Exhibition explores the paintings, sculpture, furniture, ivories and silverworks of the Altiplano

Plaque from an Alter Frontal, 1700 - 1750. Artist/maker unknown, Bolivian Silver, repoussé, chased, engraved, and burnished, 10 1/2 x 21 1/8 x 1 1/4 inches (26.7 x 53.7 x 3.2 cm). Roberta Richard Huber Collection. Photo courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.

SAN ANTONIO, TX.- Highest Heaven, on view at the San Antonio Museum of Art, explores the paintings, sculpture, furniture, ivories and silverworks of the Altiplano, or high plains, of South America in the 18th century. Through the work of both well-regarded masters and lesser-known artists, Highest Heaven highlights the role of art in the establishment of new city centers in the Spanish Empire, and the propagation of the Christian faith among indigenous peoples. Drawn exclusively from the distinguished collection of Roberta and Richard Huber, the exhibition highlights the distinct visual language created by the cultural and creative exchanges that occurred between Spain and Portugal and their South American colonies. The exhibition will remain on view through September 4, 2016, before traveling to the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California in October, and to the Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts the following March.

Saint Michael the Archangel, Peruvian, Cuzco, 18th century. Oil on canvas, h. 79 1/8 in. (200 cm); w. 61 in. (154.9 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art

The exhibition features more than 100 works, including religious paintings, carved and gilded wooden sculptures, intimate ivories, and silverwork, originally housed in ecclesiastical and private collections throughout the former colonial possessions of Spain and Portugal. The majority of these works were created for functional purposes, as articles of faith or symbols of civic order, and were displayed in a manner that enhanced religious understanding, brought social order, and spurred conversion among colonial populations. Highest Heaven examines these uses, focusing in particular on the translation of Christian imagery to the colonies and the ways in which these works and objects worked to establish an ordered society and were integrated into religious life. The exhibition includes approximately 20 recent acquisitions by the Hubers, many of which have never before been seen in a museum exhibition.

Missal Stand, Peruvian or Bolivian, late 18th century. Silver, repoussé, chased, engraved and wood, h. 12 in. (30.5 cm); w. 14 15/16 in. (37.9 cm); d. 11 13/16 in. (30 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art

"A central component of our mission is to examine and communicate the historic and cultural contexts of artworks, along with the objects themselves. Highest Heaven is an exciting opportunity to not only investigate the aesthetic beauty of this art, but also the significant role that it played in the cultural, religious, and social lives of these peoples," said Katherine Luber, The Kelso Director of San Antonio Museum of Art. "We are grateful to Roberta and Richard for their collecting vision and the chance to share this incredible collection with our audiences. San Antonio is a city rich in history and diversity, and we look forward to engaging our community with this work, which we think will have a particular meaning here."

Our Lady of Candlemas with Donors, Bolivian, Potosí, 1799. Oil on canvas; h. 27 9/16 in. (70.0 cm); w. 20 in. (50.8 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art

The exhibition is co-curated by William Keyse Rudolph, Mellon Chief Curator and Marie and Hugh Halff Curator of American Art, and Marion J. Oettinger Jr, Curator of Latin American Art. Unlike many previous exhibitions of Colonial Art, which have arranged objects by media, Highest Heaven has been organized according to iconography. After an introductory section that explores a group of objects made for secular life, the exhibition considers the art works religiously, from the angels and archangels that foretold the coming of Jesus Christ, through imagery dealing with the life of Christ and spread of the gospel, to the importance of the Virgin Mary and the saints. Each section of the exhibition contains a mixture of works of art in all media, from paintings to sculpture to silverwork and ivories.

Christ on the Cross, Bolivian, 18th century, Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Altiplano stretches from northern Argentina to the flatlands of Peru, and much of the exhibition focuses on works produced by workshops in the major cities of Cuzco and Lima in modern day Peru and Potosi in modern day Bolivia, where both European and native artists practiced. Paintings and sculpture served primarily to disseminate Christian images and faith to the New World, while works in ivory and silver underscored the wealth and prosperity of the growing Empire. Paintings also frequently depicted major colonial cities to both capture their urban fabric and educate those back home on the appearance and existence of the colonies.

Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, Indo-Portuguese, 17th century, Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Bruce Schwarz.

With the extensive growth of trade across the Empire, works of art took on a range of styles that represented European traditions and local idioms. In some instances, European aesthetics and subjects were replicated directly. In others, European saints, idols, and figures took on the appearance of native populations, enhancing their relevance and influence. Yet, in other work, Christian symbols were incorporated into scenes of local rural and urban life. Together, these distinct yet interrelated approaches, created a new visual culture that represented the expansiveness of the Empire, and spoke to the integration of a diversity of peoples into a single faith.

Trunk Decorated with Spanish Colonial Paintings, South American, 18th century. Oil on canvas over wood, h. 20 in. (50.8 cm); w. 38 in. (96.5 cm); d. 21 in. (53.3 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

"In contrast to other areas of Spanish colonial scholarship, such as New Spain (present-day Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America), much less is known about the artists, workshop practices, and even the names of South American artists," said Luber. "Collectors are often the first to blaze the trail of discovery, and then the scholarship follows. A show like Highest Heaven opens up avenues of investigation. We are producing a catalogue that we hope will spur additional scholarship in the field. That's part of what is so exciting about this exhibition."

Our Lady of Mount Carmel with Bishop Saints, 1764. Gaspar Miguel de Barrio, Bolivia, Potosi 1706 - after 1706. Oil on canvas, Image 38 3/4 x 33 1/16 inches (98.5 x 84 cm). Framed 45 1/2 x 39 3/8 x 3 1/4 inches (115.6 x 100 x 8.3 cm). Promised gift of the Roberta Richard Huber Collection.

Highlights from the exhibition, include:

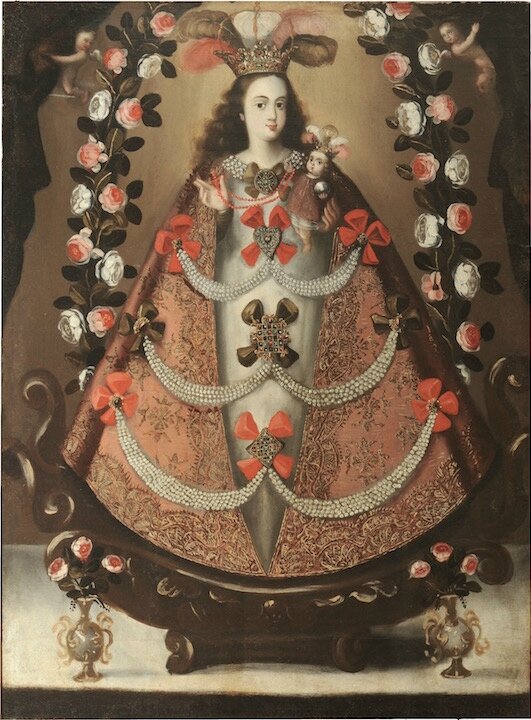

• Our Lady of the Rosary of Pomata, Bolivia, 17th Century, a moving example of the painted portrayals of the dressed virgin, which mimicked the practice of dressing statues of the Virgin for ceremonies and festivals. This painting style was unique to the Spanish Colonial world, and highlighted the incorporation of the Virgin into the experience of common life.

Our Lady of the Rosary of Pomata, Bolivian, late 17th or 18th century. Oil on canvas, h. 45 ¼ in. (114.9 cm); w. 39 3/8 in. (100 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art

• Christ Descending Into Hell, a large 18th Century Peruvian painting that dramatically shows a heroic Christ redeeming the souls of humanity—and one of the Hubers' recent acquisitions;

“Christ Descending into Hell”, Peruvian, 18th century, oil on canvas. Photo: Courtesy San Antonio Museum Of Art

• A portrait of the Countess of Monteblanco and Miranar, attributed to the 18th-Century Peruvian painter Cristobal Lozano. A splendid portrait of one of the wealthiest women in the Viceroyalty of Peru, the painting shows how the Colonial elite of the New World displayed their status through elaborate representations that enumerated their sophistication and power;

Attributed to Cristóbal Lozano (Peruvian, 1705-1776), Rosa de Salazar y Gabiño, Countess of Monteblanco and Montemar, 1764-1771. Oil on canvas, h. 37 13/16 in. (94.5 cm); w. 29 ¾ in. (75.6 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photo: Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

• Rest on the Flight Into Egypt, an 18th Century Bolivian painting that humanizes the Holy Family. It shows the Virgin Mary washing the Christ Child's diapers, while recognizably South American flora and fauna populate the background;

“Rest on the Flight into Egypt”, Bolivian, 18th century, Oil on canvas. Photo: Courtesy San Antonio Museum Of Art

• Christ Child as Salvator Mundi, an extraordinary Indo-Portuguese ivory sculpture that communicates the humanity and lovability of the Christ Child and depicts a vision of perfect peace and the promise of salvation. These intimate, small scale sculptures were carved by craftsmen in the Spanish and Portuguese possessions of Goa and the Philippines and exported throughout the Colonial World as objects for devotion, testifying to the global nature of the Colonial art world;

Christ Child as Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World), Indo-Portuguese, 17th century. Ivory with paint, gilding, polychromy; h. 25 in. (63.5 cm); w. 8 in. (20.3 cm); d. 7 ½ in. (19 cm). Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art

• An 18th Century Peruvian Pax, with a scene of Christ revealed to the people after his trial by Pontius Pilate. Made from the abundant silver deposits in the Viceroyalty of Peru, this devotional tablets were used in Mass as an object of veneration.

Pax Depicting the Ecce Homo, Peruvian, 18th century, Roberta and Richard Huber Collection. Photograph by Graydon Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F96%2F119589%2F129836760_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F33%2F99%2F119589%2F129627838_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F83%2F119589%2F129627729_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F37%2F119589%2F129627693_o.jpg)