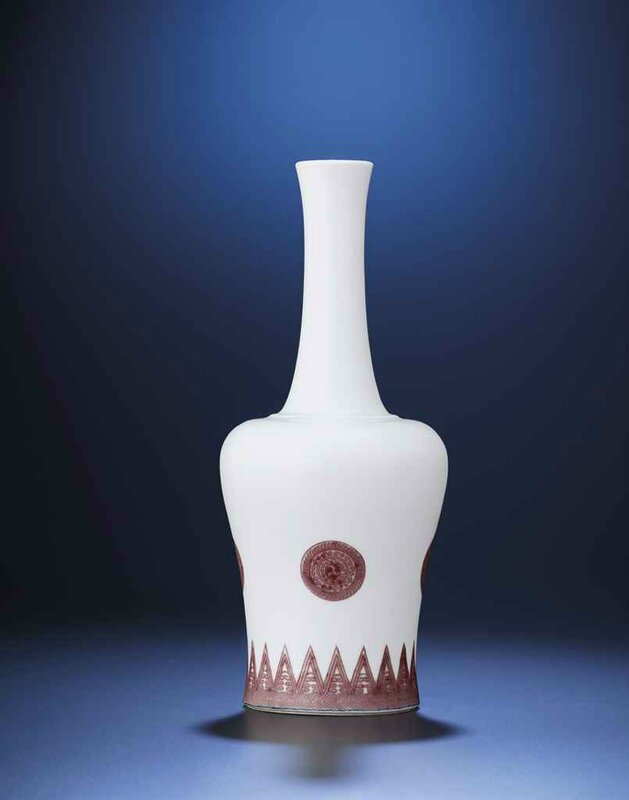

A fine and rare underglaze copper-red 'mallet' vase,yaoling zun, Kangxi six-character mark in underglaze blue and of the period

Lot 2936. A fine and rare underglaze copper-red 'mallet' vase,yaoling zun, Kangxi six-character mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1662-1722). Estimate 15,000,000 - HKD 20,000,000 (USD 2,000,000 - USD 2,600,000). Price realised HKD 11,860,000 (USD 1,529,655). Photo: Christie's Images Ltd. 2011.

Exquisitely potted with high shoulders tapering towards the foot, finely decorated in a soft copper-red with four roundels positioned above a band of upright blades rising from a herringbone band divided and outlined by fine lines in underglaze blue, the tall gently flaring neck rising from a bow-string band at its base - 9 in. (22.8 cm.) high

Provenance: Important Chinese Ceramics from the J. M. Hu Family Collection, sold at Sotheby's New York, 4 June 1985, lot 20

Previously sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 29 October 2000, lot 14

Note: Vases of this rare form appear decorated both in underglaze cobalt-blue and also, like the current example, in underglaze copper-red with underglaze blue lines encircling the base. Both types have underglaze blue six-character Kangxi marks.

The elegant form of these vases, with their long, slender, slightly waisted necks rising from pronounced shoulders, is particularly associated with the Kangxi reign. In Chinese the name often given to this form is yaoling zun, or 'hand bell vase'. The reference is to bronze bells, which formed part of the repertoire of Chinese instruments used in formal secular and religious music, although pottery bells of similar, if less refined form, were made in China as early as the Neolithic period. A greater number of ceramic bells were made during the Warring States period, and the body of the current porcelain bell is close in form to some of the large, handsome, glazed stoneware bells made in Zhejiang province, such as the example in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco illustrated by He Li, Chinese Ceramics, London, 1996, p. 68, no. 41.

However, in English the form is usually called mallet-form, in reference to earlier ceramic vases which took their shapes from mallets or paper-beaters. Song dynasty vases of this type, known as zhichui ping (paper-beater vase), which were particularly admired, were those of Ding ware (see Song Ceramics - Objects of Admiration, Percival David Foundation, London, 2003, pp. 20-21, no. 1) and Ru ware (see Porcelain of the National Palace Museum - Ju Ware of the Sung Dynasty, Hong Kong, 1961, pp. 30-31, pls. 3a & 3b; and pp. 32-33, pls. 4a & 4b).

However, the sides of the Kangxi porcelain form are slightly concave, in contrast to the convex sides of the Song wares, which are closer in shape to the wooden paper-beaters. In fact, the Kangxi vases are also more attenuated, and the yaoling zun seems to have been a new addition to the Qing dynasty porcelain repertoire in the Kangxi reign and was rarely seen thereafter. It has been noted by the British scholar John Ayers, in discussion of a similar vase decorated in underglaze cobalt-blue, that the form of these yaoling zun resembles in form the white Lamaist pagodas of Mongolia and Tibet. See J. Ayers, Chinese Porcelain: The S.C. Ko Tianminlou Collection, part II, Hong Kong Museum of Art, 1978, p. 76, no. 49. The vase is particularly close in form to that of the White Pagoda of the Lamaist temple in Beihai Park in Beijing, which was originally built in 1651 under the Shunzhi Emperor, but following its destruction in an earthquake in 1679, was re-built by the Kangxi Emperor in 1680.

It is not surprising to find that forms influenced by Lamaism or Tibetan Buddhism should be found amongst the porcelains of the Kangxi period. In his youth the Kangxi emperor was much influenced by his grandmother the Grand Dowager Empress Xiaozhuang, who was both a Mongol and a Lamaist Buddhist. Kangxi also compared himself, somewhat disingenuously, with a reincarnation of Kublai Khan in his relationship with his Tibetan Buddhist preceptor, Phagspa. During Kangxi's reign ten Chinese Buddhist monasteries were converted into Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. The Kangxi emperor built the Bishu shanzhuang at Chengde which was used as a retreat from the summer heat of Beijing and for hunting, but also to provide a more relaxed atmosphere in which to meet Mongol and Tibetan chieftains. In the area of Chengde Kangxi also built monasteries, and the great monastery at Dolonar was built near Beijing, which became designated as the centre for Buddhism for South Mongolia. Interestingly, some of the policies adopted by Kangxi were known as 'respecting the Dalai Lama in order to pacify Mongolia'.

Christie's. Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, 30 November 2011, Hong Kong

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F70%2F49%2F119589%2F113206633_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F41%2F99%2F119589%2F112963826_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F83%2F119589%2F112309628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F41%2F119589%2F112288255_o.jpg)