The Met receives monumental 10th-century Chinese painting 'Riverbank' from Oscar L. Tang

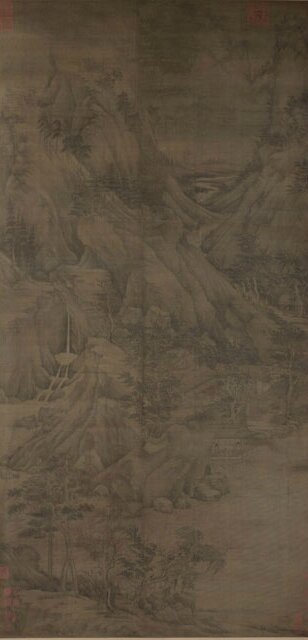

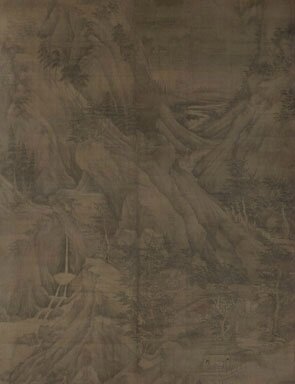

Attributed to Dong Yuan (Chinese, active 930s–960s), Riverbank. Image: 86 3/4 x 43 in. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk. Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Gift of Oscar L. Tang Family, in memory of Douglas Dillon, 2016.

NEW YORK, NY.- Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, announced today that Oscar L. Tang has donated Riverbank, one of the most important Chinese landscape paintings in existence, to the Museum.

In making the announcement, Mr. Campbell said: "For more than 25 years, Oscar Tang and his family have been extraordinarily generous supporters of The Met's efforts to build a major collection and exhibition program of Chinese art. In addition to earlier gifts of 20 important paintings that range in date from the 11th to the 18th century, Oscar has supported several major projects, including the creation of the Frances Young Tang Gallery, the Wen C. Fong Study-Storeroom, and an endowment for a junior conservator of Chinese painting. Now, with this gift of Riverbank, he has added a uniquely important treasure to The Met's holdings and, in the process, further enhanced the Museum's stature as one of the preeminent collections of Chinese painting in the world."

Mr. Tang, who is a Trustee Emeritus of the Museum and Chairman of the Department of Asian Art's Visiting Committee, said: "For a long time, my intention has been to donate Riverbank to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. I am making this gift now as an affirmation of my belief that The Met is an ideal platform on which to showcase the richness of the art and history of my family's heritage, and to care for what in China would be considered a 'national treasure.'"

A rare survivor from the formative days of Chinese landscape painting, Riverbank offers a window onto the critically important 10th century, when images of nature rose to prominence, replacing pictures of the human figure as the dominant form of pictorial expression. The handful of paintings that survive from this period, along with textual evidence, indicate that it was a time of epochal transformation, when the painting of landscapes made a quantum leap in scale, sophistication, and ambition. Riverbank is one of the key pieces of evidence of this revolution.

Maxwell K. Hearn—Douglas Dillon Chairman of the Department of Asian Art and author of Along the Riverbank, the 1999 catalogue on Riverbank and 11 other works from Mr. Tang's collection—observed: "Oscar Tang's gift of Riverbank is the capstone of a four-decade-long effort begun in 1973 by the Department of Asian Art's Chairman Emeritus Wen C. Fong to build up The Met's holdings of Chinese painting. This donation, together with earlier gifts and purchases made possible by Mr. Tang, Douglas Dillon, John M. Crawford Jr., and many others, gives The Met the ability to narrate one of the great stories in Chinese art: the rise of a grand tradition of monumental landscape painting in the 10th century and its transformation into a self-expressive art form from the 11th to the 14th century."

Monumental in scale, and the tallest of all existing early Chinese landscape paintings, this imposing mountainscape was painted in ink with light colors on silk now darkened with age. It shows in the foreground a pavilion structure at a river's edge; a scholar wearing a cap and gown, accompanied by his wife and child and a boy servant, sits in a yoke-back chair by the railing, looking out at the gathering storm. Beyond the pavilion, great pines and deciduous trees along the riverbank bend ominously in the wind, and the water rises in choppy, netlike waves. Behind the pavilion, a steep foothill ascends leftward in a series of thrusting boulders, and to the left a waterfall rushes down to the river. A winding pathway connects the foreground with a mist-veiled river valley in the deep distance, where wild geese fly by in formation, and hills beyond the river rise and twist in tortuous formations. Scurrying along the narrow path, six travelers, one of them wearing a thatch cloak and hat, hurry back to the mountain villa. A boy on a water buffalo at water's edge heads toward a courtyard compound, surrounded by a bamboo grove and a brushwood and bamboo fence. Inside the compound, a woman prepares a meal while another woman carries a tray of food along the covered porch. With the family residence visible behind the courtyard, the master and his family assemble in the pavilion on the riverbank—a perfect metaphor for a safe haven in a threatening world.

During the period of disunion that followed the fall of the Tang dynasty in 907 and the establishment of the Song dynasty in 960, a number of masters rose to prominence by creating images that captured something of the power and grandeur of nature. These masters tended to eschew the bright, decorative palette of Tang landscapes in favor of monochrome ink, using subtly graded washes to capture the visual effect of atmospheric mists. They also painted at large scale, enveloping the viewer's gaze within a transporting vision of nature's majesty. This tradition, which coalesced in the 10th and 11th centuries, has come to be known as Monumental Landscape.

Riverbank is one of the most important sources we have for this tradition's foundation. Its landscape forms are described through subtly applied washes of diffuse ink that accumulate into alternating bands of light and dark. The softly rubbed-on texturing and absence of distinct contour lines reflects the transformation of an earlier tradition, which is preserved in paintings of the Tang dynasty. By the middle of the Northern Song dynasty in the 11th century, signature line work had become the landscape painter's key tool in describing landscape forms and textures, replacing the softer washes of Tang. Riverbank falls in between these two traditions, placing it squarely in the momentously important 10th century.

Riverbank was the subject of controversy when it was purchased from C. C. Wang in 1997. One prominent scholar, James Cahill (1926–2014) of the University of California, Berkeley, argued that the painting was not a work of the 10th century but a forgery by the 20th-century artist Zhang Daqian (1899–1983). Out of deference to Professor Cahill's stature and firm in the belief that the painting could withstand the scrutiny of the field, The Met's experts convened a symposium to address the painting's authenticity, inviting leading scholars from around the world to weigh in. The proceedings were published as Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Painting. Since that time, Professor Cahill's minority opinion has grown increasingly marginal, and the scholarly consensus that Riverbank is indeed a masterpiece of early Chinese landscape painting has grown stronger. It was exhibited in Taipei at the National Palace Museum in 2006 alongside that museum's 11th-century masterworks by Fan Kuan and Guo Xi, and at the Shanghai Museum in 2012. That these museums, among the most respected custodians and interpreters of Chinese painting in the field, share The Met's belief in Riverbank's authenticity speaks to the solidity of The Met's dating and its acceptance among Chinese painting scholars.

The painting bears a signature of Dong Yuan (active 930s–960s), one of the leading landscape painters active at the court of the Southern Tang kingdom (937–975). Though three other early attributions to Dong Yuan survive, there is no scholarly consensus on which, if any, of these works represents the real Dong Yuan, and there is significant stylistic range even within this small corpus. Given such a limited and murky sample, it is impossible to establish the kind of certainty necessary to support a firm attribution, let alone an idea of a chronology within Dong Yuan's oeuvre. For this reason, the Museum does not claim Riverbank to be a firmly identified work from the hand of the master, preferring instead to present it as one of a constellation of plausible attributions. The painting's importance rests not chiefly in its relationship to Dong Yuan, but in its majesty and completeness as a monument of early landscape painting.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)