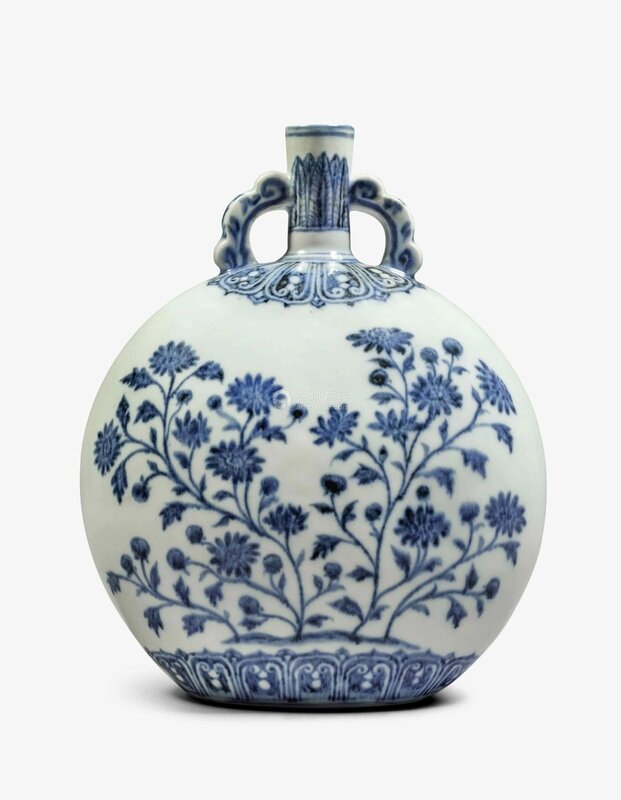

An exceptionally rare and important blue and white moon flask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424)

Lot 4. An exceptionally rare and important blue and white moon flask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424). Estimation 2,200,000 — 3,000,000 USD. Unsold. Photo: Sotheby's.

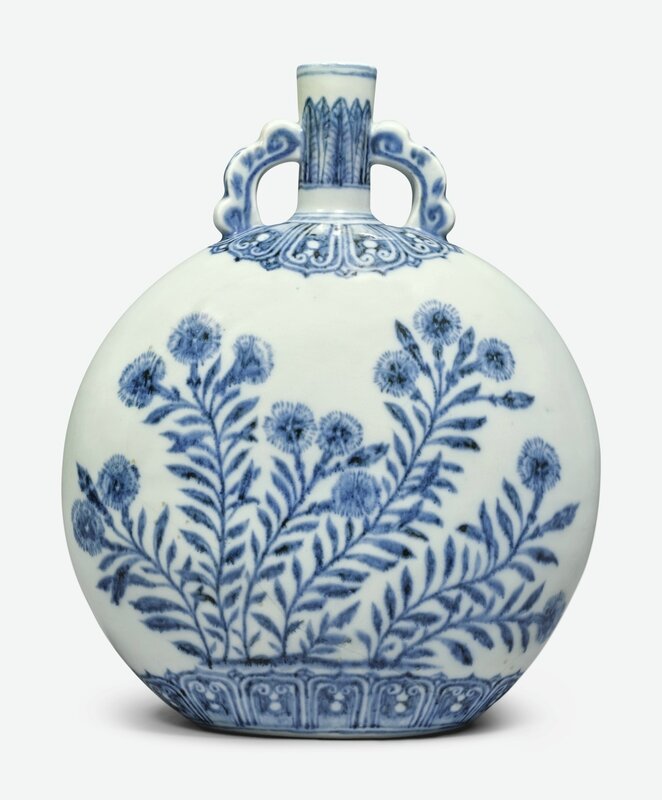

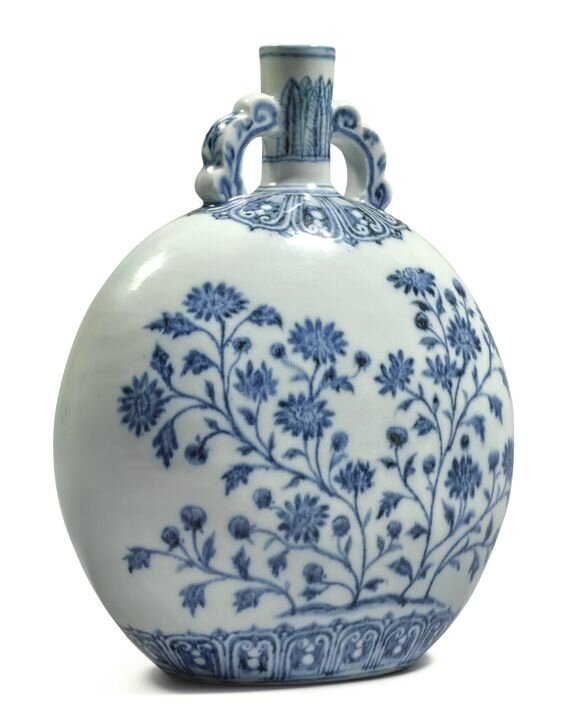

elegantly potted, the full-bodied swelling flask with a flattened globular body of elongated section, surmounted by a slender cylindrical neck flanked by two scroll handles and resting on a slightly concave flat base, exquisitely painted on either side of the body with masterful arrangements of blossoming flowers, with carnations on one side and asters on the other, all between lotus-lappet borders encircling the foot and shoulder, the neck with a band of over-lapping lappets, the handles with small florets and a scroll outlining the sides, the unglazed base with a drilled owner's mark. Height 11 3/8 in., 28.8 cm

Provenance: An Austrian Private Collection, prior to 1940 (by repute).

An English Private Collection, acquired in the 1950s.

Sotheby's London, 9th November 2005, lot 291.

Exhibition: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2012 - 2015 (on loan).

China without Dragons, The Oriental Ceramic Society at Sotheby’s, London, 2016, cat. no. 103.

Bibliography: Regina Krahl, 'China without Dragons. An Exhibition of the Oriental Ceramic Society', Orientations, vol. 47, no. 8, November/December 2016, p. 97, fig. 9.

Carnations Swaying in the Wind: An Iconic Yongle Moon Flask

Regina Krahl

Yongle (r. 1403-1424) imperial porcelains are admired for their intrinsic beauty and physical quality, but this moon flask stands out: it is an iconic piece. Enticingly shaped and alluringly painted with one of the most enchanting flower designs, it is as pleasing to hold as it is to behold. Its fine workmanship and its harmony of form and decoration reflect the fundamental strengths of China’s porcelain production in this period. Its irresistible charm elevates it beyond the universally high standard of the Yongle imperial kilns. With only one companion piece of the same design, preserved in the Ottoman royal collection, this large moon flask is one of the most remarkable upright vessels of early Ming (1368-1644) imperial porcelain still in private hands.

It was in the Yongle reign that the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province were brought under strict imperial control. The Yongle Emperor clearly recognized the diplomatic potential of a product that was highly sought-after throughout Asia and of which China held a monopoly. Fine porcelains were of course also sent to the court and are remaining in the palace collections of Beijing and Taipei; yet some of the best pieces produced during that period were officially shipped abroad or granted to foreign embassies arriving in China, as prestigious gifts.

In the Yongle reign, the imperial court controlled not only the design and production of the wares from the imperial kilns, but also their distribution. Yongle porcelain was not available through the usual trading channels, which had brought Yuan (1279-1368) porcelains to the lands of the Near and Middle East and to East Africa. In excavations in the Middle East, where successive strata testify of the existence of continuous trade in Chinese ceramics, Yongle wares are notably absent. They were made and distributed under strict court supervision, with seconds being destroyed and buried so that they could not be copied, which clearly increased their value and their demand. Middle Eastern copies of Yongle designs, which are not uncommon, generally date from a least a century later, since models were not easily available to imitate.

The distribution of Yongle porcelains in the Yongle reign was probably largely due to the ambitious official maritime expeditions of the eunuch, Admiral Zheng He, who during the Yongle and early Xuande (1426-1435) periods undertook seven gigantic voyages westward, touching down at all important ports in Southeast and South Asia, along the Persian Gulf, on the Arabian Peninsula, along the Red Sea and almost halfway down the east coast of Africa. Besides silks, porcelains were the preferred Chinese goods abroad, and were exchanged against rare animals, medicinal and food plants, pearls, precious stones, ivory, tortoise shell, rhinoceros horn, incense and other luxury goods. Porcelains such as this moon flask, which is quintessentially Chinese in style and would immediately have been recognized as such in the Middle East, were so highly valued probably exactly because of their perceived exotic flair.

In China, the somewhat elliptical sides of these moon flasks were either recognized – or perhaps specially fashioned – to echo the shape of Chinese fans that traditionally served Chinese painters as canvases for nature studies. It is therefore not surprising that such subjects came to mind to Jingdezhen’s porcelain painters, when they approached these flasks.

The flowers depicted on the front and reverse of this flask, carnations and asters, are otherwise hardly seen on Chinese porcelain, and the romantic manner in which they are here represented is extremely rare among plant designs on Chinese porcelain, which generally are stylized into patterns, with flowers depicted as detached sprays floating in mid-air or as continuous scrolls. The painterly aspect of the present flower motifs is further emphasized by the indication of uneven ground from which the flowers grow, evoking real plants in a garden setting. In their naturalistic depiction, the two scenes are reminiscent of the treatment of plants in Chinese paintings. Nearly circular fan paintings with such studies of single flowering plants are well known from the Song dynasty (960-1279) and continued to be popular into the Ming (1368-1644). Compare, for example, two anonymous Song fan paintings, one depicting a branch of double-flowering peach, the other chrysanthemums with a butterfly hovering above, both preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing, and illustrated in Zhonghua wuqian nian wenwu jikan. Song hua bian/“Five Thousand Years of Chinese Art” Series. Sung Painting, part IV, Taipei, 1986, pls 69 and 90 (figs 1 and 2).

fig 1. Anonymous, Peach flower, Song dynasty, ink and color on silk, album leaf © The Palace Museum, Beijing

fig 2. Anonymous, Chrysanthemum and butterfly, Song dynasty, ink and color on silk, album leaf © The Palace Museum, Beijing

Only one companion piece exists of the same shape, size and design, the celebrated moon flask fitted with an Ottoman silver-gilt rim mount and screw cap, preserved in the Ottoman royal collection in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. That flask has been illustrated over and over and has repeatedly featured on book covers and dust jackets. It was chosen, for example, for the dust jacket of the catalogue raisonné of the Museum’s Chinese ceramics, which are rich in fine early Ming blue-and-white wares, see Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, ed. John Ayers, London, 1986, vol. 2, where it is also illustrated in color, p. 423 and discussed as cat. no. 613, and where further publications are listed. It graces the cover of the exhibition catalogue Ceramic Masterpieces of the Orient from the Topkapi Palace, Turkey, Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo, 1990, with both sides illustrated again, cat. no. 18; as well as the dust jacket of Nakazawa Fujio and Hasegawa Shoko, Chūgoku no tōji/Chinese Ceramics, vol. 8, Gen Min no seika/Blue-and-White in Yuan and Ming Dynasties, Tokyo, 1995, with the opposite side illustrated as col. pl. 43; both sides are also illustrated as reference figures in the exhibition catalogue Jingdezhen Zhushan chutu Yongle guanyao ciqi [Yongle Imperial porcelain excavated at Zhushan, Jingdezhen], Capital Museum, Beijing, 2007, p. 15, fig. 3, by Ma Wenkuan, who characterizes its decoration as being “of pure and fresh beauty and excellence, great in elegance and serenity”.

The designs on both flasks are clearly based on the same draft, and vary only slightly in detail. While the carnations are similarly, perhaps somewhat more freely, rendered on the present piece than on the Topkapi Saray flask, the layout of the asters is here more compact, with some small leaves on the outer edges omitted to create a more concise composition. The Topkapi Saray flask bears two drilled owners’ marks on the base, one consisting of three dots very similar to the mark on the present flask, the other probably representing Arabic writing, but illegible. Such marks were applied particularly in Iran to early Ming porcelains, and both flasks may have come from China directly to Iran in the Yongle period before being separated and one ending up in Turkey.

Only one other Yongle moon flask is similarly decorated to echo a fan painting, the famous flask in the Sir Percival David Collection in the British Museum, which depicts birds on flowering branches between curling cloud motifs; it is equally reproduced in numerous publications, for example, in Regina Krahl and Jessica Harrison-Hall, Chinese Ceramics. Highlights from the Sir Percival David Collection, London, 2009, no. 28 and p. 59 (fig. 3). A moon flask of the same design appears in a painting by Iran’s most famous painter Riza-yi ‘Abbasi (c. 1565-1635), court painter under the Safavid Shah ‘Abbas I (r. 1587-1629), who donated the Safavid royal collection of Chinese porcelains to the Ardabil Shrine.

fig. 3. A blue and white ‘bird and flower’ moon flask, Ming dynasty, early 15th century. Copyright the Sir Percival David Collection/© The Trustees of the British Museum

Only two further flasks, one also in the Topkapi Saray Museum, the other in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, are comparable in size and status, both showing the same supporting designs of upright petals on the neck and petal panels at the shoulder and foot, but are decorated in between with foreign musicians and dancers; see Krahl, op.cit., cat. no. 612; and Minji meihin zuroku, [Illustrated catalogue of important Ming porcelains], vol. 1, Tokyo, 1977, pl. 14.

This double-handled, oval-sectioned shape is probably derived from pottery vessels that can ultimately be traced to the 18thDynasty of Egypt (c. 1543–1292 BC), but continued to be popular there for centuries. Examples from 6th/7th century Roman Egypt were known as St. Menas flasks since, filled with oils or holy water, they served Christian pilgrims to the tomb of St. Menas near Alexandria as souvenirs, which gave rise to the term ‘pilgrims’ flasks’. It was around that time that such flasks (bianhu) arrived in China, probably with Sogdian merchants, and were copied in lead-glazed earthenware.

By the time the imperial potters at Jingdezhen became interested in this shape, it retained only a basic relationship to the original form. The sophisticated, faintly elliptical, circular outline of this flask and its bulging sides, which make the softly rounded shape so endearing, are superbly counterbalanced by the slender cylindrical neck and fanciful curled handles, which add a light and elegant touch. It is a shape that clearly represented a challenge for potters used to throwing vessels on the potter’s wheel. Different ways of forming it were experimented with in the Yongle period. A similar piece, of slightly smaller size than the present flask, made from two vertically joined halves – which might seem the obvious way to fashion it – was abandoned at the kilns and has been recovered from the waste heaps of the kiln sites; see Jingdezhen chutu Ming chu guanyao ciqi/Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain Excavated at Jingdezhen, Chang Foundation, Taipei, 1996, cat. no. 62. Instead, a different method of joining, which can be seen on the present flask, of two halves aligned horizontally, became prevalent and was retained throughout the Ming dynasty.

A number of smaller (around 25 cm) Yongle moon flasks of this form are preserved, painted with fruit or flower scrolls encircling the whole body, which no longer evoke fan paintings. Even such examples have very rarely been offered at auction and hardly remain in private hands. Two flasks decorated with a flowering camellia scroll are in the Palace Museum, Beijing, published in Geng Baochang, ed., Gugong Bowuyuan cang Ming chu qinghua ci [Early Ming blue-and-white porcelain in the Palace Museum], Beijing, 2002, vol. 1, pls 87 and 88; one in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, is illustrated in Minji meihin zuroku, op.cit., pl. 16; one in the Shanghai Museum, in Lu Minghua, Shanghai Bowuguan zangpin yanjiu daxi/Studies of the Shanghai Museum Collections : A Series of Monographs. Mingdai guanyao ciqi [Ming imperial porcelain], Shanghai, 2007, pl. 3-9, and on the books’ dust jacket; and one in the Musée Guimet, Paris, in Fujioka Ryoichi and Hasebe Gakuji, eds, Sekai tōji zenshū/Ceramic Art of the World, vol. 14: Min/Ming Dynasty, Tokyo, 1976, col. pl. 13.

A smaller moon flask with formal lotus scrolls from the Qing emperors’ summer resort Bishu Shanzhuang at Chengde in Hebei province is illustrated in Zhongguo taoci quanji [Complete series on Chinese ceramics], vol. 12, Shanghai, 2000, pl. 17. A similar flask with a peony scroll, with reduced neck, engraved with the name of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (r.1658-1707) and a date equivalent to 1659-60, is published in Jessica Harrison-Hall, Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, pl. 4:17, where the possibility of a slightly later, Xuande (1426-1435), date for this design is evoked; another flask of this pattern is illustrated in John Ayers, Chinese Ceramics. The Koger Collection, London, 1985, pl. 51 and Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, vol. 4, London, 1994-2010, no. 1635, and it was later sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 9th October 2012, lot 37.

Of similar Yongle moon flasks with scrolling lychee branches around the body one example is also in the British Museum from the Oppenheim collection, ibid., pl. 3:20; one in the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, from the collections of Alfred Clark and Ataka Eiichi, was included in the Museum’s exhibition Imperial Porcelain: Recent Discoveries of Jingdezhen Ware, Osaka, 1995, cat. no. 218; and one in the Matsuoka Museum of Art, Tokyo, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 18th May 1982, lot 144, was included in the Museum’s exhibition Tōyō tōji meihin zuroku [Illustrated catalogue of masterpieces of Oriental ceramics], Tokyo, 1991, cat. no. 70; and is illustrated in Sotheby’s: Thirty Years in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2003, pl. 208; a fourth was sold in our London rooms, 5th July 1977, lot 201.

Sotheby's. Ming: The Intervention of Imperial Taste, New York, 14 mars 2017, 10:00 AM

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_2a8420_437713933-1652609748842371-16764302136.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_83ee65_2024-nyr-22642-0954-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_15808c_2024-nyr-22642-0953-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_e54295_2024-nyr-22642-0952-000-a-rare-blue-an.jpg)