Exhibition devoted to environmentally-conscious artists on view at Florence Griswold Museum

Martin Johnson Heade, Jungle Orchids and Hummingbirds, 1872. Oil On Canvas, 18 1/4 x 23 in., 46.4 x 58.4 cm; Yale University Art Gallery, Christian A. Zabriskie and Francis P. Garvan, B.A. 1897, M.A.(Hon.) 1922, Funds, 1971.80. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

OLD LYME, CONN.- The Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, is presenting a major exhibition entitled Flora/Fauna: The Naturalist Impulse in American Art, on view through September 17, 2017. Drawn extensively from the Museum’s collection, as well as many public and private lenders, the 101 works in the exhibition survey the history of environmentally-conscious artists in the United States from the dawn of the 19th century through the mid-20th century. Flora/Fauna begins with early-American artists such as the Peale family, John James Audubon and their contemporaries, then examines the naturalist impulse in works by the Hudson River School, American Pre-Raphaelites, and American Impressionist artists before featuring select 20th-century artist-naturalists such as Roger Tory Peterson, creator of widely-used bird guides. Works in the exhibition reveal how artistic production corresponded with social developments in American history, from an early concern with establishing a national identity distinct from Europe; to reflecting Americans’ shifting philosophies on evolution and the human relationship to the environment; to the growth of the conservation movement in the United States.

The Artist-Naturalist in Early America

The birth of natural history in America coincided with the founding of the country. Such artists as Mark Catesby, William Bartram, the Peale family, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon participated in the American Enlightenment by pioneering many of the country’s firsts—the first natural history publications, institutions, and environmental experiments. Scientists quickly realized that they needed the assistance of artist-naturalists to give visual form to their discoveries and disseminate that knowledge through books, botanic gardens, lectures, and museum displays.

During this age of Enlightenment, many political leaders, including Thomas Jefferson, looked to natural history to help forge the identity of the new nation. Not surprisingly, the country’s first scientific center developed in and around its first capital. Philadelphia attracted the brightest intellectual, scientific, and artistic minds that formed a network of new professionals. Works in this section by the Bartram, the Barton, and the Peale families reveal that the forging of an American natural history was often a ‘family affair’ facilitated by personal relationships. Titian Ramsay Peale’s, Monarch Butterfly [No. 16], 1817 (American Philosophical Society Library) a work from an entomological sketchbook, demonstrates how artists participated in the discovery, documentation, and collection of natural specimens. The sketch shows the monarch at different stages of life. Beneath the illustration, he wrote his scientific observation: “Went into the Chrysalis state on the 4th of Septemb—and became perfect on the 13thof the same month.”

Mark Catesby, Hooping Crane [Whooping Crane],1731, from The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, v. 1. Etching and watercolor on paper, 21 ½ x 24 ¾ in. Collection of the Museum of American Bird Art at Mass Audubon, Art Acquisition and Restoration Fund purchase through a gift by Julianne Mehegan in memory of Eloise Faison, 2012. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Titian Ramsay Peale, Monarch Butterfly [No. 16], 1817. Watercolor, 9 15/16 x 8 in., American Philosophical Society Library, Titian Ramsay Peale Sketches. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

John James Audubon and Joseph R. Mason, Black-billed Cuckoo, 1828, from The Birds of America, first edition. Engraving, etching, aquatint, and watercolor on paper, 39 x 26 in. Collection of the Museum of American Bird Art at Mass Audubon, Bequest of Anna Bemis Stearns, 1995. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Nature’s Nation: The Hudson River School

Building on the documentary and aesthetic achievements of the artist-naturalists before them, the Hudson River School painters sought to capture what was unique about the American land—its vast, untouched wilderness. The group who has become known as the Hudson River School first took up this task around the mid-nineteenth century. Based in and around New York City, they traveled to such areas as the Hudson River Valley of New York and the White Mountains of New Hampshire to experience expansive American scenery firsthand. Their resulting paintings symbolically linked the natural landscape to concepts of nationalism and environmentalism, equating the American landscape with American identity. For Hudson River School painters, pictorializing nature in the United States became a mode of social and environmental criticism that reflected scientific and ecological questions of the time, and laid the roots for the American conservation movement as well as the national park system.

Beginning with Thomas Cole’s allegorical admonitions about man’s intrusion on nature, others such as Asher B. Durand and Frederic Church evolved to value realism over metaphor, reflecting their firsthand observations of American scenery in highly detailed paintings both modest and vast—finding beauty in nature’s growth and decay. Martin Johnson Heade can be called a quintessential artist-naturalist. His inventive combination of elements of scientific illustration (in his exactness of representation), his dramatic use of still life elements (birds and flowers), and his evocative placement of them in their natural environment gave his works a power not seen before in American painting. These traits are exemplified inJungle Orchids and Hummingbirds, 1872 (Yale University Art Gallery).

Thomas Cole, Study for “A Wild Scene”, 1831. Oil on canvas, 11 x 17 in., Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company; Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

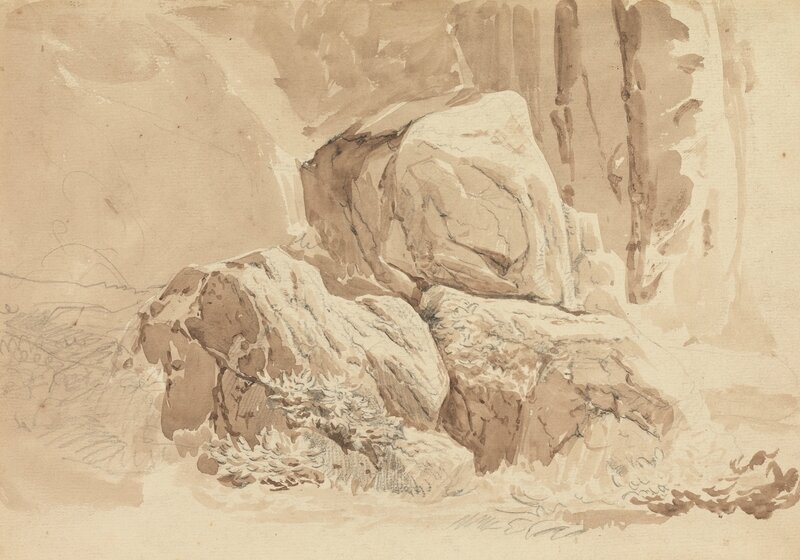

John Ruskin, The Borghese Gardens, ca. 1840. Graphite and brown wash on medium, moderately textured, cream wove paper, 6 3/8 x 8 7/8 in. Yale Center for British Art, The William K. Rose and Eugene A. Carroll Collection. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Frederic E. Church, “Autumn Landscape, Vermont”, circa 1865. Oil on wove paper laid down on board, 10-5/8 by 6-3/8 inches. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Truth to Nature: American Pre-Raphaelites & Beyond

Many of the Hudson River School artists were aware of the writings of the English artist and critic John Ruskin, one of the most significant voices in the nineteenth-century art world. Ruskin’s works spanned a variety of topics from art, architecture, and natural history (including geology, botany, and ornithology) to religion, myth, and politics. His most influential and widely read text, Modern Painters (1843), emphasized the connections between art, nature, and society, and advocated for artists to uphold a “truth to nature” in their work. Ruskin’s pledge to a morally and socially committed art led him to reject the artifice of “decorative” art in favor of an art with an authentic source, such as nature itself. His followers in the United States, the American Pre-Raphaelites, produced landscape, still life, and studies that utilized a meticulousness of detail gleaned from their close study of nature en plein air.

Prior to his involvement in the arts, Ruskin had contemplated becoming a geologist. In the nineteenth century, geology was considered a gentlemanly endeavors that many artists, including the Hudson River School and the American Pre-Raphaelites, pursued. As works in this section show, careful studies exposing evidence of the artist’s process were as highly valued as finished works. In additional to geology, botany became an enormously popular genteel hobby, and developed into a status symbol. These pursuits enabled the success of nature illustrators like Fidelia Bridges, who brought these topics to mass-marketed periodicals and, thus, into thousands of American homes. A rare portfolio of Bridges’ work in the collection of the Florence Griswold Museum has been newly conserved and will be on view for the public for the first time. Ruskin and his American followers employed a scrupulous observation of nature from life in order to convey the ‘truths’ of their subjects’ identities, as seen in Bridges’s Thistle in a Field, 1875 (Florence Griswold Museum).

Fidelia Bridges, Thistle in a Field, 1875. Oil on canvas, 14 x 10 in., Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Fidelia Bridges, “Wild Roses Among Rye”, 1874. Watercolor and gouache over pencil on paper, 13½ by 9 inches. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Willard L. Metcalf, Dogwood Blossoms, 1906. Oil on canvas, 29 x 26 in., Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company; Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Roger Tory Peterson, Satin Bowerbird, 1964. Gouache, watercolor, pencil and ink on board, 4 x 6 in. Charles T. Clark. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Willard L. Metcalf, “On the River (The Eel Trap)”, circa 1888. Oil on canvas, 21 by 25½ inches. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Impressionism & The Naturalist Impulse in Connecticut

While the “naturalist impulse” most often yielded a work of art that appeared naturalistic, or true to nature in a scientific sense, this exhibition allows for an expanded definition to include works that may be deemed “impressions” of nature. Like artists of previous generations in Europe, the American Impressionists found art colonies in the suburbs and countryside to be restorative retreats, where they could immerse themselves in nature and enjoy the camaraderie of like-minded colleagues. Around 1900, the natural landscape of Old Lyme perfectly fulfilled that need for artists. Not coincidentally, many artists who frequented art colonies, like Willard Metcalf, Childe Hassam, and Harry Hoffman, were also practicing naturalists, to varying degrees.

Childe Hassam, “The Dry Northeaster, Isles of Shoals”, 1906. Oil on canvas, 20 by 30¼ inches. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Harry L. Hoffman, “A Coral Cave”, undated. Oil on canvas, 20 by 32 inches. Gift of Carolyn Zeleny. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

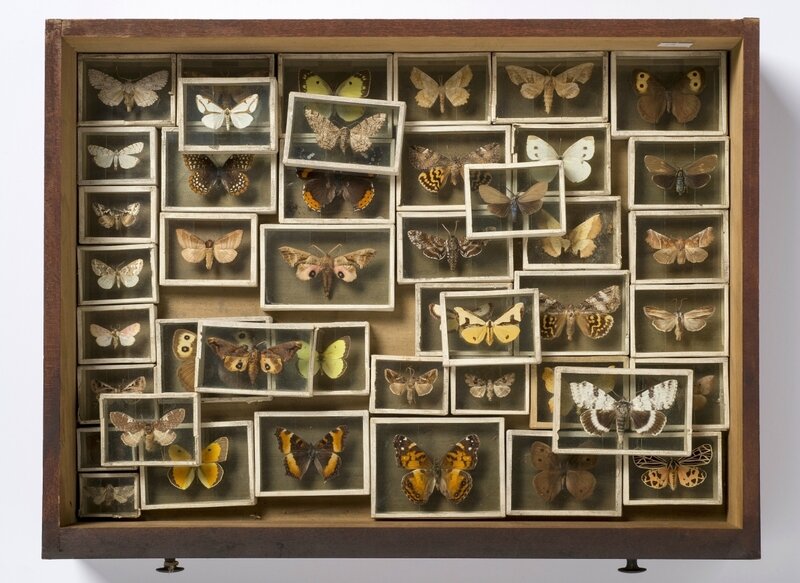

The consummate artist-naturalist of the Lyme Art Colony was Willard Metcalf. On view in Flora/Fauna is the cabinet housing his collection of specimens. One drawer contains thirty-eight glass-mounted moths, many with furry bodies and wings still displaying their original deep gold, bright yellow, or rosy pink pigments. A second drawer reveals thirty-two pink cigarette boxes containing the tiny eggs of such birds as the English Sparrow and the creamy blue eggs of a Redstart. Metcalf translated his love of the natural world to his artwork. He painted Kalmia (Florence Griswold Museum) in 1905, the first summer he stayed at Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse with the keen observations of one very much attuned to their environment. In Kalmia, Metcalf captures the smooth, blue Lieutenant River reflecting the calm sky, while fluffy white and pink blossoms and green grasses appear to breathe in the spring air.

Butterflies and moths from Willard L. Metcalf’s naturalist collection chest, circa 1885–1925. Mahogany wood drawer and specimens, 18 by 13¾ inches. Gift of Henriette A. Metcalf. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Bird eggs collected by William L. Metcalf in Giverny and Grez-sur-Loing, from Metcalf’s naturalist collection chest, circa 1885–1925. Mahogany wood drawer and specimens, 18 by 13¾ inches. Gift of Henriette A. Metcalf. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Willard L. Metcalf, “Kalmia”, 1905. Oil on canvas, 34 by 34 inches. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

The exhibition concludes with the artist-naturalist tradition that persisted into the twentieth century and still thrives today in the Connecticut River Valley. Roger Tory Peterson, who inspired the environmental movement with his activities as a naturalist, educator, and artist, purchased seventy acres of property in Old Lyme in 1954. Peterson published the first modern field guide, A Field Guide to the Birds; giving field marks of all species found in eastern North America in 1934 and developed the Peterson Identification System so that amateurs and professionals could identify species visually for close observation without hunting them. Satin Bowerbird, (Private Collection), created for reproduction in his 1964 book The World of Birds, is a simplified scene illustrating two birds interacting in their environment. These guides helped to popularize the pastime of bird watching and cultivate a national interest in wildlife.

John Martin Tracy, “Botany”, 1891. Oil on canvas, 16 by 24 inches. Bequest of Arthur J. Phelan Jr. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Charles de Wolfe Brownell, “Joshua’s Seat”, August 22, 1858. Watercolor on paper, 5¼ by 8¼ inches. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Gurdon Trumbull, “Black Bass”, 1872. Oil on canvas, 17½ by 25-1/8 inches. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Thomas Nason, “Thanatopsis”, 1947. Wood engraving on paper, 3-5/8 by 4-5/8 inches. Gift of Janet W. Eltinge in memory of Margaret Warren Nason. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

David Johnson, “West Cornwall, Connecticut”, 1875. Oil on canvas, 16¼ by 13 inches. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

John F. Kensett, “Study of a Burdock Plant”, undated. Oil on heavy paper, laid down on canvas, 9-1/16 by 15¼ inches. Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

The Butterfly Hunter’s Guide: Denton’s Patent Butterfly Tablets, Denton Brothers, Wellesley, Mass., 1902. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

Roger Tory Peterson, “Meadowlarks, Cowbirds”, circa 1990. Gouache, watercolor, pencil and ink on board with mylar overlay, 16-5/8 by 11-1/8 inches. Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F95%2F86%2F577050%2F40251569_p.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)