Gregg Baker Asian Art at TEFAF New York Fall 2017

A pair of six-fold paper screens, Japan, Edo period, 18th century. Ink and colour on a gold ground with take (bamboo), 170.5 x 377 cm (67.3 x 148.5 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

The right hand screen represents summer with new bamboo shoots growing amongst the tall bamboo stalks, and the left hand screen with a dusting of snow on the leaves of the bamboo and on the ground portrays winter.

Take (bamboo) represents strength, vitality and survival through adversity due to its delicate structure that bends in the wind, but never breaks. It is also known as one of the Three Friends of Winter along with the plum and the pine, each symbolizing perseverance and integrity as they survive the winter without withering. By analysing the strength, dependability and flexibility of the bamboo, the ancient Chinese scholar took these characteristics as his ultimate goals. The painting of bamboo also employs all the calligraphic brush strokes. For these reasons it has come to symbolize the gentleman scholar.

Haiku by Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875) on bamboo, written at the age of 80:

This gentleman

Grows and grows

Most auspiciously

Learn from him and

You, too, will flourish forever.

Exhibition: For a similar pair of six-fold screens attributed to Tōsa Mitsunobu held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, see Japanese Design in Art (Nihon no ishou), no.7, pl. 39

Rengetsu Ōtagaki, Kakemono (hanging scroll), Japan, Meiji period, 1868. Paper, painted in ink with two nasu (aubergines) and a poem written in calligraphy. Scroll 125 x 56.5 cm (49.3 x 22.3 in.). Painting 31 x 43.5 cm (12.3 x 17 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Signed 'Rengetsu nana jyūhachi sai (Rengetsu at seventy-eight years old)

yononaka ni

kono nari itete

omou koto

nani wa medetaki

tameshi naru ran

(To rise in the world

and achieve

what one desires

is indeed

a happy thing.)

(translation by Chiaki Ajioka, published in Black Robe White Mist pl.147, p.122)

Box inscriptions: Lid 'Ōtagaki Rengetsu, nasu gasan' (aubergine poem). Inside lid 'Shinseki, yononakani, isshu, nanajūhachisai sho, Kohitsu Ryōshin kao' (Genuine work, a poem of yononakani, written at the age of 78 and authenticated by Kohitsu Ryōshin. Monogramme). Front side 'Rengetsu nasu' (aubergines)

The painting of eggplants accompanying Rengetsu's poem brings in the spirit of humour by linking the humble vegetable with life's achievements

Rengetsu was in her lifetime a Buddhist nun, poet, calligrapher, potter and painter. Shortly after her birth in Kyoto to a samurai family with the surname Todo, she was adopted by Otagaki Mitsuhisa who worked at Chion'in, an important Jōdo (Pure Land) sect temple in Kyoto, and was given the name Nobu.

In 1798, having lost her mother and brother, she was sent to serve as a lady-in-waiting at Kameoka Castle in Tanba, where she studied poetry, calligraphy and martial arts, returning home at the age of 16 to marry a young samurai named Mochihisa. They had three children, all of whom died shortly after birth; in 1815 Mochihisa also died.

In 1819 Nobu remarried, but her second husband died in 1823. After enduring the tragic loss of two husbands and all her children, Nobu, only 33 years old, shaved her head and became a nun, at which time she adopted the name Rengetsu (Lotus Moon). She lived with her stepfather, who had also taken vows, near Chion'in. After his death in 1832 Rengetsu began to make pottery, which she then inscribed with her own waka (31-syllable classical poetry) and sold to support herself.

In 1875, having led a long and exceptional life, Rengetsu died in the simple Jinkōin tearoom in Kyoto where she had lived and worked for ten years. Jinkōin Temple is a Shingon School temple (Esoteric Buddhism); Rengestu was ordained as a nun in the Pure Land School (Jōdo Shū) but she also studied and practiced Zen and Esoteric Buddhism.

The delicate hand-built tea utensils that Rengetsu inscribed with hauntingly beautiful poems are unique combinations of poetry, calligraphy and pottery; they were as highly prized in her own lifetime as they are now. Rengetsu is also known to have inscribed her poems on utensils made by other Kyoto potters. In addition to ceramics, she also produced numerous gassaku (jointly created artworks) in the form of paintings, hanging scrolls, and calligraphic works with fellow literati artists and writers.

Exhibition: Works by Rengetsu can be found in the collections of The Tokyo National Museum and the Michigan Museum of Art. For a detailed biography of Rengestu's life and catalogue of selected works by the artist, see 'Black Robe White Mist: art of the Japanese Buddhist nun Rengestu', National Gallery of Australia, 2007.

Kanshitsu kakebotoke (hanging plate with a Buddhist image), Japan, Edo Period, 19th century. Gilt and dry lacquer, 72 x 68.5 cm (28.5 x 27 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Scene with a figure of Kannon Bosatsu seated in hanka za (half lotus position) on a lotus flower.

The hands in an-i-in mudra. The head is adorned with a decorative crown at the base of a tall top-knot. Kannon is placed before a double mandorla with armlets and a necklace adorning the body.

This particular an-i-in mudra formed by the middle fingers and thumbs is called Lower Class: Middle Life. Lower class mudras are represented by the right hand raised to shoulder level and the left hand reposing on the left knee with palm upward. The circle formed by the thumb and middle finger, a complete form, having neither beginning nor end, is that of perfection and resembles the Law of Buddha, which is perfect and eternal.

Kakebotoke (hanging Buddha) are generally circular votive plaques symbolizing mirrors and adorned with repoussé or cast images most frequently of Buddhist deities. One of the few forms of Buddhist art unique to Japan, they can be found both at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples and are presented as offerings to safeguard the compound and to ensure the prosperity of the Buddhist faith. In the Buddhist context they were hung from the eaves above the main entrance to an Image Hall, or above the frieze rail between the outer and inner sanctums of the shrine for the deity that protected the temple compound. They may also represent the actual hibutsu (hidden Buddha) which is not generally on show to the public.

Kannon Bodhisattva or Kannon Bosatsu is commonly known in English as the Goddess of Mercy represented as either male or female and depicted in many different forms and manifestations. Kannon's worship originated in India during the 1st or 2nd century and later spread to the rest of Asia. Kannon is one of Asia's most beloved deities and her worship remains non-denominational and widespread.

Kannon is a Bodhisattva and an active emanation of Amida Buddha, one who personifies compassion and achieves enlightenment but postpones Buddhahood until all can be saved. Her name first appears in the Lotus Sutra and means 'One who Observes the Sounds of the World'. She can be worshipped independently as a saviour in almost all Buddhist sects including Esoteric Buddhism sects such as Zen, Nichiren, Tendai and Pure land Buddhism devoted to Amida.

Literature: For examples of kakebotoke see Object as Insight, Japanese Buddhist Art and Ritual, Katonah Museum of Art, pp. 46-47, pl. 9-10.

Sōu Chūhō (1760-1838), Kakemono (hanging scroll), Japan, Edo period, 19th century. Paper, painted in ink with the character ichi (one). Scroll 118 x 59 cm (46.5 x 23.3 in.). Painting 27 x 50 cm (10.8 x 19.8 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Signed 'Zen Daitoku Shōgetsu rō-nō' (Former abbot of Daitoku-ji)

Seals, right 'Kochū Jitsugetsu Nagashi' (lit. in the pot, sun and moon shine eternally), left 'Chūhō'

Label on Awasebako (fitted box) 'Zen Daikokuji Shōgetsu Sho Ichi' (An Ichi painted by former abbot at Daitoku-ji Temple)

Slip of paper enclosed with a biography of the artist in Japanese and another one inscribed 'Shōgetsu, Daitokuji yonhyakujyuhachi-dai, Chūhō-sōu, Tenpō kyunen botsu yotosi Nanajyukyu' (Shōgetsu Chūhō-sōu the 418th Abbot of Daitoku-ji at 79 years old, 1838.

Chūhō Sōu. Gō (art names): Rakuyōjin, Hasui-kanjin, Shōgetsu-rōjin, Shōgetsu-sō. He was born in Kyoto and studied Zen Buddhism under Sokudō Sōki, the 406th Abbot of Daitoku-ji, the main temple of the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism in Kyoto. In 1807 Chūhō became the 418th Abbot of Daitoku-ji. After his abbotship he resided at Tokai-ji and he retired at the Shōgetsu-ken (The Studio of Pine and Moon) of the Hōshun-in a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji. In 1936 he was granted the art name Daikō Shinjyō Zenshi by Emperor Ninkō (1800-1846). Chūhō excelled in poetry, calligraphy, pottery and tea ceremony utensils.

*The Kochū Jitsugetsu Nagashi (lit. in the pot, sun and moon shine eternally) is a Zen dictum referring to an episode in the biography of Fei Changfan as recorded in vol. 82 Biographies of Alchemists of the Chinese court document Hou Hanshu (History of the Later Han) which covers the history of the Han dynasty from 6 to 189 AD.

The Daoist immortal magician Hu Gong practiced medicine in a marketplace who hung a pot before his stand from which he produced cures for any malady. Fei Changfan, the market superintendent, noticed that Hu Gong would jump into the pot every night at the close of business. No one else had noticed this unusual behaviour and one day Fei Changfan decided to visit the old man's stall, bowed to him and made an offering of food and drink. The old man saw that Changfan had realised his divine existence and invited him into the pot. Inside there were halls of jade filled with delicious liquors and meat delicacies. After spending an extraordinary few days in this parallel world, the old man swore Changfan to secrecy and they then returned to the market. However to Changfan's surprise, not only a few days had passed but in fact nearly a decade. This is a clear symbolism of the relevance of time during meditation and how little significance time holds in the realm of enlightenment.

The world inside the pot was beyond time and space, representing an absolute world within our mind. The teaching is that the sun and moon shine within all of us, and by practicing zazen (seated meditation) we can realize the source of this true 'Big Mind' and our own absolute power.

Six-fold paper screen, Hasegawa School, Japan, Edo period, 17th century. Painted in ink and colour on a gold ground, 170 x 373.5 cm (67 x 147.3 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Scene with a take (bamboo) grove on a knoll beside a river amongst clouds. Some of the clouds and the bamboo are rendered in moriage (raised design) and varying shades of gold have been used to achieve a sense of depth.

Take (bamboo) in Taoism and to a lesser extent in Buddhism symbolises the notion of emptiness, due to its tube-like structure. Just as the tao (the ineffable 'way' of Taoism) arises from nothing and returns to emptiness, the bamboo is empty at its core. In East Asian philosophy such emptiness is perceived in a positive rather than a negative light. It is also a symbol of purification.

Bamboo also represents strength, vitality and survival through adversity due to its evergreen nature and delicate structure which bends in the wind, but never breaks. It is also one of the Three Friends of Winter along with the plum and the pine, each symbolizing perseverance and integrity as they survive the winter without withering. Ancient Chinese scholars admired the strength, dependability and flexibility of bamboo and aspired to these characteristics. The practice of painting bamboo also employs the full range of calligraphic brushstrokes and is therefore considered to symbolise the gentleman scholar.

Haiku by Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875) on bamboo:

"Kono kimi wa

medetakifushiwo kasanetsutsu

sue nodainagaki

tameshinarikeri"

Translation:

"This gentleman

Grows and grows

Most auspiciously

Learn from him and

You, too, will flourish forever"

The Hasegawa School was founded by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539-1610) in the late 16th century. Despite being small, consisting mostly of Tōhaku, his sons and sons-in-law it is known today as one of the most influential artistic groups of the period. Its members conserved Tōhaku's quiet and reserved aesthetic, which many attribute to the influence of Sesshū Tōyō (1420-1506) as well as his contemporary and friend, Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591).

Provenance: Previously in the collection of Herbert Givenchy

Literature: For a set of four fusuma from the 17th century depicting bamboo in a similar manner from the Hasegawa School in the collection of Hojo, Zenrin-ji, Kyoto see The Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art, Vol. 14, 1977, p. 107, pl. 92.

Tomatsu Onaga (Himi City, Toyama Prefecture, 1932), Katsu (Living), Japan, Shōwa period, 20th century. Lacquer panel, 199.5 x 155 cm (78 .8 x 61.3 in.). Signed 'Tamotsu'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

A framed panel with a school of various fish including flounders and a mackerel pike within an underwater checker board design rendered in takamakie (raised-relief) using a combination of varying blues, black and silver nashiji (sprinkled design). The eyes are detailed in gilt and the bodies are inlaid with suzu (tin) imitating their camouflage markings

Onaga Tamotsu studied lacquer under Yamazaki Ritsuzan (1895-1969). In 1951 he began exhibiting at a national level with Nitten (the Japan Fine Art Exhibition). In 1964 his entry to the Nitten won the Tokusen (Nitten Speciality Prize) as well as the Hokuto award. The following year he was awarded mukansa (non-vetted status). During his career he also assisted as a judge for the Toyama Prefectural exhibition.

Onaga participated in numerous international exhibitions including the 1965 Berlin Fine Art Festival and in the same year he was honoured with a membership to the Gendai Kōgei Bijutsuka Kyōkai (Association of Contemporary Craft Artists). In 1966 he exhibited in Rome with the Nihon Gendai Kōgei Ten (Japan Contemporary Art Craft Exhibition) and again in London the following year.

In 1968 his work for the Gendai Bijutsu ten (Exhibition of Contemporary Fine Art) won both the Member's ward and the Minister of Culture Award. His work also won the Kikka Sho (Chrysanthemum Award) at the 1969 Nitten. From 1970 until 1976 Tamotsu continued to exhibit at the Nitten and the Gendai Kōgei Bijutsu Ten. In 1976 he received a commission from His Highness the Emperor, one of Japan's greatest honours.

Note: the back of the screen bears a label with the title along with the artist's address and name which reads: Toyamaken Himishi, Chizōmachi 13-3, 'Katsu' Onaga Tamotsu.

Exhibition: Works by the artist can be found in the collections of Nitten Association, Tokyo Prefectural Government, Tokyo; Toyama Prefectural Government, Toyama; Takaoka City Museum, Takaoka

A two-fold paper screen, Japan, Edo period, 17th century. nk and colour on a gold ground with keshi (poppies), 162.5 x 172.5 cm (64.3 x 68 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Keshi has two meanings, 'poppy' and 'erase', as this poem by Hokushi (d. 1718) so eloquently illustrates:

"Kaite mitari "I write, erase, rewrite,

Keshitari hate wa erase again, and then

Keshi no hana" a poppy blooms".

Literature: For a pair of six fold screens, one depicting mugi (wheat) and the other poppies in the collection of the Idemitsu Museum of Art see Nihon Byuōbu e Shūsei, Vol.7, Flowers & Birds, Four Seasons' Plants & Flowers, 1980, pp. 37-36, pl. 18.

Shiryū Morita, En (circle), 1967. Aluminium flake pigment in polyvinyl acetate medium and yellow alkyd varnish on paper and wood panel, 43.5 x 80 cm (17.3 x 31.5 in.). Signed, titled and dated with seal on a label affixed to the reverse, framed. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Morita Shiryū (1912-1999) was born in Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture and studied sho (calligraphy) under the influential and ground-breaking calligrapher Ueda Soukyū (1899-1968). Soukyū was a charismatic teacher introducing his talented pupils to avant-garde sho and its definition as the art of the line.

Having received numerous awards from important Japanese exhibitions such as the 1937 Inten (Japan Art Institute Exhibition) where he won the Tokusen silver award, Shiryū became more and more fascinated with the performance involved in the writing of sho and the similarities between the expressive calligraphic line and what was developing within the Abstract Expressionist art scene of the West. In 1948 he launched the magazine Shonobi (beauty of calligraphy) under the leadership of his master Ueda Sōkyū with the intention of promoting avant-garde sho.

The notion of abstraction had been part of the practice of East Asian calligraphy for many centuries, and Shiryū often wrote about the interplay between traditional Japanese calligraphy and abstract art in the West. These observations were catalogued in a second journal entitled Bokubi which was first edited and published by Shiryū in 1951 and featured an image of a calligraphic painting by Franz Kline on its cover. Distributed internationally, the journal became extremely influential within the Western art world, causing a further interest in the Japanese aesthetic followed by an array of collaborations and international exhibitions with European artists of the Abstract Expressionist movement such as Pierre Alechinsky (b.1927) and Georges Mathieu (1921-1912), and American artists Mark Tobey (1890-1976) and Franz Kline (1910-1962). With the help of such innovative publications and the possibility of international exposure, modern Japanese calligraphers such as Shiryū and fellow like-minded artist Inoue Yūichi soon became an international sensation.

In 1952, five disciples of Ueda Shoukyū including Shiryū co-founded the legendary Bokujinkai (Society of Ink People). He joined forces with Inoue Yūichi (1916-1985), Eguchi Sōgen (1919-), Sekiya Yoshimichi (b.1920) and Nakamura Bokushi (dates unknown) and together they further advocated the emancipation of the calligraphic line away from its traditional form and experimented using unorthodox materials. The beauty of the line itself is held as a self-evident attribute and the execution of the writing becomes the focus. Shiryū placed the performance of a piece at the centre of his definition of calligraphy. The kanji character is written in one defining moment with confident strokes. The calligrapher penetrates to a deeper level of understanding and the character is understood in a different, more profound way.

In terms of style and format, Morita Shiryū's works are groundbreaking. He preferred to use an oversized brush, working quickly across the surface. Whilst works such as the example presented here may appear to be executed using the rather slow process of Japanese lacquer, in actuality the metallic silver paint is applied swiftly onto the surface and later covered with a coat of fast drying yellow varnish achieving a similar effect. Shiryū's vigorous style often results in abstract forms which no longer appear to be recognisable characters yet they retain their original essence enhanced with a new vitality.

Provenance: Private collection, Southern Germany

Literature: For a pair of panels by the artist treated in a similar manner see: The Collection, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Kyoto 1993, p. 266, no. 30. For a large four-fold screen see Beyond Golden Clouds, Japanese screens from The Art Institute of Chicago and the Saint Louis Art Museum, pp. 196-97

Exhibition: Works by the artist can be found in the collections of Art Institute of Chicago, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Cincinnati Art Museum, Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri.

Figure of Amida Buddha seated in kekka fuza (lotus position) the hands in jō-in (meditation mudra), Japan, Muromachi period, 15th century. Gilt-wood. Height 50 cm (19.8 in.). Radio Carbon Dating Ref: RCD-8671. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

The head of this Buddha is adorned with crystals representing the byakugō (white spiralling hair) on the forehead and the nikkei-shu (red jewel on the protrusion on top of the Buddha's head).

This type of jō-in mudra is frequently used in Japanese Esotericism, especially in statues of the co-called Esoteric Amida. This particular one is characterized by circles formed with the thumbs and indexes and it stands for a specific rank in the Amida hierarchy.

The symbolism of the jō-in mudra is closely associated with the concept of complete absorption of thought by intense contemplation of a single object of meditation, in such a way that the bonds relating to the mental faculties to so-called 'real phenomena' are broken and the worshiper is thus enabled to identify himself with the Supreme Unity through a sort of super-intellectual raptus. In the jō-in the position of the hands is that of the adepts of yogic contemplation. Thus the jō-in symbolises specifically zenjō (ecstatic thought) for it is the gesture which indicates the suppression of all spiritual disquiet in order to arrive finally at the complete concentration on the truth.

The position of the hands in the mudra of concentration derives, in accordance with the tradition, from the attitude which the historical Buddha assumed when he devoted himself to final meditation under the Bodhi tree. This is the attitude he was found in when the demon armies of Mara attacked him. He was to alter it only when he called the earth to witness at the moment of his triumph over the demons. Consequently the position symbolises specifically the supreme mediation of the historical Buddha but also the Buddhist qualities of tranquillity, impassivity and superiority.

The circle formed by the fingers in this figure means the perfection of the Law because the circle is the perfect form. The formation of the two circles by the two hands representing respectively the world of the Buddhas (right hand) and that of Sentient Beings (left hand) indicates that the Law conceived by the Buddha is sustained by Sentient Beings who integrate themselves into it completely. The two juxtaposed circular shapes represent the accomplishment and the perfection of Buddhist Law in its relationship to all Beings. The right-hand circle symbolises the divine law of the Buddha, the left-hand circle, the human law of the Buddha. Side by side, the circles symbolise the harmony of the two worlds, that of Sentient Beings and that of the Buddha. The fingers are entwined; those of the left hand represent the five elements of the world of Beings and those of the right hand the five elements of the world of the Buddhas.

The two circles of this type of jō-in mudra also stand for the two aspects of cosmic unity; the Diamond World and the Matrix World. These circles are separated from each other because they are formed by two different hands. The circles are joined in this mudra to constitute a single unity which symbolises, by the form of their juxtaposition, the double aspect of a single world and the concept of All-One, the basic principle of Esotericism.

Belief in Amida as Lord of the Western Paradise rose in popularity during the late 10th century. Based primarily on the concept of salvation through faith, it was not only a religion which appealed to a broad range of people, but also a direct assertion of piety against the dogmatic and esoteric ritual of the more traditional Tendai and Shingon sects. In Amida's Western Paradise the faithful are reborn, to progress through various stages of increasing awareness until finally achieving complete enlightenment.

Images of Amida, lord of the Western Paradise, are known in Japan from as early as the seventh century. Until the eleventh century the deity was most frequently portrayed in a gesture of teaching and was worshipped primarily in memorial rituals for the deceased. However, in the last two centuries of the Heian period worshippers started to concentrate more on the Teachings Essential for Rebirth written by the Tendai monk Genshin (942-1017). The teachings describe the horrors of Buddhist hell and the glories of the Western Paradise that can be attained through nembutsu, meditation on Amida or the recitation of the deity's name.

Despite the apparent absence of formal variations in the images themselves, during the latter part of the Heian period important changes did occur in the nature of the rituals held in front of the Lord of the Western Paradise. By the twelfth century Image Halls dedicated to Amida were the ritual centres of most complexes. The function of memorial services was expanded so they benefited not only the dead, but also the living. Even rituals with no historical connection to the deity, such as the important services at the start of the New Year, were held there. Of particular significance were the novel ritual practices that were held to guarantee one's rebirth in Amida's Western Paradise. Some, such as the re-enactment of the descent of Amida, or the passing of one's last moments before death clutching a cord attached to the hands of the deity, were entirely new whilst others, including the use of halls dedicated to Amida as temporary places of interment, reflected the fusion of more ancient practices with doctrines of rebirth.

Provenance: Previously in the collection of Captain Jack Simpson and a private collection built between the 1960's and the 1970's.

Inoue Yūichi (1916-Tokyo-1985), Shoku (Belonging), 1976. Ink on paper, framed and glazed, 120 x 221.5 cm (47.3 x 87.3 in.). Seal 'Yūichi'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Inoue Yūichi (1916-1985) was born in Tokyo the son of a bric-a-brac dealer. In 1935 he graduated from Tokyo Prefectural Aoyama Normal School (present-day Tokyo Gakugei University) and almost immediately began working as an elementary school teacher at Yokogawa National School, Tokyo. Although he always aspired to become a painter, Yūichi was lacking the means to attend Art College. He therefore took evening painting classes and later turned to sho (calligraphy) due to its inexpensive materials and less formal instruction. In 1941 Yūichi began to study calligraphy under the renowned modernist calligrapher Ueda Sōkyū (1899-1968) and joined his master's avant-garde calligraphy group Keiseikai.

Ueda himself came from a modernist tradition of avant-garde calligraphers advocating the study of kanji (Chinese characters) by old Chinese masters, while at the same time being aware of contemporary international art movements. The emphasis of Ueda Sōkyū and the Keiseikai group was on the emotional expression of the self at the moment of writing. According to Ueda it is more embarrassing for a calligrapher to lack heart than technique.

In March 1945 Yūichi was on night duty at the Yokokawa National School where 1,000 people were taking shelter from a bombing raid by the American air force. The school was engulfed by flames and Yūichi was left as the sole survivor. This tragic near-death experience left him deeply scarred and he later described his ordeal in the calligraphic piece entitled Ah! Yokokawa National School, now in the collection of Unac Tokyo Inc.

'The town plunged into darkness is transformed into an incandescent sea…. All Kōto-ku is hell fire' he begins. 'A thousand refugees have no shelter and there is no exit.' Buried all night in a heap of corpses, Inoue concludes, 'At dawn, the fire is out. Silence is all. No cries'.

The horrors of war led Yūichi to dedicate his existence to the study of avant-garde sho and its promotion through journals such as Shonobi edited by Morita Shiryū, under the leadership of Ueda Sōkyū. He also became fascinated by modern western art and was regularly informed about action painting, abstract expressionism and the work of ground-breaking artists such as Franz Kline (1910-1962), Mark Tobey (1890-1976) and Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) by the pages of the Bokubi journal first published in 1951 by Morita Shiryū. Yūichi also befriended cultural emissaries such as Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), the international avant-garde artist Hasegawa Saburō (1906-1957) as well as various artists from the Gutai group.

In 1952 Yūichi along with four other disciples of Ueda Sōkyū; Morita Shiryū (1912-1999), Eguchi Sōgen (1919-) Sekiya Yoshimichi (b.1920) and Nakamura Bokushi (dates unknown) left Keiseikai to found the avant-garde calligraphy group Bokujinkai. The group's activities were documented in its journal Bokujin edited by Yūichi until its 50th issue. The group's goals were to liberate sho from orthodox conventions, to present it within a global perspective and to establish it as a contemporary artistic medium. The main emphasis was on individual study and unrestricted expression and so the group members refused to participate in large exhibitions or organisations in Japan.

Yūichi along with the rest of the Bokujinkai calligraphers abandoned traditional sho materials. This experimentation meant substituting the traditional fude (brush) with cardboard, sticks, hemp-palm and broom sized brushes. Sumi (ink) was also replaced with mineral pigments, oil paint, enamel and lacquer while canvas, wood, ceramic and even glass were used in place of washi (paper). Although their methods were totally innovative, the group pursued a rigorous re-evaluation of the fundamentals of ancient calligraphy and the timeless qualities of the calligraphic line from a contemporary, universal point of view.

These avant-garde calligraphers were not overly concerned that their renderings of kanji characters were legible or whether they had used a character at all. For the calligrapher the process of producing work is an existential involvement. The form gradually becomes 'his' during the writing and re-writing of the drafts when the initial or generally accepted meaning of the character may be forgotten. In Zen terms, the form becomes the calligrapher's koan (Zen dictum). The execution of a piece demands total absorption, both physical and mental, a complete giving of the self to the writing. Implicit in the piece is the whole experience the calligrapher goes through from initial spark, through confused wrestling with the line and form, to the absolute commitment of execution.

Writing in his journal Inoue proclaimed 'Turn your body and soul into a brush… No to everything! The hell with it! Paint with all your strength - anything, anyhow! Spread your enamel and let it gush out! Splash it in the faces of the respectable teachers of calligraphy. Sweep away all those phonies who defer to calligraphy with a capital C… I will bore my way through, I will cut my way open. The break is total.'

Unagami Masanomi, The Act of Writing:Tradition and Yū-Ichi Today, Ōkina Inoue Yū-Ichi ten/ Yū-Ichi Works 1955-85, Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art, 1989

However, after losing himself in this exhilarating cosmos of experimentation, of discarding the meaning and forms of kanji, Yuichi finally came to understand how marvellous they really were and from around 1957, free from the tradition of sho he devoted himself to action painting while adhering to the original characters so that he was to some extend restricted. Yuichi came to terms with the beauty in the form of the kanji, admitting worshiping the fatal nobleness of the Chinese characters.

Despite avant-garde calligraphy's superficial resemblance to abstract art the abstract within the calligraphic tradition is fundamentally different. An artist, should he choose, can reject or ignore the history of art. The avant-garde calligrapher however, cannot. He is working within a centuries-old discipline combining two visual languages, sho and abstract expressionism to convey deeply felt inner conflict and anguish.

When I write a particular character, I am often asked about the meaning of that character. At that point I usually say something that amounts to what you would find in the dictionary. And yet that is a mere entrance-way and no more. To give an explanation that goes as far as I have worked out with great efforts is impossible.

Provenance: Acquired by the previous owner from Japan Art, Frankfurt, Germany

Literature: YU-ICHI, Catalogue Raisonne, vol. 2, UNAC Tokyo, no. 76015.

Yasunobu Kanō (1614-1685), A pair of six-fold screens, Japan, Edo period, 17th century. Ink and colour on a gold ground. Each 166 x 374 cm (65.5 x W. 147.3 in.). Signed 'Tosahitsu Hōgen Eishin kore o shōsu' (A brush of the Tosa School. Authenticated by Eishin bearing the Hōgen title). Seals 'Hōgen' and 'Yasu'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Sceens with tsuru (cranes) and minogame (mythical terrapins) amongst matsu (pine trees) in a mountainous river landscape with a soft and round mountain line.

Kanō Yasunobu (1613-1685). Familiar names: Genshirō, Shirojirō, Ukyōnoshin. Gō (art names): Bokushinsai, Eishin, Ryōfusai, Seikanshi. Yasunobu was the son of Kanō Takanobu (1571-1618), who died when Yasunobu was a child. He studied in Kyoto under Kanō Kōi (d.1671) and his elder brother Tan'yū (1602-1674). Tan'yū later moved to Edo to found the Kajibashi branch of the Kanō family and was joined by Yasunobu who then became goyō eshi (official painter) to the shogun's court, founding the Makabashi Kanō School. Yasunobu was later adopted by Kanō Sadanobu (dates unknown) as his heir and was therefore regarded as the eighth-generation head of the main Kyoto Kanō line. A connoisseur of paintings, Yasunobu signed many certificates of authentication for Kanō paintings and later in his career was awarded the honorary title of hōgen (lit. Eye of the Law). One of his greatest accomplishments was painting the walls of the Shishinden Seiken of the Imperial Palace, Kyoto.

Tsuru (cranes) are among the premier symbols of longevity and good fortune in East Asia. For at least two millennia, the Chinese have viewed them as living to a great age and as being able to navigate between heaven and earth. In turn, these attributes have made them logical companions of sennin, the Taoist Immortals. Ancient Taoist alchemists believed that imbibing beverages made with crane eggs or tortoise shells would increase one's vital energies.

In Japan, the crane is the animal most frequently seen in the fine and applied arts. Although a common subject of painting, it is most closely associated with the New Year and with marriage ceremonies. In earlier times, when the Japanese still used circular brass mirrors and presented them on the occasion of a marriage, the crane was a favoured decorative theme due to its association with fidelity. In recent centuries, the crane has appeared on elaborately embroidered wedding kimono and among the mizuhiki (cord made from twisted paper) decorations presented at the time of betrothal.

The minogame (terrapin) of a thousand years, often paired with the crane as a symbol of longevity, is one of the four supernatural animals (tiger, dragon, phoenix, terrapin) of Chinese mythology. One representation of the terrapin has some of the features of the dragon, generally the head, but the most common is of the sacred animal with a long tail, said to grow when it is over five hundred years old, the origin of which is probably due to the fact that tortoises kept in ponds become covered with a parasitic growth of vegetable origin which resembled the Mino, or rain coat of the peasants, hence Minokame.

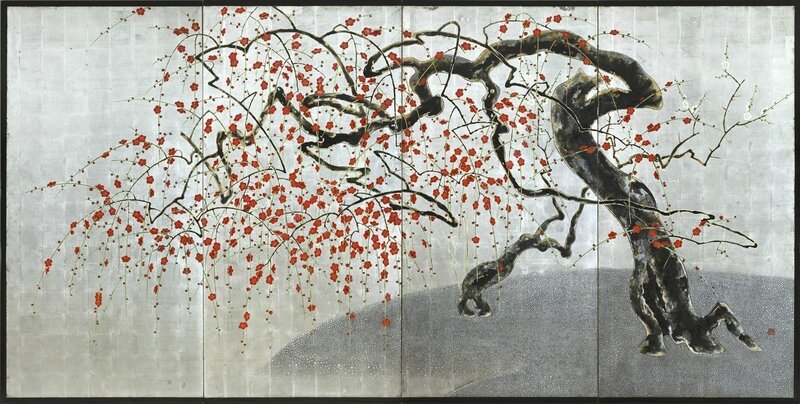

Four-fold paper screen, Japan, Taishō period, 20th century. Lacquer and colour on a silver ground, 187.5 x 370.5 cm (74 x 146 in.). Seal 'Shō'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Scene with two gnarled ume (plum trees) in full bloom. The foreground is dominated by the larger of the two trees which has red blossom while the smaller tree in the background has white. Both trees sit atop a knoll in a Japanese rock garden rendered in moriage (raised design).

In Japan, plum blossoms is celebrated as a harbinger of spring due to it blooming towards the end of January. The blooms appear when there is still snow on the ground, and are considered a symbol of strength and overcoming adversity. It is also known as one of the shōchikubai (lit. pine-bamboo-plum) or saikansanyū (lit. three friends of winter) since the beginning of the 13th century. The plum also symbolises longevity as the blossoms continue to appear on old gnarled branches of ancient plum trees, their sweet fragrance improving with age.

Paintings of blossoming plum offer artists excellent opportunities to demonstrate the calligraphic flair of their brushwork. Since plum blossoms have multiple connotations in Chinese and Japanese cultures their representation offers numerous possibilities of symbolic expression. As one of the earliest spring-flowering trees, plum symbolises rejuvenation and vitality. Because the tree is hardy and often long lived, its branches also signify endurance and perseverance. In other contexts, the delicate white blossoms were often associated with purity and feminine gracefulness. With so many possible meanings, paintings of plum blossom could be displayed on many occasions, a versatility that was no doubt part of the genre's long-lasting appeal.

It would seem likely that the pairing of red and white as seen in this iconic imagery has its roots in the Gempei war between the Taira and Minamoto clans at the end of the 12th century, with the victorious Minamoto founding the Kamakura period (1185-1333). This war and its aftermath established red and white, the respective colours of the Taira and Minamoto, as Japan's national colours. Today, this combination of colours can be seen in sumo competitions, various traditional activities and on the national flag of Japan.

Exhibition: The back of the screen bears two exhibition labels which read:

Lower label 'Ume, Kawasaki Shōzō (Plum, Kawasaki Shōzō)'

Upper label 'Daimei; ume. Meishi; Kawasaki Shōzō. Dai; ni jyūni gō (Title; plum. Name; Kawasaki Shōzō. No. 22)'.

A six-fold paper screen, Japan, Edo period, 17th century. Ink and colour on a gold ground with hinageshi and shirogeshi (red and white poppies), 113 x 280 cm (44.5 x 110.3 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Keshi has two meanings, poppy and erase, as this poem by Hokushi (d. 1718) so eloquently illustrates.

Kaite mitari I write, erase, rewrite,

Keshitari hate wa erase again, and then

Keshi no hana a poppy blooms.

Literature: For a pair of six fold screens, one depicting mugi (wheat) and the other poppies in the collection of the Idemitsu Museum of Art see Nihon Byuōbu e Shūsei, Vol.7, Flowers & Birds, Four Seasons' Plants & Flowers,1980, pp. 37-36, pl. 18.

Figure of Jizō Bosatsu standing on a lotus base and adorned with a round mandorla, Japan, Kamakura period, 13th century. Carved wood. Height figure and stand 72 cm (28.5 in.). Height figure 46 cm (18.3 in.). Radio Carbon Dating Ref: RCD-8890. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

The face, hands and feet are finished in white while the robes are elaborately decorated with coloured pigments and gilt. The head has gyokugan (inlaid crystal eyes) and the forehead is adorned with a crystal representing the byakugō (white spiraling hair). The shakujo and hoju which are usually carried by Jizo figures are missing. The fingers of both hands are repaired.

Jizō Bosatsu, represented as a simple monk, has existed in Japan since the eighth century, becoming widely worshipped by the masses at the end of the Heian period (794-1185) with the rise of Pure Land (Amida) Buddhism. He is usually shown in the guise of a shaven-headed priest with a kyōshoku (breast ornament) and carrying a hōju (a jewel which grants desires) in his left hand and a shakujō (priest staff) in his right. As an attendant of Amida his powers include the saving of souls condemned to the various Buddhist hells and the intervention with Yama, the Master of Hell, on behalf of those reborn in each of the six realms of transmigration. He guards travellers safely on their way, protects warriors in battle, watches over the safety of children, families and women during pregnancy.

Heian beliefs about Jizō, a compassionate Bodhisattva, involved widespread belief of the Three Periods of the Law known as the Days of the Dharma (the Buddhist teachings). This was an all-encompassing concept of society's rise and fall that originated in Indian Buddhism and later became widespread in China and Japan. It foretold the world's ultimate decay and the complete disappearance of Buddhist practice. At the time, the Days of the Dharma in Japan were divided into three periods.

The first phase, the Age of Shōbō, was said to last 1000 years after the death of the Buddha. It was believed to be a golden period during which followers had the capacity to understand the Dharma. The second phase, the Age of Zōhō, was also to last 1000 years during which Buddhist practice would begin to weaken. The third and final phase, the Age of Mappō, lasting 3,000 years was when Buddhist faith would deteriorate and no longer be practiced. In Japan the Age of Mappō was said to begin in 1052 AD, and a sense of foreboding thus filled the land, with people from all classes yearning for salvation. This belief lead to a comprehensive increase in the popularity of Jizō as the only deity man could petition in these lawless centuries for relief from pain in this life and the next.

The naturalistic treatment of the figure represented here stems from a tradition of Japanese portrait sculpture which developed in a Buddhist context and was never completely separated from the religious setting. From the beginning the majority of the subjects portrayed were religious personages, whether legendary or historical. The portraits of venerated monks, which form the body of Japanese portrait sculpture, were appreciated as objects of aesthetic value from as early as the Nara period (645-781). This tradition of naturalistic representation can also be seen in sculptures of Buddhist deities produced at the time.

Literature: For similar example of a Jizō figure held in the collection of Tōdai-ji, Nara see Kamakura. The Renaissance of Japanese Sculpture 1185-1333, 1991, pl.14 and another example held in the collection of Bushin-ji, Aisho see: Omi: Spiritual Home of Kami and Hotoke, 2011, p.217, pl. 37.

Repoussé half figure of Guanyin (Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara), Sino-Tibetan, Qing dynasty, 18th century. Gilt copper. Height 59 cm (23.3 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

The figure is draped in a flowing robe, tied at the waist with a bow. Jewel strings with florets and tassels adorn the garment and are inlaid with semiprecious stones. Avalokiteshvara is an esoteric form of the Bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas and became widely employed in tantric visualisations. This bodhisattva is portrayed in different cultures as either female or male and corresponds to the Chinese Goddess of Mercy Guanyin and the Japanese Kannon.

According to Mahāyāna Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara is the bodhisattva who vowed to assist sentient beings in times of difficulty and to postpone his own Buddhahood until he has assisted every sentient being in achieving liberation from suffering.

The Lotus Sutra (3rd century) is generally accepted to be the earliest literature teaching about the doctrines of Avalokiteshvara and is the most popular and influential Mahayana sutra appropriated by many important Buddhist Doctrines such as the Tiantai, Tendai, and Nichiren amongst others. In its 25th chapter, Avalokiteshvara is described as a compassionate bodhisattva who hears the cries of sentient beings and works tirelessly to help those who call upon him. A total of 33 different manifestations of Avalokiteshvara are described, including female manifestations, all to suit the needs of various beings. This earliest source often circulates separately as its own sutra, called the Avalokiteshvara Sūtra and is commonly recited or chanted at Buddhist temples in East Asia and is considered good karma.

Provenance: Provenance: Previously in the collection of Ross Levett, Maine USA and E. Van Vredenburgh, Brussels, Belgium.

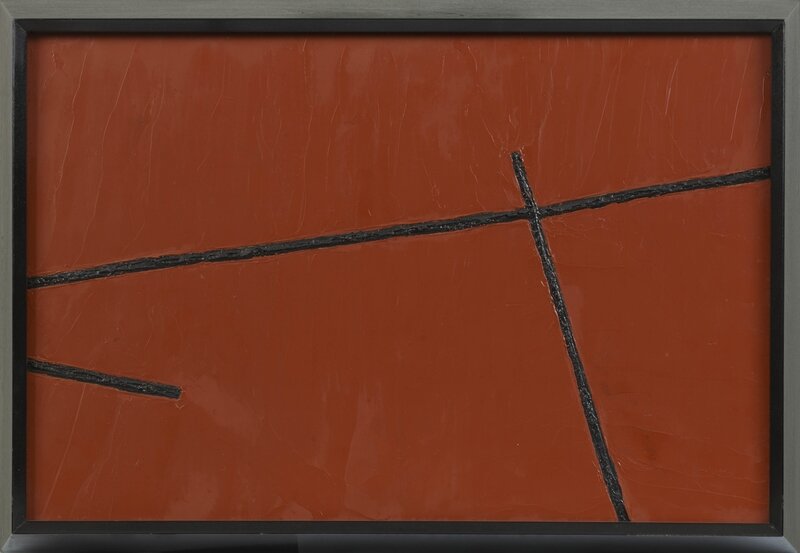

Takeo Yamaguchi (Seoul 1902-1983 Tokyo), Kō (Suburbs), 1972. Oil on board, 31 x 44.5 cm (12.3 x 17.8 in.). Signed, titled and dated in Japanese on a label affixed to the reverse, framed.

Yamaguchi Takeo (1902-1983) was born in Seoul Korea. He moved to Tokyo in 1921 at the age of 19 and began studying painting under Okada Saburosuke (1869-1939). The following year he was accepted into the increasingly popular department of Western painting at the Tokyo Art Academy. His course of study surveyed all the major European avant-garde movements of the previous two decades. Yamaguchi was particularly impressed by Cubism for its reduction of form and colour to a flattened and two dimensional painted surface. After graduating in 1927, Yamaguchi moved to Paris and continued his studies of avant-garde European painting where he worked at the studio of the sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967) and became friends with painter Ogisu Takanori (1901-1986).

In 1931 Yamaguchi returned to Tokyo by which time his painting had evolved and reached a certain degree of abstraction where his figures had dissolved into thick black lines and the landscape backgrounds had morphed into coloured blocks. This metamorphosis however, kept his art outside the two main categorisations used in Japan during the pre-war period, which strictly divided painting into either the Western figurative style of oil painting or the nihonga Japanese style. This antiquated system led Yamaguchi along with other likeminded artists such as Yoshihara Jiro (1905-1972) and Yamamoto Keisuke (1911-1960) to form the Nika-kai group also known as Kyūshitsu-kai (Society of the Ninth Space) in 1933. The group, which opposed the dual categorisation of painting, appealed to Yamaguchi who on his return to Japan sought a more permissive environment in which to continue painting towards avant-garde modernism and abstraction.

During the years of the Second World War Yamaguchi had been quietly and steadfastly creating severe non-figurative forms until his ascension to critical acclaim in 1954 when he was awarded a prize at the Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition, Tokyo. Thus in the mid-1950's it was almost without warning that Yamaguchi found himself a sudden pioneer of a revolutionary trend: pushed to the very front ranks of Japanese abstract artists with his work exhibited in important international exhibitions including the inaugural exhibition of the Guggenheim, New York in 1959. He was involved in the Society of Avant-garde Japanese Artists and in 1953 founded the Japanese Abstract Art Club. In 1954 he became professor at the Mushashino Art Academy and later that same year published a book entitled From Primitiveness to Modern Design.

His work from that period onwards was exclusively painted in multiple thick impasto layers using only three colours; black, ochre and deep burnt sienna. The texture and depth of tone achieved from the multiple layering of pigments gives Yamaguchi's work an earth like quality and is considered to be an homage to the soil of his birthplace the Korean peninsula. Yamaguchi strived to interact with the innermost framework and structure of a subject, merging figure and ground, seeking to awake in his forms the soul and depth of nature.

Literature: Yamaguchi Yakeo Sakuhin Shyū, Catalogue Raisonne, Kōdansha 1981, no. 370

Exhibition: Works by the artist can be found in the collections of Guggenheim Museum, New York; Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Menard Art Museum, Nagoya; Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, Shimane Art Museum, Museo de Arte Moderna, Sao Paulo; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Municipal Museum, Kagoshima; Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura.

Hanging kōro (incense burner) in the form of two saru (gibbons), each reaching for a single fruit of kaki (persimmon) on a branch with their a long, slender arms, Japan, Edo period, 19th century. Bronze, 81 x 9.5 x 10 cm (32 x 3.8 x 4 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Macaques once inhabited much of Japan and their interactions with humans were frequent. Saru (monkey) thus became a natural focus of the local folklore and religion. As illustrated by one of the many sacred Shinto myths the Japanese held saru in high regard. In the ancient texts of Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, 711AD), when the sun goddess Amaterasu sent her grandson Ninigi no Mikoto down from heavens to rule Japan, the grandson was met midway by an escort deity named Sarutahiko no Mikoto (prince monkey). This deity is generally considered to be connected to the monkey and as an escort deity it is known as a guardian of roads, travellers and guidance.

With the transition from the medieval period to the early feudal era in Japan, the monkey's religious significance declined while its reputation grew for being clever and mischievous as well as deceitful and conniving.

Although only the macaque is native to Japan, it is often the slender-armed, graceful gibbon of China that is depicted in Japanese art. This is especially true in art inspired by Zen tradition and Chinese exemplars.

Mask of Usobuki, Japan, 16th -17th century. Wood, 19 x 15 cm (7.5 x 6 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Usobuki, also known as Hyotoko, is the male character of traditional Japanese Kyōgen and is usually paired with the female character Okame. Usobuki is often referred to as "the whistler" due to his facial expression of pursed lips.

Koro (incense burner) in the form of a cat, Japan, Edo period, 17th century. Bronze, 11 x 17 x 11 cm (4.5 x 6.8 x 4.5 in.). Inscribed 'Da-Ming, Xuande nianzhi' (Made during the reign of Xuande emperor of the Great Ming Dynasty. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Although this very unusual model of a seated cat bears an impressed reign mark of Xuande (1425-1435) it is almost certainly of Japanese manufacture. The head turning backwards and a collar tied around the neck.

Japan acquired not only the domestic cat (neko) from China but also superstitions about the animal, including the belief that it disguised itself in human, usually female, form. This tradition is reflected in Edo-period woodblock prints of a fierce and huge witch-cat being slain by Inumura Daikaku, a hero of the Hakkenden.

The only widespread emblematic use of the cat in Japanese design involves the maneki-neko, the enticing or beckoning cat. Originally this term referred to a cat's supposed ability to charm and bewitch passers-by. However, these negative connotations gave way to an auspicious interpretation, and today the maneki-neko symbolizes a merchant's success in attracting customers as well as house-holder's financial good fortune. Such cats, usually crafted of papier-mâché or pottery, sit upright, with one paw lifted in a welcoming gesture. They are frequently portrayed with a charm hanging from the neck or a placard on the chest that has the three ideographs for ten million ryo. The ryo, is a monetary unit used during the Edo period and was equivalent to eighteen grams of gold.

Masakichi Kobayashi, Flower vessel of bulbous form with a short rectangular neck, Japan, Shōwa period, 20th century. Bronze, 19 x 16.5 x 12.5 cm (7.5 x 6.5 x 5 in.). Signed 'Masakichi saku' (Made by Masakichi). Tomobako (original box) inscribed: Lid 'Chudō Henko' (Cast bronze round flask). Lid interior 'Masakichi saku' (Made by Masakichi). Seal 'Masakichi'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art.

Nantenbō Nakahara (Karatsu 1839-1925), Kakemono (hanging scroll), Japan, Taishō period, 1918. Ink on paper with an ensō (circle) containing calligraphy. Scroll 110.5 x 31.5 cm (43.8 x 12.5 in.). Painting 31.5 x 29.5 cm (12.5 x 11.8 in.). Inscribed 'Yo no naka no maruki ga nakani umarete wa hito no kokoro mo maruku koso mote Born within the ensō of the world the human heart must also become an ensō'. Signed 'Nanajyūkyū ō Nantenbō sho' (Painted by Nantenbō at the age of 79). Seals: Right 'Nantenbō'; Upper 'Tōshū'; Lower 'Hakugaikutsu. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Ensō is a Japanese word meaning circle and a concept strongly associated with Zen. Ensō is one of the most popular subjects of Japanese calligraphy even though it is a symbol and not a character. It symbolises the Absolute, enlightenment, strength, elegance, the Universe, and the void; it can also symbolise the Japanese aesthetic itself. As an 'expression of the moment' it is often considered a form of minimalist expressionist art.

In Zen Buddhist painting, ensō represents a moment when the mind is free to simply let the spirit create. The brushed ink of the circle is usually done on silk or paper in one movement (but sometimes the great Bankei used two strokes) and there is no possibility of modification: it shows the expressive movement of the spirit at that time. Zen Buddhists believe that the character of the artist is fully exposed in how he or she draws an ensō. Only a person who is mentally and spiritually complete can draw a true ensō. Achieving the perfect circle, be it a full moon or an ensō is said to be The Moment of Enlightenment.

While some artists paint ensō with an opening in the circle, others complete the circle. For the former, the opening may express various ideas, for example that the ensō is not separate, but is part of something greater, or that imperfection is an essential and inherent aspect of existence (the idea of broken symmetry). The principle of controlling the balance of composition through asymmetry and irregularity is an important aspect of the Japanese aesthetic Fukinsei, the denial of perfection.

This particular ensō features an inscription and signature contained within itself as well as smaller circles used to indicate the words 'circle' and 'round' thus symbolising the infinite movement of the circle and its birth within itself, the world and the human psyche.

Literature: Works by the artist can be found in the collections of Freer and Sackler, the Smithsonian's Museum of Modern Art, Washington D.C.; the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; Gitter-Yelen, New Orleans Museum of Art.

Exhibition: Margate, Turner Contemporary, Seeing Round Corners, 21 May - 25 September 2016.

Rengetsu Ōtagaki (1791-Kyoto-1875), Teapot, Japan, Edo/Meiji period, 19th century. Pottery, 12 x 4.5 cm (4.8 x 2 in.). Lid interior signed 'Rengetsu. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Inscribed: Hinazuru no yukusue tōki koe kike ba miyo wo chitose to utau nari keri. As I listen to the fledgling crane with its long future, it sings: 'The rein of the Emperor will last forever'.

Tomobako (original box) inscribed: Lid: Rengetsu rōni saku, ko kyōsu ichi (Made by the old nun Rengetsu, a small tea pot, one item.). Lid interior: Uta Hinazuru no yukusue un'nun. Jinko-in nushi, Koen kore wo mitomu (A poem about a young crane's future, authenticated by (Priest) *Kōen, of the Jinkōin temple). Seal: Kōen.

*Tokuda Koen (b.1935) was the head Priest of Jinkō-in Temple and was the chief authenticator of Rengetsu's works in modern times.

The lid with a pine cone finial and the body incised with a poem.

Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875). Rengetsu was in her lifetime a Buddhist nun, poet, calligrapher, potter and painter. Shortly after her birth in Kyoto to a samurai family with the surname Todo, she was adopted by Otagaki Mitsuhisa who worked at Chion'in, an important Jōdo (Pure Land) sect temple in Kyoto, and was given the name Nobu.

In 1798, having lost her mother and brother, she was sent to serve as a lady-in-waiting at Kameoka Castle in Tanba, where she studied poetry, calligraphy and martial arts, returning home at the age of 16 to marry a young samurai named Mochihisa. They had three children, all of whom died shortly after birth; in 1815 Mochihisa also died.

In 1819 Nobu remarried, but her second husband died in 1823. After enduring the tragic loss of two husbands and all her children, Nobu, only 33 years old, shaved her head and became a nun, at which time she adopted the name Rengetsu (Lotus Moon). She lived with her stepfather, who had also taken vows, near Chion'in. After his death in 1832 Rengetsu began to make pottery, which she then inscribed with her own waka (31-syllable classical poetry) and sold to support herself.

In 1875, having led a long and exceptional life, Rengetsu died in the simple Jinkōin tearoom in Kyoto where she had lived and worked for ten years. Jinkōin Temple is a Shingon School temple (Esoteric Buddhism); Rengetsu was ordained as a nun in the Pure Land School (Jōdo Shū) but she also studied and practiced Zen and Esoteric Buddhism.

The delicate hand-built tea utensils that Rengetsu inscribed with hauntingly beautiful poems are unique combinations of poetry, calligraphy and pottery; they were as highly prized in her own lifetime as they are now. Rengetsu is also known to have inscribed her poems on utensils made by other Kyoto potters. In addition to ceramics, she also produced numerous gassaku (jointly created artworks) in the form of paintings, hanging scrolls, and calligraphic works with fellow literati artists and writers.

Literature: For similar teapot in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia see Black Robe White Mist, art of the Japanese Buddhist nun Rengetsu, p. 65, pl. 79.

Kakemono (hanging scroll), Japan, Kamakura period, 13th-14th century. Silk on paper with ink and colour. Scroll 102 x 30.5 cm (40.3 x 12 in.). Painting 28 x 15 cm (11 x 6 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

with Jizō Bosatsu. He is wearing floating gold robes applied in kirikane (cut gold) and is seated in kekka fusa (lotus position) on a lotus throne. In his right hand he holds a staff with six rings and in the left hand a hōju (the jewel which grants desires). Separate circular overlapping halos surround the head and the body.

Images of Jizō Bosatsu (lit. Womb of the Earth), represented as a simple monk, have existed in Japan from the eighth century on, becoming widely worshipped by the masses at the end of the Heian period with the rise of Pure Land (Amida) Buddhism. He is often shown, particularly in paintings, as an attendant of Amida. His powers include the saving of souls condemned to the various Buddhist hells, guarding travellers safely on their way, protecting warriors in battle, watching over the safety of families and aiding women in pregnancy and childbirth.

Jizō is often shown carrying a staff with six rings, which he shakes to awaken us from our delusions. The six rings likewise symbolize the Six States of Desire and Karmic Rebirth and Jizō's promise to assist all beings in those realms. In Japanese tradition, the six rings, when shaken, make a sound in order to frighten away any insects or small animals in the direct path of the pilgrim, thus ensuring the pilgrim does not accidentally kill any life form. In Chinese traditions, Jizō shakes the six rings to open the doors between the various realms.

Kenzo Ochi (Ehime prefecture 1929–1981), Flower vessel. Uchidashi (hammered) iron, 35.5 x 47.5 cm (14 x 18.8 in.). Seal 'Ken'. Tomobako signed 'Kenzō saku'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Ochi Kenzō (1929–1981) was born in Ehime prefecture and went on to study metalwork at Tokyo University of Fine Arts, graduating in 1953. Ochi chose to sculpt his pieces in iron using the uchidashi (hammered metal) technique and soon gained recognition from the Japanese art world with his iconic creations. The following year he exhibited at the 10th Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition). This affiliation continued for many years and Ochi received numerous prizes for his exhibits throughout his short yet illustrious career.

Ochi was also keen to share his skills and in 1956 he returned to the Tokyo University of Fine Arts first as a part-time teaching assistant and from 1959 gained a full-time position. His teaching career continued to develop and in 1965 he joined Tokyo Gakugei University as a full-time lecturer and was then promoted to Assistant Professor in 1969 before finally becoming Professor of metalwork in 1976.

Whilst dedicated to teaching Ochi remained active as an artist exhibiting regularly and winning many prizes which included The Yomiuri Newspaper award in 1964 for his exhibit at the annual Japan Modern Crafts Exhibition and the Award of the Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1965. In the following years, as he matured as an artist, he was invited to become a judge for both the Nitten and Japan Association of Modern Craft Artists Exhibitions respectively.

The iron sculptures of Ochi Kenzō are fine and light, their rounded organic forms, jutting spires and tubular sections appear to defy gravity irrespective of their material. Ochi was one of the most influential metalwork artists of his time who due to his relatively short life and the extremely labour-intensive process of uchidashi only produced a small body of work, much of which is now held in the collections of major Japanese museums and institutions.

Literature: For a similar example from see Tree Thoughts in the collection the National Museum of Modern Art, Ochi Kenzo 1929-1981, Tokyo 1970, pl.16, p17

Exhibition: Works by the artist can be found in the collections of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; Tokyo University of Fine Arts.

A kanshitsu natsume (tea jar) imitating a pottery natsume, Japan, Edo period, 19th century. Dry lacquer, with a brown treacle glaze, 6.5 x 2 cm (2.8 x 2 in.). © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Sōtatsu Tawaraya, A two-fold paper screen, Japan, Edo period, 17th century. Gold, silver and ink on a buff ground, 173 x 195 cm (68.3 x 77 in.). Seal 'Inen'. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Scene depicting an autumnal scene with kiku (chrysanthemum), hagi (bush clover), susuki (papmas grass), morokoshi (sorghum) and nasu (aubergine).

The 'Inen' seal is regarded as a trademark of the Tawaraya workshop, led by Tawaraya Sōtatsu (died ca.1640), who co-founded the Rimpa school with Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558-1637). Sōtatsu is known to have used the 'Inen' seal himself, although only until he was granted the honorary title of Hokkyō in or around 1624. Hokkyō literally 'Bridge of the Law', is the third highest honorary title, initially bestowed upon priests and then from the 11th century on Buddhist sculptors. From the 15th century the title was also given to artists. Around 1620 the leading pupil of the Tawaraya workshop was given the "Inen" seal by Sōtatsu and is referred to as the 'Painter of the Inen seal'.

Early Japanese records suggest that kiku (chrysanthemum) were introduced from China in the pre-Nara period (pre-710), with the focus at that time on the plant's medicinal uses. Various varieties of the plant are still used today in Asian herbal medicine to detoxify the body and treat fever, liver problems and eye disease.

By the Heian period (794-1185), kiku were cultivated as ornamental, but the plant's prophylactic qualities were still celebrated. In the Edo period (1615-1868), the Choyo Festival was made one of the officially recognized seasonal Five Festivals. This autumn festival is held on the ninth day of the ninth month and because this is the season in which kiku flourishes, it is also called the Chrysanthemum Festival. During the Edo period, beginning with each daimyō, people gathered at Edo Castle, held a Choyo ceremony and celebrated it with kiku sake, wine in which kiku petals had been steeped. Court nobles also rubbed their bodies with the night dew of kiku as it was believed to deter evil spirits and to prolong life.

Kiku viewing was also a pastime for people living in Edo. The Edo period was a time when gardening boomed and from the early Edo period, as enthusiasm for gardening grew, different types of various species were produced and flower shows for new types of kiku called kikuawase (chrysanthemum matching) were also held amongst the people.

Japanese interest in kiku as a theme for poetry developed during the Heian period. At that time, with the evolution of a native artistic sensibility heavily influenced by the passing seasons, the flower gained its place as one of the premier symbols of autumn. In many instances, kiku appear in ensemble motifs with all or some of the Seven Grasses of Autumn, and it is sometimes included in enumerations of this group.

The first use of kiku as a symbol of the Japanese imperial family occurred in the thirteenth century. Later many commoners also used the flower as a family crest, and a Matsuya store catalogue of 1913 included ninety-five crest designs based on kiku.

Literature: For a set of four fusuma doors incorporating morokoshi (sorghum) in the composition and bearing the same seal in the collection of the Kyoto National Museum see Rimpa Painting Vol. I, Flowering Plants and Birds of the Four Seasons, 1989, pp. 56-57, pl. 25. For a pair of two fold screens by Kitagawa Sōsetsu (active 1639-1650) of a similar composition and bearing an Inen seal in a private Japanese collection see Rimpa Painting Vol. II, Seasonal Flowering Plants and Birds, 1990, pp. 118-119, pl. 198. For a poem scroll painted in a similar manner using gold and silver and bearing the same seal by Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558-1637) in a private Japanese collection see Rimpa , Tokyo 1973, p. 34, pl. 6.

Tadasky (Tadasuke) Kuwayama (Nagoya, 1935), C-154, 1965. Oil on canvas, 142.5 x 142.5 cm (56.3 x 56.3 in.). Signed, titled and dated on the reverse and framed. © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Tadasky (Tadasuke Kuwayama b.1935) was born in Nagoya the youngest of eleven sons. His father owned a successful building company which specialised in constructing Shinto shrines in the traditional manner. This is a privileged and respected occupation demanding the highest level of construction. Tadasky spent many hours in the family carpentry workshop and learned carefully guarded carpentry skills and techniques from the talented craftsmen working under his father. The symmetry of Shinto architecture left a lasting impression and he drew upon this influence and knowledge throughout his career.

Looking at one of my paintings is for me like entering a traditional Shinto shrine. Because they are both so simple and symmetrical, the impact is very powerful. I am not a believer, but some people would call this experience "spiritual."

Interview to Julie Karabenick, 2013

Japanese art schools and academies in the early 1960's were still quite traditional and many of the new emerging styles of art were often discouraged. Tadasky believed he would not be able to follow his dream and paint using mainly geometric forms and therefore in 1961 he decided to emigrate to the USA on a student visa. Shortly after his arrival in America he entered a competition held at the Art Students League where he won first prize and was immediately granted a scholarship. He was also spotted by the director of Brooklyn Museum Art School who offered him a further scholarship. However, regardless of receiving free tuition Tadasky needed to supplemented his income and did this by using his carpentry skills to make stretchers for other artists such as Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein and the New York based galleries Betty Parsons and Leo Castelli.

Tadasky was deeply impressed by the modern forms of New York's architecture and was inspired to dedicate his painting to geometric shapes, particularly the circle. He especially enjoyed his studies at the Brooklyn Museum Art School as they allowed him to work from his home studio where he could spend long hours painting without the constrains of the School's schedule. In order to realise his dream of painting as many concentric perfect circles as possible he developed a particular tool. Tadasky constructed a turntable-like surface where the canvas would lie flat with a narrow bench hovering over it for him to sit on. He would then carefully place his paintbrush on the surface of the canvas and paint while steadily revolving it; a process which demands great steadiness, concentration and control. By 1964 he managed to master his wheel and this allowed him to start experimenting with the juxtaposition of vivid colours in concentric circles.

In the same year Tadasky's work was featured in Life magazine's article, Op Art: A dizzying fascinating style of painting and began to be closely associated with the Optical Art movement. William Seitz (1914-1974), curator of the Museum of Modern Art, visited Tadasky's studio and chose six paintings for the seminal MoMA exhibition 'The Responsive Eye' in 1965. Immediately his work was obtained by many important art collectors, MoMA acquired two of his paintings for their permanent collection and the famous Kootz Gallery seeing his potential held two very successful solo shows.

In 1966 he returned to Japan and held a solo show at the Tokyo Gallery, Tokyo. The exhibition was attended by Yoshihara Jiro (1905-1972) the founder of the Gutai movement who bought several pieces. The two found common ground through their preoccupation with the circle and Tadasky was invited to join the now famous Gutai movement giving him the opportunity to hold a solo show at the Gutai Pinacoteca in Osaka later that year.

In 1969 Tadasky bought a 7-story building in Soho, New York where he lived and sublet spaces to other artists. In 1972 he built a large kiln in the basement of the building which became the Grand Street Potters, the largest kiln in New York at that time. During that period he experimented with pottery but soon returned to painting and begun to use airbrush techniques giving a soft diffused finish to his until then crisp circles. Between 1986 and 1993 he lived and worked in Japan where he continued using airbrushed circles suffused with dots and overlapping squares.

The creation of these works requires deep concentration before the start and Tadasky states he holds a clear picture of the finished work in his head throughout the creative process not stopping until completed. For him the painting process is a joyful experience.

When writing about Tadasky's work, Donald Kuspit (b.1935), the renowned American art critic, emphasises: the circles are pure modern abstractions, yet the combination of the brightly coloured concentric rings centred in the square canvas is reminiscent of mandalas, invoking a spiritual connotation; a Zen sensibility.

Tadasky is still active today and continues to use his original turntable and bench technique, maintaining studios in Chelsea, Manhattan and in Ellenville, New York.

Provenance: Feigen - Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles

Exhibition: For a similar example exhibited in the MoMA exhibition of 1966 curated by Dorothy Miller and William Lieberman see The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture, New York 1966, p. 93 and for a video interview go to http://www.hallmarkartcollection.com/videos/

Gregg Baker Asian Art at TEFAF New York Fall 2017, Stand: 72. Primary Address: 142 Kensington Church Street, London, W8 4BN, United Kingdom. T +442072213533 - info@japanesescreens.com - http://japanesescreens.com/

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)