New world record for Tibetan sculpture at Bonhams Images of Devotion Sale in Hong Kong

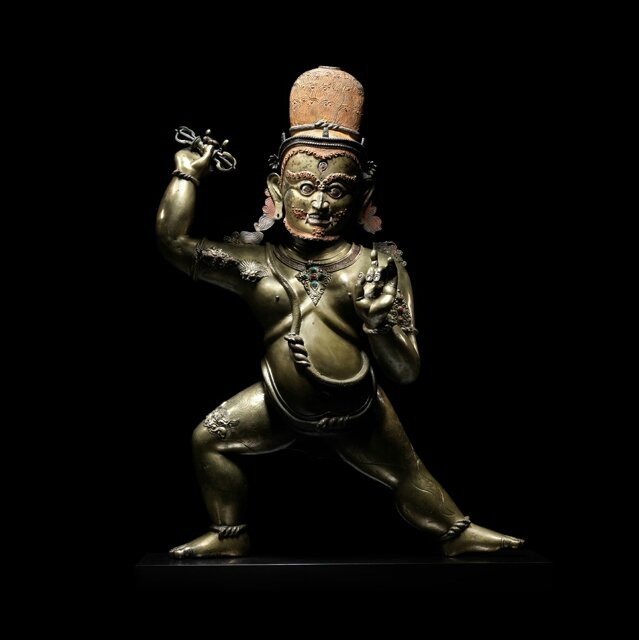

Lot 108. A monumental brass alloy figure of Canda Vajrapani, Tibet, 13th century. Estimate HKD 22,000,000 ~ 28,000,000. Sold for HK$ 49,260,000 (€5,971,705), a new world record price for a Tibetan sculpture. Photo: Bonhams.

HONG KONG.- An imposing brass Figure of Canda Vajrapani from the collection of Ulrich von Schroeder set a new world record price for a Tibetan sculpture at auction when it sold for HK$ 49,260,000 (US$ 6,351,479) at Bonhams Images of Devotion Sale in Hong Kong on 29 November. After a nine- minute bidding battle in a packed auction room, the figure was sold to an Asian collector. In total, the sale made more than HK$ 110,000,000 (US$ 14,182,275).

At more than a metre tall, the monumental Figure of Canda Vajrapani (in English, ‘fierce holder of the thunderbolt’) is one of the great masterpieces of 13th-century Tibetan sculpture and the most important surviving Tibetan brass sculpture of any period. It had an estimate of HK$ 22,000,000-28,000,000 (US$2,800,000-3,600,000).

Lot 108. A monumental brass alloy figure of Canda Vajrapani, Tibet, 13th century. Estimate HKD 22,000,000 ~ 28,000,000. Sold for HK$ 49,260,000 (€5,971,705), a new world record price for a Tibetan sculpture. Photo: Bonhams.

Hollow cast in six parts assembled with copper rivets, with copper inlay to the central rims of the crown and necklace, and to the finger and toenails, the jeweled ornaments inset with later turquoise and coral, the face and hair painted with applied cold gold, white, and orange pigments, the back sealed with a copper consecration plate. 1.04 m (3 ft. 4 in.) high

Provenance: Collection of Ulrich von Schroeder

Acquired in London, 1995

Over a meter tall, this monumental figure of Canda Vajrapani (lit. 'Fierce Vajrapani') is without doubt one of the great masterpieces of 13th-century Tibetan sculpture, and the most important surviving Tibetan brass sculpture of any period. In quality and scale, it ranks among some of the most iconic and famous early Himalayan sculptures, such as the 'Zimmerman Buddha' now held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (acc. #2012.458), and the 'Rockefeller Gilgit Shrine of Crowned Buddha' at Asia Society, New York (acc. #1979.044).

There is only one large metal sculpture of Vajrapani to compare in Tibet, currently in the custody of Shalu monastery and found on the ground floor of the Serkhang (or 'Golden Temple'). However, it does not withstand comparison, as the Serkhang Vajrapani is quite smaller (84cm, figure), of lesser sculptural quality, and much damaged. Rather, in detail and overall effect, the von Schroeder Vajrapani reflects the highest artistic standards of Tibetan metal sculpture.

Achieving such a large work in cast metal requires great skill and experience, especially at the high altitude of the Tibetan plateau, where casting becomes more volatile. To compensate for these conditions, monumental sculptures were typically cast in separate parts and assembled afterwards. This technique is most noticeable on the von Schroeder Vajrapani's reverse, where the original copper rivets can be seen along the crease of his backside. However from the front, the joints of the arms, legs, and neck are hidden, and the sculpture appears as a seamless single casting, a testament to sculptor(s) expertise.

Another remarkable feature is the sculpture's copper inlay, forming the central band of his diadem and the torque around his neck. Perhaps most alluring though is the thick and glossy application to the nails of its fingers and toes. The inclusion of copper inlay frequently distinguishes superior Himalayan bronzes from those of lesser quality, but there are few large-scale examples from 13th-century Tibet to compare to. Meanwhile, it is easier to trace the technique's origin in the sculptural traditions of Kashmir and Eastern India that bore influence on Tibet, as epitomized in a magnificent 11th-century Western Tibetan sculpture of Manjushri in the Jokhang, Lhasa. Of similar size to the von Schroeder Vajrapani, general similarities can be drawn between the first inlaid band of his lower garment, engraved with chevrons, and his inlaid finger- and toenails.

But while few direct comparisons with large metal sculpture from the same period can be made, drawing on depictions in other mediums locate the von Schroeder Vajrapani within the 13th century. Numerous extant paintings have allowed scholars to frame a stylistic chronology around keystone pieces dated by inscription or historical sources. A 13th-century painting of Vajrapani within a folio from a Prajnaparamita manuscript held by the Rubin Museum of Art depicts his hair arranged in the same manner, as a single curved bun with tresses unfurling on his shoulders (Linrothe & Watt, Demonic Divine, New York, 2004, pp.224-5, no.54: detail). His bulging eyes and orange facial hair are also conceived similarly to the von Schroeder Vajrapani, as are his burgeoning thighs and the fleshy fold below his pectorals. These characteristics are also present in a depiction of Vajrapani within a 13th-century thangka of Shakyamuni. It also matches the particular treatment of the von Schroeder Vajrapani's thin flame-like beard, and three-leaf crown terminating either side with small flowers (Kossak & Casey Singer, Sacred Visions, New York, 1994, pp.87-8, no. 16: detail).

The von Schroeder Vajrapani is the most spectacular metal sculpture of one of Buddhism's primary protector deities. Each cast component seems stretched to its full capacity to emphasize his overwhelming build and power. Greater than what we see in these two painted examples, its massive proportions compare to an important large stone stele of Vajrapani carved at Feilaifeng in Hangzhou between 1281-1292, during the Yuan dynasty. However, the stylistic restraint shown in the von Schroeder Vajrapani's jewelry and its relatively sparse placement leaves the viewer to focus on his immensity in a way that the ornate trappings of the Feilaifeng Vajrapani distract from. This simplicity of adornment allowing more emphasis for spirit and vitality constitutes a core characteristic of early Tibetan sculpture that has made it so prized among connoisseurs of Himalayan art.

The origins of Vajrapani (lit. 'holder of the thunderbolt') can be traced back to the far reaches of human civilization, evolving from the Indian Vedic deity Indra, first mentioned in ancient hymns dating approximately between 1700-1100 BCE. Indra is the King of Heaven and the bringer of rains, the main life source in India, brandishing the thunderbolt during storms. As Buddhism spread and competed with other religions, it absorbed key pre-existing deities to invite broader congregations. Indra was incorporated into the Buddhist pantheon in the first centuries CE as a bodhisattva, an attendant of Buddha. As Monika Zin has shown, Vajrapani appears in Indian art around the late 2nd century, frequently accompanying Buddha in narrative scenes of conversion, particularly involving violent or stubborn individuals, such as the raging elephant Dhanapala and the heretic Nanda (Zin, "Vajrapani in the Narrative Reliefs", in Migration, Trade and Peoples, Part 2: Gadharan Art, London, 2005, pp.73-83). In later Gandharan and Gupta sculptures of the 4th-6th centuries, he frequently appears on the left side of Buddha in a triad with Avalokiteshvara. While still recognizable by the vajra he wields, this overhaul of Indra's appearance and purpose proved an effective way for early Buddhism to appeal to and incorporate devotees who revered the Vedic deity.

However, by the 13th century, Vajrapani's role and appearance was reshaped by tantric thought emerging between the 6th-12th centuries in a process described in great detail by Rob Linrothe (Ruthless Compassion, London, 1999). He is transformed from a yaksha spirit-attendant into a prominent protector deity in his own right, safeguarding Buddhism's teachings and community in his popular 'fierce', 'wrathful', or 'impassioned' form (skt. Canda/Krodha). He wields Indra's thunderbolt, now a 'diamond scepter' having the capacity of piercing and penetrating almost all materials and mindsets. He represents the combined power of all the Buddhas and acts as the remover of both internal and external obstacles to Buddhism and its practitioners. One must remember that in the Vajrayana context wrathful imagery is not meant to represent anything malign or demonic, but to express the invincible power of compassion.

His large belly, bulging limbs, and disproportionally large head, convey a dwarfish appearance that betrays Vajrapani's ancestry as a yaksha in Indian Buddhism. In the Sadhanamala, an important Vajrayana treatise on iconography composed between the 5th and 11th centuries, Vajapani is referred to as a yaksha general. With his left leg fully cocked, he leans on his right knee in 'warrior pose' (pratyalidha), while brandishing the thunderbolt like a deadly weapon above the devotee, and displaying the gesture of exorcism with his left hand (karana mudra). Heightened by the contrast between the applied orange and cold gold paint, his expression bears such ferocity that there is never any doubt he would subdue whatever threatened the practitioner. His bulging eyes stare intently while he confidently grimaces, baring sharp fangs at the corners of his mouth. His facial hair and chignon with orange pigment evoke flames, alluding to fire's symbolic power to consume and transform, like Vajrapani's capacity to purify negative ailments obstructing the practitioner.

Vajrapani's origins are also alluded to here in the eight docile snakes wrapped around the sculpture's chignon, armlets, bracelets, anklets, belt, and sacred cord. In the Indian and Himalayan cultural context, snakes, known as naga, are closely associated with winding rivers, monsoons, and water. Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism incorporated the snake as a semi-divine being, sometimes using it as a pictorial device to form a protective seat and hood for the principal deity, as seen in episodes of Buddha, Vishnu, and Parshvanatha. Subdued around his body, the snakes also represent Vajrapani's ability to quell harmful forces and poisonous emotions. The von Schroeder Vajrapani also wears a lower garment of a tiger skin, which reaches far into his Indian origins, associated with adharmic and fierce representations of the Hindu god Shiva. The tiger's face, appearing above his right knee, is one of the most impressive examples of Tibetan engraving.

This spectacular depiction of Vajrapani is one of the most daring Tibetan metal sculptures ever made. In its original ritual context, it would have likely featured on an altar of a primary monastery, probably within close vicinity of a large figure of Buddha. It would have been venerated daily, given ablutions and washed with purifying liquids, contributing to the beautiful smooth and glossy surface it has survived with. From the reverse, we can see a large copper plate, which would have been added at the final stage of its creation, after the placement of charged sacrificial gifts inside its hollow core and its ritual enlivening.

《Masterpieces of Himalayan Art from the Collection of Ulrich von Schroeder》. Essay by Jan Van Alphen, July 2016

Another masterpiece from Schroeder’s collection, a copper Composite Figure of Vajrapani and Kubera by the Tenth Karmapa Choying Dorje (1604-1674), sold for HK$ 15,060,000 (US$1,940,000) against an estimate of HK$ 13,000,000-18,000,000 (US$1,700,000-2,300,000). This key work, which bears the hallmarks of Choying Dorje’s whimsical style and visionary iconography, has been in the von Schroeder collection for more than 20 years.

Lot 110. A Copper Composite Figure of Vajrapani and Kubera by the Tenth Karmapa Choying Dorje (1604-1674). Estimate HKD 13,000,000 ~ 18,000,000. Sold for HK$ 15,060,000 (€1,825,697). Photo: Bonhams.

Figure: 14.3 cm (5 5/8 in.) high;

Travelling Shrine: 22 x 20.3 x 15 cm (8 5/8 x 8 x 5 7/8 in.)

Published: Adrian Maynard, "Advertisement", in Oriental Art, Vol. XXXIII, no.2, 1987, p.122.

Ulrich von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Volume Two: Tibet & China, Hong Kong, 2001, pp.740–6, 754–5, figs. XII–13, pl. 175; also illustrated on the spine, cover, frontispiece, and final illustration.

Irmgard Mengele, "The Life and Art of the Tenth Karma-pa Chos-dbyings-rdo-rje (1604-1674): A Biography of a Great Tibetan Lama and Artist of the Turbulent Seventeenth Century" (Dissertation), Universität Hamburg, 2005.

Hu Guoqiang, "Study of a Tibetan inscribed Guanyin Bronze Sculpture", in Sino-Tibetan Art Research. Proceedings from the Third International Symposium on Tibetan Archaeology and Art, Xie, Luo & Jing (eds), Shanghai, 2009, pp.389-395.

Irmgard Mengele, Riding a Huge Wave of Karma: The Turbulent Life of the Tenth Karma-pa, Kathmandu, 2012, p.369, pl. 2.

Karl Debreczeny (ed.), The Black Hat Eccentric: Artistic Vision of the Tenth Karmapa, New York, 2012, p.216, fig.8.2.

Bsod nams dbang ldan [Sonam Wanden], Potala Palace, Pho brang Po taa la, Pho brang Po taa la la'i do dam khru'u nas, nang khul lo phyed dus deb, spyi'i deb grangs I, II-23, Bod btsan po'i dus kyi li ma'i sku brnyan skor rob tsam gleng ba, 2012.

Ian Alsop, "The Sculpture of Chöying Dorjé, Tenth Karmapa", AsianArt.com, January, 2013, http://asianart.com/articles/10karmapa/

Ulrich von Schroeder, "The Sculpture of Chöying Dorjé, Tenth Karmapa: A Review", AsianArt.com, January, 2013, http://asianart.com/articles/10karmapa-uvs-review/index.html

Luo Wenhua, "A Survey of a Willow-branch Guanyin Attributed to the Tenth Karmapa in the Palace Museum and Related Questions", in The Tenth Karmapa & Tibet's Turbulent Seventeenth Century, Debreczeny & Tuttle (eds), Chicago, 2016, pp.168 & 178-9, fig.7.22.

Provenance: Adrian Maynard by 1986

Sotheby's, New York, 30 November 1994, lot 235

The wooden shrine acquired in 1996.

Having served for some 15 years as the gold foil emblem on the cover and spine of Ulrich von Schroeder's Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Volume II: Tibet & China, this enigmatic figure is one of Tibetan art's most famous sculptures. It has fascinated scholars, receiving at least three different attributions since 1987. First, it was described as a 7th-/8th-century Nepalese sculpture, due to its high copper content and glossy, worn patina. Then, it was heralded as one of the earliest surviving Tibetan sculptures from the long-lost Yarlung kingdom (c. 7th-9th centuries). And more recently, as further research has enriched our understanding of the incredible life and art of the Tenth Karmapa Choying Dorje (1604-1674), the figure has been identified as one of his key sculptures, the most important work bearing an inscription of his name in private hands.

It bears the hallmarks of Choying Dorje's beloved whimsical style and visionary iconography, smiling with his telltale puckered lips, bringing form to an otherwise expansive chin below a well-conceived but unruly hairstyle. The dwarfish and pot-bellied male copper figure is trampling on a snake (naga) placed on a single lotus stand with two Garuda-birds at the sides and supported by an oval, rock-shaped pedestal. Garuda, whose name is interpreted as "devourer", is the sworn enemy of the snakes. The figure holds a diamond scepter (vajra) in the right hand and a female mongoose (nakuli) in the left. This image is a composite figure of Vajrapani distinguished by the diamond scepter, and of Kubera, characterized by the mongoose. This deity thus integrates aspects of Vajrapani and Kubera. The image is sparsely dressed in a piece of cloth tied around the hips. He is wearing the "five seals" (pancamudra) ornaments, here composed of snakes (naga), namely a pair of earrings, a necklace, a pair of bracelets, anklets, and the investiture with the sacred thread in the form of an anthropomorphic Nagaraja (nagopavita) in addition to the tiny Nagarajas ("naga kings") behind the ears. Another pair of Nagarajas coils around the narrow waist of the pedestal. The composition of the pedestal relates to the episode where the multi-headed Naga Vasuki was tied around Mt. Mandara and used as the churning rope to churn the ocean of milk. This compositional feature is copied after brass statues of the Patola-Sahi of the Gilgit valley in Kashmir cast about 650–750 AD of which some were in the possession of the Tibetan temples since the Imperial Period in the 7th–8th centuries.

On the front side of the pedestal, along the lower edge, is a single-line dedicatory Tibetan inscription in dBu can script: || rje btsun chos dbyings rdo rje'i phyag bzo ||. "A work made by the venerable Chos dbyings rdo rje". Aligning it with the only seven known examples bearing such dedicatory inscriptions. Chief among them are two copper figures in the Jokhang, Lhasa, very similar to the present sculpture, such that they were likely produced at the same time. A high copper content, similar to Nepalese metal sculptures, is congruent across all three, although they are different in size and physiognomy. Interestingly, with exception of the image offered for sale, two evade any definitive identification in subject matter, combining iconographical elements unseen elsewhere, although it is hoped their secrets may be unlocked through further research of the Tenth Karmapa's biographies.

According to von Schroeder, this figure, and the two in the Jokhang, actually represent much earlier pieces which Choying Dorje drew artistic inspiration from – as he was known to do with ancient sculptures. Von Schroeder recognizes stylistic comparisons with Yarlung dynasty sculptures and woodcarvings, such as the yaksha-like proportions, ovoid face, and unruly hair of an atlant carved in a pillar at the Jokhang probably during the temple's construction in the 7th century. He also argues that the bronze's extensive wear indicates a much earlier date than Choying Dorje's lifetime, to which an inscription was added in the 17th century or later, possibly by someone who misinterpreted its resemblance to works by the Tenth Karmapa. He sees in its non-canonical iconography a nascent reconciliation between foreign Indian Buddhist and Brahmanical ideas and native Tibetan traditions.

Meanwhile, Ian Alsop and other scholars argue that since this bronze resembles the rest of Choying Dorje's oeuvre, it must belong to it. He views the unconventional iconography as entirely aligned with the Karmapa's visionary style. He surmises that the inscription is factually correct and was probably overseen by someone with an intimate knowledge of Choying Dorje's works, such as Pelden Gyats o (1610-1684). Also known as Kuntu Zangpo, Gyatso is mentioned as the recipient of the thangka, Marpa Receives the Poet-Saint Milarepa, preceding this lot. Alsop acknowledges that it seems hard to believe that the level of wear could have occurred in just 400 years, but he doesn't discount the possibility. Of course, the ongoing debate of whether an anonymous artist cast this image during the Yarlung dynasty, or Choying Dorje during the 17th century, merely affirms its significance as one of the most fascinating masterpieces of Tibetan metal sculpture. Either it stems from the birth of Tibetan art and had a seminal influence upon Choying Dorje, or it represents one of the most important sculptures by him.

Rubbed and worn to a smooth buttery patina, if we accept the sculpture as a creation by Choying Dorje, its extensive wear invites us to deduce that it must have had great personal significance for the Tenth Karmapa. Such wear is typically seen on devotional sculpture that is washed and rubbed during ritual and prayer, a practice that is particularly encouraged in Nepal, for instance. The extent seen here certainly rivals what one would typically associate with much older Nepalese sculpture. If it were made by Choying Dorje, and kept in his possession, he must have propitiated it frequently, perhaps more than daily. Its subject matter may begin to take on greater significance, combining the deities responsible for protecting devotees from harmful forces and providing sustenance. These were surely two perpetual concerns for Choying Dorje, and we may even be tempted to imagine the scars across the sculpture's ankles as being damaged and repaired along the Tenth Karmapa's perilous road to safety.

In fact, beyond the unique and charismatic appeal of the Tenth Karmapa's style, it is the potential to read his life story into his art that gives it such profound appeal among collectors, curators, and scholars. Whereas in Tibetan art, where artistic production is integrally anonymous and formulaic, Choying Dorje's biographies and oeuvre provide a rare, perhaps even singular, instance where it is possible to read the artist's struggles and worldview into his painting and sculpture.

Furthermore, the scholarly debates around the attribution of this sculpture have somewhat distracted from just how incredible and rare it is, distinct from hundreds of thousands of other Tibetan sculptures produced since the eighth century. it is important to first understand that every piece of Tibetan Buddhist art was made for worship. As such, in order for a sculpture to be ritually viable, it had to follow a set of prescriptions for what the Buddha, deity, or monk looked like: canonized descriptions of the posture and implements that identified him or her. Even the proportions had to follow strict iconometric rules in order for a painting or sculpture to be spiritually potent. Deviations were met with fierce objection. That is, with the notable exception of instances when they were inspired by the meditations or visions of a top-ranking lama, such as a reincarnate Karmapa.

Accompanying the sculpture is a rare 13th-century shrine. Lightweight and assembled of wood with painted decoration, it likely served as a travelling shrine during pilgrimages. The small temple with attached doors is painted on the inside with an altar dedicated to the triratna, a symbol for the three-fold nature of Buddhism: the Buddha, the teachings, and the monastic community. Two bodhisattvas, likely Manjushri and Avalokiteshvara, stand by either side of the altar embracing it with one arm. Flanking Garuda above are Shakyamuni and Samvara with his consort, Vajravarahi. The two side-panels each depict separate lineages illustrating the transmission of a particular tantric tradition. The left side possibly depicts a version of the Chakrasamvara lineage beginning with Vajradhara and the mahasiddha Saraha. The right side depicts a version of the Lamdre tradition beginning with Vajradhara, Nairatmya, Virupa, and Kanhapa. The pointed upper corners of each figure's throne back is a stylistic convention generally seen before the 14th century. Whilst purchased separately, for twenty years this shrine has sheltered this enigmatic sculpture in Ulrich von Schroeder's home, as they appear together in the first and last illustrations of Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Volume II.

《Masterpieces of Himalayan Art from the Collection of Ulrich von Schroeder》

Commenting on the sale, Bonhams Global Head of Indian, Himalayan Art & Southeast Asian Art, Edward Wilkinson, said, “Ulrich von Schroeder is rightly regarded as the pre-eminent scholar in the field of Tibetan sculpture. This opportunity to acquire pieces from his personal collection led to intense competition in the saleroom and on the telephone and online. The stunning price paid for the figure of Canda Vajrapani reflects both its high importance as a work of art and von Schroeder’s great standing among collectors.”

Other highlights included:

Lot 111. A large gilt copper figure of Avalokiteshvara, Nepal, Thakuri period, 10th century. Estimate HKD 12,000,000 ~ 16,000,000. Sold for HK$ 15,660,000 (€1,898,434) to a collector in the US. Photo Bonhams.

With inlaid semi-precious stones and remains of blue pigment in the hair.

Himalayan Art Resources item no.2118

59.4 cm (23 3/8 in.) high

Provenance: Private Collection, acquired in Europe in 1990.

This svelte Nepalese figure of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion in Mahayana Buddhism, is a rare and important example of Thakuri-period craftsmanship (9th-12th centuries) in all aspects of modeling, casting, gilding, and insetting of precious stones. It compares directly, in scale and style, to a small group of gilt copper statues found in monasteries and palaces in Tibet that were cast by the highly skilled Newari artists of the Kathmandu valley.

The Bonhams Avalokiteshvara stands on a circular platform. Two tenons projecting from the underside would have inserted the sculpture into a separate metal or wood base. He is modeled in a gently bent pose (abhanga). His right hand is held down in the gesture of boon giving (varada-mudra), and shows an engraved circular mark in the palm. His left hand, bearing the same mark, is executed in the "ring-hand gesture" (kataka-mudra), with thumb and index forming a ring-shaped opening in which an attribute can be inserted. Seen among similar sculptures, the stem of a separately cast white lotus (padma) would have likely passed through it and flowered by his left shoulder. As such, the sculpture almost certainly represents Avalokiteshvara in the form of Padmapani, the 'lotus-bearer' (Tib. Phyag na padmo).

He is clad in a loincloth engraved with curved lines evoking the stripes of a tiger skin and yantra or shrivatsa (endless knot) patterns. The garment is secured with a belt around the hips and the folds draped between the legs. He also wears a sash diagonally around the thighs, the knot and its V-shaped ends hanging down on his left side. He has bejeweled ornaments inset with clear red, blue, and green garnets, and rock crystal, following the early Nepalese tradition. Later on, as Tibetan patrons favored turquoise and coral, Newari artists started to exchange the once translucent stones for opaque pieces of turquoise, lapis lazuli, and coral.

His bejeweled ornamentation is plentiful and yet restrained compared to later examples. His inset armbands are worn high above the biceps leaving his lissome arms swaying unencumbered until simple ring-shaped bracelets adorn his wrists. Meanwhile, an effigy of seated Amitabha occupies the center of his tall and elaborate three-leaf crown. Its band consists of a double-beaded diadem with two round flowers fixed above the ears. Meanwhile, remains of blue pigment within recessed areas of his hair indicate he was once worshipped in Tibet.

A sacred thread (yajnopavita) descends over his left shoulder with a red garnet on the clasp under the left nipple. Important for dating the sculpture, this thread forms a little loop over the sash, before being tucked under it and continuing across the right thigh and returning across the back to the shoulder. This distinctive loop seems to appear only in sculptures dating to the Thakuri period, in and around the 10th century.

Examples demonstrating this include two very differently styled standing bodhisattvas in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York – one a 10th-century example of Avalokiteshvara more akin to the previous Licchavi style (5th-8th centuries), the other an 11th-century Maitreya with a more elaborate sway that seems to foreshadow later bronzes of the Early Malla period (13th-14th centuries). By the 12th century the loop disappears, as witnessed in an example of Avalokiteshvara held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc.#1982.220.2) and a badly damaged yet monumental bodhisattva in the Rubin Museum of Art. By far the closest direct comparison to the Bonhams Avalokiteshvara, however, is held in the Tibet House Museum, New Delhi likely produced at the same atelier around the same time, and also displaying this distinctive yajnopavita loop.

Avalokiteshvara's origins are quite elaborate and complex. His name first appears in textual sources from the beginning of the Common Era. Observed in the early Buddhist art of Ancient Gandhara, he gradually replaces the Vedic god Brahma as an attendant of Buddha Shakyamuni and inherits Brahma's attribute, the white lotus. He adopts the name Padmapani Lokeshvara, 'The Lord of the World Holding the Lotus'. But the messianic Mahayana Buddhist literature call him Avalokiteshvara, 'The Lord Who Looks Down [with Empathy]', viewed as the ultimate being of compassion, which is the highest virtue in Mahayana Buddhism.

Conceived as the spiritual son of the Transcendental Buddha Amitabha (lit. 'Infinite Light'), who is regularly presented in his crown or hair, Avalokiteshvara reached enlightenment but waits to dissolve forever into nirvana. He has first vowed to guide and liberate all sentient beings from the bondage of death and rebirth, with all its inherent suffering. These are not only human beings, but also gods, animals, spirits, and demons.

The essence of his compassionate nature is expressed in the mantra 'om mani padme hum' an invocation of the deity, 'Oh, Jewel-Lotus' (though usually translated as "Om, the Jewel in the Lotus, Hum"). The mantra is recited millions of times a day, and every bead of the Buddhist rosary (japamala), or every turn of the prayer mill invokes Avalokiteshvara's help and compassion.

The cult of Avalokiteshvara spread rapidly by the 1st century, where in China he became known as Guanshiyin, 'Perceiver of the Sounds of the World', or more briefly Guanyin, 'Perceiver of Sounds'. Guanyin subsequently became Kannon in Japan and Kwanum in Korea. As in the case of the Heart Sutra (Prajnaparamitahrdayasutra), Avalokiteshvara is the chief protagonist and converser in many important Mahayana sutras. He transcends all limitations of material, place, and time, and on occasion receives greater veneration than the Buddha.

In Tibet, Avalokiteshvara is called Chenrezi (Tib. Spyan ras gzigs). He is the patron deity of Tibet. Its spiritual and political leaders are his incarnations, such as Tibet's first Dharma king Songsten Gampo (604-650, Tib. Srong Btsan Sgam Po) and the Dalai Lamas. The Potala palace in Lhasa is named after his paradisiac abode, Potalaka.

Returning to the Bonhams Avalokiteshvara, the 10th-century Nepalese sculpture has all the characteristics of the idealized Bodhisattva represented as an attractive young male with princely attire. The elegant arrangement of his jewelry leaves much of the body bare, revealing the supple contours of his slender torso. His attitude and facial expression invoke admiration, compassion, and peace. The Newari artists were masters in doing so. Despite surviving for more than 1,000 years, the Bonhams Avalokiteshvara appears eternally youthful, like the Bodhisattva.

Essay by Jan van Alphen, September 2016

Lot 132. A gilt copper alloy shrine to Vajrabhairava, Tibet, 18th century. Estimate HK$ 800,000-1,200,000. Sold for HK$ 4,020,000 (US$520,000). Photo Bonhams.

Himalayan Art Resources item no.2147

22.8 cm (9 in.) high

Provenance: Sotheby's, London, 2 December 1968, lot 14

Private European Collection, thence by descent

Notes: Among the fertile collaboration between the imperial court of China and monastic seats of power in Tibet a tremendous volume of Buddhist sculpture was commissioned for exchange and presentation. Tashi Lhunpo, in Central Tibet, was considered the most powerful and influential monastery in the 18th century. Similarly, Dolonnor Monastery in Inner Mongolia, established in 1701 as the summer residence of the Gelug spiritual regent in Inner Mongolia, the Changkya Hutuktu, became a major center of production for Buddhist sculpture and painting.

The masterful execution of this powerful composition suggests strong Newari influences catering to the Qing imperial taste. The single row of long, rounded lotus petals and a thick beaded upper rim match the base of a Hayagriva published in von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, p.455, no.125D-E, as well as the lotus petals found on a Nepalese Indra (ibid., p.384, no.104A). These examples indicate Newari workmanship beyond the Kathmandu Valley. As does another 18th-century Hayagriva in the Musée Guimet, that is stylistically very close, with a more elaborate flaming arch and narrower lotus pedestal (ibid., p.455, no.125F).

Additionally, the incised visvavajra on the consecration plate is gilded following a tradition that is favored by the atelier of Zanabazar in Outer Mongolia within the 17th and early 18th centuries. While there was a tradition in Tibet of fully gilded consecration plates, this Zanabazar school idiom of a separately gilded visvavajra may suggest that the Newari artists once thought to have worked in Mongolia, travelled afterwards to take up special projects at thriving monasteries such as Tashi Lhunpo. Compare the modeling of the broad curling lotus leaves found on a Mongolian Jinasagara-Avalokitesvara published in Jinshen, Eternal Wisdom: Collection of Gilt-Bronze Buddhist Sculptures from the Hall of Harmony, Beijing, 2011, p.235. Both sculptures also share the same treatment of jewelry, beaded festoons, and garlands of heads.

A near-identical, slightly smaller sculpture was recently sold at Sotheby's, New York, 16 March 2016, lot 745. Other related examples, united by a common treatment of the flaming aureole, are held in Rehol Monastery, Chengde and the Qing Palace Collection, Beijing, published in Hsu, Buddhist Art from Rehol, Taipei, 1999, p. 97, no. 29, and Wang (ed.), Zangchuan Fojiao Zaoxiang, Hong Kong, 1992, p.92, no.64, respectively.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F94%2F119589%2F128705688_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F88%2F119589%2F127649882_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F41%2F75%2F119589%2F126978834_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F51%2F119589%2F126856859_o.jpg)