The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art at Christie's London, 7 november 2017

Lot 160. A bronze ritual wine vessel and cover, you, Late Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 13 in (33 cm) high. Estimate 80,000 - GBP 120,000 (USD 105,600 - USD 158,400). Price realised GBP 248,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

Michael Michaels (Born: Magdeburg, Germany 1907 - Died: London, England 1986)

In 1933, when the Nazis came to power in Germany, Michael Michaels fled to Britain as a penniless refugee. His first job was working in a raincoat factory owned by the Hammerson family, who recognised his determination to improve himself. With the help of his wife Charlotte, who he met in London, he set up a tent and camping goods company. Its success derived from his energy, resourcefulness and determination.

Once established financially, he was able to devote his time and intellectual energy to expanding his horizons. He was fascinated by antiquities of all cultures, especially how people with limited access to materials and technology could fashion beautiful pieces. He travelled widely in Europe and Israel seeking out great museums and important sites. It was only in the late 1960s that serendipitously he encountered archaic Chinese bronzes. He fell in love with their shapes, patina and historical background.

He immersed himself in learning about archaic Chinese bronzes with the same determination that had led him to commercial success. Michael Michaels became a self-taught expert with an eye for the authentic and beautiful. He spent hours in the British Museum, learning from Jessica Rawson and others; gaining an understanding of the nature of the pieces, the symbolism, the method of their manufacture, their uses and how to differentiate between seemingly similar artefacts. He was so grateful to the British Museum for their assistance that he donated to the museum an important late Shang Dynasty fang yi, from his collection. As other collectors heard about Michael’s collection and wide knowledge, he was increasingly asked for advice, which gave him much pleasure. Later, he visited the great collections in New York and San Francisco to learn more. Sadly, he never visited China.

He felt that each item he bought needed to ‘speak’ to him. He loved the idea that these beautiful pieces were so treasured by their owners that they were buried with them. Each item needed to have beauty and symmetry, but also a back story to which he could relate. He understood that China had given the world so much beauty and innovation, and would one day again astonish the world.

His wife Charlotte is now 100, and she and her family recognise that the time has come for these beautiful objects to find new homes in which they can be appreciated and loved.

Lot 156. A bronze ritual wine vessel, jue, Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 8⅜ in (21.3 cm) high. Estimate: GBP 10,000-GBP 20,000 (USD 13,200 - USD 26,400). Price realised GBP 25,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017

The body is cast with an intricate band comprising two stylised taotie masks, one divided to the centre with a vertical flange, the other with a pictogram cast beneath the curved handle surmounted by a buffalo head. A three-character inscription reading ran fu gui is cast under the handle. The surface is of a greyish-green tone with areas of malachite encrustations. The body is cast with an intricate band comprising two stylised taotiemasks, one divided to the centre with a vertical flange, the other with a pictogram cast beneath the curved handle surmounted by a buffalo head. A three-character inscription reading ran fu gui is cast under the handle. The surface is of a greyish-green tone with areas of malachite encrustations.

Provenance: The Property of Richard C. Farish, Esq.

Sotheby's London, 6 April 1976, lot 3.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: The three-character inscription beneath the handle ran fu gui may be read 'dedicated to Father Gui of the Ran clan'.

Compare the current piece to a jue with a similar format of inscription beneath the handle reading shi fu gui, which may be read as a dedication to 'Father Gui', preceded by the character shi for 'scribe', sold at Christie's London, 10 November 2015, lot 18.

The prominent spout, whorl capped posts, flared tail and long tripod legs make the jue one of the more striking vessels of the Shang dynasty ritual bronze assembly. The current jue showcases the highest mastery of ancient bronze casting technology, in a unique amalgamation of aesthetic ornamentation and ritualistic function. Used by Shang Kings in wine ceremonies linking them with the ancestral spirits, the unique silhouette of the jue wholly befits this original ritual use, and consequently became a marker of status when interred as a burial good in the graves of nobility.

As one of the oldest vessel forms, jue were used and continually adapted over several centuries, enjoying a relatively long period of popularity. In the earliest forms of Chinese writing, the character for jue in oracle bone inscriptions depict the long legs, spout and upright posts of the two present jue, suggesting a distinct vessel form and function from very early on (as discussed by E. Childs-Johnson in The Jue and its Ceremonial Use in the Ancestor Cult of China, Artibus Asiae, vol. 48, No. 3/4, 1987).

Smaller flat-bottomed pottery jue preceded the development of bronze forms, emerging during the Late Neolithic at sites such as Beiyinyangying, Jiangsu. (Zhongguo Kexueyuan Kaogu yanjiusuo, Xin Zhongguo Kaogu de Shouhuo, Beijing, 1962). The earliest primitive bronze jue date from the pre-Shang Erlitou period, with thin short legs, a dainty narrow spout and bulbous ‘waist’ to the body, with these design features continuing into early Shang (see the Panlongcheng Shang Dynasty Erligang period Bronzes in Hubei Provincial Museum, Panlongcheng Shangdai Erligang qingtongqi, Wenwu 1976.2; pp.26-43, picture no. 5). Over time, certain features became more pronounced, with longer legs and taller rim posts, perhaps to better fulfil its role during libation rituals. The exact way in which jue were used, leading to such a distinctive silhouette has been a point of continued scholarly discussion.

A corpus of over twenty different types of wine vessel in use during the Shang period attests to the importance of these libation ceremonies conducted by the rulers. Ritual preparation and drinking of wine would link the kings to the spirits of their ancestors, and symbolise both their power and legitimacy to rule with the mandate of Heaven.

The traditional ascription of the jue as a libation cup is somewhat problematic, with scholars early on recognising the curious rim posts and long spout would do more to impede drinking than to aid it. The eminent Li Ji, one of the ‘fore-fathers’ of Chinese archaeology, based his research on excavated jue from the Shang ruins at Yinxu, concluding the jue was designed for pouring wine, perhaps from a large storage jar in to a smaller vessel for drinking, and was used in tandem with flared vessels, gu (Li Ji, Studies of the Bronze Jue Cup, Nangang, Taiwan, Archaeologia Sinica, 1966, n.s 2). However, the long legs and peculiar capped posts at the rim hint at a yet more specific use. Current scholarly opinion suggests that the splayed legs of the jue allow for stable positioning over hot coals in order to heat the wine during libation rituals. The two upright posts at the rim may have been used in tandem with the long tail when tipping the hot vessel for pouring wine using “their overhanging caps, which could be caught and pulled up by leather thongs”, (Childs-Johnson, ibid, p.174).

The present jue represents typical late-Shang form, with a deep U-shaped spout, long tail and round-bottomed body. With the progression of time, the vertical posts became taller, placed further back from the spout along the rim.

Lot 157. A bronze halberd blade, Ge, Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 10 ½ in. (26.7 cm.) long. Estimate: GBP 6,000-GBP 8,000 (7,920 - USD 10,560). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017

The curved butt is crisply cast on each side with a stylised scroll design, and the nei is pierced with a single hafting hole. The tapered blade is heavily encrusted.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 19 October 1965, lot 38.

Sotheby's London, 14 November 1972, lot 224.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: See a ge-halberd blade with similarly shaped and decorated butt from the Harris Collection of important early Chinese art, sold at Christie's New York, 16 March 2017, lot 809.

Cf. my post: A bronze Ge-halberd blade, Late Shang Dynasty, 12th-11th Century BC

Another example is in the Museum van Aziatische Kunst, Amsterdam, illustrated by C. Deydier, Les Bronzes Chinois, Paris, 1980, p. 231, no. 99.

Lot 158. A bronze ritual wine vessel, gu, Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 10¾ in (27.4 cm) high. Estimate: GBP 20,000 - GBP 40,000 (USD 26,400 - USD 52,800). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The slender vessel is cast to the mid-section and lower body with taotiemasks on a dense leiwen ground, separated by scored vertical flanges. The upper section is decorated with four stylised cicada blades rising upwards towards the flaring neck. The surface is of a pale greyish-green tone with milky-green malachite encrustations.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 8-9 July 1974, lot 3.

Sotheby's London, 8 July 1975, lot 10.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 159. A bronze chariot shaft, Western Zhou dynasty (11th-10th century BC). 5 ½ in. (14 cm.) wide. Estimate: GBP 4,000 - GBP 6,000 (USD 5,280 - USD 7,920). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The fitting is cast with a central taotie mask and stylised scrolls. The surface has a dark brownish-black patina with mottled malachite encrustations.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 15 July 1980, lot 186.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: Compare the current lot to a chariot fitting of similar form and decoration, also dated to the late 11th-early 10th century BC, illustrated by William Watson in Ancient Chinese Bronzes, London, 1977, pl. 34b.

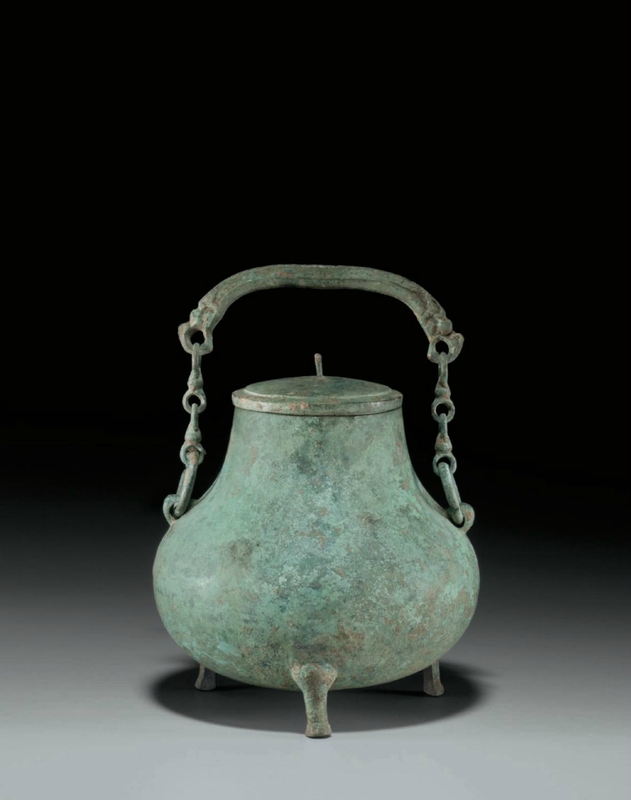

Lot 160. A bronze ritual wine vessel and cover, you, Late Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 13 in (33 cm) high. Estimate 80,000 - GBP 120,000 (USD 105,600 - USD 158,400). Price realised 248,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

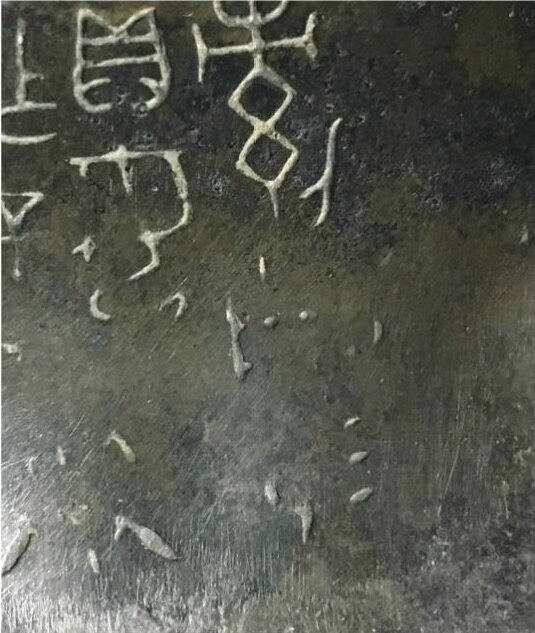

The vessel is cast to each side with a large taotie mask. The shoulder and foot are decorated with bands of stylised kuidragons, with a central animal mask to the lower shoulder. Each side is applied with a loop for attachment to the later swing handle. There is a single graph to the interior of the base and cover.

Provenance: The Collection of Mr Carl Morse.

Sotheby’s London, 14 November 1972, lot 227.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Literature: Wang Tao and Liu Yu, A Selection of Early Chinese Bronzes with Inscriptions from Sotheby’s and Christie’s Sales, Shanghai, 2007, no. 115.

Note: The stout oval-bodied you, an important wine vessel for religious rituals in the late Shang Dynasty, did not appear until the first century of the Anyang period (1300-1028 BC). The sophisticated decorative style found on the current vessel, with its captivating taotie masks and its well-proportioned shape, place it in the mid to late Anyang period. This particular vessel is notable for the single-graph inscription to the base, referring to a clan name.

A number of examples of similar form to the current vessel, but with flanges and leiwen ground are known. See a slightly smaller you of comparable proportions to the current lot in the Sackler Collection, illustrated by R. Bagley in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Washington D. C., 1987, p. 372, no. 64. Another you of similar size and form also dating to the Late Shang dynasty was sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 29 May 2013, lot 2172.

An important and very rare archaic bronze wine vessel, you, Late Shang dynasty, 12th-11th century BC, from the Idemitsu Museum, Tokyo. 12 3/4 in. (32.3 cm.) high. Sold for 37,950,000 HKD at Christie’s Hong Kong, 29 May 2013, lot 2172. © Christie's Images Ltd 2013.

Lot 161. A bronze harness jingle, Zhou dynasty (8th-5th century BC). 6 3/8 in. (16.3 cm.) high. Estimate 4,000 - GBP 6,000 (USD 5,280 - USD 7,920). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The jingle is cast to the front as a circular open flower, with an aperture to both sides, all supported on a spreading rectangular foot. The surface has a greyish-green patina with some malachite and russet-tone encrustations.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 3 October 1978, lot 29.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 162. A bronze axe head, Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 6 ¾ in. (17.2 cm.) long. Estimate 4,000 - GBP 6,000 (USD 5,280 - USD 7,920). Price realised GBP 6,875. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The top section of the blade and the shaft are cast on either side with a stylised animal mask. The greyish-green surface is encrusted with malachite.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 6 April 1976, lot 7.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 163. A bronze bell, yongzhong, Western Zhou dynasty (1100-771 BC). 12 in. (30.5 cm.) high. Estimate: GBP 3,000 - GBP 5,000 (USD 3,960 - USD 6,600). Price realised GBP 4,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The bell is cast to either side with three rows of protruding bosses, divided by rope-twist lines. There is a later-added inscription to one side, opposite a single animal-form graph. The bronze has a dark greyish-black patina with malachite and pale russet-coloured encrustations.

Provenance: 10 December 1979, lot 201.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: Bells of this type were made in graduated sizes to form a set or instrumental 'chime'. Each bell was capable of emitting two different tones, dependent on the exact location struck. R. Bagley explains "sets of bells were both aurally and visually the most prominent instruments of musical ensembles" in ancient China, but outside of China were unknown, (Music in the Age of Confucius, J. So (ed.), Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington DC, 2000, pp.35-63.)

Lot 164. A bronze ritual wine vessel, zun, Early Western Zhou dynasty (12th century BC). 10¾ in (27.4 cm) high. Estimate GBP 30,000 - GBP 50,000 (USD 39,600 - USD 66,000). Price realised GBP 224,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The vessel is boldly cast to the bulbous mid-section and lower body with taotie masks interspersed with vertical flanges. There is a later-added inscription to the underside of the foot. The surface is greyish-black in tone, with some areas of malachite encrustation.

Provenance: Christie's London, 9 July, 1979, lot 259.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: The result of Oxford thermoluminescence test no. 266j36 is consistent with the dating of this lot.

Lot 165. A gilt-bronze 'Chilong' belt, Warring States period (475-221 BC). 5 7/8 in. (15 cm.) long. Estimate GBP 6,000 - GBP 10,000 (USD 7,920 - USD 13,200). Price realised GBP 11,250. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The circular body of the belt hook is cast with an intricate network of eight chilong encircling a central medallion, all below the tapering shaft, which terminates in a curled dragon-head hook. There is a circular attachment to the reverse of the body.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 21 March 1978, lot 177.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 166. A fine and rare parcel gilt-copper lobed pouring bowl, yi , Tang dynasty (618-907). 8 7/8 in. (22.6 cm.) wide. Estimate GBP 60,000 - GBP 80,000 (USD 79,200 - USD 105,600). Price realised GBP 118,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The circular body of the belt hook is cast with an intricate network of eight chilong encircling a central medallion, all below the tapering shaft, which terminates in a curled dragon-head hook. There is a circular attachment to the reverse of the body.

Provenance: The Frederick M. Mayer Collection

Christie's London, 24 and 25 June 1974, lot 168.

Sotheby’s London, 3 April 1979, lot 43

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Literature: Gyllensvard, Bo, Tang Gold and Silver, B.M.F.E.A Stockholm, no. 29, 1957, line drawing fig. 42h and detail fig. 96 q.

Exhibited: T'ang, China House, New York, 1953.

Los Angeles County Museum, The Arts of the Tang Dynasty, 1957, catalogue no. 355.

The Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery, British Museum, London, October 2013 - May 2017.

A RARE TANG DYNASTY COPPER SPOUTED BOWL WITH PARCEL-GILT DECORATION

Rosemary Scott, Senior International Academic Consultant, Asian Art

This form is known as an yi ?, and is a pouring vessel which has its origins in bronze vessels of the Zhou dynasty, when yi were usually made with a handle opposite a wider mouth, and standing on slim legs. These Zhou dynasty bronze yi are believed to be have been used for pouring water to wash the hands before performing rituals. By the Western Han dynasty some yi vessels were manufactured in silver, occasionally with gold decoration, and were made without handle or legs. Such a Han dynasty yi vessel was excavated in 1957 at Baoji ? ? in Shaanxi province (illustrated in Charm and Brilliance – An Appraisal of the National Treasures in the Shaanxi History Museum – The Gold and Silver Wares, Xi’an, 2006, p. 142, no. 74). The shape evolved on metal wares of the Tang dynasty to a vessel which stood on a flared foot and had a more bowl-shaped body, which could be circular or petal-lobed – like the current example. These vessels are, however extremely rare either in silver or in copper, and the fact that the few extant examples are usually decorated with gold confirms their status as precious items.

A Tang dynasty silver five-lobed spouted bowl, standing on a high flared foot, with parcel-gilt decoration, was excavated at Lin’anxian , Zhejiang province from a tomb belonging to the Qiu ?family (illustrated in Tang dai jin yin qi, Beijing, 1985, no. 274). Another Tang silver spouted bowl, without lobes, but standing on a flared foot and decorated with parcel-gilt, was excavated in 1970 at Hejia village ???, Xi’an, Shaanxi province. A Tang dynasty copper spouted bowl with silver and gold decoration from the collection of Pierre Uldry was exhibited at the Rietberg Museum, Zurich, in Chinesishes Gold und Silber, Zurich, 1994, p. 162, no. 149. It is rare to find Tang dynasty vessels with parcel-gilt on copper. However, a fine copper lobed oval dish with flattened rim was excavated near Xi’an in 1968 and was included in the National Palace Museum exhibition World of the Heavenly Khan – Treasures of the Tang Dynasty, Taipei, 2002, p. 60. The repoussé band of scrolling flowers around the rim of the dish, and the chased design of a scholar playing a qin accompanied by a servant and a crane on the interior base, are both highlighted with parcel-gilt.

The gilding of metal appeared in China as early as the Shang dynasty. The technique employed by the Shang craftsmen is known as baojin, in which a thin sheet of hammered gold foil was applied to another metal, usually bronze. In preparation for the application of the gold foil, the surface of the metal to which it was going to be applied was roughened in order to give better purchase to the gold foil when it was hammered into place. In the Warring States period of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, however, another gilding technique was developed. This was mercury-amalgam gilding, known as gongji liujin or simply liiujin, in which gold was dissolved in mercury and the resulting mercury and gold paste was applied to the metal surface. It was then heated, so that the mercury was burned off, and the resulting thin gold layer on the surface was burnished to achieve a brilliant shine.

By the late Eastern Zhou period gold, like jade, had begun to be associated with immortality. The mercury-amalgam gilding technique, sometimes also known as fire-gilding appears to have been developed as a result Daoist alchemy associated with the search for immortality and the desire create man-made gold. By the beginning of the Han dynasty mercury-amalgam gilding was more commonly used than gold foil. In the Tang dynasty both the application of gold, and indeed silver, foil, and mercury-amalgam gilding were used to highlight certain parts of the design on vessels and personal ornaments such as hair pins. This gilding of certain areas, sometimes called parcel-gilding, produced colour contrast as well as adding a sumptuous brilliance to the designs on silver, bronze and copper. The Tang dynasty was a period in which richness of surface was appreciated in many media, and gilded metal work may be compared to luxurious silk brocades with designs woven in gold, or embroidered silk satins with couched gold and silver decoration.

The choice of floral sprays and butterflies as the theme for gilt decoration on the walls of the current bowl is characteristic of that seen on fine parcel-gilt metal wares of the high Tang period. A number of similar sprays are illustrated by Bo Gyllensvärd in ‘T’ang gold and Silver’, Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, No. 29, Stockholm, 1957, fig. 96, while the same author illustrated a variety of butterflies in fig. 62. Gyllensvärd also illustrated examples of the alternating truncated three-petal motif which appears at the top and bottom of the main band on the interior wall of the current vessel in fig. 79 of the same article. The current spouted bowl is also illustrated as a line drawing by Gyllensvärd in this article, fig. 42h, and part of its floral decoration is included in fig. 96q.

The creature depicted in the central roundel of the current spouted bowl appears to be a makara, represented as a winged dragon-fish. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, there has been considerable scholarly debate relating to the identification of the dragon-fish and the makara. Estell Nikles van Osselt suggested a clarification of the terminology in her paper "Song Ceramics: A Study of Makara and Dragon-fish Designs", in S. Pierson (ed.), Song Ceramics - Art History, Archaeology and Technology, Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia No. 22, London, 2004, pp. 119-50. While the Chinese dragon-fish is often, but not exclusively, linked to the notion of a fish in the process of turning into a dragon, the makara appears to be a mythical beast of Indian origin made up of elements from creatures such as crocodile, elephant and fish. The Chinese notion of a dragon-fish can, however, be found in early Chinese literature. Its appearance with the dragon-like head, paired with wings, echoes the yinglong, a form of winged dragon mentioned in the Shanhai Jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas). A related creature also appears in the 5th century Hou Han Shu (History of the Later Han).

The Indian makara appears in Indian temple architecture and on the jewellery worn by Vishnu, the god of Mercy. While the Goddess of the River Ganga is often depicted riding on a makara. The iconography of the Indian makara appears to have entered China around the same time as Buddhism was becoming established, but does not seem to occur in the decorative arts repertory until the Tang dynasty. Even in this early period, however, the auspicious nature of the Chinese makara is established by its association with the flaming pearl, as on the current spouted bowl. On the Chinese decorative arts the pearl is either shown being chased by two circling makaras, as on the interior of a 10th century Yue ware bowl in the collection of the Percival David Collection, illustrated by Rosemary Scott in "Miseyao and the Changing Status of Ceramics in the Tang Period", Wang Qingzheng (ed.), Yue Ware - Miseci Porcelain, Shanghai, 1996, fig. 15, or, alternatively, the pearl is depicted as being held in the mouth of the makara, as in the case of the current vessel.

According to Buddhist legend, the makara was originally a whale that saved the lives of five hundred drowning merchants at sea, and then sacrificed itself by providing its own body for food to feed the victims. Because of its compassion and sacrifice, both important virtues in Buddhist philosophy, the whale was then immortalised and transformed into a makara, characterised by the head of a dragon, the body of a whale with wings and a pearl by its side. It is also associated with prosperity, as the makara, in its whale-like manifestation was believed to be able to swallow anything, no matter how large. A makara with similar head to the one on the interior of the current bowl can be found chased in the centre of a Tang dynasty gold cup, excavated in 1983 in Xi'an, Shaanxi province, and now in the Shaanxi History Museum (illustrated by C. Michaelson, Gilded Dragons, London, 1999, pp. 98-9, no. 59), while a similarly coiled makara with flaming pearl is illustrated by Bo Gyllensvärd in ‘T’ang gold and Silver’, Butlletim of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, No. 29, Stockholm, 1957, Fig. 56b.

These Tang dynasty metal spouted bowls, which stand on a flared foot, pre-date the better known ceramic spouted bowls with flat base and a small ring handle below the spout which occur in the Jin and Yuan dynasties. A Jun ware spouted bowl of this latter type was excavated in 1977 from a Jin dynasty context at Yingxian, Shanxi province (illustrated in Complete Collection of Ceramics Art Unearthed in China, vol. 5, Shanxi, Beijing, 2008, no. 98). A Yuan dynasty blue-glazed example with flat base and small handle and gilt decoration was excavated in 1964 from a hoard at Yonghua South Road, Baoding, Hebei province (illustrated in Complete Collection of Ceramics Art Unearthed in China, vol. 3 Hebei, Beijing, 2008, no. 225).

This gilded copper bowl is an example of a rare vessel form, in an unusual material, decorated in a sumptuous technique, and in a style typical of the rich decorative traditions of the Tang dynasty.

Lot 167. A bronze knife, Warring States Period (475-221 BC). 9 in. (22.8 cm.) long. Estimate GBP 3,000 - GBP 5,000 (USD 3,960 - USD 6,600). Price realised GBP 3,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The knife is cast with a slender gently curved blade, sharpened on one edge and tapering at the point. The haft is decorated with a stylised scroll motif, terminating with a pierced rectangular handle. The surface has areas of rich green malachite encrustation.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 15 July 1980, lot 179.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 168. A bronze ritual blade, Shang dynasty 1600-1100 BC). 9 7/8 in. (25.1 cm.) long. Estimate GBP 2,000 - GBP 3,000 (USD 2,640 - USD 3,960). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The knife is cast with a gently tapered blade and a kidney-shaped ring handle. The surface has a pale green patina with malachite encrustation throughout.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 3 April 1979, lot 41.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 169. A bronze oval ritual vessel, xu, Spring and Autumn period (6th century BC). 7 ¾ in. (19.7 cm.) wide. Estimate GBP 4,000 - GBP 6,000 (USD 5,280 - USD 7,920). Price realised GBP 5,250. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The vessel is supported on four cabriole feet cast with delicate animal masks and is applied with two buffalo-head loop handles to the sides. The bronze surface is encrusted with mottled malachite, azure and russet tones.

Provenance: Acquired in London prior to 1986.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 170. A bronze openwork brazier, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 9 ½ in. (24.1 cm.) long. Estimate GBP 4,000 - GBP 6,000 (USD 5,280 - USD 7,920). Price realised GBP 9,375. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The upper, oval section has openwork sides cast with the animals of the Four Directions, and has four tab supports that rise from the rim. The lower section, which is of tapering rectangular shape, is raised on four crouching human supports, and has an openwork grate to the base. A flattened handle at one end curves up to a leaf-shaped terminal.

Provenance: Christie's London, 5-6 July, 1983, lot 108.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: Similar braziers are illustrated in Ancient Chinese Arts in the Idemitsu Collection, Tokyo, 1961, pl. 209; and in Chinese Bronzes from the Buckingham Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1946, pls. LXV, LXVI and LXVII. These examples retain the ear cup that would have rested on the supports at the rim, and also the tray on which the brazier would have stood. A brazier of this type was sold at Christie's New York, 13-14 September 2012, lot 1252.

A small bronze openwork brazier, Eastern Han dynasty (AD 25-220). 9 in. (23 cm.) long. Sold for 11,875 USD at Christie's New York, 13-14 September 2012, lot 1252. © Christie's Images Ltd 2012.

Lot 171. A bronze tripod wine vessel and cover, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 6 1/8 in. (15.6 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 1,500 - GBP 2,500 (USD 1,980 - USD 3,300). Price realised GBP 2,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The vessel is supported on three short cabriole feet and is applied to the upper body with a pair of loop fittings linked to a chain handle. The surface is heavily encrusted with areas of malachite and azurite.

Provenance: Acquired in London prior to 1986.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: Compare the current vessel to a very similar hu-form wine vessel and cover, with comparable chain handle, sold at Christie's New York, 14-15 September 2017, lot 910.

A bronze tripod wine vessel and cover, hu, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 8½ in. (21.5 cm.) high with handle. Sold for 16,250 USD at Christie's New York, 14-15 September 2017, lot 910. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

Lot 172. A small bronze vase and cover, fanghu, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 7 in. (17.8 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 3,000 - GBP 5,000 (USD 3,960 - USD 6,600). Price realised GBP 8,125. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The square-form vase is applied to either side of the body with a stylised animal mask-handle with a loose ring. The cover is cast with a further loop and ring handle.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 25 March 1975, lot 160.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 173. A bronze ritual tripod food vessel and a cover, gui, Western Zhou dynasty (1100-771 BC). 13¾ in (34.9 cm) wide. Estimate GBP 50,000 - GBP 80,000 (USD 66,000 - USD 105,600). Price realised GBP 50,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

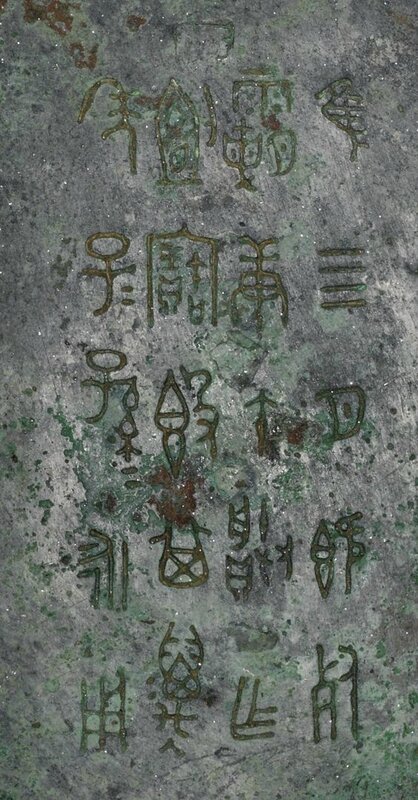

The body is cast with horizontal grooves between a band of stylised scrolls to the rim and foot and is applied with two animal-head C-form handles. The vessel is supported on three claw-form feet with animal heads to the top. The matched cover is decorated with a further band of archaistic scrolls. There is an inscription to the interior base of the vessel and a later-added inscription to the interior of the cover.

Provenance: Acquired in London prior to 1986.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: The inscription to the interior of the base can be read 'in the gengyindate of the fourth month during the jisipo moon phase (the fourth quarter), Zhen made Yi this precious gui vessel. May his sons and grandsons use it for ten thousand years.'

Compare the current vessel to a gui of similar form, supported on three feet and with comparable horizontal grooves characteristic of the late Western Zhou dynasty, illustrated by Jessica Rawson in Western Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, vol. IIB, p. 446, no. 57.

Lot 174. A bronze tripod vessel, ding, Warring States Period (475-221 BC). 13 5/8 in. (34.6 cm.) wide. Estimate GBP 10,000 - GBP 20,000 (USD 13,200 - USD 26,400). Price realised GBP 13,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The deep, globular body is raised on three cabriole legs and has two upright handles decorated with bands of angular scrolls. The sides are cast with two bands of angular tightly arranged interlocking dragon scrolls. The domed cover is decorated with related bands, separated by three ring handles. The surface is mottled with azurite and malachite encrustations.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 23 May 1972, lot 5.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: See a similar vessel and cover, also dating to the Warring States period which sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 31 May 2010, lot 2072.

A large archaic bronze ritual food vessel and cover, ding, Warring States Period, 5th century BC. 14 11/16 in. (37.2 cm.) high. Sold for 1,220,000 HKD at Christie's Hong Kong, 31 May 2010, lot 2072. © Christie's Images Ltd 2010.

Lot 175. A bronze ritual vessel, gu, Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 10 ¼ in. (26 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 8,000 - GBP 12,000 (USD 10,480 - USD 15,720). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The vessel is cast to the mid-section and lower body with taotie masks on a dense leiwen ground, below the undecorated flaring neck. The surface is of a brownish-grey tone with areas of malachite encrustation.

Provenance: The N. S. Brown Collection.

Sotheby's London, 13 March 1942, lot 55.

Sotheby's London, 15 July 1980, lot 193.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 176. A bronze ritual food vessel, gui, Early Western Zhou Dynasty (11th-10th century). 9 ¼ in. (23.5 cm.) diam. Estimate GBP 40,000 - GBP 60,000 (USD 52,400 - USD 78,600). Price realised GBP 43,750.© Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The sides are cast with vertical ribbing between an upper band oftaotie on a leiwen ground, centred on each side by a high-relief animal mask, and a band of taotie dragons above the foot. The loop handles have horned feline masks and terminate in a vertical tab cast with stylized scrolls. There are areas of malachite encrustation to the dark greyish-green surface.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 18 December 1967, lot 103.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 177. A bronze ritual food vessel, fu, Spring and Autumn period (6th century BC). 14 in. (35.5 cm.) wide. Estimate GBP 3,000 - GBP 5,000 (USD 3,930 - USD 6,550). Price realised GBP 3,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The vessel is cast to the side and base with a dense network of interlocking scrolls, below a band of stylised geometric scrolls to the rim. The sides are applied with a pair of animal-head loop handles. There are areas of malachite and azurite encrustations to the surface.

Provenance: Christie's London, 11 July 1977, lot 170.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 178. A bronze tripod vessel, ding, Warring States Period (475-221 BC). 8 in. (20.3 cm.) wide. Estimate GBP 10,000 - GBP 20,000 (USD 13,200 - USD 26,400). Price realised GBP 68,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The vessel is raised on three cabriole feet, decorated with animal heads and is applied to the body with a pair of small loop handles. The cover is surmounted by a flared openwork crown finial formed by a network of interlocking serpents, surrounded by four loop fittings. The surface has a mottled greyish-green patina with areas of russet-coloured and azurite encrustation.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 10 July 1979, lot 6.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: Compare the current piece to a rare bronze elliptical vessel and cover, xu, with similar flared openwork crown finial to the top of the cover, sold at Christie's London, 10 November 2015, lot 22.

A rare bronze elliptical vessel, xu, Early Western Zhou, Spring and Autumn period (6th century BC). 8.6/8 in. (22 cm.) diam. across the handles. Sold for 43,750 GBP at Christie's London, 10 November 2015, lot 22. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

Lot 179. A bronze tripod vessel, ding, Late Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BC). 7 1/8 in. (18.2 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 10,000 - GBP 20,000 (USD 13,200 - USD 26,400). Price realised GBP 68,750. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The exterior of the vessel is decorated with three taotie masks above each foot, reserved on a dense leiwen ground, with two upright loop handles rising from the rim. The bronze has a mottled dark grey patina with some areas of encrustation.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 30 March 1978, lot 17.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 180. A gilt bronze mask and ring handle, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 4 ½ in. (11.5 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 3,000 - GBP 5,000 (USD 3,960 - USD 6,600). Price realised GBP 4,375. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The mask is cast as a taotie with bulging eyes, with the snout formed as a loop supporting a large ring. The reverse is applied with a rectangular tab for attachment. There are areas of malachite encrustation to the surface.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 13 December 1983, lot 29.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 181. A green-glazed pottery 'Hill' censer, boshanlu, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 9 in. (22.8 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 2,000 - GBP 3,000 (USD 2,640 - USD 3,960). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The censer is raised on a stem foot rising from a dish and the conical pierced cover is modelled in the form of overlapping mountains, surmounted by a crouching figure. It is covered in a pale green glaze suffused with fine crackles.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 13 December 1977, lot 289.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 182. A bronze 'Hill' censer, boshanlu, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 8 ¾ in. (22.2 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 6,000 - GBP 10,000 (USD 7,920 - USD 13,200). Price realised GBP 7,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The censer is raised on a tall splayed foot which is decorated with a band of stylised scrolls, all upon a circular drip plate. The cover is cast in openwork as overlapping peaks. The surface has a pale greyish-green patina with russet, blue and green encrustation.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 3 October 1978, lot 38.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: The cover of this hill censer depicts the mystical overlapping peaks of Mount Peng, regarded in Han dynasty Daoist tradition as a paradise realm for the spirits of immortals. Perhaps due to the popularity of this motif, there are several comparable Han dynasty censers; see the British Museum collection hill censer, (Museum no. 1936,1118.52) of similar simple stem-goblet form. Another example was sold at Christie's London, 10 November 2015, lot 3. For an extensive discussion on the history and symbolism of the 'hill' censer, see Jessica Rawson, 'The Chinese Hill Censer, boshan lu : A Note on Origins, Influences and Meanings', Art Asiatiques, 2006, Vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 75-86.

Censer (hill. with lid), boshanlu. Bronze. Han dynasty (206BC-220), Museum no. 1936,1118.52 © The Trustees of the British Museum.

A bronze 'Hill' censer, boshanlu, Han dynasty (3rd century BC-3rd century AD). 9 5/16 in. (23.8 cm.) high. Sold for 30,000 GBP at Christie's London, 10 November 2015, lot 3. © Christie's Images Ltd 2015.

Lot 183. A pottery figure of an attendant, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 16 in. (40.6 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 4,000 - GBP 6,000 (USD 5,280 - USD 7,920). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The figure is depicted standing, dressed in long robes which flare at the base, with her hands joined at her front.

Provenance: Sotheby's London, 25 March 1975, lot 209.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 184. A polychrome-decorated pottery figure of a standing official, Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). 13 5/8 in. (34.6 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 2,000 - GBP 3,000 (USD 2,640 - USD 3,960). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

The figure is depicted standing with his hands clasped to his chest, dressed in red robes and his breast plate outlined in black. His fierce facial expression is delicately picked out and he wears a ruyi-form hat on his head.

Provenance: Acquired in London prior to 1986.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Lot 185. Two painted pottery figures of heavenly spririts, Tang dynasty (618-907). The largest, 19 1/8 in. (48.6 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 10,000 - GBP 15,000 (USD 13,200 - USD 19,800). Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2017.

One figure is depicted with a pair of long horns, its right arm raised, ready to strike a snake coiled around its left leg. The other figure is shown seated on its haunches, with large winged ears and a long spiralling horn protruding from the top of its head. Both figures are covered in white slip, with traces of red and black pigment.

Provenance: The figure with the spiralling horn: Sotheby's London, 5 July 1977, lot 86.

The other figure: Sotheby's London, 30 March 1978, lot 99.

The Michael Michaels Collection of Early Chinese Art.

Note: Fantastic animal guardian figures, known as zhenmushou (demon-quelling beasts) were included in tombs in order to ward off evil spirits. These are first found in the Northern Wei Dynasty (386 - 534 AD) and continued during the Tang Dynasty. These figures took the form of hybrid creatures, sometimes with human elements. Such figures are occasionally depicted with snakes, as on one of the current figures. Comparable figures can be seen, such as the pair of large tomb guardians in the Princeton University Museum of Art, inv. 2001-215.1-.2); and another exhibited at The Bowers Museum of Cultural Art, Santa Ana, California, and later at The Taft Museum, Cinncinnati, Ohio, Seeking Immortality, Chinese Tomb Sculpture from the Schloss Collection, 1996-1997, catalogue no.151, fig. 42, p. 53. The latter also displays a slightly spiralling horn as in the second figure in this lot. Other figures of this type were found in Tang tombs at Xi'an, Shaanxi province (see Kaogu yu Wenwu, 1991, no. 4, fig. 17:2, p. 60.

Pair of tomb guardians: human-faced figure, Chinese, Tang dynasty, 618–907, ca. mid–8th century. Earthenware with silver, gold, and painted decoration. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund, 2001-215.1 a-b, 2001-215.2 a-b © 2017 The Trustees of Princeton University.

Christie's. Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art, 7 November 2017, London

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240411%2Fob_4a5248_2024-nyr-22642-0913-000-a-longquan-cel.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240410%2Fob_b0ef72_2024-nyr-22642-0908-000-a-carved-ding.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F29%2F47%2F119589%2F129819867_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F57%2F119589%2F129818552_o.jpg)