2 janvier 2017

Deer Mandala of Kasuga Shrine, Japan, Nanbokuchō period (1336–92), late 14th century

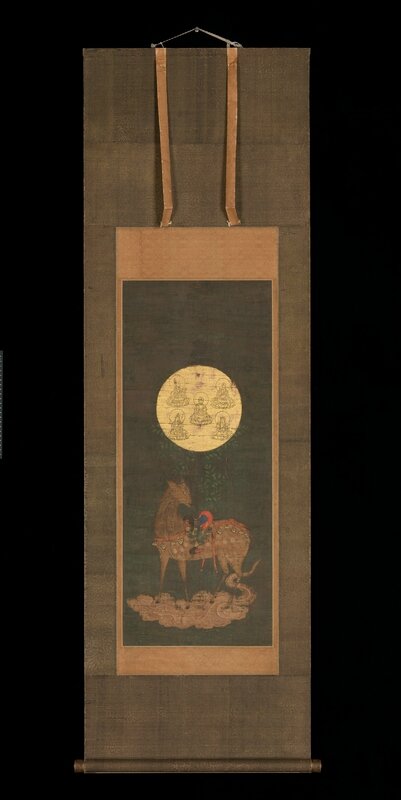

Deer Mandala of Kasuga Shrine, Japan, Nanbokuchō period (1336–92), late 14th century. Hanging scroll; color on silk. Image: 33 15/16 × 13 7/8 in. (86.2 × 35.2 cm) Overall with mounting: 66 15/16 × 20 15/16 in. (170 × 53.2 cm) Overall with knobs: 66 15/16 × 22 15/16 in. (170 × 58.2 cm). Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015, 2015.300.11 © 2000–2016 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A spotted brown deer, bedecked in a sumptuously decorated saddle and gold pendants dangling from a vermilion harness, looks back over its shoulder, as if interrupting its cloud-borne flight. The saddle supports an upright branch of the sacred sakaki tree, entwined with wisteria blossoms and hanging ornaments, which in turn supports a golden disk. Within the disk, whose glow pierces the darkness of the night sky, are five figures of buddhas and bodhisattvas.

Deer were apparently regarded as sacred in prehistoric and ancient Japan. They were represented by haniwa (see cat. no. 3) as early as the fifth or sixth century, and in time they acquired a special status as messengers of the Shinto gods. It is believed that the Fujiwara clan, whose ancestors had served the court as diviners, used deer scapulae as oracle bones, suggesting that deer were accorded a special place.[1] And beginning in the Muromachi period, deer became protected animals in the Kasuga area.

According to tradition, in 768 Takemikazuchi no Kami, the god of the Kashima Shrine (northeast of modern Tokyo), flew to Mount Mikasa on the back of a white deer. Upon his arrival he was installed as god of the First Shrine at Kasuga. Later, three more deities arrived and took up residence at three other buildings, completing the main complex of the Kasuga Shrine.[2] A small number of extant paintings depict Takemikazuchi, sometimes accompanied by other deities or by attendants, on his way to Kasuga. The Deer mandala of the Kasuga Shrine (Kasuga shika mandara) most likely evolved from such images. About thirty Deer mandalas are known today.[3] Several display the deer within the Kasuga precinct, against the backdrop of Mount Mikasa, with shrine buildings in the foreground. Most of them, however, like this one, represent the deer alone, bearing the sacred tree that supports a disk or the sacred mirror.

Paintings such as these were the products of the syncretic interaction between Buddhism and Shinto. This evolution, which allowed the two religions to coexist in harmony, led in turn to honji suijaku, the belief that Shinto gods were manifestations of Buddhist deities. Thus, each god of the Kasuga Shrine was given a Buddhist identity, called honji butsu (Buddhas of the Original Land). Icons used in the service of honji suijaku gained popularity in the late thirteenth century. It has been suggested that the movement was spurred by the invasions of Japan by the combined forces of China and Korea in 1274 and again in 1281. On both occasions, prayers were offered nationwide to invoke the assistance of Shinto gods.[4] This came, miraculously, in the form of kamikaze (divine winds, or typhoons).

It would appear that standards for the production of Deer mandalas and rules regarding their worship were established by the end of the thirteenth century.[5] According to one tradition, the general composition of the mandalas was based on an apparition that appeared to one Fugenji Mōtōmichi sometime during the reign of Emperor Antoku (1180–85).[6] And they seem to have been worshiped as the principal icons of the Kasugakō, a lecture-ceremony conducted periodically at the Kasuga Shrine.

The Buddhist deities enclosed in the golden disk of the Burke mandala are Shaka (Skt: Shakyamuni), center, residing at the First Shrine; Yakushi (Bhaishajyaguru), top right, holding a medicine jar and residing at the Second Shrine; Jizō (Kshitigarbha), top left, holding a jewel and a staff, residing at the Third Shrine; Monju (Manjushri), lower right, residing at the Wakamiya (see cat. no. 32), and Kannon (Avalokiteshvara), bottom left, residing at the Fourth Shrine. Below the disk and the sakaki branch supporting it, the deer's taut body and sharp gaze convey a sense of the mystical power with which the animal is endowed. The tense pose, with forelegs spread wide, suggests a sudden arresting of movement. In contrast, the cloud with trailing vapor creates an impression of flowing motion.

It is believed that most Deer mandalas were produced in the Nara region, primarily by artists attached to large, powerful Buddhist temple workshops, such as those at Kōfukuji and Tōdaiji. This particular work may be dated to the late fourteenth century. Kasuga Shrine and Deer mandalas increased in popularity during the Kamakura period, when the realistic depiction of nature became prevalent in the visual arts and there was a new desire to endow devotional images with a sense of both the real and the divine.

[Miyeko Murase 2000, Bridge of Dreams]

[1] Nagashima Fukutarō 1944, pp. 9ff.

[2] Ko shaki (Records of Old Shrines), in Kasuga 1985, pp. 3–15.

[3] Listed in Gyōtoku Shin'ichirō 1993, p. 17.

[4] Ibid., p. 8.

[5] Kasugasha shiki (Private Records of the Kasuga Shrine) by Nijō Norinaga, in Kasuga 1985.

[6] Nara National Museum 1964b, p. 24.

Deer were apparently regarded as sacred in prehistoric and ancient Japan. They were represented by haniwa (see cat. no. 3) as early as the fifth or sixth century, and in time they acquired a special status as messengers of the Shinto gods. It is believed that the Fujiwara clan, whose ancestors had served the court as diviners, used deer scapulae as oracle bones, suggesting that deer were accorded a special place.[1] And beginning in the Muromachi period, deer became protected animals in the Kasuga area.

According to tradition, in 768 Takemikazuchi no Kami, the god of the Kashima Shrine (northeast of modern Tokyo), flew to Mount Mikasa on the back of a white deer. Upon his arrival he was installed as god of the First Shrine at Kasuga. Later, three more deities arrived and took up residence at three other buildings, completing the main complex of the Kasuga Shrine.[2] A small number of extant paintings depict Takemikazuchi, sometimes accompanied by other deities or by attendants, on his way to Kasuga. The Deer mandala of the Kasuga Shrine (Kasuga shika mandara) most likely evolved from such images. About thirty Deer mandalas are known today.[3] Several display the deer within the Kasuga precinct, against the backdrop of Mount Mikasa, with shrine buildings in the foreground. Most of them, however, like this one, represent the deer alone, bearing the sacred tree that supports a disk or the sacred mirror.

Paintings such as these were the products of the syncretic interaction between Buddhism and Shinto. This evolution, which allowed the two religions to coexist in harmony, led in turn to honji suijaku, the belief that Shinto gods were manifestations of Buddhist deities. Thus, each god of the Kasuga Shrine was given a Buddhist identity, called honji butsu (Buddhas of the Original Land). Icons used in the service of honji suijaku gained popularity in the late thirteenth century. It has been suggested that the movement was spurred by the invasions of Japan by the combined forces of China and Korea in 1274 and again in 1281. On both occasions, prayers were offered nationwide to invoke the assistance of Shinto gods.[4] This came, miraculously, in the form of kamikaze (divine winds, or typhoons).

It would appear that standards for the production of Deer mandalas and rules regarding their worship were established by the end of the thirteenth century.[5] According to one tradition, the general composition of the mandalas was based on an apparition that appeared to one Fugenji Mōtōmichi sometime during the reign of Emperor Antoku (1180–85).[6] And they seem to have been worshiped as the principal icons of the Kasugakō, a lecture-ceremony conducted periodically at the Kasuga Shrine.

The Buddhist deities enclosed in the golden disk of the Burke mandala are Shaka (Skt: Shakyamuni), center, residing at the First Shrine; Yakushi (Bhaishajyaguru), top right, holding a medicine jar and residing at the Second Shrine; Jizō (Kshitigarbha), top left, holding a jewel and a staff, residing at the Third Shrine; Monju (Manjushri), lower right, residing at the Wakamiya (see cat. no. 32), and Kannon (Avalokiteshvara), bottom left, residing at the Fourth Shrine. Below the disk and the sakaki branch supporting it, the deer's taut body and sharp gaze convey a sense of the mystical power with which the animal is endowed. The tense pose, with forelegs spread wide, suggests a sudden arresting of movement. In contrast, the cloud with trailing vapor creates an impression of flowing motion.

It is believed that most Deer mandalas were produced in the Nara region, primarily by artists attached to large, powerful Buddhist temple workshops, such as those at Kōfukuji and Tōdaiji. This particular work may be dated to the late fourteenth century. Kasuga Shrine and Deer mandalas increased in popularity during the Kamakura period, when the realistic depiction of nature became prevalent in the visual arts and there was a new desire to endow devotional images with a sense of both the real and the divine.

[Miyeko Murase 2000, Bridge of Dreams]

[1] Nagashima Fukutarō 1944, pp. 9ff.

[2] Ko shaki (Records of Old Shrines), in Kasuga 1985, pp. 3–15.

[3] Listed in Gyōtoku Shin'ichirō 1993, p. 17.

[4] Ibid., p. 8.

[5] Kasugasha shiki (Private Records of the Kasuga Shrine) by Nijō Norinaga, in Kasuga 1985.

[6] Nara National Museum 1964b, p. 24.

Publicité

Publicité

Commentaires

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F79%2F08%2F119589%2F129532429_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F51%2F46%2F119589%2F126931269_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F87%2F49%2F119589%2F126931074_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F95%2F119589%2F126875799_o.jpg)