Cardi Gallery at TEFAF Maastricht 2016

Lucio Fontana (Rosario 1899-1968 Varese), Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1968. Waterpaint on canvas, 61 x 50 cm. Signed twice, titled and inscribed on the reverse ‘I. Fontana “Concetto Spaziale” ATTESE il quadro è autentico I. fontana Comabbio 5-4-68’. Cardi Gallery © TEFAF Maastricht, 2016

‘Man today is too bewildered by the vastness of his world, he is too overwhelmed by the triumph of Science, he is too dismayed by the new inventions which follow one after the other, to be able to find himself in figurative painting. What is needed is an absolutely new language, a ‘Gesture’ purified of all ties with the past, which gives expression to this state of despair, of existential anguish’

(Fontana quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Venice and New York, 2006-07, p. 23).

Two vertical, parallel slashes dramatically rupture the immaculate, rich red monochrome surface of Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, Attese. Executed in 1964, this work is one of Fontana’s iconic series of tagli or cuts, which have come to serve as the epitome, both formally and theoretically, of Spatialism, the bold and radical movement that the artist founded in Milan in 1947. Inspired by the profound advancements in modern physics, science and space-travel, Fontana sought to create an art that corresponded with the newly discovered concept of the cosmos and the enigmatic fourth dimension. Iconoclastically incising the surface of the sacrosanct surface of the canvas to reveal a dark, mysterious space beyond and within, Fontana radically revised the conception of the picture plane, offering the viewer an experience of a new realm, an unknown and infinite dimension of the universe.

Fontana’s Spatialist theories were born out of a time of immense change during which scientific and technological advancements had led to radical reconfigurations in the way people regarded the universe and their place within it. Interplanetary travel and the galactic accomplishments of the era fascinated Fontana, as did Albert Einstein’s seminal scientific theories, which had introduced the concept of a space-time continuum: a fourth dimension of limitless, unfathomable and unconfined space. In the face of these explosive developments, the destiny of painting, particularly the brushstroke was, in the eyes of Fontana and his colleagues, outmoded and at risk of becoming antiquated and archaic.

A new form of art was needed, one which would correspond to the dawning of a new spatial era: ‘I assure you’, Fontana stated in 1949, ‘that on the moon they will not be painting, but they will be making Spatial art’ (Fontana quoted in S. Petersen, Space-Age Aesthetics: Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, and the Postwar European Avant-Garde, Pennsylvania, 2009, p. 6). While living in Argentina in the late 1940s, Fontana, along with a group of avant-garde artists, had conceived of an art that would emulate the spirit of the time. In 1946 they published Manifesto Blanco (White Manifesto), which called for art to transcend the traditional categories of painting and sculpture and instead explore the dynamic concepts of space, time and light; this new concept became known as Spazialismo (Spatialism).

A year later, on his return Milan, Fontana founded the Movimento Spaziale (Spatial movement), which further expounded the necessity for an art that could explore the limitless possibilities of the universe. In the First Spatial manifesto, published in 1947, the artists emphatically stated: ‘We refuse to believe that science and art are two distinct facts, that the gestures accomplished by one of the two activities cannot also belong to the other. Artists anticipate scientific gestures, scientific gestures always provoke artistic gestures’ (First Spatial Manifesto, 1947, in E. Crispolti and R. Siligato (eds.), Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Milan, 1998, p. 118). With his buchi (holes) and subsequently, tagli (cuts), which Fontana first began in 1958, the artist found a solution to his conceptual aims, discovering a means through which to transcend the inherent materiality and physicality of the canvas and instead invoke a perpetual spatial realm that would exist beyond the parameters of measurable time.

By piercing the canvas, Fontana created an object at once painting and sculpture, which could exist both in material space, while simultaneously denoting the immateriality of the mysterious void. With this act, Fontana, like the pioneering astronauts who probed the far-flung corners of the cosmos throughout the 1960s seeking to reveal the mysteries of the universe, sought to access and reveal to the viewer an unknown dimension beyond the surface of the canvas. Fontana explained, ‘the discovery of the cosmos is a new dimension, it is infinity, so I make a hole in this canvas, which was at the basis of all the arts and I have created an infinite dimension...the idea is precisely that, it is a new dimension corresponding to the cosmos... I make holes, infinity passes through them, light passes through them, there is no need to paint' (L. Fontana quoted in E. Crispolti ‘Spatialism and Informal. The Fifties’ in Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Milan, 1998, p. 146).

The two elegant cuts that slice through the canvas of Concetto spaziale, Attese represent both a conceptual and visual encapsulation of Fontana’s search for a new artistic language. All superfluous elements are eliminated, leaving only the artistic gesture, which resonates with a powerful serenity and stillness. For Fontana, the cut was an eternal gesture that, unlike the material itself, which would inevitably decay over time, existed without end; a means of artistic expression that would endure through time and space. Fontana and his Spatialist colleagues had stated in 1947, ‘We plan to separate art from matter, to separate the sense of the eternal from the concern with the immortal. And it doesn’t matter to us if a gesture, once accomplished, lives for a moment or a millennium, for we are convinced that, having accomplished it, it is eternal’ (First Spatial Manifesto, 1947, op. cit., p. 118).

Against the burning red canvas, in Concetto spaziale, Attese the evenly sized slashes have a sense of unique harmony, existing in a state of perfect equilibrium. The deep red monochrome background of Concetto spaziale, Attese imbues the work with a dramatic sensuality, accentuated by the violent yet elegantly refined cuts. It was with works such as Concetto spaziale, Attese, that Fontana achieved an absolute clarity, the highly concentrated act of slicing the canvas serving as the climax of his artistic explorations. As Fontana stated, ‘With the taglio I have invented a formula that I think I cannot perfect… I succeeded in giving those looking at my work a sense of spatial calm, of cosmic rigor, of serenity with regard to the Infinite. Further than this I could not go.’ (Fontana quoted in P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, p. 58).

Provenance: Lanzini Collection, Brescia; Private collection, Milan; Galleria Mirabello, Milan; Private collection, Italy; Cardi Gallery, Milan-London

Literature: E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnements spatiaux, vol. II, Brussels, 1974, no. 64 T 104, p. 158, ill. p. 159; E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo generale, vol. II, Milan, 1986, no. 64 T 104, ill. p. 536; E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. II, Milan, 2006, no. 64 T 104, ill. p. 722)

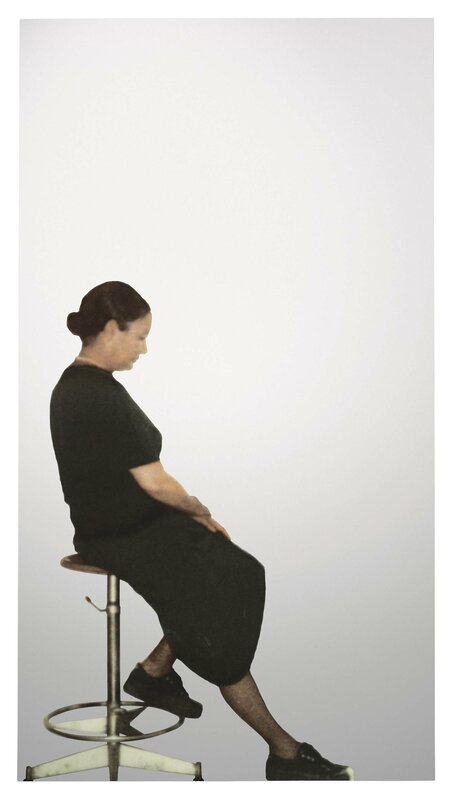

Michelangelo Pistoletto (1933), Maria a colori, 1962-1993. Silkscreen on polished stainless steel, 228.7 x 125 cm. Signed, titled twice and dated on the reverse 'Michelangelo Pistoletto 1962-93 Maria a colori (MARIA A COLORI)'. Cardi Gallery © TEFAF Maastricht, 2016

‘The viewer becomes the one who walks on the canvas—finds himself in the same space as the artist’, quote of M. Pistoletto in J. Lewinson, ‘Looking at Pistoletto / Looking at Myself’, J. Lewinson in K. Burton, (ed.) Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mirror Paintings, London 2010, p. 15.

Against the vast, expansive field of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Maria a Colori, a woman sits, solemn and introspective. Balanced on the brink, one foot tentatively testing the edge, Maria Pioppi, Pistoletto’s muse, ponders whether to step out of the mirror. Chancing across her in this quiet moment of contemplation, the curious sightseer becomes the furtive voyeur. Moving closer, seeking to discern more detail, the observer is suddenly stopped short: from within the depths of the work, another puzzled figure emerges, a second pair of eyes gaze questioningly back. A moment passes, and the viewer recognizes his own reflection – and in the instant of realization, he is doubled: transported into fictional space, to stand in the mirror beside the woman; yet remaining stubbornly, physically real. One of Pistoletto’s critically-celebrated series of mirror paintings, Maria a Colori is filled with mesmerizing potential: while the woman in the mirror remains lost deep in thought, the work changes to reflect the constant shifting of the universe – night falling, day dawning, stranger after curious stranger tracing on its surface. Maria Pioppi enraptured Pistoletto from their very first meeting in Rome in 1967.

Shortly after, Pistoletto began to feature her in the mirror paintings: she reclined gracefully in poses which recalled art historical masterpieces, such as Maria nuda (Maria Nude), 1967; or stood beside the artist in soulful portraits which evoked the intensity of their shared tenderness, as in Lei e Lui – Maria e Michelangelo (She and He – Maria and Michelangelo), 1968. In Maria a Colori, Maria is depicted some twenty-five years later. Here, she is a vision of consummate elegance: sitting poised, hands folded neatly in her lap, hair neatly coiled, dressed head to toe in understated black, which belies, with gentle irony, the work’s title. Time has passed, but the artist has remained captivated by the woman who has been not only a life-long companion but also an artistic collaborator. Alongside Pistoletto, Maria was a part of The Zoo, a circle of artists, writers, actors and musicians, active between 1968 and 1971, who were later recognized as instigators of Arte Povera.

Together, they performed spontaneous, chaotic theater in streets and piazzas throughout Italy, drawing on the rich traditions of wandering minstrels, travelling troubadours and Italian improvised theater, the commedia dell’arte. In anarchic performances whose plots were littered with illogical twists, Maria and Pistoletto played fantastically absurd roles, clad in costumes made up of colorful rags. ‘Everything could happen, and the opposite of everything,’ Pistoletto recalled their work with The Zoo. ‘Our stories and performances were born out of unexpected encounters, the moment, the chance’ (M. Pistoletto, quoted in A. Bellini (ed.), Facing Pistoletto, Zurich 2009, p. 58). The mirror paintings, too, were borne of a startling encounter: Pistoletto’s chance meeting with his likeness, reflected back at him from the surface of a painting he was working on. ‘In 1961, on a black background that had been varnished to the point that it reflected,’ the artist recalled this moment, ‘I began to paint my face. I saw it come toward me, detaching itself from the space of an environment in which all things moved, and I was astonished.’ (M. Pistoletto, quoted in Michelangelo Pistoletto, From One to Many, 1956-1974, exh. cat., Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, 2011, p. 143).

Fascinated by the cerebral interplay between painted image and reflected figure, Pistoletto began to explore materials and processes which would merge the two into a flawless, seamless unity. Maria a Colori, created in 1993, is the culmination of this technical investigation: the carefully composed silhouette is printed directly onto a dazzlingly polished sheet of steel, allowing permanent image and fleeting reflection to share the same surface. Maria a Colori is the point of origin from which space expands in multiple directions. The mirrored plane encompasses the physical surroundings before it, indiscriminately subordinating them to its reflective logic, and inverts them into a cavernous perspective. Throughout his practice, Pistoletto has understood art in terms of space: admiring, but ultimately rejecting the flatness of works by the Abstract Expressionists, made claustrophobic by their highly personal content, he instead turned to the perspectival illusions of the Renaissance for inspiration. Pierro della Francesca, Pistoletto proposed, 'put realistic figures in an abstract space. The space had its own presence, not as specific place, but as an indefinable void' (M. Pistoletto, quoted in K. Burton (ed.), Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mirror Paintings, Ostfildern 2011, p. 67).

In Maria a Colori, the artist updates these spatial experiments for the twentieth century, allowing perspectival geometry to engulf reality. Where the Renaissance had opened a window onto a fictional world, Pistoletto creates a door, inviting the viewer to step through. Within the mirror, the viewer is liberated, becoming an actor improvising in a theater of his imagination, following in the steps of Maria, Pistoletto and The Zoo. 'The step from the mirror paintings to theater – everything is theater – seems simply natural…,' the artist explained. 'It is less a matter of involving the audience, of letting it participate, as to act on its freedom and on its imagination, to trigger similar liberation mechanisms in people’ (M. Pistoletto, quoted in ‘Interview with G. Boursier’, in Sipario, April 1969, p. 17).

Provenance: Luhring Augustine, New York; Galerie Tanit, Munich; Private collection, Munich; Cardi Gallery, Milan-London

Exhibitions: New York, Luhring Augustine, Red Sky: Arte Povera, 2008; Munich, Galerie Tanit, Michelangelo Pistoletto. A selection of works from our shows 1982-2002, 2013; Beirut, Beirut Exhibition Center, Michelangelo Pistoletto, 2014-2015 ill. p. 8

Cardi Gallery (stand 535) at TEFAF Maastricht 2016.

Directors: Nicolò Cardi, Paola Zannini, Edoardo Osculati, Axel Benz, Nathalie Brambilla

Cardi gallery specializes in Italian modern and post-war contemporary art. In 1972, Renato Cardi founded the gallery to pursue his passion for promoting and collecting contemporary Italian artists. Today the gallery continue to be a platform to shape the arts and culture landscape globally. Four times a year the gallery produces major exhibitions by artists it represents as a mean of increasing its presence in the Italian art scene and every year participates in international art fairs. Through enhancing the inventory, the gallery also created significant private European collections. Cardi gallery lends regularly to major museums around the world.

Contact: Milan Venue: Corso di Porta Nuova 38, 20121 Milan, Italy. T +39 02 454 78 189 - F +39 0245478120 - www.cardigallery.com - mail@cardigallery.com

London Venue: 22 Grafton Street, London, W1s 4ex, United Kingdom. T +39 0245478189 - F +39 0245478120 - www.cardigallery.com - mail@cardigallery.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240313%2Fob_3da818_431115881-1632814154155264-57534444325.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240312%2Fob_cc9c83_f2.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240311%2Fob_2edda2_fontana.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F86%2F67%2F119589%2F129815803_o.png)