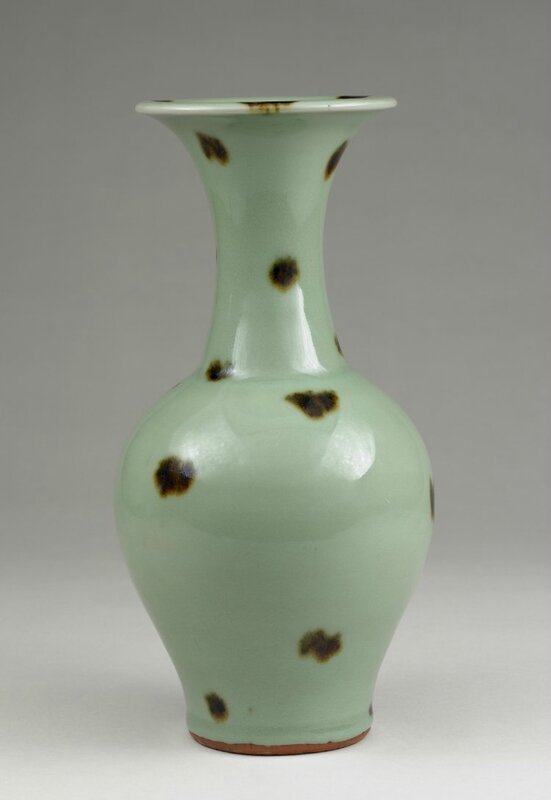

An extremely rare pair of Longquan tobi seiji garlic-mouth bottle vases, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

Lot 3133. An extremely rare pair of Longquan tobi seiji garlic-mouth bottle vases, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368); 10 in. (25.3 cm.) high. Estimate HKD 15,000,000 - HKD 25,000,000 (USD 1,943,282 - USD 3,238,802). Price realised HKD 12,060,000. Photo Christie's Images Ltd 2016.

Each vase is well potted with a compressed globular body rising from a splayed foot to a long slender neck ending in a garlic-head mouth, covered overall with a fine lustrous glaze of sea-green tone. The exterior is decorated with dark iron-brown splashes, boxes.

Provenance: Acquired in Taipei in the 1980s

Property from the Yangdetang Collection.

Exhibited: Tokyo Takashimaya, Kyoto Takashimaya, Osaka Takashimaya, Yokohama Takashimaya, MOA Museum of Art, Kure City Art Museum, Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum of Art, Two Thousand Years of Chinese Ceramics, 9 April 1992 - 23 November 1992 (travelling exhibition), Catalogue, pl. 57

Note: The present pair of garlic-mouth vases belong to a group of important type of Longquan ware decorated with ironbrown spots which has been much admired by the Japanese and is usually known by its Japanese name tobi seiji. Tobi seiji is famed for its rarity- there has been only a handful of tobi seiji vases published. These two tobi seiji vases are the only known examples that still remain as a pair, making them highly desirable. The beauty of tobi seiji lies primarily in the rich dark brown spots that create a striking visual impact on the otherwise subtle celadon surface. In fact, the name tobi seiji, literally ‘flying [spot] green ware’ in Japanese, was given by ancient Japanese tea masters for the dramatic appearance of iron spots (Kobayashi Hitoshi, ‘Research on National Treasure Tobi Seiji Vase’, Longquanyao ciqi yanjiu, Beijing, 2013, p. 404). Such spots were added, using a brush, to the surface of the unfired glaze before the pieces were fired. These seemingly spontaneously added spots in fact follow a very thoughtful design principle. As seen on the present examples, the iron spots were arranged in seven alternating bands of two or three spots from the mouth to the lower body, adding up to 19 spots in total on each vase. Upon closer examination, we can also see that many of these spots were painted with more than one brush stroke to create an overlapping texture. Celadon wares embody the ultimate serenity in the natural world. On the contrary, iron spots impose an impression of dramatic movement. The juxtaposition of these two contradictory elements was a bold experiment, yielding a harmonious outcome. The paradox that the timeless beauty of celadon can be synthesized with volatile ‘flying spots’ might account for the enduring fascination with tobi seiji. It is also interesting to note that the unglazed foot rim, which turned reddish-brown at the end of firing cycle, adds another layer of colour contrast to the piece, and therefore further enhances its beauty (see Kobayashi Hitoshi, ibid, p. 404).

Only one other vase of similar shape and decoration, measuring 28.2 cm. high, appears to have been published. This is registered in Japan as Important Cultural Property and now belongs to the Ise Cultural Foundation, illustrated in Masterpieces of Chinese Ceramic Art Exhibition: Treasure of Ise Collection, Tokyo, 2012, pp. 54-55, no. 41 (fig. 1).

fig. 1 A tobi seiji garlic-mouth vase, the Ise Collection, image courtesy of the ISE Cultural Foundation.

In addition, a broken tobi seiji vase of this form was found in the Ichijo-dani Asakura family historic ruins in modern-day Fukui prefecture (fig. 2). The Ichijo-dani castle is the base of the Asakura family, which was destroyed by the army of Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) in 1573. The last head of the Asakura family, Yoshikage Asakura (1533-1573) was known for his cultural refinement and was proficient in tea ceremony. The Song/Yuan ceramic sherds including the tobi seiji garlic-mouth vase found in the Ichijo-dani site are believed to belong to this illustrious Daimyo. This is a testament to the high regard to which tobi seiji vases of the present type were held in ancient Japan.

fig. 2 A tobi seiji garlic-mouth vase, storaged by Fukui Prefecture Board of Education, image courtesy of the Ichijodani Asakura Family Site Museum & Fukui Prefecture Board of Education

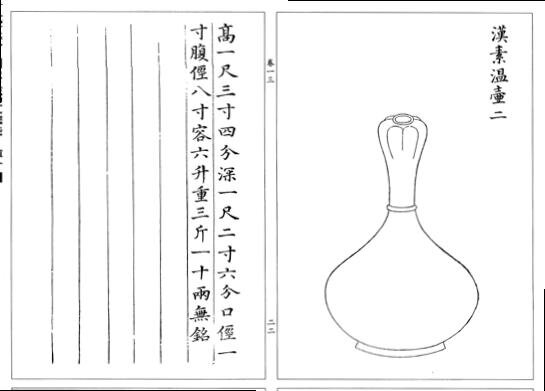

As a form, Longquan celadon garlic-mouth vases are rare. One such vase is from the Sir Percival David Collection, London, illustrated by Margaret Medley, Illustrated Catalogue of Celadon Wares in the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, London, 1977, p. 32, no. 96. Two Longquan garlic-mouth vases, one plain with only two moulded bow-string bands and one moulded with floral motifs, were among the cargo of over 18,000 ceramics in the Sinan wreck, which foundered off the coast of Korea en route for Japan in AD 1323 (illustrated in Relics Salvaged from the Seabed off Sinan, Seoul, 1985, pp. 38-39, nos. 31 & 32). Also among the Sinan cargo are two bronze garlic-mouth vases, illustrated in ibid, pp. 145 & 152, nos. 145 & 219. The former example is decorated with archaistic motifs and the latter is cast on the base with a four-character sealscript inscription Yi er zi sun (befitting for your sons and grandsons). Antiquarianism is a prominent theme in Song/Yuan art. Ceramics and bronzes of Song/Yuan period drew inspiration from archaic bronzes that were collected and published by scholar-officials and Emperors of the time. The garlic-mouth vase was a popular form on Han-dynasty bronzes and line drawings of such pieces can be found in the catalogue of Emperor Huizong’s archaic bronze collection, Xuanhe bogu tu (Illustrated Catalogue of Antique Objects in the Xuanhe era). (fig. 3) The present vases and other Longquan garlic-mouth vases not only followed the Han bronze form but also faithfully copied the bow-string decoration around the neck and wide body. It appears that the garlic-mouth vase was absent from the repertoire of Song-dynasty ceramics. However, this revived form was proven to be successful as it appeared with greater frequency on ceramics in the succeeding Ming and Qing dynasties.

fig. 3 Illustration of a Han-dynasty bronze garlic-mouth vase in Xuanhe bogu tu

Vases of the present type are used as flower vases during Japanese tea ceremony. The Japanese term for vases ?? (flower nurturer) refers to vessels that can hold flowers and keep them growing (see Kobayashi Hitoshi, ‘Research on National Treasure Tobi Seiji Vase’, Longquan qingci yanjiu, Beijing, 2013, p. 407). This concept actually originated in Ming China. Cao Zhao, in his classic text on connoisseurship, Gegu yaolun (The Essential Criteria of Antiquities), compiled in 1388, states that: “Ancient bronzes were buried underground for a long time and absorbed the qi of earth. Using them to grow flowers could accelerate blooming and postpone fading. Even if the flower fades, it can still bear fruit.” From this text we learn that the practice of growing flowers in vases was popular among Ming-dynasty connoisseurs. And in Song/Yuan China, garlic-mouth vases of the present type as well as bronze versions were most likely placed in a scholar’s studio to demonstrate their antiquarian taste. It is interesting to note that in the Xuanhe bogu tu, the Song-dynasty scholar describes the bronze garlic-mouth vases as wenhu ?? (warming bottle), and interprets their function as warmers for hands and feet. This, however, has very little impact on the function of such vases in Song/Yuan period as they were already regarded as antiques rather than practical utensils.

Other forms of tobi seiji vases include yuhuchun vases, fengweizun (phoenix-tail vases), twin-handled vases, and facetted meiping. Four tobi seiji yuhuchun vases are known: one in the Oriental Ceramics Museum, Osaka, registered as National Treasure; and one in a Japanese private collection, registered as Important Cultural Property, illustrated respectively in Koyama Fujio, ed., Sekai toji zenshu: China Sung and Liao Dynasties, vol. 10, Tokyo, 1956, pls. 17 (fig. 4) and 49; one in the Baur Collection, Geneva, illustrated by John Ayers, Chinese Ceramics, vol. 1, no. A104; and another in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, illustrated by William Bowyer Honey, The Ceramic Art of China and Other Countries of the Far East, London, 1945, pl. 36. There are two tobi seiji fengweizun, one from the Sir Percival David Collection, London, illustrated by Rosemary E. Scott, Imperial Taste: Chinese Ceramics from the Percival David Foundation, San Francisco, 1989, p. 47, no. 22 and the other in Ishibashi Museum of Art, Fukuoka prefecture, illustrated in Kobayashi Hitoshi, ‘Research on National Treasure Tobi Seiji Vase’, op. cit., p. 410, fig. 19. Examples of tobi seiji twin-handled vases include one in a Japanese private collection, illustrated in ibid, p. 410, fig. 22 and another in Shanghai museum, illustrated in Zhu Boqian, Celadons from Longquan Kilns, Taipei, 1998, no.155. Examples of facetted meiping with moulded ‘eight immortals’ design include one example in in a Japanese collection, illustrated in Sekai toji zenshu: Liao Jin Yuan, vol. 13, Tokyo, 1981, pp. 44-45, no. 32; one in the Palace Museum collection, illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan: taoci juan, Taipei, 1993, p. 356, no. 626; and one sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30 November 2011, lot 3010. It is important to note that although tobi seiji is most treasured in Japan, such wares were also highly valued in China, as evidenced by their presence in the Qing Court Collection, such as the a fore mentioned meiping in the Palace Museum, Beijing, and a tripod flower stand and a pouring vessel in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, illustrated in Gugong cangci: Longquan yao, Hong Kong, 1962, p. 54, pl. 14, and p. 66, pl. 21.

fig. 4 A tobi seiji pear-shaped vase, yuhuchunping, Ataka Collection, The Museum of Oriental Ceramics Osaka, National Treasure, Tobiseiji Hanaike, Photo: Tomohiro Muda

A tobi seiji pear-shaped vase, yuhuchunping, Yuan dynasty. Bauer Collection Geneva.

Stoneware bottle with iron spot decoration and green 'celadon' glaze, Longquan ware, China, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368). Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund, the Vallentin Bequest, Sir Percival David and the Universities China Committee, C.24-1935 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2016.

Vase with spotted glaze, Longquan ware, Yuan dynasty, about AD 1300–1368. On loan from Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, PDF 217 © Trustees of the British Museum

Vase, celadon, decorated with iron brown spots, Yuan dynasty, 14th century, Porcelain Important Cultural Property, Ishibashi Museum of Art, Fukuoka prefecture.

An important tobi seiji-decorated and moulded Longquan celadon 'eight immortals' octagonal meiping, Yuan dynasty, 14th century. Price Realised HKD 6,020,000 (USD 776,436) at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30 November 2011, lot 3010. Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2011.

Christie's. Chinese Ceramics From The Yangdetang Collection, 30 November 2016, Hong Kong, HKCEC Grand Hall

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F33%2F87%2F119589%2F29574209_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F80%2F35%2F119589%2F129054014_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F49%2F119589%2F128568387_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F01%2F119589%2F128506659_o.jpg)