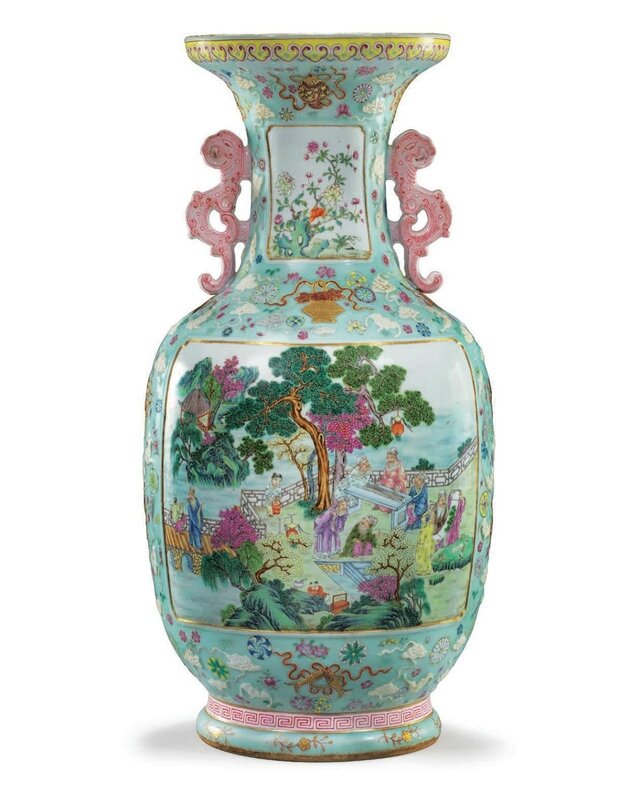

An exceptional rare and large famille rose vase, Qianlong six-character seal mark in iron red and of the period (1736-1795)

Lot 748. An exceptional rare and large famille rose vase, Qianlong six-character seal mark in iron red and of the period (1736-1795), 27 ¾ in. (70.5 cm.) high. Estimate USD 300,000 - USD 500,000. Price realised USD 372,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017

The vase is decorated on the body with two large recessed panels, one containing a scene from the 14th century novel The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi) with Liu Bei and other officials and attendants approaching a boy opening a gate while Zhuge Liang sits inside playing the qin. The panel on the reverse contains a scene of nine elderly scholars and three boy attendants on a terrace, enjoyingqin music and admiring a scroll painting. The neck is also decorated with two recessed panels, one with lotus flowers and leaves and the other with peony and rocks, and is flanked by two pink-enameled mythical beast-shaped handles. The panels are surrounded by Buddhist and Daoist emblems decorated in raised slip and blue and iron-red enamels, amid raised-slip bats and cloud scrolls, and scattered floral sprays and medallions on a pale celadon ground. The base and the interior are covered with pale turquoise enamel.

Provenance: Important private collection, France.

A magnificent Qianlong famille rose vase with historical themes

Rosemary Scott, Senior International Academic Consultant Asian Art

This rare vase combines a powerful shape and large size with very fine painting in famille rose enamels, and additional surface interest created using the impasto qualities of painting in slip. Large-scale vases with impressive decoration came to prominence in the Qianlong reign, but the majority of these have heights in the region of 40-50 cm., rather than the 70 cm. of the current vase. However, two magnificent revolving Qianlong vases in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, published in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum – 39 – Porcelains with Cloisonné Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose Decoration, Hong Kong, 1999, nos. 162 and 163, are of similarly majestic scale – 73 cm. and 86.4 cm., respectively. Interestingly, the second of these vases also includes reserved panels, and has similar raised floral roundels under the pale celadon glaze on the shoulder. Unlike the floral roundels on the current vase, those on the Beijing vase are not enamelled, but their form is comparable. Like the current vase, the two Beijing vases both have archaistic dragon handles. A further Qianlong vase of apparently similar size, also with archaistic dragon handles is in the collection of the Palace of Fontainebleau, illustrated in Le Musée chinois de l’impératrice Eugénie, Musée National du Château de Fontainebleau, 1986, figs. 16-17, p. 24, where it is shown on top of a large carved wooden display cabinet. The French vase, formerly in the collection of the Empress Eugénie (1826-1820), is of similar shape to the current vase, and has similar panels decorated in enamels – reserved against a coral and gold ground, in contrast to the celadon ground of the current vase. However, the combination of celadon glaze and fine painted enamels seems to have found particular favour at the Qianlong court. A triple-necked flask from the Qing court collection in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum – 39 – Porcelains with Cloisonné Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose Decoration, op. cit., no. 124, is a good example. The reserved panel in this instance depicts female Daoist immortals with a spotted deer in a landscape. Under the celadon glaze on this flask is a design of archaistic dragons in slip.

The lively decoration of the celadon-glazed area on the current vase with its white slip clouds, floral roundels, and the Eight Buddhist Emblems and the Eight Daoist Emblems in low relief and decorated in red, black and gold enamels, is also found on certain large Qianlong vessels without reserved panels. Several very large vases of this type dating to the late Qianlong or early Jiaqing reign and bearing European gilt mounts are in the collection of Her Majesty the Queen. A group of four gilt-mounted pear-shaped vases, two of which are decorated in this style, are illustrated by John Ayers in Chinese and Japanese Works of Art in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, vol. II, London, 2016, pp. 530-3, nos. 1313 and 1314. Archival research shows that these vases entered the Royal Collection in 1814. A very large pair of lidded bottle vases with elaborate European gilt mounts and the same celadon, slip and enamel decoration is also in the Royal Collection, illustrated ibid., pp. 534-5, nos. 1317 and 1318, and these are believed to have entered the Royal Collection in 1810. A further six similar mounted vases are illustrated ibid., pp. 536-7, nos. 1319-1324. These seem to have entered the Royal Collection either in 1818 or in 1823, and can be seen in Augustus Pugin’s 1823-4 watercolour of the Salon at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton. Two further similar vases mounted in Europe as ewers probably entered the Royal Collection in 1810, and are certainly illustrated in Pugin’s watercolour of the Banqueting Room Gallery at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, dated 1823 (see ibid., pp. 538-9, nos. 1325 and 1326).

This style of decoration applied to very large vases continued into the Jiaqing reign, although sometimes with additional enamels applied to the white clouds, as can be seen on the four massive vases, with European mounts dated c. 1815, from the collection of the Dukes of Buccleuch, which were sold by Christie’s London on 7 July, 2011, for US$ 12.8 million, setting a world auction record for ormolu-mounted porcelain.

The reserved panels on the current vase are particularly well-painted in famille rose enamels. The panels on either side of the neck are painted with lotus and peony, respectively. Assuming that this vase was originally one of a pair, the other vase would almost certainly have been decorated with the other two flowers of the four seasons – plum blossom and chrysanthemum. The two major reserved panels on either side of the body appear to depict scenes from historical literature. Significantly, although they derive from different stories, the protagonists depicted on both panels are associated with the same historical period – the end of the Han dynasty and the period of political turmoil that followed.

One panel depicts a scene from the 14th century novel The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi 三國演義) attributed to Luo Guanzhong (羅貫中, c. 1330-1400). This novel, which is regarded as one of the four great classical novels of Chinese literature, is a mixture of history, legend and mythology, which purports to chronicle events from AD 169 to 280, which was a particularly turbulent era in China’s history, encompassing the end of the Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. The first printed edition of this tale dates to 1522, although it bears a possibly spuriously dated preface of 1494. Numerous editions of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms were printed between 1522 and 1690, and it provided inspiration for the decoration of a number of finely painted porcelains. The stories in its 120 chapters are concerned with the complex interactions of three major groups who vie for power. Several of the chapters are particularly well-known and scenes from them often appear as illustrations in the various editions of the work. One of these is known as ‘Three visits to the thatched cottage’ (三顧茅廬), and describes the efforts of Liu Bei (劉備), who went on to found the Shu Han (蜀漢) state in the Three Kingdoms period (AD 220-280), to enlist the aid of the strategist Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮). Having been told that he will only succeed in recruiting Zhuge Liang if he approaches him personally, Liu Bei goes to Zhuge Liang’s house – ‘thatched cottage’, but is told by a servant that his master is not at home, and so departs leaving a message. Some days later Liu Bei returns to the cottage and this time is allowed in, but encounters not Zhuge Liang, but his brother Zhuge Jun. Some months later, Liu Bei makes a final visit to the cottage. This time he is told that Zhuge Liang is asleep. Liu Bei waits for him to wake and is rewarded for his patience, determination and good manners by Zhuge Liang agreeing to be his strategist. The scene on the vase appears to depict the first visit to Zhuge Liang’s cottage, when Liu Bei and his comrades Guan Yu (關羽) and Zhang Fei (張飛) are turned away at the door by the servant. Zhuge Liang can be seen in the interior of the cottage calmly playing the qin.

The other panel probably depicts the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (竹林七賢) enjoying music, art and animated discussion. The Seven Sages were believed to be 3rd century literary recluses, who in a period of political strictures and social injustice emerged to advocate freedom and spiritual independence. In the period of some 400 years following the fall of the Han dynasty in AD 220, which was one of political and social chaos, the Seven Sages became famous for their reactions to the world in which they found themselves – rejecting certain aspects of both Confucian and Daoist teaching. They are believed to have met in a bamboo grove in Shanyang (山陽), now in Henan province. The panel on the vase does not show them in a bamboo grove, but instead seven scholars stand or sit in a garden, attended by two servants, while an eighth scholar approaches them over a bridge, followed by his servant carrying two bundles of books.

While the Seven Sages attempted to remove themselves from politics and concentrate on leisure activities such as music and poetry, as well as philosophical discussion with those of like mind, they were also known for their prodigious consumption of wine. They became symbols of the struggle of scholars against corrupt political practices, dynastic usurpation, restrictive Confucian rules of propriety, and magical Daoism. The group was composed of Xi Kang (嵇康), Liu Ling (劉伶), Ruan Ji (阮籍), Ruan Xian (阮咸), Xiang Xiu (向秀), Wang Rong (王戎) and Shan Tao (山濤). Often considered the leader of the group, Xi Kang, (AD 223-262), also known as Ji Kang, is depicted on the vase playing the guqin (古琴), while two of the others listen with rapt attention. In addition to being a philosopher and author, Xi Kang was a skilled exponent of the guqin and composed music for that instrument. Having defended a friend against false charges, and fallen foul of Zhong Hui (鍾會), a follower of the Sima clan, Xi Kang was sentenced to death by Sima Zhao (司馬昭). Just before Xi Kang’s execution, he asked for his qin and played the masterpiece known as Guangling san(廣陵散), but left no record of the melody. The additional figure seen walking across the bridge may represent Rong Qiqi (榮啟期), who, although he lived in an earlier time, was associated with the Seven Sages from at least the 4th century.

Thus, although this rare vase makes an impressive visual impact from a distance, the complexity and detail of its decoration encourages the viewer to make a close examination of its fine enamel painting and historical themes.

Christie's. Marchant: Nine Decades in Chinese Art, 14 September 2017, New York

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F78%2F99%2F119589%2F126043260_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240313%2Fob_2a714e_431771440-1632540147515998-38392421212.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F52%2F41%2F119589%2F129167485_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F70%2F50%2F119589%2F129167314_o.jpg)