Basquiat sets artist record at Christie's New York sale at $57.3 million

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Untitled (detail), acrylic on canvas, Painted in 1982. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

NEW YORK, NY.- The May 10 evening sale of Post-War and Contemporary Art realized US$318,388,000 / £220,796,117 /€279,086,291 with sell-through rates of 87% by lot and 91% by value. The sale established 6 new world auction records for artists including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Agnes Martin, Mike Kelley, Richard Prince, Kerry James Marshall and Barry X Ball. The results of tonight’s sale brings the week’s running total to $396.5million, which includes the price achieved by the May 8 evening auction of Bound to Fail.

The sale attracted registered bidders from 39 countries, with strong bidding from Asia, Europe and the United States.

Sara Friedlander, Vice President, Head of Evening Sale, Post-War and Contemporary Art, stated: “We built our sales this season to reflect the macro environment, providing an ideal balance that suits an array of collecting tastes. Tonight’s success is the result of a tightly edited sale with top quality works, which were extremely fresh to the marketplace. 84% of the lots had never been sold at auction, and of the 10 works that had been sold, only 4 had been offered over the past 10 years. We are very pleased to see collectors gravitate to a broad spectrum of art, spanning from masterpiece quality works, including Rothko’s No. 17, to artists who are quickly rising within the auction market. One such example is Kerry James Marshall, whose Plunge, captivated the imagination of so many collectors and set a world auction record for the artist.”

Brett Gorvy, Chairman and International Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art, remarked: “We are very proud of the record price achieved for Basquiat’s monumental portrait of the artist as devil at a time when top collectors are pursuing works of the very highest quality. This painting drew intense competition that dispelled questions of a market contraction. We are particularly happy that the work was acquired by a collector in Asia, demonstrating the global scope of the masterpiece market".

Lot 36. Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Untitled, signed and dated 'Jean-Michel Basquiat Modena 82' (on the reverse), acrylic on canvas, 94 x 197 in. (238.7 x 500.4 cm). Painted in 1982. Estimate on Request. Price Realized $57,285,000. World auction record. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Provenance: Annina Nosei Gallery, New York

Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya

Enrico Navarra Gallery, New York

Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong

Private collection, New York

Anon. sale; Sotheby's, London, 23 June 2004, lot 32

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: R. Marshall and J. L. Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris, Galerie Enrico Navarra, 1996, v. I, pp. 56-57 and cover (illustrated in color); v. II, pp. 76-77 (illustrated in color).

T. Shafrazi, J. Deitch and R. Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, Tony Shafrazi Gallery, 1999, pp. 110-111 (illustrated in color).

E. Navarra, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris and New York, 2000, v. I, pp. 72-73 (illustrated in color); v. II, p. 98, no. 2 (illustrated in color).

E. Navarra, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris and New York, 2010, v. I, pp. 72-73 (illustrated in color); v. II, p. 98, no. 2 (illustrated in color).

A. Lindemann, Collecting Contemporary Art, Cologne, 2013, p. 129 (illustrated in color).

Exhibited: R. Marshall and J. L. Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris, Galerie Enrico Navarra, 1996, v. I, pp. 56-57 and cover (illustrated in color); v. II, pp. 76-77 (illustrated in color).

T. Shafrazi, J. Deitch and R. Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, Tony Shafrazi Gallery, 1999, pp. 110-111 (illustrated in color).

E. Navarra, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris and New York, 2000, v. I, pp. 72-73 (illustrated in color); v. II, p. 98, no. 2 (illustrated in color).

E. Navarra, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris and New York, 2010, v. I, pp. 72-73 (illustrated in color); v. II, p. 98, no. 2 (illustrated in color).

A. Lindemann, Collecting Contemporary Art, Cologne, 2013, p. 129 (illustrated in color).

Notes: Painted in 1982, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled is an epic painting, its monumental size and visceral painterly energy marking it out as one of the artist’s most accomplished works. Measuring more than sixteen feet wide and nearly eight feet tall, it is also one of the artist’s largest canvases, yet it is the dynamism with which Basquiat constructs his painterly surface that distinguishes this work, especially considering it was painted when the artist was only 22 years old. The full force of his painterly energy can be witnessed across every inch of this vast canvas; from the lavishly fashioned demonic figure that occupies the central portion of the canvas, to his extensive repertoire of painterly drips, splashes and impulsive brushwork, the surface of Untitled acts as a totem to Basquiat’s capricious talent. Painted during his trip to Modena in Italy, Untitled belongs to a significant group of paintings that helped to forge his reputation as one of the most exciting and radical artists of his generation.

Dominating the canvas is a dramatic figure; a heroic self-portrait with Basquiat depicting himself as a devil rising amidst an explosion of expressive gestures. The horned figure commands the composition, standing as he does with his limbs outstretched almost touching either side of the canvas. Although most of his body is left to Basquiat’s imagination (save for the three broad sweeps of black paint that define his ribcage); it is Basquiat’s face which displays the full force of the artist’s painterly prowess. Crowned by a pair of dramatic horns, the grinning face portrays a threatening menace. Piercing eyes stare out from the surface of the canvas, built up from consecutive layers of orange, red, white and black paint. Harried circles made by the movement of Basquiat’s brush contain deep pools of pigment as he lays down multiple layers of red, followed by white before finally topping it off by accentuating highlights of black. The result engages the viewer with an almost hypnotic feeling of entrapment, pulling them in with the devil’s spellbinding stare. The rest of the facial features are constructed in this same fashion, resulting in a strong, wide nose and wild, grimacing teeth. In contrast to the precise definition of the devil figure, across the rest of the canvas, Basquiat orchestrates a flurry of loose drips, daubs, and splashes of paint set amidst of expressionistic brushstrokes. Ranging from broad swaths of muted pinks, yellows, reds and blues to streaks of explosive reds and neon greens that appear to have been thrown directly at the surface of the canvas, the result is an active surface which displays the full richness of Basquiat’s painterly repertoire. Thus, Untitled becomes a stage upon which the artist unleashes an exorcism of creativity across its surface.

This is the largest in a series of paintings which Basquiat undertook during two periods he spent in Modena, Italy, in the spring of 1981 and 1982. He was initially invited to Europe by Emilio Mazzoli to participate in his first ever one-man show after the dealer saw the artist’s work in January 1981 at the legendary New York/New Wave show at New York’s P.S. 1. After the initial trip he returned again in March 1982 and it was during this stay that he painted Untitled and a sister painting Profit 1, which are widely considered to be among the artist’s most important paintings. The contrast between the divine figure in Profit 1, bedecked in a bright red shirt and sporting a large glowing halo, and the dark, ominous background against which he is silhouetted make this painting one of the most powerful and poignant of the artist’s career. The dichotomy between heaven and hell can also be seen in Untitled, except here the sentiment is flipped in that that the horned figure of the devil is situated in a vibrant multicolored backdrop, far removed from the menacing nature of his being.

With paintings such as the present work, Basquiat follows in a noble tradition of 20th century artists who channeled their creative energy into producing groundbreaking canvases. Basquiat was a remarkably erudite scholar of art history and from a young age would spend time in the museums of New York teaching himself about, and admiring the work of, the great painters from the art historical canon. He particularly admired such luminaries as Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock and Cy Twombly. He was an ardent admirer of Picasso, from whom he gained the confidence to allow himself to be liberated from the concords of conventional painting. He admired his epic sense of scale and rapid deployment of paint onto the canvas surface. He also admired the way in which the Spanish artist constructed his figures, particularly how he rejected the need to depict the subtle nuances of the human face, instead focusing only on the most powerful features. As curator Richard Marshall explained, “Picasso’s work gave Basquiat the authority and the art historical precedent to pursue his own brash and aggressive portraits…” (R. Marshall, “Repelling Ghosts,” in R. Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1993, p. 16).

The active surface of Untitled, with its liquescent application of paint, evokes the fluid composition of Jackson Pollock’s large-scale paintings such as Lucifer, 1947 (The Anderson Collection at Stanford University). Pollock, who like Basquiat often unleashed his creativity on a grand scale, once proclaimed that “Painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through” (J. Pollock, quoted by quoted by Kirk Varnedoe, Jackson Pollock, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1998, p. 48). Just like Basquiat, Pollock embraced the notion of chance in his paintings and while he carefully introduced the liquid canvas to the surface, he was prepared to let the laws and physics of gravity dictate the final path of the journey the paint would take across its surface. As can be witnessed in Untitled, just as Pollock embraced the physical nature of his medium to dictate much of the finished look of his dripped and poured paintings, Basquiat whole-heartedly embraced the liquid qualities of the paint to define many of the compositional aspects of his painting.

Basquiat’s central figure in Untitled also recalls, formally at least, the work of another early 20th century modernist, Max Ernst. The tall, vertical figures that populate the German painter’s canvases and sculptures bear some of the same totemic formalism as Basquiat’s figures—the example in Untitled being particularly noticeable. Like Basquiat, whose inspiration is rooted in the myths and folklore of his Puerto Rican/Haitian heritage, Ernst’s formal inspiration was indebted to his interested in the folklore of the Native American peoples of the Southwest Plains. Ernst’s move to Arizona in the 1940s caused an influx of mythological forms to enter into his work, much of which was inspired by his new neighbors, the Hopi, Navaho and Apache Indians. The following description of Ernst’s work from this period also seems remarkably appropriate to Basquiat’s work too. “…he never tried to capture the appearance of the human being… Throughout his [Ernst’s] work, man is represented by some substitute, either imaginary form, or a mark…by a schematized figure whose head may be a rectangle, a triangle or a disk. In a similar manner, the Indians used geometric forms in their paintings, figurines and masks. Here the head may be a circle, there a square and elsewhere a triangle… Thus forms do not represent appearances, but ideas” (P. Waldberg, quoted by K. Varnadoe, Primitivism In 20th Century Art, vol. II, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1984, pp. 564-65).

1982 was a marquee year for Basquiat as it saw him continue his meteoric rise within the New York art world as he was rewarded with his first solo show at Annina Nosei’s gallery. He also made an important trip to Los Angeles where he was introduced to—and proved to be a major hit with—influential collectors such as Eli and Edythe Broad, Douglas S. Cramer and Stephane Janssen. He was also the youngest of 176 artists to be invited to take part in Documenta 7 in Germany where the expressive nature of lyrical lines was compared to that of the other master draughtsman of the post-war period, Cy Twombly. This comparison to Twombly must have been particularly rewarding for Basquiat as he was the only artist whom Basquiat acknowledged publically as being influential to his career, as Marshall explains, “From Cy Twombly, Basquiat also took license and instruction on how to draw, scribble, write, collage, and paint simultaneously. One of the few art artworks that Basquiat ever cited as an influence was Twombly’s Apollo and the Artist (1975), and its impact is apparent in numerous loose, collaged and scribbled Basquiat works…” (R. Marshall, “Repelling Ghosts,” in R. Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1993, p. 16).

Indeed, Basquiat’s work found favor with many influential critics who had yearned for the return of “the expressive” ever since the triumph of Minimalism in the late 1960s and 1970s. In Basquiat they found a new champion who clearly reveled in the joy of the artist’s hand. “What has propelled him so quickly,” extolled Lisa Liebmann in her Art in America review of Basquiat’s 1982 exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery, “is the unmistakable eloquence of his touch. The linear quality of his phrases and notations…shows innate subtlety—he gives us not gestural indulgence, but an intimately calibrated relationship to surface instead” (L. Liebmann, quoted in M. Franklin Sirmans, “Chronology,” in R. Marshall (ed.), Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1992, p. 239).

Almost always autobiographical in some way, Basquiat’s paintings are pervaded with the sense that the artist was talking to himself, exorcising creative demons, exposing uncomfortable truths and trying to explain the way of things to himself—an effort that became increasingly pronounced at this time. Executed in vivacious colors over a background of complex painterly layers and bold architectonic elements, this dramatic and iconic portrait is both a forceful and an aggressive presence, whose impressive postures and dramatic features are expressive of the artist’s own fears and anxieties. When questioned about his method of constructing an image, Basquiat would go on to confirm, “I don’t think about art when I’m working. I try to think about life” (J. M. Basquiat, quoted in Basquiat, exh. cat., Trieste, Museo Revoltella, 1999, p. LXVII).

Lot 17. Mark Rothko (1903-1970), No. 17, oil on canvas, 91 1/2 x 69 1/2 in. (232.5 x 176.5 cm). Painted in 1957. Estimate $30,000,000 - $40,000,000. Price Realized $32,645,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Provenance: Galerie Beyeler, Basel

Private collection, Italy

Sotheby's Private Sales, New York

Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Exhibited: London, Whitechapel Art Gallery; Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum; Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles; Kunsthalle Basel; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna and Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Mark Rothko: A Retrospective Exhibition, Paintings 1945–1960, October 1961-January 1963, no. 31 (London; illustrated); no. 31 (Amsterdam); no. 31 (Brussels); no. 32 (Basel); no. 32 (Rome; illustrated); no. 27 (Paris).

Riehen/Basel, Fondation Beyeler, Mark Rothko: a Consummated Experience between Picture and Onlooker,February-April 2001, pp. 117 and 173, no. 35 (illustrated in color).

Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Mark Rothko, October 2007-January 2008, pp. 63, 150-151 and 198, fig. 46, no. 67 (illustrated in color).

Notes: Mark Rothko’s No. 17 is a dazzling manifestation of the painterly tussles which the artist played out across the surface of his canvases. Painted in 1957, its vibrant, verdant hues are emblematic of the experiential nature of Rothko’s art—a manifestation of what one critic called the “immediate radiance” of the paintings from this period of the artist’s career. Exhibited at Rothko’s seminal exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1961 (one of the artist’s first solo shows in Europe), this painting spent several decades out of the public realm in a private European collection before making a triumphal appearance in 2001 when it was publically exhibited for the first time in over 30 years. A central part of an exhibition of Rothko’s paintings organized by the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, No. 17 becomes an important work in the canon of Rothko’s paintings from the mid-1950s. Produced at the dawn of his mature period, and just a short time before he embarked on what would become his magnum opus, the Seagram Murals, this painting encapsulates all of the drama and psychological intensity of an artist who became one of the most celebrated and influential artists of the twentieth century.

Across the surface of this large painting, Rothko lays down a multitude of diaphanous veils of color, which results in a series of chromatic veneers of luxuriant blues and verdant greens. Rothko’s chromatic field is segmented into three passages that appear to hover gracefully on top of a sea of cobalt blue—a body of color which gradually shifts in intensity from deep hues along the upper edges to more muted tones as the eye journeys down the picture plane. A large square of lush green sits on top of a smaller, yet seemingly more solid passage of royal blue. Sandwiched between both these blocks is a strip of high-keyed azure blue, the active edges of this thin strip increasing their impact by bleeding into the neighboring areas with intoxicating results. Rothko always insisted that it was here, where the edges of his painterly passages meet, that the true essence of his paintings could be witnessed.

Rothko’s surfaces are rich in the subtle nuances of his painterly practice. In No. 17 the traces of the many layers that the artist lays down can be seen in the softly undulating layers of underpainting that constantly bubble up towards the surface. These surging strata result in a delicate shifting of color, as areas of darker pigment give way to saturated passages of high-keyed intensity. This sensation is also enhanced by Rothko’s use of both matte and gloss paints and this very specific method of paint application helps to capture the sense of drama that Rothko wished to convey with his mature paintings. It was Hubert Crehan, in one of the first reviews of the artist’s paintings from this period, who wrote about the “immediate radiance” of Rothko’s paintings. “We have in our time become aware of the reports of the great billows of colored light that have ripped asunder the calm skies over the atolls of the calmest ocean. We have heard of the terrible beauty of that light, a light softer, more pacifying than the hues of a rainbow and yet detonated as from some wrathful and diabolical depth. The tension of the color-relationships of some of the Rothko paintings I have seen has been raised to such a shrill pitch that one begins to feel in them that a fission might happen, that they might detonate” (H. Crehan, “Rothko’s Wall of Light: A Show of His New Works at Chicago,” Arts Digest 29, November 1, 1954, p. 19).

Although Rothko never acknowledged himself as a colorist, the chromatic intensity of No. 17 clearly demonstrates his innate understanding of the power of color. In 1961, Robert Goldwater, whom the artist acknowledged was one of the few critics who actually understood his work, wrote “Rothko claims that he is ‘no colorist,’ and that if we regard him as such we miss the point to his art. Yet it is hardly a secret that color is his sole medium… Rothko’s concern over the years has been the reduction of his vehicle to the unique colored surface which represents nothing and supports nothing else” (R. Goldwater, quoted by J. Gage, “Rothko: Color as Subject,” in J. Weiss, Mark Rothko, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1998, p. 247). Even Duncan Phillips, one of the artist’s greatest patrons who arranged a handful of paintings in “a little chapel for meditation” at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., acknowledged that it was Rothko’s natural affinity with color that marked out his greatness (Ibid., pp. 247-248). Rothko was adamant, though, and continued to insist that it was not color per se that was instrumental to his work, more it was a vehicle which helped him to achieve what he was really trying to accomplish, that of initiating an intensely, innately emotional reaction when one stood before his work.

No. 17 was produced at the height of Rothko’s painterly powers. One of the artist’s rare “blue” canvases, this work belongs to a select group that marked the culmination of a short period during which he executed a number of brightly hued works and just a few months before he embarked on a series of paintings that have become widely regarded as the pinnacle of his career, the Seagram Murals (Tate Gallery, London). While Rothko’s choice of colors should never be considered in any figurative sense, the artist’s upbeat mood during this period might have contributed in some way to their vibrant hues. In a letter to Herbert Ferber written in March 1957, Rothko wrote of his positivity following a spring trip to New Orleans, “We have been ensconced in a suburb called Metairie, which is an exact equivalent of plush Westchester. We have a house, a garden of proportions, manicured lawns and manicured neighbors… We have been fortunate enough with the weather. There have been a number of benign days of early summer, sun, warmth and lush growth” (M. Rothko, quoted by M. López-Remiro (ed.), Writings on Art: Mark Rothko, New Haven, 2006, p. 121). However, Rothko was always at pains to explain that his paintings were not paintings of an experience—they were the experience. In 1956 he wrote, “I am only interested in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on—and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures show that I communicatethose basic human emotions… The people who weep before my paintings are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!” (M. Rothko, quoted by M. López-Remiro (ed.), Writings on Art: Mark Rothko, New Haven, 2006, pp. 119-120).

This painting was exhibited in a retrospective of Rothko’s work organized by the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York which travelled widely throughout Europe beginning at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1961, and traveled to Amsterdam, Brussels, Basel, Rome before finishing at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in January 1963. This major exhibition not only championed the cause of Abstract Expressionism across Europe but it also confirmed Rothko’s status as one of its vanguards. Visitors to the exhibition described their reaction to the artist’s paintings as “Shocked… Spellbound… Transformed (quoted in “How Rothko Won Over Britain,”Huffington Post, February 2, 2012 via http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mutualart/mark-rothko-whitechapel-exhibit [accessed March 23, 2016]) and a current curator at the Whitechapel, Nayai Yiakoumaki, called this exhibition one of the artist’s most significant. “This exhibition is very important because it introduced his work to the British public for the first time, in such a large volume and a public gallery… [From] this exhibition on, the art world was captivated by Rothko and subsequently, [Tate Director] Norman Reid, approached the artist to discuss a purchase of works…culminating with the substantial donation of eight of the Seagram Murals to the Tate in 1970” (N. Yiakoumaki, ibid.).

Between 1961 and 2001, No. 17 (also in the past known as Green on Blue on Blue) was part of a private Italian collection and its exhibition in Basel was the first time the work had been on public display for nearly thirty years. It is perhaps fitting that a painting such as the present example should reside for so long in Italy, a country with which Rothko had such a particular personal and professional affinity. Rothko made three visits to the country during his lifetime, beginning in 1950, then again in 1959 with the final trip being made in 1966, after which he reminisced, “The memory of Italy is glorious” (M. Rothko, quoted by G. Carandente, “Mark Rothko’s Three Italian Journeys,” in Rothko,exh. cat., Palazzo delle Esposizini, 2008, p. 33). During their visits, Rothko and his family travelled extensively throughout the country and met a number of collectors, critics and curators who would become loyal supporters of his work including Peggy Guggenheim and Carla Panicali, then director of the Rome branch of the Marlborough Gallery. His travels led him to witness for himself the magnificent mosaics of the Last Judgment in Torcello, and the splendors of Florence, Siena and Arezzo. Never one for hyperbole, Rothko was nonetheless moved by his visits to the country telling students at the Pratt Institute in 1958 that “When I went to Europe and saw the Old Masters, I was involved with the credibility of the drama. ...My current pictures are involved with the scale of human feelings the human drama, as much of it as I can express” (M. López-Remiro, op. cit., p. 124).

Just as Rothko fell in love with Italy, many Italian collectors and critics fell in love with Rothko. The artist’s work was first shown in the country as part of the 1948 Venice Biennale, but it wasn’t until the 1958 Biennale that his work caused such a stir. For the exhibition, the art historian Sam Hunter selected ten paintings from 1957-1958 to be hung in the American Pavilion, resulting in what he considered to be an almost “transcendental experience” (S. Hunter, quoted by C. Terenzi, “Rothko: Exhibitions and Critical Reception in Italy,” in Rothko, exh. cat., Palazzo delle Esposizini, 2008, p. 57). Perhaps because their minds were not as contaminated by the dominance of Abstract Expressionism, Rothko felt the Italian critics were more attuned to what he was trying to accomplish with his paintings. He received what he regarded to be some of the most perceptive reviews of his work for the paintings that were displayed in Venice. Among them was this insightful notice by Gillo Dorfles who opined, “Thus we no longer have red and blue from a tube, or merely their ‘sign’ value, but we will have the entity of red or the entity of blue, in whose universe we shall feel exalted or inhibited, numb or excited…” (G. Dorfles, quoted by C. Terenzi, ibid.). Another particularly perceptive observation was made by the noted critic Luciano Pistoli, who said that “The outlines of the visitors in front of Rothko’s works are blurred by the luminous signals that these paintings transmit to each other. Here our eyes perceive a malaise that is actually dizzying” (Ibid.). As Terenzi notes, “Pistoli not only grasps the dramatic quality of Rothko’s work, but also the suggestion of oneness and, at the same time, of interference, in his works” (Terenzi, op cit., p. 60).

Due to its rare, lush palette and grand scale, No. 17 seems to encompass the vastness and drama of Rothko’s universe. The power, potency and depth of these elements are echoed through the gravitas of the swift but also light brushstrokes that he used to make the painting’s radiant and shimmering surface. Seeming to express an inexplicable but also overwhelming human experience, a painting like this nonetheless illustrates the emotive power of pure color to articulate a deep and innate human language. It is a work that responds to the demand that Rothko first asserted in 1948 when he wrote that “Pictures must be miraculous...a revelation, an unexpected and unprecedented resolution of an eternally familiar need” (M. Rothko, “The Romantics Were Prompted,” Possibilities, No. 1, Winter 1947/8).

Lot 28. Clyfford Still (1904-1980), PH-234, signed 'Still' (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 69 x 59 5/8 in. (175.3 x 151.4 cm). Painted in 1948. Estimate $25,000,000 - $35,000,000. Price Realized $28,165,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Provenance: E.J. Power, London, acquired directly from the artist, 1957

Private collection, United States, acquired from the Estate of the above, 1993

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 2004

Literature: Brancusi to Beuys, Works from the Ted Power Collection, exh. cat., London, Tate Gallery, 1996, pp. 16-17, fig. 5 (illustrated in color).

Exhibited: London, Institute of Contemporary Arts, Some Paintings from the E.J. Power Collection, March-April 1958, no. 9 (illustrated).

Washington, D.C., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Clyfford Still: Paintings, 1944-1960, June-September 2001, no. 15 (illustrated in color).

Notes: The richly textured surface and chromatic intensity of Clyfford Still’s PH-234 is a superlative example of the almost primeval energy which the artist was able to commit to canvas and which led him to become one of the most important and influential painters of his generation. A major figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement, perhaps more than any other member of that group Still embodied the rejection of figuration and sort to demonstrate the visceral energy possessed by the combination of pure pigment and the emotive power of the gesture. Across its expansive surfaceUntitled unveils the complexity of Still’s oeuvre as he brings together divergent areas of color, creating a palpable sense of tension as large sea of deep blue tussles for supremacy with subtle passages of lighter pigment as a vertical expanse of scorching red, spreads across the surface like a trail of molten lava.

Clyfford Still’s reputation as one of the giants of Abstract Expressionism is built upon this mastery of the painterly process. Unlike some of his contemporaries, whose expressive yet simple gestures dominated the canvas, Still builds up his richly textured surface by putting down layer upon layer of coarse pigment. In PH-234 this can most clearly be seen in the large region of dark blue which dominates much of the central and left hand portions of the canvas. Here, what at first glance appears to be an expanse of monochromality, is in fact an essay on the rich and almost limitless possibilities of color. By building up uneven layers of color, some more dense and vibrant that others, Still produces a surface that appears to constantly shift in tone and intensity as the eye meanders across its decadent surface. The primordial nature of Still’s paintings is further enhanced by the dramatic fissures which he opens up across the surface of many of his works. Here, we can see evidence of this in a number of places, most ominously in the right portion of the canvas as Still creates a fracture of red paint that sits amid neighboring passages of dark blacks and grays.

In addition to the maturity of the subject matter, this painting also demonstrates the rich variety of Still’s painting technique. Despite the clear separation of light and dark tones, Still continually works the entire surface of his canvas, laying numerous layers of paint and scrapping them off to show the colors underneath. The edges where the forms meet are always a high point in his work, and in this painting the areas of high contrast superbly demonstrate the sublime way in which Still handles these areas. The jagged forms that cut into each other are accentuated by creating “halos” of delicately contrasting light tones that serve to allow the brown internal forms to recede into the inky darkness whilst allowing the black tones to reinstate their intensity. These spatial relationships are what Still does best and are what set him apart from his contemporaries such as Pollock and Rothko. Works such as the present example, clearly demonstrate the power of these spatial associations to impress upon the viewer the essence of Still’s awe-inspiring oeuvre. As Robert Hughes stated, “virtually no modernist paintings done before 1945 look like his” (R. Hughes, The Shock of the New, New York, 1987, p. 316).

This painting was produced during the period immediately after Still’s first great solo exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery in February 1946. In the introduction to the exhibition Still’s then friend Mark Rothko related Still’s new art to the epic and transcendent dimension of “Myth” and explained how Still, “working out West, and alone,” had, with “unprecedented forms and completely personal methods,” arrived at a completely new way of painting. The simple, seemingly organic forms of Still’s painting and its bold expansive fields of space and color made “the rest of us look academic” Jackson Pollock observed at the time. For Rothko, the new vision offered by Still’s apparently completely abstract paintings, not only took the lead amongst this generation of artists, but invoked a fundamental human truth, one that expressed “the tragic-religious drama...generic to all Myths at all times,” and created “new counterparts to replace the old mythological hybrids” which had lost their pertinence in the intervening centuries. (M. Rothko, “Introduction to First Exhibition Paintings: Clyfford Still,” 1946, reproduced in M. Lopez-Remiro, ed., Mark Rothko: Writings on Art, New Haven, 2006, p. 48).

Still insisted that on every level his work dealt with the fundamental questions of what it was to be human. His upbringing on the Canadian Prairies and in the remote northern plains of America instilled in him a respect for the space and silence that was becoming increasingly hard to find in the industrial world. During the 1930s Still also spent time on the Colville Native American Indian Reservation where he helped to found the Nespelem Art Colony. He admired the Native Americans’ ancient and mystical relationship with the land and this helped permeate his art with the highly-developed sense of spatial awareness that is unique to his canvasses. However, he resisted the urge to qualify his works as landscapes; he famously remarked, “The fact that I grew up on the prairies has nothing to do with my paintings, with what people think they find in them” because ultimately “I paint myself, not nature” (C. Still, Paintings by Clyfford Still, exh. cat., Buffalo, 1959, n.p.). Still’s own self-image of his art and his life was that of an elemental and solitary journey through the landscape of nature. Indeed, he described the evolution of his mature style of painting in the mid-1940s and the freedom it ultimately gave him as “a journey that one must make, walking straight and alone. No respite or short-cuts were permitted. And one’s will had to hold against every challenge of triumph, or failure, or the praise of Vanity Fair. Until one had crossed the darkened and wasted valleys and come at last into clear air and could stand on a high and limitless plain. Imagination, no longer fettered by the laws of fear, became as one with Vision. And the Act, intrinsic and absolute, was its meaning, and the bearer of its passion” (Ibid.).

PH-234 was originally owned by Ted Power, one of the great collectors of international postwar art. Beginning in the mid-1950s, Power sought out the newest and most radical art he could find. He taught himself to discern what moved him and refined his eye to search for quality works by artists such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman. He acquired PH-234 in January 1957 after becoming enthralled with the work of the Abstract Expressionists at the important exhibition of new American art organized by the Tate Gallery in London. “To me,” Power explained, “one of the most fascinating aspects of a painting which I like is that it is a unique expression or statement of the artist’s ideas and emotions communicated through colour, shape, and texture, by him to me, in a form which I can hold, keep, and own, and live with, and enjoy, and perhaps with time get to know and understand. This knowing of a picture should always be a challenge” (E. Power, quoted By J. Mundy, “The Challenge of Post-War Art: The Collection of Ted Power,” in J. Mundy, Brancusi to Beuys: Works from the Ted Power Collection, exh. cat., Tate Gallery, London, 1996, p. 10).

Perhaps more than any other artist Clyfford Still was reluctant to show or sell any of his works. In his lifetime he had only 15 solo exhibitions over a period of 45 years, and of these only five were at private galleries where patrons were able to acquire the works. Today, his work can be seen in many major museums including 30 paintings in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 12 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the largest collection of the artist’s work at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver. Still is now one of the most widely respected of the Abstract Expressionist artists, and along with Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, his works stand as examples of the revolutionary paintings produced during a period that changed the course of art history.

It is perhaps testament to Still’s art that, despite his eschewing of the growing commerciality of the art world, his work became among some of the most powerful and important paintings produced in the latter part of the twentieth century. It represents the pinnacle of Abstract Expressionism—a pure form of painting that relies solely on its creator to express the power and intense visceral nature of its form. The making of the painting was itself romanticized into an almost mystical journey through the apparent void of existence, a journey that in the end provided and revealed its own meaning. It was in this way that Still could equate his work with the timelessness and the elemental. His best works have an inherent power that is perhaps best summed up by Still himself, who in a rare moment of retrospection characterized the fundamental raison d’etre of his work when he concluded, “You can turn the lights out. The paintings will carry their own fire” (C. Still, quoted in M. Auping, Clyfford Still, exh. cat., Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 2002, p. 303). This painting carries this fire to its very core.

Christopher Wool (B. 1955), And If You, signed, titled and dated 'And If You Wool 1992' (on the reverse), enamel on aluminum, 108 x 72 in. (274.3 x 182.9 cm). Painted in 1992. Estimate $12,000,000 - $18,000,000. Price Realized $13,605,000. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Provenance: Luhring Augustine, New York

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Notes: The terse, black-and-white text of Christopher Wool’s And If You accosts the viewer with menacing authority, its brutal message rendered in stark capital letters: “AND IF YOU CAN’T TAKE A JOKE YOU CAN GET THE FUCK OUT OF MY HOUSE.” Painted in 1992, And If You belongs to a series of text-based paintings which have become the most iconic of the artist’s oeuvre. The tough-talking jargon of these paintings recalls the brutal one-liners of film noir that goad the viewer with their rough, confrontational style. There is a self-deprecating humor associated with the phrases the artist selected—If You Can’t Take a Joke, Hole in Your Head, Fuck Em If They Can’t Take a Joke—that are obsessively repeated. Taken together, they create an echo chamber in the viewer’s mind not unlike the riotous refrain of a punk anthem. Indeed, And If You depicts a significant phrase that’s repeatedly altered and modified by the artist—like a personal mantra.

And If You is the antidote to the end of painting, the kind of anti-painting that made critics stand up and take notice when the series was exhibited at Luhring Augustine gallery in 1992. One critic commented: “Christopher Wool’s painting is synonymous with major attitude. …While the rancorous flippancy remains darkly adversarial, and the bent of the black-and-white-lettered text is still provocatively industrial and illiterate, the voice has gotten a lot louder and much more combative. …What was once internalized and passively discursive is now an actively abusive and goading address to the viewer: “IF YOU CAN’T TAKE A JOKE, YOU CAN GET THE FUCK OUT OF MY HOUSE” …are phrases obsessively repeated…” (J. Avgikos, “Reviews: Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine” Artforum, vol. 31, no. 5, January 1993, p. 83) Indeed, the rough, jolting effect of Wool’s text-based paintings accost the viewer with their brash, menacing tone. From the time of their first exhibition in 1988 at the 303 Gallery in New York with Robert Gober, their mark on the art world has now become legendary. The curator Richard Flood recalls: “It offered such a simple, reductive solution for moving on that it became a kind of late-eighties mantra.” He goes on: “Wool has kept that edge over the years, slamming down the insults (“IF YOU DON’T LIKE IT YOU CAN GET THE FUCK OUT OF MY HOUSE”)” (R. Flood, “Wool Gathering,” Parkett, vol. 83, September 2008, p. 142).

And If You hounds the viewer with its stark depiction, its legibility creating a kind of “gotcha” moment that results from the terse effectiveness of Wool’s phrase and the stark, graphic quality of its rendering. One critic described: “Orphaned from its brood, a single Wool canvas can elicit a “got it” moment... It is this legibility that lent Wool’s eighties output a kind of immediately iconic, sought after status that has only increased over the years” (F. Meade, “Syntax for Minor Mishaps,” Parkett, vol. 83, September 2008, p. 126) Indeed, this effect is heightened by the materials Wool used for the series, from the terse, no-frills look of the military-issue script to the weighty supremacy of its aluminum support. The painting issues an ultimatum: the “fuck you” of its message is the ultimate statement of rebuke, and the sort of hissed, menacing quality of its message is heightened by the artist’s typeface—a font similar to the one used by the U.S. military after World War II. Wool’s use of such no-frills, utilitarian script lends an aura of “big brother” style authoritarianism, a “do this or else” quality that pervades such signage on the streets of New York like “KEEP OUT” and “POST NO BILLS.” The aluminum panel that Wool uses as his support lends the work an inexorable sense of power and permanence by its weighty, solid and uniform surface. Indeed, aluminum is the stuff of stop signs and highway markers and its indestructible nature retains a sense of government-sponsored regulation and lawfulness. And If Youdisplays a stark sense of authority that issues from these utilitarian materials.

And If You assaults the viewer with the graphic power of its message, yet it also elicits a kind of formal elegance that runs counter to the jarring quality of its text. In rendering the phrase, Wool arranges the letters within a pictorial grid and ignores the conventions of syntax and grammar, allowing the words to run together without regard for visual comprehension. As he described, “I started in the left hand corner and I went like you would with a typewriter” (C. Wool, quoted in “Conversation with Christopher Wool,” with Martin Prinzhorn, Museum in Progress, 1997, via http://www.mip.at/attachments/222 [accessed April 10, 2016]). Indeed, Wool forsakes the conventions of everyday language. When he reaches the end of one line, he simply allows the letters to drop down and continue onto the next regardless of whether the word itself is complete.

By removing grammatical features and eliminating the regular spaces between words, the letters themselves take on a purely abstract quality. The letters are transformed into cyphers, and a complicated back-and-forth between the legible and the illegible results. Condensed, compressed, compacted; Wool’s text is utterly nonsensical until its meaning snaps into place, a split-second effect that’s registered on a subliminal level. Jerry Saltz explained: “The words run together and appear to be some kind of bizarre gibberish...something you can hear but not quite make out. … Confusing at first, [words] suddenly fall into place before the viewer’s eyes. It is just when the viewer finds comfort in deciphering the code that the bottom falls out of the painting and a whole new field of meaning opens up below” (J. Saltz, quoted in “Notes on a Painting,” Arts Magazine, September 1988, p. 20).

What results in And If You is a kind of visual poetry, one that is born out of the particular environment in which it was created. Living and working in New York’s Lower East Side at the beginning of the 1990s, the cacophonous riot of graffiti and the hard-edged nature of the city streets find their expression in this discordant painting. When viewed in a gallery or museum setting, Wool’s gritty, raw incantations are all the more stark and glaring; ripped from the visual fabric of a decaying city, they emanate with rough, brutal force. The critic Greil Marcus writes, “the voices have a quality that falls somewhere between the ranter screaming on the corner...and the person down the block handing out commercial flyers. ... they communicate not like facile appropriations of primitivist street discourse, but as a honed, perfectionist idea of that discourse, reduced to the irreducible and then starting up all over again. The overall impression is of a voice struggling against muteness...or against censorship...in any case against silence”

(G. Marcus, “Wool’s Word Paintings,” Parkett, no. 33, Fall 1992, p. 87).

And If You augurs from that apocryphal postmodern era in which Douglas Crimp’s infamous missive “The End of Painting” declared painting dead, and Wool’s radical canvases validated the genre with a sort of “endgame” visual rhetoric. They issue forth with combative determination and a forceful, belligerent energy that necessitated their survival, and indeed the survival of the entire genre itself. Wool resuscitated painting by suffusing it with the terms of its own survival. His text-based paintings are nihilistic and bombastic, with a bellicose confidence that is gritty and loud. Yet they possess an aura that verges on the sublime, as if they knowingly take up the gauntlet that has been passed to them. “The canonical position that Wool holds in the recent history of art has emerged in light of the renewed interest in the medium of painting. It is not based on his contribution to painting’s ‘endgame’ but rather on his ability to delineate the sites of contestation that keep the discourse around painting open and painting itself alive” (A. Hochdorfer, “Christopher Wool: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,” Artforum, March 2014, p. 281).

At the time Wool’s first text-based paintings emerged in 1987, he had already spent nearly a decade archiving certain words and phrases. After seeing the words “SEX” and “LUV” graffitied in black spray paint on a white truck, he began to stencil words directly onto canvas. These early works display an aggressive, claustrophobic urgency that relates to their origins in the streets of downtown New York. Their historical placement right smack at the beginning of a market meltdown and economic recession make them seem like foreboding harbingers of a brutal destiny. At the time Wool created And If You, he was living in a studio on East 9th Street in Lower Manhattan and was submerged in the grit and chaos of an endlessly transforming city, while on the opposite side of the nation, the city of Los Angeles was embroiled in the LA riots that responded to the police brutality of the Rodney King beating. Wool’s nihilistic approach to painting is inextricably linked to the circumstances of its creation, and its potent visual force remains as powerful today as when it was painted more than two decades ago.

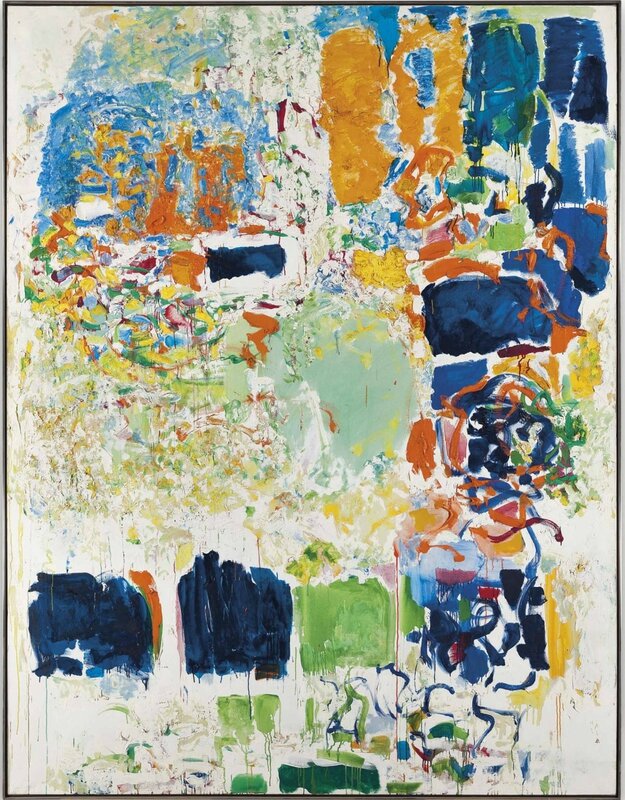

Lot 18. Joan Mitchell (1925-1992), Noon, signed 'Joan Mitchell' (lower left); signed again and titled '"Noon" Joan Mitchell' (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 103 x 79 in. (261.6 x 200.6 cm). Painted in 1969. Estimate $5,000,000 - $7,000,000. Price Realized $9,797,000 . Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Provenance: Galerie Jean Fournier et Cie, Paris and Martha Jackson Gallery, New York

Private collection, New Haven, 1973

Xavier Fourcade, Inc., New York

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1980

Literature: Joan Mitchell, exh. cat., Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, 1997, pp. 105 and 111 (installation view illustrated).

Exhibited: Paris, Galerie Jean Fournier et Cie, Joan Mitchell, May-June 1969.

Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Fondation Maeght, L'Art Vivant aux États-Unis, July-September 1970, p. 62.

Syracuse, Everson Museum of Art and New York, Martha Jackson Gallery, Joan Mitchell: My Five Years in the Country; An Exhibition of Forty-Nine Paintings, April-June 1972, p. 18 (illustrated).

Notes: A powerful painting rendered on a monumental scale, Joan Mitchell’s Noon captures the ephemeral quality of nature itself. This painting is a magnificent tour-de-force, a shimmering array of dazzling pigment that envelops the viewer in its vast, kaleidoscopic display. It evokes the pastoral splendor of the artist’s beloved Vétheuil, with its lush gardens and panoramic views of the Seine. In Noon, Mitchell liberally covers the canvas with a rich variety of brushwork, with a swiftness and ease that belies the underlying complexity of the painting’s internal structure. Thickly-brushed rectangles of orange, blue and green hover like dense clouds, while nearby, fine daubs of stippled paint linger like a slowly-lifting fog. Elsewhere, delicately-dappled strokes evoke the watery atmosphere of Monet’s water lilies. It embodies the newfound confidence that pervades Mitchell’s work of this era, as the effects of living in the French countryside breathed new life into her paintings.

Mitchell’s connection to the natural world has long dominated her work, but her permanent move to Vétheuil in 1968 allowed for a deeper, more powerful interaction. A year earlier, she had received a substantial inheritance after her mother’s passing, which she used to acquire a sprawling estate overlooking the Seine. The property featured a centuries-old stone house called La Tour, which became Mitchell’s home and studio, as well as the original house where Claude Monet lived and worked between 1878 and 1881. As Mitchell’s biographer Patricia Albers wrote: “Nearly every window at La Tour commanded a dazzling view: between river and the road below lay a wonderfully unmanicured wet-grass field dotted with locusts, pines, pear trees, willows, ginkgoes, and sycamores. … Birds twittered and swooped. Wind ruffled the foliage. … From the time she acquired Vétheuil, its colors and lights pervaded her work” (P. Albers, Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter, New York, 2011, p. 313).

Inspired by the bucolic splendor of the French countryside, Mitchell threw herself into life at La Tour, planting an abundant garden and renovating a studio space that accommodated much larger canvases than her earlier one on the rue Frémicourt in Paris. As was her habit, Mitchell woke around noon and worked into the late hours of the night, listening to Bach or Charlie Parker. At La Tour, the gauntlet of the great Impressionist masters had been passed, and Mitchell accepted the challenge with gusto. The paintings that followed, abound with wild, sumptuous color in floating slabs and planes arranged with nearly architectural precision.

Executed on increasingly larger and more expansive scales, these paintings reveal a mature artist at the pinnacle of her career. In 1972, the Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, organized the first major solo exhibition of Mitchell’s work, where Noon was exhibited alongside major paintings from her oeuvre. Its organizer, James Harithas, described Mitchell as “a terrific painter and, beyond that, an artist of profound and enduring insight” (J. Harithas, “Weather Paint,” Art News, May 1972, vol. 71, no. 3, p. 40). Two years later, a major retrospective of Mitchell’s work followed at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974.

Newer, emboldened color combinations flourished during this era. Here, Mitchell’s brilliant pairing of bold tangerine alongside fields of navy blue enlivens the canvas. Her orange is lively and buoyant; it zigs and zags its way around the surface much like sunlight dancing upon the slow-moving waters of the Seine. Her biographer recalled: “Something Joan had seen, perhaps a flower, made her fall in love with tangerine orange, a color she had long disliked. She decided to pair it with the lavender-tinged blue of the Gauloises cigarette pack” (P. Albers, Ibid., 2011, p. 322). Indeed, for Mitchell, color was deeply-felt, imbued with personal memories. In Noon, Mitchell’s shimmery yellow-orange is reminiscent of her earlier Sunflower of 1969, which in turn were influenced by van Gogh, an artist Mitchell had admired since her days at the Art Institute of Chicago. A recent publication described this effect: “orange appears, this sort of changeable mix of yellow and red, in which joy and torment, euphoria and sadness merge, in which we immediately note the memory of Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard and the French pastoral culture, of Gustav Klimt. … [It is] a melancholic golden light which dazzles” (S. Parmiggiani, “Joan Mitchell: In Search of a Lost Feeling,” in Nils Ohlsen,Joan Mitchell, exh. cat., Kunsthalle Emden, Reggio Emilia, Palazzo Magnani and Giverny, Musée des Impressionnismes, December 2008 - October 2009, p. 55).

Highly-disciplined and sharp-tongued, with a love of poetry and the outdoors, Mitchell rigorously confronted each canvas with increasing confidence and bravado, creating evanescent paintings that brim with luminous color. In Noon, Mitchell’s careful balance of rectangular planes takes a cue from Hans Hofmann, whose colorful architectural slabs similarly reflected the natural world, while the minute daubs of brushwork within the upper left area evoke the shimmering planes of Cézanne. These delicately-balanced compositions seem lit from within by an unknown light source, prompting one curator to describe them as “wet with light” (J. Harithas, ibid., p. 63).

Undeniably, the titles that Mitchell selected during this era were highly significant. In the present work, the word “noon” might refer to Mitchell’s waking hour, since she typically worked long into the night and awoke around mid-day. “Noon” might even perhaps correspond to Mitchell’s own metaphorical awakening and the renewal that took place in her work upon settling into Vétheuil.

In Noon, Mitchell effectively translates the very spirit of Vétheuil onto her canvas, essentially immortalizing a moment in time as if preserved in amber. Indeed, the splendor of Joan Mitchell’s beloved Vétheuil pervades every square inch of this masterpiece, a brilliant encapsulation of its heady scents and its sumptuous, resplendent landscape. Countless critics have chased this unnameable ephemeral quality in Mitchell’s work, but it is perhaps the artist herself who put it best: “Painting is a means of feeling living. Painting is the only art form except still photography which is without time. Music takes time to listen to and ends, writing takes time and ends, movies end, ideas and even sculpture take time. Painting does not. It never ends, it is the only thing that is both continuous and still. Then I can be very happy. It’s a still place” (J. Mitchell, quoted in Yves Michaud, “Conversations with Joan Mitchell, January 12, 1986,” in Joan Mitchell: New Paintings, exh. cat., Xavier Fourcade, New York, 1986, n.p.).

Lot 38. Richard Prince (B. 1949), Runaway Nurse, signed, titled and dated 'R. Prince Runaway Nurse 2005-06' (on the overlap), inkjet and acrylic on canvas, 110 ¼ x 66 in. (280 x 167.6 cm). Painted in 2005-2006. Estimate $5,000,000 - $7,000,000. Price Realized $9,797,000. World auction record. Photo: Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Provenance: Acquired directly from the artist by the present owner.

Exhibited: Wilmington, Delaware Art Museum, Exposed! Revealing Sources in Contemporary Art, August-October 2009.

Notes: “Your man hasn’t broken away from the past—and never will.” Nurse Gail Winters tried to forget her mother’s words. She and Dr. Craig Hadley were in love and that was all that mattered. But was it? Craig was divorced. He had nothing but hatred for his former celebrity wife, Vera Vaughn. But there was a matter of a million dollars involved and Vera was a very greedy woman. All Gail could offer Craig was her love. But was that enough when his ex-wife was offering him his child? It was a game with high stakes—and the winner would take all”—Text from Runaway Nurse by Florence Stuart, Macfadden/Bartell, New York, 1964.

Painted in 2006, Richard Prince’s Runaway Nurse is a steamy, lurid work, a flagrantly erotic example of the Nursepaintings that remain the iconic series in the artist’s oeuvre. Set ablaze in fiery crimson tones, the painting depicts a beautiful young nurse, whose bare shoulders and black lingerie make Runaway Nurse one of the most overtly sexual in the series. Prince lavishes attention on his heroine, from the highlights of her tender, glowing skin, to the delicate drape of her exposed blouse and the drips of aqueous black paint that seep from her lingerie. The painting’s title—“RUNAWAY NURSE”—appears above her, hovering in the air like a neon sign for some shady roadside bar. Suspenseful and seductive, the painting evokes the crime-laded intrigue of the original dime-store novel that inspired it—the 1948 Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye by American writer Horace McCoy. Dramatically enlarged to heroic scale, the heroine in Runaway Nurse becomes life-sized, surrounded by the molten aura that Prince creates, accentuating the pent-up desire and salacious content of the original novel, to create an image that’s even more provocative than the character in the original book.

Runaway Nurse is a heady painting, its imagery overtly sexual and its palette set ablaze in roaring tones of fiery crimson. Prince’s scantily-clad nurse is lovingly detailed, from the delicate daubs of paint that describe the tender features of her face to the expertly-modeled drape of her opened blouse. The luminous quality of her skin gives off a radiant glow when set against the painting’s brushy background. Standing at the foot of a bass bed, she displays herself for the viewer, her blouse opened to reveal bare shoulders and black lingerie, yet she demurs by turning her head to the side and closing her eyes in silent dissent. A delicate wash of translucent white acrylic indicates the nurse’s mask that covers her nose and mouth, yet her parted red lips are still visible beneath. Since their inception in 2003, Prince’s Nursepaintings have long possessed a certain hushed eroticism, yet Runaway Nurse is one of the few examples to depict an overtly semi-nude figure. Along with the nurse’s hat that rests upon the back of her head, the mask is the only remaining vestige of her identity, as the viewer puzzles over the mystery that surrounds her dramatic circumstances.

A widely-known bibliophile whose collection contains more than 3,000 titles, Richard Prince is drawn to the trumped up melodrama of vintage dime-store novels, and regularly trawls his collection for inspiration. In Runaway Nurse,Prince conflates the imagery of not one, but two, separate book covers. The first is Runaway Nurse by the novelist Florence Stuart. Written in 1964, the book’s cover depicts a young nurse wearing her signature white uniform. Rendered in profile, she appears rather distraught, with downcast eyes and a subtle pout, as if caught in a moment of thoughtful turmoil. The précis of the original book, which sold for 40-cents when it was published in 1964, describes the hyperbolic drama of its contents: “Was young Nurse Winters enough of a woman to make the man she loved forget his past?” which is still discernible beneath a layer of brushy crimson above the painting’s title. On the original cover, the young Nurse Winters must vie for affection from her fiancé (a doctor) who is visible in the background along with his celebrity ex-wife, who in the novel conspires to win him back in hopes of securing a million-dollar inheritance.

The steamy imagery from a second novel, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, by the film noir novelist Horace McCoy, is the second book that Prince appropriates in Runaway Nurse. This book features an original illustration by the artist James Avati that depicts a scantily-clad seductress whose open blouse revealed a titillating amount of flesh considering the book’s original publication date of 1948. A work of quintessential film noir, its cover reads: “Love as hot as a blow torch...crime as vicious as the jungle.” And its cover illustration alludes to the hardboiled story of the novel’s principal characters, Ralph Cotter, a career criminal who’s recently escaped from prison and Margaret Dobson, a wealthy heiress who sets her sights on Cotter and becomes embroiled in a steamy affair.

The book’s graphic violence and vividly sexual scenes are surprising for the era in which they were written, and Avati’s illustration conveys a key scene in the book, in which Margaret and Ralph are caught in flagrante delicto. In the illustration, Margaret’s posture is emblematic of her role as a stereotypical femme fatale—she reveals her semi-nude body to the viewer yet her back is turned to Cotter and her eyes remain closed. Seen in this light, she seems to offer something that is off-limits to her male paramour, or at least available, but for a price. Seated upon the bed, Cotter grabs the railing and looks on with skepticism, a sneer slightly visible upon his cigarette-smoking mouth, the bars of the brass bed further separating him from Margaret, reminding him of his time spent behind bars. In 1950, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye was made into a film of the same name starring James Cagney, and was banned in Ohio for its salacious imagery.

It is telling that Prince would conflate two vintage novels in Runaway Nurse—one of them a lost classic of film noir and another quite its opposite, the sub-genre of “nurse romance”—since the stereotypical construction of gender and its corresponding sexual politics have long influenced his work. Coming of age in the 1980s alongside artists like Cindy Sherman and Sherrie Levine, who became known as the Pictures Generation, Prince explored sexual identity through the construction of gender in magazine ads and photographs. His early photographs of fashion models were appropriated from the ads he culled through while working for Time/Life, and by isolating the image out of context, Prince was able to call attention to their construction of the feminine ideal as an inherent falsehood. In the series that followed, from Cowboys to Girlfriends, Prince continued to interrogate the way in which gender and sexuality is framed by the media. He continues to do so in Runaway Nurse, conflating the loose-talking, amoral femme fatale of McCoy’s crime novel with the hapless, love-struck nurse in Florence Stuart’s Runaway Nurse. The character he portrays is caught at a crossroads between two extremes: the virgin or the whore. Her choice isn’t readily apparent, allowing the painting to delve into the controversial nature of female sexuality, as implied in its hidden source material.

Further source imagery for Runaway Nurse might find precedent in the infamous painting by John Singer SargentPortrait of Madame X, which caused scandal and outrage when it was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1884. The flagrantly bare décolletage, cinched waist and pale skin of Sargent’s model created outcry when the painting was exhibited, and revealed the identity of Madame X as an American expatriate named Virginie Gautreau. Gautreau had a notorious reputation for infidelity that was rumored through the elite Parisian circles that would have viewed the 1884 Salon. In Runaway Nurse, Prince seems to mimic the creamy skin of Madame X’s bare shoulders and the aloof posture of her stance, especially the way she both presents herself toward the viewer yet looks away, her face rendered in profile. In Runaway Nurse, the female figure displays herself in front of a brass bed, her delicate hands and wrists coming to rest upon its cold, metal frame. This, in combination with the painting’s lurid red background and the torn-open appearance of her blouse, appear to present the figure in sadomasochistic terms; one can imagine her wrists tied to the bed frame, her clothing torn open by a lover’s strong hands. The brass bed might also remind the viewer of the inherent parameters of the painting’s frame and the visual barrier that exists between the canvas and the viewer’s gaze.

Throughout his work, Richard Prince delves into the forgotten and outmoded narratives that have framed the way we perceive ourselves, from pulp fiction to fashion magazines, to explore and provoke the stereotypes that pervade concepts of sexuality, desire and control. His obsession with subculture reveals a truer understanding of ourselves, though not obvious or flattering at times. He has said, “I’ve never wanted to be transgressive or to make an image that was unacceptable or that I would have to censor,” he said. “But that being said, I think a lot of the imagery I do create is sexual, and I hope it does turn people on” (R. Prince, quoted in R. Kennedy, “Two Artists United By Devotion to Women,” New York Times, 23 December 2008, sec. C, p. 1). In spite of the predictability of the heroines Prince depicts, they are quite complex figures that both exaggerate and undermine the stereotypes they imply, making them closer to real-life women than the one-sided caricatures they seem.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F81%2F89%2F119589%2F129069023_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F95%2F36%2F119589%2F127146553_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F11%2F119589%2F125968385_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F69%2F75%2F119589%2F125961208_o.jpg)