotion which is not often found in ukiyo-e subjects. In a genre that usually conveys passions with just a misplaced strand of hair, Utamaro takes a less restrained approach to communicate tensions between the lovers. Sankatsu is sits in crumpled dejection, her head lowered well below her shoulders and she wipes at the corner of her eye, surely in an effort to contain her tears. Hanshichi sits behind her, nearly looming over her shoulders and scowling in her direction. He holds his tobacco pipe vertically, the tip resting on his lap in a manner that mimics a ruler holding a scepter. Perhaps Utamaro's unflattering portrayal of the lovers reflects on his own disapproval of their tragic end.

References: J. Hillier, Utamaro: Colour Prints and Paintings, 1961, p. 124, cat. no. 80

Sugo Asano and Timothy Clark, The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, 1995, cat. nos. 296 and 323

There are several prints in the exhibition that show how young women, both in and out of the pleasure quarters, pass their time. Fashionable Five Festivals: Amusements of the Girls in the Seventh Month by Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) from ca. 1796 shows a young girl struggling with writing her poetic wish for the Tanabata Festival. She sits at a writing table, brush in hand, with all the accoutrements needed, but the blank paper looms before her. On the floor are completed poems on decorative paper, rejected or not, is unclear. But a companion at her side holds open a copy of the poetry anthology, Ehon hyakunin shu (Picture Book of One Hundred Poets), ready to provide inspiration to the young poetess.

Utagawa Toyokuni I, 1769-1825, "Fashionable Five Festivals: Amusements of Girls in the Seventh Month" (Furyu Gosekku: Fumizuki musume asobi), signed Toyokuni ga with publisher's seal Waka(Wakasaya Yoichi of Jakurindo), ca. 1796, aiban tate-e 13 1/4 by 9 in., 33.5 by 22.9 cm. Asking price: $3,800. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

A beauty seated at a writing table prepares to write a wish upon a narrow slip of paper which will be used as an ornament to hang on a bamboo decoration for the Tanabata Festival. On the desk are her necessary implements: a small inkstone and ink stick, additional brushes, a water dropper in the shape of a teapot, and extra paper in an array of colors. On the floor there is a small pile of decorative paper with completed (or rejected) wishes already inscribed on the top sheets. She pauses, brush in hand, and turns to confer with a companion seated at her side who holds open a copy of a poetry anthology, Ehon Hyakunin shu (Picture Book of One Hundred Poets). Branches of bamboo with Tanabata Festival ornaments are illustrated above within the reserve defined by a stylized cloud.

The Tanabata Festival (or Star Festival), held on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, is based on a legend associated with a celestial event- the meeting of the Vega star and the Altair star across the Milky Way, described in the legend of the married lovers, Orihime (the Weaving Princess, or the Vega star), and Hikoboshi (the Herdsman, or the Altair star). The pair were separated by Orihime's father, Tentei ('heavenly king') after they married because he was angry the Princess had stopped weaving her beautiful silks and Hikoboshi was neglecting his cows. He placed the Amanogawa River (a river of stars, ie. the Milky Way) between them and forbade the two to meet. He was eventually moved by his daughter's tears and relented, allowing them to reunite once a year on the seventh day of the seventh month.

Reference: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (www.mfa.org), accession no. RES.49.154

The private life of a courtesan inside the pleasure quarters is depicted by Kikugawa Eizan's (1787-1867) Twelve Hours in the Pleasure Quarters: Daytime, Hour of the Snake, Courtesan Tomoshie of the Daimonji, ca. 1812. The so-called hour of the snake was a two-hour increment that began around 10 in the morning. Here we see the courtesan Tomoshie who is just getting up. She barely keeps her lightweight kimono closed, exposing an astounding length of leg and a deep décolletage. She seems to have just finished washing up and is using the sleeve of her robe to dry behind her ears. A young assistant holding a bowl of water is not entirely put together herself; her robe is disheveled at the collar and is opening at the legs revealing her upper thigh.

Kikugawa Eizan, 1787-1867, "Twelve Hours in the Pleasure Quarters: Daytime, Hour of the Snake, Courtesan Tomoshie of the Daimonji" (Seiro juniji toki: Hiru mi no koku, Daimonji Tomoshie), signed Kiku Eizan hitsu, with censors kiwame(approved) seal and gyoji (publisher guild) seal,Tsusan (Tsumuraya Saburobei), and publisher seal Ezakiya (Ezakiya Ichibei of Tenjudo), ca. 1812, oban tate-e 14 7/8 by 10 in., 37.9 by 25.5 cm. Asking price: $6,000. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

It's mid-morning, the hour of the snake, at 10:00, and the courtesan Tomoshie is getting up at the Daimonji brothel. She stands barely dressed holding her yukata (light cotton kimono) closed just below her waist, exposing a deep décolletage and much of her bare legs. An ornateuchikake (outer-robe), perhaps tossed aside in haste the previous evening, is draped over thekimono rack to her left. An attendant kneeling at her side, possibly a shinzo (teenaged apprentice), holds a tray with a porcelain bowl filled with water which was likely used for washing up, as Tomoshie rubs the back of her neck and ear with the sleeve of her robe and wisps of hair fall into her face. The younger beauty who hasn't bothered to completely secure her rumpled kimono shows a flash of her upper thigh and also has a few strands of hair out of place, suggesting a morning rush in the household.

References: Eiko Kondo, ed., Eizan, Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, 1996, p. 63, no. 83

Minneapolis Institute of Art (collections.artmia.org), from the Hill Collection, accession no. P.78.65.95

While some prints provide titles and puns to help us identify the story behind the composition, others provide only oblique clues and leave the rest to our imaginations. A stunningly well-preserved print by Keisai Eisen (1790-1848), has a curious title that seems to marry manufacturing with artistry: Modern Specialties and Dyed Fabrics: Sound of Insects at the Bank of the Sumida, ca. 1830. While the series title references a certain type of cloth dyed in a dappled pattern, the print title evokes the poetic sound of insects along the Sumida River in the summertime, and the composition itself seems to have little to do with either. The image is of a woman reading a letter by the light of a lantern which casts a dramatic beam across the room. The temperature must be uncomfortably warm because she wears her kimono very loosely, leaving the collar wide open at her chest with the sleeves pushed up, allowing it to open between her thighs to reveal a suggestive view of the red under-robe. She sits awkwardly with her knees folded at an angle, hunched over a long scroll of paper with an anguished look on her face with tell-tale wisps of hair falling forward signaling her distress. What is in the letter? Why is she so intense? Is it good or bad? We don't know, her story is open for our interpretation.

Keisai Eisen, 1790-1848, "Modern Specialties and Dyed Fabrics: Sound of Insects at the Bank on the Sumida" (Tosei meibutsu kanoko: Sumida-tsutsumi no mushino oto), signed Keisai Eisen ga, with censor's seal kiwame(approved), publisher's mark Hei (Omiya Heihachi), ca. 1830, oban tate-e 13 7/8 by 9 3/4 in., 35.3 by 24.9 cm. Asking price: $3,800. Photo courtesy Scholten Japanese Art

An interior view of a young woman reading a letter by the light of an andon (lantern). The temperature must be uncomfortably warm- she wears her purple and green plaid kimono as loosely as possible, leaving the collar wide open at her chest with the sleeves are pushed up, and allowing it to open between her thighs revealing the red under robe, and there is a summer fan decorated with bonito fish and daikon (both summer foods) at her feet. The lantern casts a beam a light across the room, and a kimonodecorated with an auspicious bat pattern hangs to the side. She sits awkwardly with her knees folded at an angle, hunched over the long scroll of paper, with a look of anguish on her face. Wisps of hair fall into her face signaling her distress.

The term kanoko, in the series title, refers to a type of cloth dyed in a dappled pattern, worn by all of the beauties in this series.

Reference: Chiba City Museum of Art, Keisai Eisen: Artist of the Floating World, 2012, pp. 152-153 (series), p. 283, cat. no. 90-2

The exhibition will feature 48 woodblock prints including works by: Suzuki Harunobu (ca. 1724-70), Katsukawa Shunsho (1726-1792), Kitao Shigemasa (1739-1820), Katsukawa Shunko (1743-1812), Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Ippitsusai Buncho (fl. ca. 1755-90), Hosoda Eishi (1756-1829), Katsukawa Shunsen (1762- ca. 1830), Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825), Utagawa Toyokuni II (1777-1835), Chokosai Eisho (fl. ca. 1780-1800), Keisai Eisen (1790-1848), Kikugawa Eizan (1787-1867), and collaborative works by Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858); and one painting by Hosoda Eishi.

Gallery viewing will begin on Thursday, March 10th, and continue through Friday, March 18th. An online exhibition will be posted in advance of the opening at www.scholten-japanese-art.com. Scholten Japanese Art, located at 145 West 58th Street, Suite 6D, is open Monday through Friday, and some Saturdays, 11am - 5pm, by appointment. To schedule an appointment please call (212) 585-0474.

For the duration of the first segment of the exhibition, March 10 – 18, the gallery will have general open hours (no appointment needed), 11 am to 5 pm; and thereafter by appointment through March 31st.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F78%2F119589%2F126213120_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F71%2F11%2F119589%2F126205132_o.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F02%2F119589%2F121570920_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F87%2F77%2F119589%2F121450336_o.jpg)