17th-century Chinese paintings from the Tsao Family Collection on view at LACMA

Bada Shanren, Rock and Bird, from the album Landscape, Flowers, Birds, and Calligraphy, Qing dynasty, Kangxi reign, 1698, Album leaf; ink on paper, 30x21.9cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

LOS ANGELES, CA.- The Los Angeles County Museum of Art presents Alternative Dreams: 17th-Century Chinese Paintings from the Tsao Family Collection, one of the finest existing collections of Chinese paintings in the United States, formed over a period of 50 years by the late San Francisco Bay Area collector and dealer Jung Ying Tsao (1923–2011).

The 17th century witnessed the fall of the Chinese-ruled Ming dynasty (1368– 1644), the founding of the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty (1644–1911), and was one of the most turbulent and creative eras in the history of Chinese art. Comprising over 120 paintings, the exhibition explores ways in which artists of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties used painting, calligraphy, and poetry to create new identities as a means of negotiating the social disruptions that accompanied the fall of the Ming dynasty. Alternative Dreams presents work by over 80 artists, many of whom are the most famous painters of this period—including scholars, officials, and Buddhist monks.

Zhang Xuezeng, Landscape Inspired by a Poem by Wen Tingyun (812–870), from the album,Landscapes with Towers, Qing dynasty, ca. 1640–50, Album leaf; ink on paper, 28 × 18.4 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

“Alternative Dreams is a window into a lost world. The window comprises Chinese paintings and their accompanying calligraphies, through which one can explore key aspects of Chinese culture,” says Stephen Little, Florence & Harry Sloan Curator of Chinese Art at LACMA. “Among these is the respect for antiquity and the importance—for an artist—of transforming the past into something new and relevant for the present.”

Alternative Dreams is divided into nine sections arranged both chronologically and geographically: Dong Qichang and Painting in Songjiang; the Nine Friends of Painting; Painting in Suzhou and Hangzhou; Painting in Fujian and Jiangxi; Painting in Nanjing; The Anhui School; The Orthodox School; Buddhist Monks; and Flower and Bird Painting.

Hongren, Landscape with Pagoda, from the album, Landscapes and Calligraphies, Qing dynasty, ca. 1651–64, Album leaf; ink and color on paper, 18.7 × 12.9 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

The first section of the exhibition, Dong Qichang and Painting in Songjiang, is devoted to Dong Qichang (1555–1636)—one of the most important painters and calligraphers of the Ming dynasty—and several of his followers. Dong was pivotal in the development of late Ming and early Qing painting. His paintings and theories on art history had a major impact throughout the rest of the 17th century and later, even into the modern era. Dong Qichang was both a remarkably innovative artist and an important art historian and theoretician who created the Southern School lineage of literati painting. By the 17th century the literati style of painting had become the dominant mode of painting. In addition, several of the calligraphic works in the Tsao Family Collection shed light on Dong’s spiritual beliefs and practices, aspects of his life rarely discussed in depth. Dong’s works include examples of painting and calligraphy and, in several cases, works that combine both.

Ding Yunpeng, Luohan and Attendant,Ming dynasty, late 16th–early 17th century Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper 35.6 × 32.4 cm (14 × 12 3⁄4 in.) The Tsao Family Collection.

The Nine Friends of Painting is based on the Qing dynasty poet and painter Wu Weiye’s poem, Song of the Nine Friends of Painting. While the painters never actually formed a coherent group, the Nine Friends have endured as a fixture in the history of Chinese painting. This is no doubt because in his poem Wu Weiye conveys startlingly vivid images of the artists’ paintings, and his reactions are visceral. The Nine Friends included Dong Qichang, Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Li Liufang, Yang Wencong, Zhang Xuezeng, Cheng Jiasui, Bian Wenyu, and Shao Mi. Also included in this section are several painters loosely related to the Nine Friends: Wu Weiye himself, Puhe, Yan Shengsun, and Zou Xianji.

Gong Xian, Thatched Hall among Dense Trees (detail), Hanging scroll; ink on paper, 186.1 × 49.8 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

Painting in Suzhou and Hangzhou examines the work that came from two of the most affluent and culturally significant cities in the history of Chinese art. In the 16th century, Suzhou witnessed the flourishing of the Wu School of painting. Led by its towering giants Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming, the Wu School was characterized by delicate brushwork and understated coloring—a contrast to the bolder and more calligraphic new landscape styles of Dong Qichang and his followers. Hangzhou had been the capital of the Southern Song dynasty in the 12th and 13th centuries and the birthplace of the Ming dynasty Zhe School of court and professional painting.

Gong Xian, Landscape (detail), Qing dynasty, Kangxi reign, 1674, Set of 4 hanging scrolls; ink on silk, 280 × 58.1 cm, each scroll, The Tsao Family Collection.

Painting in Fujian and Jiangxi explores the importance of these two southern provinces as major cultural and economic centers in the centuries leading up to the late Ming dynasty. Several of the most innovative painters from this period were natives of Fujian, including Wu Bin, Huang Daozhou, Wang Jianzhang, and Zhang Ruitu. Fujian is also identified with several key ceramic types, including Song dynasty (960–1279) Jian ware tea bowls and the late Ming porcelain type known as Dehua. In the 17th century, Fujian, with its major ports of Quanzhou and Fuzhou, played an important role in international sea trade. Jiangxi Province was also a major cultural and commercial center and home to many famous Chinese artists and intellectuals. Known for the great kiln center of Jingdezhen, which produced most of China’s blueand-white porcelains from the 14th century onward, Jiangxi played a key role in the Ming economy. Jiangxi’s capital city, Nanchang, was a major administrative center in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, attracting many talented artists and producing several important 17th-century painters, represented in this section by Luo Mu and Bada Shanren (Zhu Da).

Shen Hao, Landscape in the style of Ni Zan (1301–1374), from the album, Landscapes, Qing dynasty, Shunzhi reign, 1652, Album leaf; ink on paper, 29.8 × 24.1 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

Painting in Nanjing considers the notable painters and artistic styles that emerged from this vital political, commercial, and artistic center during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Nanjing had symbolic relevance in the 17th-century because it had been the first capital of the Ming dynasty, prior to the move of the capital to Beijing in the early 15th century. Nanjing continued to function as the secondary capital of the Ming, complete with its own imperial palace. In the troubled early years of the Qing dynasty, Nanjing figured prominently as a site linked to the fallen dynasty, and was a haven for many Ming loyalists. In 17th-century painting, calligraphy, and literature, Nanjing resonated as a nexus of nostalgia and lost dreams. The city was a major spiritual center and became home to Buddhist temples and monasteries. Many of the most important 17th-century Chinese painters either came from or lived in Nanjing, and the city gave birth to the eponymous Nanjing School—not an organized school of painting as such, but instead a group of artists whose works share certain eclectic features. These include celebrations of the visual beauty of Nanjing and its environs, a penchant for meticulously detailed views of nature with sophisticated atmospheric effects, and dramatic uses of light and dark ink.

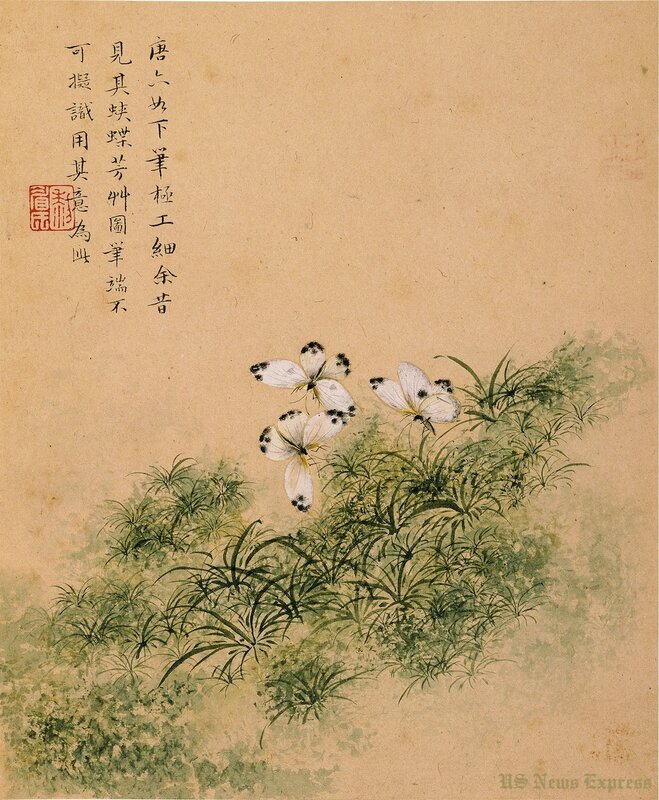

Zou Xianji, Butterflies among Fragrant Grasses, in the Style of Tang Yin (1470–1523), from the album, Flowers, Qing dynasty, Kangxi reign, 1668, Album leaf; ink and color on paper, 27.3 × 22.2 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

In the 17th century, a distinct style of landscape painting, characterized by dry brushwork and the simplification of landscape forms, developed in Anhui Province. The Anhui School style evolved from several sources, including the Wu School, the late Ming achievements of Dong Qichang (both theoretical and technical), and the unique, otherworldly topography of the Yellow Mountains (Huangshan), located in southern Anhui. This section includes several painters who, despite not being from Anhui, are often grouped with the Anhui painters because of similarities in style and technique. Along with the dry brushwork and simplification of forms came a love of spatial ambiguities, which are often visible in works by painters Hongren and Dai Benxiao and in the works of artists from other parts of China who were heavily influenced by the Anhui style, including Zou Zhilin and Fu Shan. Anhui merchants were engaged in many lucrative businesses in the 17th century, including the manufacture of the finest papers, brushes, inks and inkstones, woodblock printing, and the transport of porcelain from the great kiln center of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province to other parts of China.

Kuncan, Landscape (detail), Qing dynasty, Kangxi reign, 1671, Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper, 133.4 × 30.5 cm (52 1⁄2 × 12 in.), The Tsao Family Collection.

The Orthodox School takes its name from the term “orthodox lineage” (zheng zong). Painters of this school believed that they were the sole carriers of the flame of Dong Qichang’s Southern School of painting. The most famous of the Orthodox School painters were known as the Four Wangs, a group of early Qing dynasty landscape painters. Three of the Four Wangs were born into privileged households— Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, and Wang Yuanqi. Like Wang Shimin and Wang Jian, Wang Yuanqi was born into affluence and served as a high-ranking official in the Manchu government. He was also one of the Kangxi emperor’s favorite painters. Painters of the Orthodox School played an important role in landscape painting at the imperial court, especially as it represented continuity with a distant and glorious past. This section is represented with works by the Orthodox School painters Wang Hui and Yun Shouping.

Fu Shan, Horsemouth Cliff, from the album, Landscapes, Qing dynasty, ca. 1659, Album leaf; ink on paper, 28.6 × 32.1 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

Buddhist Monks considers the thematic overlap that many important painters had with Buddhist philosophies and traditions. The artists Hongren, Kuncan, Bada Shanren, and Shitao all became Buddhist monks, either before or after the Manchu conquest of 1644. They never, however, formed an actual group or school, and their painting styles are noticeably different. They were active in different geographical areas: Hongren in Anhui Province; Kuncan in Nanjing; Bada Shanren in Jiangxi Province; and Shitao in Yangzhou, Beijing, Anhui, and Nanjing. All four artists were born during the Ming dynasty and died in the early Qing Kangxi reign. Although it is often assumed that these artists became Buddhist monks as a political act, closer examination of their lives reveals that they were serious Buddhist practitioners. As such they were knowledgeable about Buddhist history, philosophy, and metaphysics. Each was, at one time or another, a Buddhist ritual master. Many more 17th-century artists either studied Buddhism or found refuge in the Buddhist faith than is generally realized. Even though they were not ordained as Buddhist monks, these lay Buddhists included Dong Qichang, Li Liufang, Ding Yunpeng, Gao Cen, Zhang Feng, Ma Shouzhen, and Shao Mi.

Dong Qichang, Winter Landscape in the style of Li Cheng & Calligraphy (detail), Ming dynasty, Wanli reign, 1613, Handscroll; ink on silk 26.4 × 257.8 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

The final section, Flower and Bird Painting, highlights the important role these auspicious symbols serve in Chinese culture. Certain groups of plants and birds are especially famous: the Three Friends of Winter (pine, plum blossoms, and bamboo), for example, represent strength, purity, and resilience. Similarly, birds function as potent symbols: cranes are emblematic of longevity and immortality, and magpies symbolize happiness and marriage.

Yang Bu, Farewell by a River in Spring (detail), Qing dynasty, Shunzhi reign, 1652, Handscroll; ink and color on paper, 25.5 × 278.5 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

Chen Jiru, Cloudy Mountains in the Style of Mi Fu, Ming dynasty, Wanli reign, 1596, Hanging scroll; ink on satin, 81.9 × 27.9 cm, The Tsao Family Collection.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F54%2F119589%2F110796097_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F61%2F119589%2F30155334_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_65a1d8_telechargement-31.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240331%2Fob_7209d9_117-1.jpg)