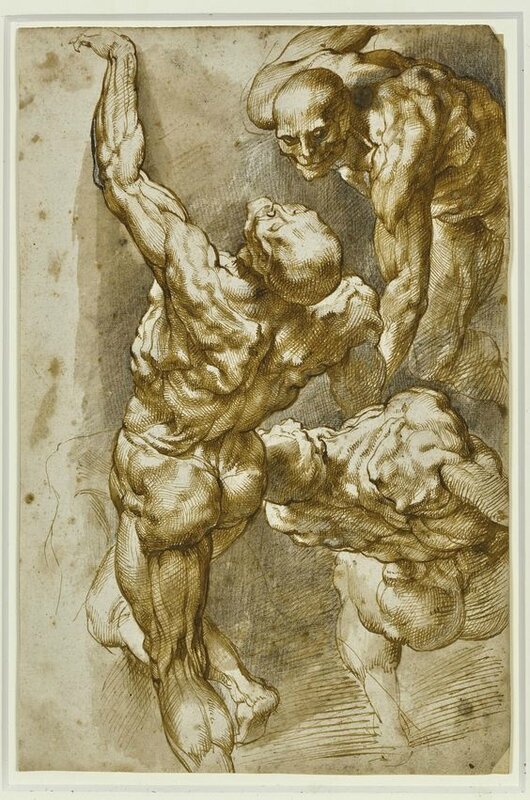

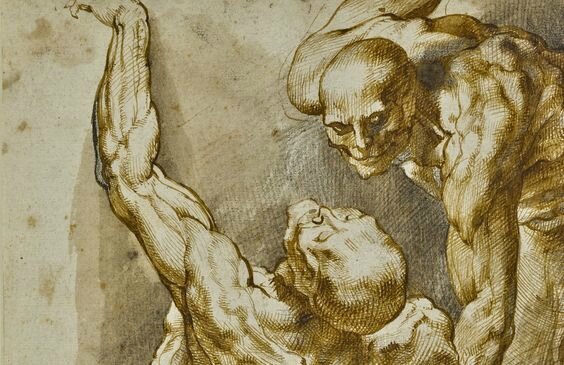

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen 1577 - 1640 Antwerp), Anatomical studies of three male figures

Lot 2831, Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen 1577 - 1640 Antwerp), Anatomical studies of three male figures. Pen and brown ink and wash and black chalk, 291 by 191 mm, 11 1/2 by 7 1/2 in. Estimate 4,000,000 — 6,000,000 HKD (463,181 - 694,771 EUR). Photo Sotheby's.

Provenance: Dr. Ludwig Burchard, by whose descendants sold, Christie's London, 6th July 1999, lot 223.

Exhibited: London, National Gallery, Rubens: A Master in the Making, 2005-6, cat. no. 37

Literature: F. Scholten, Willem van Tetrode, Sculptor (c.1525-1580), exhib. cat., Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, and New York, Frick Collection, 2003, p. 72, reproduced fig. 92.

A.-M. Logan and M.C. Plomp, Peter Paul Rubens, The Drawings, exhib. cat., New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005, pp. 98, 100 note 2, under no. 16.

D. Laurenza, 'Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy, Images from a Scientific Revolution,' The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, LXIX, no. 3 (Winter 2012), p. 44, fig. 65.

Note: Engraved:

1. In reverse by Paulus Pontius (fig. 1).1

2. By Willem Panneels

Fig. 1: Paulus Pontius, Anatomical studies of three male figures after Rubens, engraving

This important, early drawing by Rubens is perhaps the most powerful and dramatic of a group of some fourteen anatomical drawings, which the artist is thought to have made with the intention of having them engraved as illustrations to an anatomy book. Roughly half of the drawings in the series are écorché studies of one or more figures in similarly tortured poses, while the remainder are studies of limbs, or other partial figure studies. The majority of the drawings is executed in pen and brown ink, sometimes also with the addition of a little brown wash, but in one or two cases Rubens has, as here, further enriched the visual effect by combining these media with chalk, either red or black.

Scholars agree that Rubens made these fascinating, powerful drawings during the first decade of the 17th century, although Michael Jaffé thought they date from the latter part of this time bracket (1605-1610), while Jeffrey Muller and Anne-Marie Logan feel they are somewhat earlier.2 Logan suggests that they were probably executed during the artist’s initial years in Mantua, 1600-1605, and that he may have been inspired to create these works by seeing a series of anatomical studies by Leonardo da Vinci, which Roger de Piles tells us greatly impressed the young Rubens. It is likely that the Leonardo anatomical drawings that Rubens saw were those in the possession of the sculptor Pompeo Leoni, in Madrid, which he would have had the opportunity to study in 1603, when he travelled to Madrid at the request of the Duke of Mantua.

Another possible source of inspiration, particularly for the present sheet, is the work of the highly original 16th-century Dutch sculptor Willem van Tetrode (c. 1525-1580), who made an écorché bronze of a man (fig. 2)3 that is in many respects very similar in character to the dynamic, full-figure drawings from within the group of Rubens’s anatomy studies.

Fig. 2: Willem van Tetrode, A bronze écorché figure of a man, Private Collection

Until relatively recently, the existence of a series of anatomical drawings of this type by Rubens was only known from a series of engraved and drawn copies of these works. The earliest of those seem to be the prints, in reverse, made by Paulus Pontius, and published after Rubens’s death in 1640 by Alexander Voet in Antwerp. Many of the Rubens originals are also recorded in drawings, mostly now in Copenhagen, chiefly executed by Rubens’s student Willem Panneels (c. 1600-1634), who is known to have resided in the master’s house while Rubens himself was away during 1628 and 1629. Some of these copies by Panneels bear inscriptions noting that the drawing in question was copied after originals in Rubens’s “annotomibock;” a copy after the large central figure in the present drawing is inscribed: “oockalvant cantoorvanrubbens” (“also from Rubens’s cantoor [i.e. office]”).4 Panneels also made prints after the drawings, in the same direction as the originals. Yet although the images were thus well known, the original drawings by Rubens have only themselves come to light relatively recently. Eleven of the drawings were unknown until they appeared on the market in 1987, offered for sale by descendants of Sir Robert Newdegate, 5th Bart., who appears to have acquired them while on the Grand Tour, in 1738-40.5 The present drawing, formerly in the collection of the great Rubens scholar Ludwig Burchard, was added to the group in 1999, and others that can plausibly be associated with these twelve are at Chatsworth, in the Albertina, and formerly at the Martin Bodmer Foundation, Geneva.6

A further copy after the present drawing, this time recording the entire composition, was sold at Sotheby’s in London, 29th June 1926 (lot 115, as after Michelangelo’s Last Judgement). That drawing may possibly have been made by Pontius, who would very likely have made his own copies of the Rubens drawings that he intended to engrave, so as to avoid damaging the originals by indenting the outlines with the stylus, a necessary part of the print-making process. A copy of another drawing from the series, now in the Wellcome Library, London, has also been attributed by Logan to Pontius. The copy sold in 1926 bears the numbering of the great French collector Pierre Crozat, and this may provide the clue to a rather uncomplimentary comment made by Pierre-Jean Mariette: ‘M. Crozat a quelques uns de ces desseins de figures ecorchées, qui sont beaux, mais peu interessans.’7 If the drawings that Mariette saw in Crozat’s collection were copies of the quality of the one attributed to Pontius, it is not surprising he was so dismissive.

Though it is rather more pictorial and compositionally complete than most of the other drawings in the series,8 this fine sheet of studies certainly belongs to the group: the paper shares the same watermark found in three of the sheets sold in 19879, and the combination of pen and ink with chalk hatching is also found in at least one of the Newdegate drawings.10 Together, these extraordinary anatomical studies by Rubens illustrate an otherwise little known but highly intriguing aspect of the artist’s work, and also demonstrate his astonishing ability to transform what could have been a somewhat academic, even dry, project into an opportunity to explore the extraordinary visual potential offered by the poses, forms and surfaces of these remarkable figures.

1 See J.M. Muller, ‘Rubens’ Anatomy Book’ in Rubens Cantoor, een verzameling tekeningen ontstaan in Rubens' atelier, exhib. cat., Antwerp, Rubenshuis, 1983, pp. 102-103, no. 18A.

2 Logan, loc.cit.

3 c. 1562-67, the Hearn Family Trust, New York; see Scholten, op.cit., p. 125, no. 31.

4 Rubens Cantoor, p. 102, no. 17.

5 Sale, London, Christie’s, 6th/7th July 1987, lots 57-67, with introduction by Michael Jaffé.

6 Respectively: Chatsworth, no. 1200, M. Jaffé, The Devonshire Collection of Northern European Drawings,Turin/London/Venice 2002, vol. I, no. 1133; idem, Van Dyck's Antwerp Sketchbook, London 1966, pp. 100-2, pl. XLIV; sale, New York, Christie's, 26th January 2002, lot 153.

7 Jaffé, op.cit., 1987, p. 58.

8 It should be noted the Dr. Anne-Marie Logan has suggested, orally, that some or all of the grey wash in the present drawing may have been added, perhaps by Pontius, in preparation for the execution of his print.

9 Sale, London, Christie’s, 6th/7th July 1987, lots 62, 64 and 67.

10 Idem, lot 58.

Sotheby's. Literati / Curiosity II, Hong Kong, 05 Apr 2016, 10:15 AM

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F23%2F119589%2F128179837_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F91%2F05%2F119589%2F127218856_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F19%2F119589%2F120673279_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F85%2F03%2F119589%2F120567566_o.jpg)