Groundbreaking exhibition of Memento Mori from the Renaissance opens at Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Albrecht Dürer, German," St. Jerome in his Study," 1514, engraving. Bequest of David P. Becker, Class of 1970. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

BRUNSWICK, ME.- The Bowdoin College Museum of Art opened a groundbreaking exhibition on the visual culture of mortality and morality in early Renaissance Europe. On view from June 24 to November 26, 2017, The Ivory Mirror: The Art of Mortality in Renaissance Europe reveals how, in an increasingly complex and uncertain world, Renaissance artists sought to address the critical human concern of acknowledging death while striving to create a personal legacy that might outlast it. Curated by Stephen Perkinson, Peter M. Small Associate Professor of Art History at Bowdoin College, The Ivory Mirror brings together exceptional examples of memento mori, a genre of artistic and literary imagery that emerged in the early Renaissance to remind viewers of their inevitable death, to question how art historians have conventionally interpreted these objects and to propose new ways of considering their significance. In conjunction with the exhibition, a dynamic series of public programs throughout the summer and fall, ranging from film screenings to gallery talks to interdisciplinary programs with health care experts and scholars, will provide illuminating perspectives on death and the choices we make in life. An international symposium will convene distinguished scholars to address the intersection between a fascination with death, luxury, and new techniques of representation in Renaissance Europe.

The Ivory Mirror brings together nearly seventy exquisite artworks, many of which have never been seen before in North America, from European and American institutions—among them the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and The Huntington Library in San Marino. New scholarship across the humanities features critical new discoveries, such as the attribution of several ivories, of previously uncertain authorship, to Chicart Bailly, a prosperous ivory carver active in Paris from at least the 1490s until 1533. The precious objects included in the exhibition—from ivory prayer beads and gem-encrusted jewelry to exquisitely carved small table sculptures—draw attention in spectacular fashion to the depictions of death, dying, and decay that proliferated in popular culture between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, when mortality rates were perilously high. The appeal of objects featuring macabre imagery urging us to “remember death”— and, by implication, to consider how best to take advantage of our time on earth—reached the apex of its popularity around 1500, when artists treated the theme in innovative and compelling ways.

Lucas van Leyden, Netherlandish, "Young Man with a Skull," ca. 1519, engraving. Gift of Charles Pendexter. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

“We’re thrilled to present the unique and rare works included in The Ivory Mirror, many of which are unfamiliar to audiences outside of Europe. These extraordinary objects bring to life a culture of mortality and reveal the emergence of new conceptions of the self in the Renaissance, humanity, and the nature of achievement, pleasure, and transgression. They raise important questions about and inform new perspectives on our present fascination with such imagery, while providing a welcome opportunity to consider the new cultural, philosophical, and scientific discourses that contributed to the popularity of the memento mori at the dawn of the sixteenth century,” said Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, “The research of curator Stephen Perkinson and his collaborators sheds new light on these fascinating objects, enabling us to better understand the complex origins and associations of memento mori imagery, the larger artistic and literary context of which they were a part, the nature of the workshops that designed them, and, ultimately, how these remarkable works of art continue to evoke the tension between pleasure and responsibility in a fashion just as compelling today as five centuries ago.”

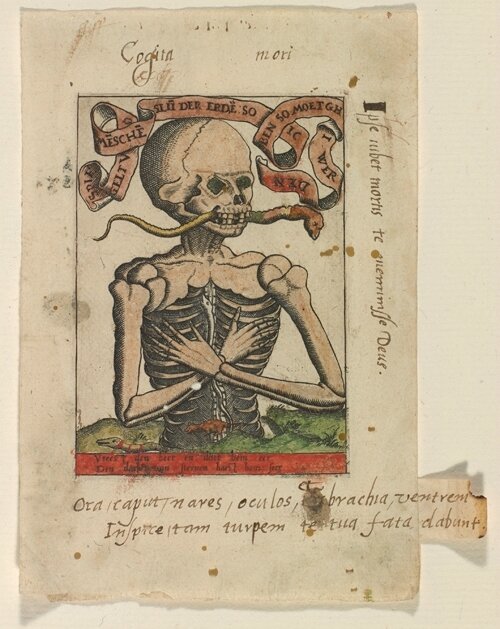

Master S (Alexander van Brugsal?), Netherlandish, "Memento Mori," ca. 1520, engraving, with contemporary hand coloring. Gift of Linda and David Roth in memory of David P. Becker and Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

An elegant installation, organized into eight thematic sections, focused on subjects such as selfhood, morality, piety, and anatomy, enables audiences to understand the broad range of inspirations for and implications of memento mori imagery. Cases provide the opportunity to see ivory prayer beads and other statuettes in the round and in the context of paintings and prints from the period by leading artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein. Magnifying glasses further permit close examination of the exceptional detail with which artists of the period wrought the ivory objects brought together for the first time in The Ivory Mirrror.

“While we recognize the Renaissance as an age of exceptional human progress and artistic achievement, macabre images proliferated in precisely this period: unsettling depictions of Death personified, of decaying bodies, of young lovers struck down in their prime. This provocative imagery runs riot in the remarkable array of artworks featured in The Ivory Mirror. For many scholars, these gruesome objects seem to be a last gasp, as it were, of a dying medieval world view, of a culture obsessed with the certainty of death, terrified by the threat of divine judgment, and incapable of enjoying earthly life,” continued curator Stephen Perkinson, “The Ivory Mirror rethinks that traditional view, seeking to understand these morbid images as intimately bound up in the period’s shifting conceptions of the self, of the place of humanity in the world, and of the nature of sin and pleasure. It demonstrates that these objects simultaneously reminded viewers not only of life’s fleeting nature but also of the need to both enjoy one’s time on earth and to live a moral and responsible life.”

Hans Holbein the Younger, "Death and the Rich Man," ca. 1526, woodcut. Bequest of David P. Becker, Class of 1970. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

The BCMA displays highlights from their own collection alongside artworks loaned from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Walters Art Museum among others. Highlights of the exhibition include:

• Several stunning memento mori ivory pendants and rosary beads on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Walters Museum of Art, and from the BCMA’s own collection; and

• Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dance of Death woodcut series, on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston;

• A boxwood sculpture from the School of Conrad Meit, Vanitas, ca. 1525, on loan from the Harvard Art Museums;

• A copy of Andreas Vesalius’s momentous anatomical compendium, On the Fabric of the Human Body of 1543, on loan from Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University;

• Illuminated manuscripts and early printed books of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries on loan from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California and the Clapp Library of Wellesley College;

• Albrecht Dürer’s engraving The Fall of Man (Adam and Eve), 1504, from the collection of the BCMA;

• Masterful decorative arts objects on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum by unknown artists, including an early seventeenth-century gold and enamel ring, an enameled, jewel-encrusted gold brooch, and a silver scent case from the early sixteenth century.

• A superb bronze figural inkwell by the Nuremberg artist Peter Vischer the Younger, on loan from the Ashmolean museum in Oxford, whose decoration evokes the carpe diem theme with an inscription urging its viewers to “reflect on life, not death.”

The fully-illustrated 240-page catalogue includes nearly 190 color images and five essays penned by scholars from institutions such as the British Museum and the J. Paul Getty Museum. The Ivory Mirror celebrates advances made in the scholarship of memento mori in visual and literary culture of the early modern era, and will provide a platform for further interdisciplinary engagement.

Johan Wierix, Flemish, "The Coat of Arms of Death," 1549-1615, engraving. Museum Purchase. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Unknown Artist, German/Netherlandish, Memento Mori Prayer Bead, 1500-1550, ivory. Gift of Linda and David Roth in memory of David P. Becker. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

“Portrait of a Surgeon,” Netherlands, 1569, oil on wood. Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

"Memento Mori Pendant", probably from a rosary, France or Belgium, 1500, ivory, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Walter E. Stait Fund, 2007

Office of the Dead, Book of Hours, beginning of the 16th century, parchment by an unknhown artist, France. The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Skull and Bones, ca. 1600, engraving by Jan Pietersz. Saenredam, Dutch, ca. 1565-1607. Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Muriel and Philip Berman Gift, acquired from the John S. Phillips bequest of 1876 to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, with funds contributed by Muriel and Philip Berman, gifts (by exchange) of Lisa Norris Elkins, Bryant W. Langston, Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, with additional funds contributed by John Howard McFadden, Jr., Thomas Skelton Harrison, and the Philip H. and A.S.W. Rosenbach Foundation, 1985

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F20%2F119589%2F127268174_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F53%2F119589%2F122128977_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F98%2F119589%2F117635941_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F67%2F43%2F119589%2F112185117_o.jpg)