Centennial exhibition celebrates landmark acquisition of Benkaim collection of imperial Mughal paintings

Posthumous portrait of the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah (r. 1719–48) holding a falcon, 1764. Muhammad Rizavi Hindi (Indian, active mid-1700s). Mughal India, probably Lucknow. Opaque watercolor with gold on paper; 28 x 23.8 cm (page); 14.4 x 10.3 cm (painting). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift in honor of Madeline Neves Clapp; Gift of Mrs. Henry White Cannon by exchange; Bequest of Louise T. Cooper; Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund; From the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection, 2013.347 (recto).

CLEVELAND, OH.- Art and Stories from Mughal India presents the story of the Mughals— and stories for the Mughals—in 100 exquisite paintings from the 1500s to 1800s. The exhibition and accompanying Mughal painting collection catalogue celebrate the Cleveland Museum of Art’s centennial with works drawn from the 2013 landmark acquisition of the Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Ralph Benkaim Collection of Deccan and Mughal paintings, many exhibited and published for the first time. Complementing the paintings are 39 objects including costume, textiles, jewelry, arms and armor, architectural elements and decorative arts, some on loan from other prominent institutions, such as the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, the Brooklyn Museum and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University. These objects resonate with details in the paintings and bring the sumptuous material culture of the Mughal world to life. Art and Stories from Mughal India is on view in the Kelvin and Eleanor Smith Foundation Hall from July 31, 2016 through October 23, 2016, and is free to the public in celebration of the museum’s centennial year.

Layla and Majnun in the wilderness with animals, from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi (Indian, 1253–1325), about 1590–1600. Attributed to Sanwalah (Indian, active about 1580–1600). Mughal India, made for Akbar (reigned 1556–1605). Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper; 24.9 x 16.8 cm (page); 18.6 x 16.2 cm (painting). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift in honor of Madeline Neves Clapp; Gift of Mrs. Henry White Cannon by exchange; Bequest of Louise T. Cooper; Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund; From the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection, 2013.301 (recto).

“The Cleveland Museum of Art has long boasted a particularly fine holding of Indian art, and with the acquisition of the Benkaim collection of Mughal paintings, we are now fortunate to have an extraordinary representation of one of its most celebrated artistic traditions,” said William M. Griswold, Director. “This exhibition—beautifully curated and magnificently installed—vividly evokes the richness and cosmopolitanism of one of the world’s great empires.”

The Annunciation, from a Mir’at al-quds (Mirror of Holiness) of Father Jerome Xavier (Spanish, 1549–1617), 1602–4. Mughal India, Allahabad, made for Prince Salim (1569–1627). Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper; 26.2 x 15.4 cm (page); 20.6 x 10.2 cm (painting). The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund, 2005.145.2.

The Mughal Empire existed for more than 300 years, from 1526 until the advent of British colonial rule in 1858. It encompassed territory that included vast portions of the Indian subcontinent and Afghanistan. The Mughal rulers were Central Asian Muslims who assimilated many religious faiths under their administration. Famed for its distinctive architecture, including the Taj Mahal, the Mughal Empire is also renowned for its colorful and engaging paintings, many taking the form of scenes from narrative tales.

Nur Jahan holding a portrait of Emperor Jahangir, about 1627; borders added 1800s. Mughal India. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; 30 x 22.1 cm (page); 13.6 x 6.4 cm (painting). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift in honor of Madeline Neves Clapp; Gift of Mrs. Henry White Cannon by exchange; Bequest of Louise T. Cooper;Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund; From the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection, 2013.325 (recto).

Art and Stories from Mughal India is organized into eight sections based on the Persian idea of the nama. Nama may be translated as any of a number of English words, among them: book, tale, adventure, story, account, life and memoir. Paintings were integral to the production of namas in book form for royal collections in Mughal India. Art and Stories from Mughal India sets the paintings, now long separated from their bound volumes, into their nama contexts. Four of the exhibition’s sections focus on a specific nama: a fable, a sacred biography, an epic, and a mystic romance. Many of the paintings, long celebrated for their vivid color, startling detail and alluring sense of realism, are displayed double-sided to show complete folios from albums and manuscripts, a constant reminder of their original status as part of a larger book or series.

Women enjoying the river at the forest’s edge, about 1765. Mughal India, Murshidabad or Lucknow. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; 33.1 x 24.9 cm (page); 30.5 x 22.2 cm (painting). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift in honor of Madeline Neves Clapp; Gift of Mrs. Henry White Cannon by exchange; Bequest of Louise T. Cooper; Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund; From the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection, 2013.351 (recto).

“The paintings are products of a powerful, multiethnic dynasty of rulers who valued art and literature as essential elements of court life,” said Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, the George P. Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art. “They were made to inspire awe and delight, and this exhibition aims to do the same by making them accessible to audiences today.”

Sumptuously designed to evoke the spaces of Mughal palace interiors and verandas where paintings were kept and viewed, the exhibition opens with a 25-foot-long 16th-century floral arabesque carpet, rarely seen because of its scale. The first two galleries are devoted to Mughal paintings made for Akbar, the third Mughal emperor (r. 1556–1605), who saw to it that his copies of fables, adventures and histories were accompanied by ample numbers of paintings. On view are some of the earliest works from Akbar’s reign by celebrated artists, such as Basavana (Basawan) and Dasavanta (Daswanth), from the Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot), and the culminating scene from the Hamza-nama (Adventures of Hamza), 70 cm in height, one of the few surviving pages from this massive 1,400-folio project in which the Mughal style became thoroughly synthesized.

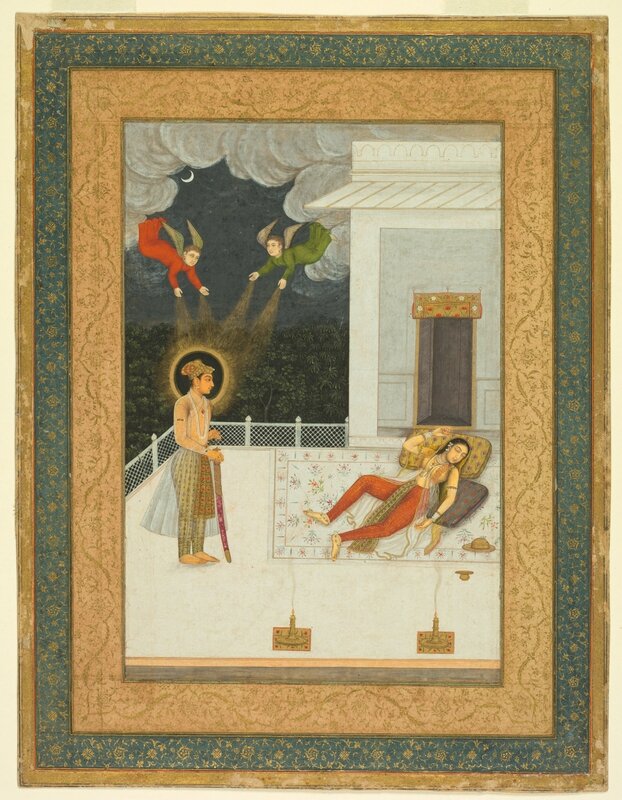

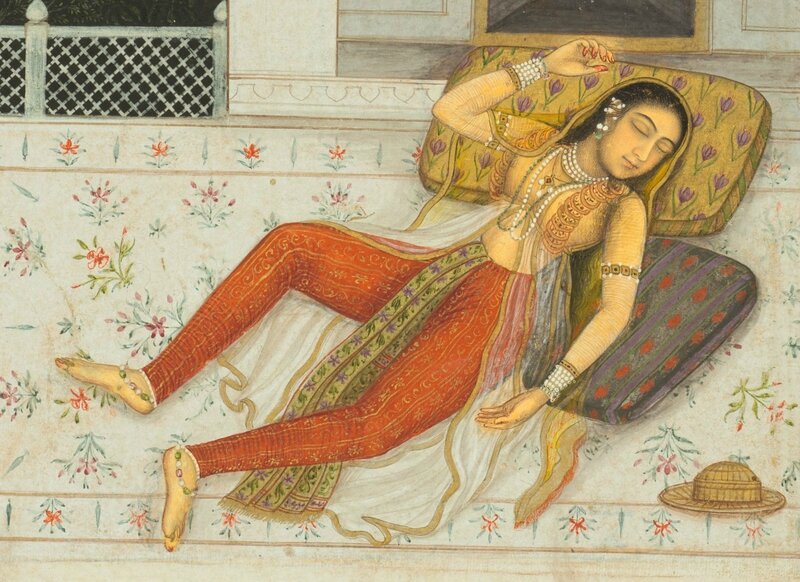

The dream of Zulaykha, from the Amber Album, about 1670. Mughal India. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; 32 x 24.4 cm (page); 21.9 x 15.4 cm (painting). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift in honor of Madeline Neves Clapp; Gift of Mrs. Henry White Cannon by exchange; Bequest of Louise T. Cooper; Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund; From the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection, 2013.332 (recto).

The next two galleries explore the relationship between Akbar and his oldest son, Salim, whose birth in 1569 was cause for great celebration. By 1600, Salim was ready to lead the empire and mutinously set up his own court where he brought paintings, artists and manuscripts from Akbar’s palace and commissioned new works, such as the illustrated Mir’at al-quds (Mirror of Holiness), a biography of Jesus written in Persian by a Spanish Jesuit priest at the Mughal court, completed in 1602. Like the Tutinama (Tales of a Parrot), the Mir’at al-quds manuscript is remarkable not only for its historical importance and artistic beauty, but because it survives nearly intact, though unbound, with few missing pages. Both manuscripts, crucial for the study of Mughal painting, are kept in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and most of their folios have never before been shown.

Katar dagger, 1700s. India. Iron handle with gold inlay steel blade; wooden sheath with velvet cover, brass boss, iron tip with gold inlay; 45.6 x 8.2 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Morris and Eleanor Everett, 1985.119.

The story of the Mughals continues with works made for and collected by Emperor Jahangir—the name Prince Salim took after the death of Akbar in 1605—as well as his son Shah Jahan (r. 1627–58) and grandson Alamgir (r. 1658–1707). This period spanning the 17th century saw the production of some of the most exquisite paintings and objects ever made for the Mughals. Textiles, courtly arms, garments, jades, marble architectural elements and porcelains bring to life the painted depictions of the Mughal court’s refined splendor at the height of its wealth.

Hookah bowl, about 1700. Mughal India. Gold on blue glass; h. 19.8 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cornelia Blakemore Warner Fund, 1961.44.

Concluding the exhibition is a large, dramatic gallery, painted black in keeping with depictions of the interiors of 18th-century Mughal palaces, with paintings framed in gold, hookah bowls, jewels, a vina, lush textiles and a shimmering millefleurs carpet. The assemblage celebrates the joy in Mughal art of the mid-1700s. The scenes predominantly take place in the world of women and the harem, where the emperor Muhammad Shah (r. 1719–48), who was largely responsible for the reinvigoration of imperial Mughal painting, grew up, sheltered by his powerful mother from the murderous intrigues that wracked the court after the death of Alamgir in 1707.

Ring, 1700s–1800s. India. Gold, enamel, and chased stones; diam. 2.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Edward L. Whittemore Fund, 1944.68.

Throughout the exhibition viewers will note the international character of Mughal art and culture. Flourishing during the Age of Expansion between the 1500s and 1700s, Mughal India was the source for goods and natural resources coveted throughout the Western world, and visitors to the exhibition will encounter the origins of familiar aspects of current daily life in the works of art on view.

Wine cup in the shape of a turban gourd, 1625–50. Mughal India. Nephrite. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, The Avery Brundage Collection, B60J485. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Architectural panel, 1700s or early 1800s. Mughal India. Marble inlaid with variegated semiprecious stones; 46.4 x 24.4 x 7.5 cm. The Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Gary Smith, 86.189.4.

Pierced railing, about 1655. Mughal India. Marble; 33.5 x 64 x 5.5 cm. Harvard Art Museums / Arthur M. Sackler Museum, The Stuart Cary Welch Collection, Gift of Edith I. Welch in memory of Stuart Cary Welch, 2009.202.67. Image © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F52%2F119589%2F113161133_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F64%2F119589%2F112025319_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F82%2F16%2F119589%2F96474434_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_c453b7_439605604-1657274835042529-47869416345.jpg)