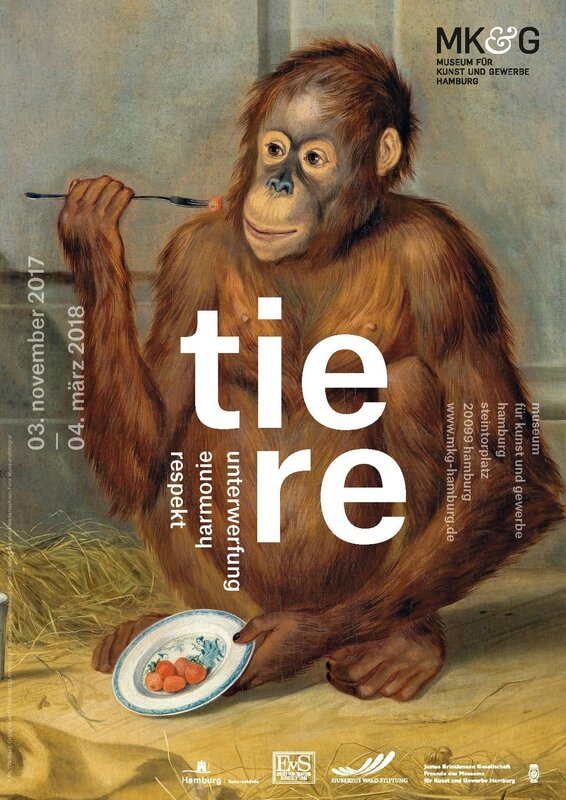

Animals: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg opens new exhibition

"Animals. Respect / Harmony / Submission". Poster.

HAMBURG.- Animals are a frequent subject of debate these days. Do they have a soul? How much do they suffer? Are we under any obligation to protect their individuality by granting them rights? Are human beings morally authorized to do as they want with animals, to consume them, rob them of their freedom and train them for the purposes of entertainment? Scientific discussion takes the relationship between animal and human being very seriously. In the everyday life of our consumption-oriented society, on the other hand, that relationship oscillates between unreflecting exploitation and sentimental anthropomorphization. Against the background of these contrasts, the exhibition ANIMALS at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburghas been geared primarily towards informing visitors and sensitizing them to ways and means of respectful co-existence. With a view to the visual and applied arts but also to science, the show undertakes to re-evaluate the common history of man and animal from the perspective of a wide range of epochs, cultures and media. Loans from museums as well as natural history and ethnology-oriented institutions of Germany and the world will enhance the objects from the MKG’s own abundant and diverse collection. The chief focus is on works of the visual arts in which the interaction between animal and man gives rise to something altogether new. So-called thematic islands unite creations of high culture with those from popular contexts, while also integrating examples from indigenous cultures and natural history. The exhibition features some 200 objects dating from antiquity to the present, including paintings, sculptures, prints, photographs, video art, large-scale installations and films. In addition to the 1,200 square metres exhibition there are 14 satellite locations throughout the entire museum that focus on animals. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue published by Hirmer Verlag.

This exhibition explores the relationship of animals and mankind with a view on the arts and focusses on ethical, spiritual and emotional questions. The centre for Natural History (CeNak) at the University of Hamburg, as a cooperation institution of the MKG, completes the perspective with a scientific view of mankind in the animal world. Beside the joint projects with the Zoological Museum, CeNak presents a special exhibition “Vanishing Legacys: The world as a Forest” (10 November 2017 – 29 March 2018) addressing the current research results regarding species extinction, deforestation and climate change.

Origins and Inspiration

The oldest known depictions of animals date to over 30,000 years ago – carved out of bones or painted on the walls of caves. Ever since humans started making artworks, animals have been one of the main sources of inspiration. The earliest object in the exhibition, the engaging amber sculpture of a moose from Weitsche, dates back to the Ice Age. Just like a falcon sculpture found in Egypt, a jade deer from China, a bull from the ancient Orient, and a golden boar from Greece, it bears witness to the encounter between human and animal. All of these works tell us something about how humans viewed the animals around them, how the particular society saw itself and about its religious and moral constitution, its attitude to creation and to nature. The exhibition examines how artists across the ages envisioned animals and the aesthetic developments that influenced their interpretations.

Sphinx, probably Roman copy after classical model (440-450 v. Chr.), Marble, 59,8 cm, Antikenmuseum Basel and collection Ludwig, Basel, © Antikenmuseum Basel and collection Ludwig

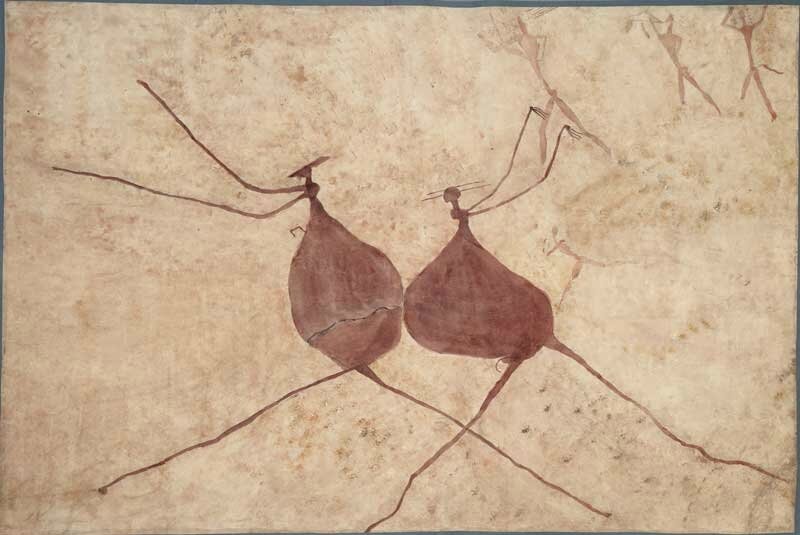

Maria Weyersberg, Praying mantises, Namibia, Groß-Spitzkopjes, 1929, watercolor on paper, 92 x 135 cm, collection Frobenius-Institut, Frankfurt am Main

Sirene, terracotta, 3rd century BC Athens, 14.6 x 12 cm, Inv. NI 5417, © Staatliche Antikensammlungen and Glyptothek Munich, Photo: Renate Kühling

Akihiro Higuchi, Collection Cockroach, 2017, Insects Preperat, Japanese Lacquer, Gold Dust, Powdered Silver, 13 x 6 cm, Courtesy of Mikiko Sato Gallery, Hamburg, © Mikiko Sato Gallery

Longing and Distance

Paradise! A return to Arcadia is not possible, but the arts can play a vital role on the way to a better future. The selection of works on view is not based on chronology or specific species; instead, two renderings of elephants form thematic bookends for a wide range of animal depictions ranging from early civilizations to the present. The cave was the birthplace of both magic and enlightenment, as our ancestors began to develop a first impression of themselves and the world. Humans did not yet dominate their world; on a painting in the Mutoko Cave in Zimbabwe, fleet stick figures seek their place in the vast animal kingdom. Two majestic elephant silhouettes stand watch over the scene teeming with flora and fauna. They are the rulers of the visible world and the mediators between it and transcendental spheres. The life-size copies made by art students in 1929 on an expedition to Zimbabwe with the ethnologist Leo Frobenius spread word of the prehistoric rock and cave paintings. The seven-meter-wide drawing of the Big Elephants and further sheets convey in the exhibition a connection between human and animal in prehistoric times, in a society whose organization we still know very little about. But they stand above all for modern man’s longing for a harmonious consensus with nature, a primordial state that we presume prevailed in many early civilizations.

Large Elephants, other Animals, and People Painted in Various Layers, after a wall painting in the Mutoko Caves in Zimbabwe, 1929, Joachim Lutz © Frobenius-Institut an der Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main

It is for this reason that Franz Marc’s Dog Lying in the Snow (1911) and The Goldfish (1925) by Paul Klee are juxtaposed with the cave paintings in the show. Both artists tried in their work to picture an authentic world that had in the meantime been lost. Klee’s Goldfish visualizes the beginnings of life emerging from the primordial soup of the waters. Marc’s metaphysical view of a resting animal at peace with itself and the world imagines an early state of innocence, which must then yield to the exigencies of civilization. Joseph Beuys, too, evoked melancholy at the loss of an edenic unity of man and animal. He sought closer contact with the animal spirit in ceremonial acts. Just as the “animalization” of the world represented for Marc a vision of the future, for Beuys, recovering the communication between human and animal was an integral part of a new, environmentally motivated social movement.

Franz Marc (1880-1916), Lying dog in the snow, 1910/1911, oil on canvas, 62.5 × 105 cm, Städel Museum, Frankfurt / Main, property of the Städelsche Museums-Verein eV, photo: © Städel Museum - ARTOTHEK

Paul Klee (1879-1940), The Goldfish, 1925, oil and watercolor on paper, 49.6 x 69.2 cm, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, © Hamburger Kunsthalle / Elke Walford

“Photographic Experiments Using X-Rays”, Two Goldfish, a Sea Fish and Sole, Josef Maria Eder (1855–1944) and Eduard Valenta, Vienna 1896 © Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

The collection of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), Box Containing Four Petrified Fish From Monte Bolca, Fossils in limestone from the Eocene age (Lutetium), © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

A contemporary response to the elephants from the cave is provided in a video installation by Douglas Gordon from 2003: The elephant cow Minnie was brought from the circus to New York’s Gagosian Gallery. We see her there laying down – or falling – and awkwardly getting up again in a clinical white room. In Play Dead; Real Time, Gordon doesn’t summon thoughts of a common origin but instead reflects on the changed balance of power in the course of thousands of years of co-evolution of humans and elephants. Forced to assume unusual poses for the camera, Minnie looks both powerful and vulnerable at the same time. In her clumsy movements, she lends a face to all the anonymous trapping, training, and exploitation of elephants perpetrated by so many humans. The impressive work combines admiration for the beauty and dignity of the animal with empathy for a subjugated and drilled creature, and finally grief over the dying out of an endangered species.

Douglas Gordon, Play Dead; Real Time (this way), Play Dead; Real Time (that way); Play Dead; Real Time (the other way), 2003, Video Still, MMK Museum of Modern Art, Frankfurt am Main, © Studio lost but found / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Insight and Appropriation

We can never really know what it feels like to be an animal, nor can we say with any certainty how an animal feels about us. The desire to understand animals is an ancient one. Insights have been sought using all conceivable means. Scientific developments in this field and innovations in technical media have also influenced artistic practice. Over the centuries, paintings and graphic art techniques have shaped our basic concepts about the animal world. In the Renaissance, animals were made the sole subjects of depictions. Durer’s Young Hare is still today an iconic animal image. A contemporary copy by Hans Hoffmann is on view in the exhibition. Dürer’s Rhinoceros, on the other hand, originally printed as a leaflet, brought an animal worldwide fame that normally lies outside our horizon of experience. The combination of the fantastical, factual, and direct observation is characteristic of bestiaries and zoological encyclopedias that map the myriad species of the animal kingdom; exotic and mythical beasts are rendered here just as realistically as domestic animals. The deceptively true-to-life images are not an end in themselves, however, but are above all testimonies to the skills of the artists who made them. In the mid-18th century, George Stubbs’s gaze penetrated right under the animal’s skin. In five layers, he dissected the body of a horse down to the bare skeleton. This knowledge-oriented deconstruction reveals not only the anatomical facts but also a fundamental realization: The horse, like the human, is a creature of flesh and blood, vulnerable and capable of feeling pain. In the 19th century, the new media of photography and film brought previously hidden phenomena to light, and X-rays laid bare the internal structure of animals. Etienne-Jules Marey’s chrono-photographic experiments captured motion sequences in slow motion, in order to find new answers to the ageold question: Why does a cat always fall on its paws?

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Rhinocerus, 1515, woodcut, 25.6 x 32.1 cm, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Kupferstichkabinett, © Hamburger Kunsthalle / Christoph Irrgang

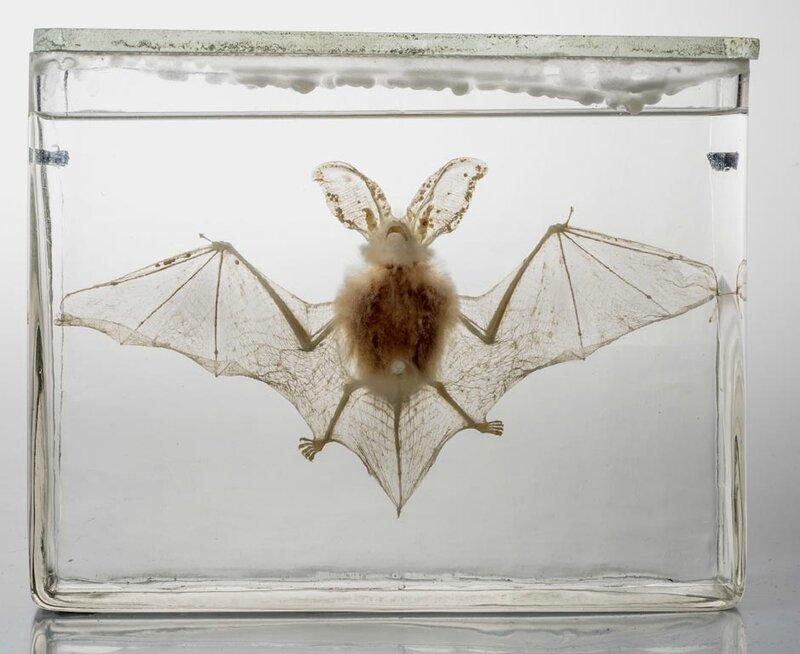

Animals can do many things humans can’t: They can rise into the air and maneuver safely through the dark night, like the bat. Bats sleep upside down while we are awake, and then unfurl their wings at dusk. A watercolor from the Dürer school depicts the bat’s flight apparatus in detail, the animal’s wingspan spreading beyond the margins of the sheet. Detailed anatomical studies were meant to make the “fantastic” world of animals understandable. Ernst Haeckel, for example, ventured in his 1904 Art Forms in Nature thirteen taxonomic descriptions of various bat faces. In the exhibition, a contemporary study of the bat’s abilities is contributed by Bat Bot from 2017. An American research team succeeded in mimicking the fascinating bat aeronautics, complete with complex movement sequences and a whisper-thin flight membrane.

Albrecht Dürer, formerly attributed, Bat, 1522 © Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon, Photo: Pierre Guenat

Brown long-eared (Plecotus auritus), whitening preparation, 15 x 20 x 6 cm. University of Hamburg, Center for Natural History, Zoological Museum, © Photo: MKG

Subjugation and Fascination

Do animals have a soul? Are we really entitled to eat them, imprison them, and drill them to do our bidding? In an image cosmos made up of 177 individual photographs made between 2006 and 2010 in various European food production locations, Michael Schmidt shows matter-of-factly, without sentiment or any moral appeal, the reality of the processing of animals for food. The very objectivity of this presentation of an everyday practice prompts us to critically reflect on the mass exploitation of animals. A rejoinder to the tableau Food is posed by an 18th-century Boar’s Head Tureen from the collection of MKG. In that era, hunting wild animals was still a dangerous feat, and their consumption not yet commonplace and hence associated with special ceremonies. While in the Middle Ages the bloody animal corpse would be placed directly on the table, the etiquette of the European courts banished the evisceration and cutting up of the animal to the kitchen. The deceptively realistic porcelain boar’s head contains not an identifiable animal but rather a steaming pot of game meat ragout.

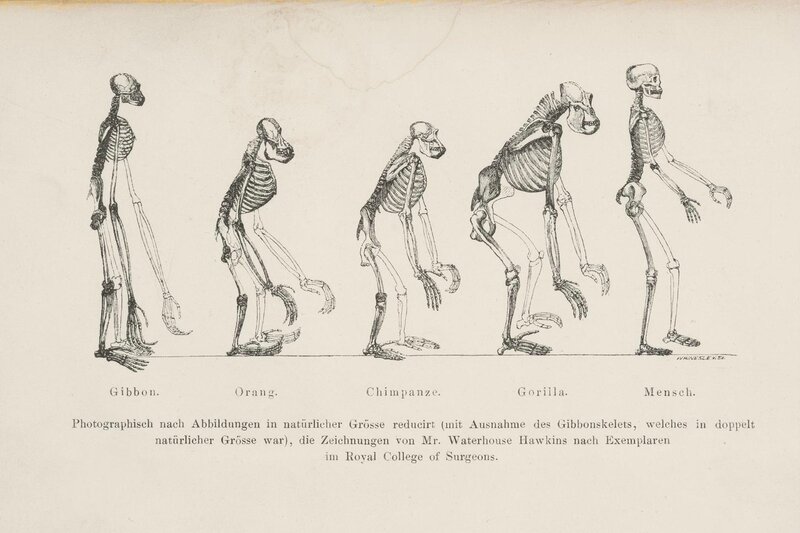

The young female orangutan that was brought to The Hague from the Dutch East Indies in 1776 caused a sensation. Speculations about the nature and appearance of the great apes and the boundaries between human and animal could finally be tested on a living specimen. The orangutan was clever, could break free of her chains, open a bottle of wine, take a swig, and then put it back. She was always in a good mood and didn’t like sleeping alone. On the first oil painting of a great ape, this orangutan eats strawberries from a porcelain plate with a silver fork. Despite these civilized traits, however, her abode is still a barren pen lined with straw. Human superiority is substantiated. Two generations later, Charles Darwin would characterize the ape as man’s closest relative, arguing for its ability to feel and empathize with others. Since then, humans have been forced to acknowledge that they are not the crowning achievement of all creation but merely one animal among others. Only recently there have been discussions in the USA and Turkey about banning Darwin’s theory of evolution from school curricula – demonstrating how disturbing this realization can still be even today.

Tethart Philipp Christian Haag, Orang Utan, eating strawberries, 1776, oil on canvas, 109 x 89 cm, Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ullrich-Museum, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen. © Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen, Braunschweig, Photo: Museum Photographer

Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature, Frontispiece, Thomas Henry Huxley, drawn by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, 1863, © Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg, Carl von Ossietzky

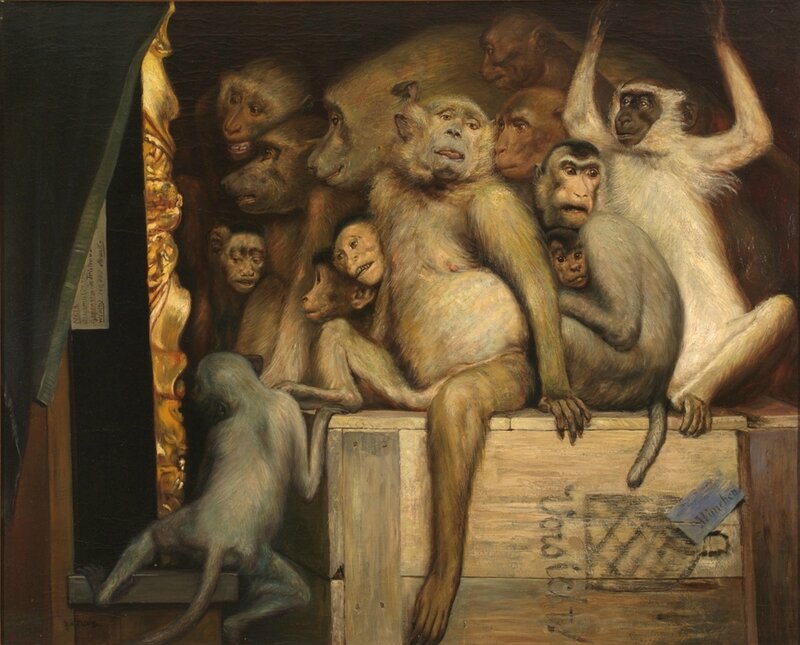

No animal has preoccupied man as much as the ape. This is evident from a variety of exhibits: For the Egyptians, the baboon was the incarnation of Thot, the god of wisdom. The medieval world view banished the apes to the kingdom of the devil. On the stage of the Baroque courts, the ape wore a wig and inspired laughter with his vain attempts as an artist. In the wake of Darwin’s theorizing about evolution, Gabriel von Max showed a rhesus monkey confronting the skeleton of a fellow ape in a painting from around 1900 – does the ape realize upon this sight its own mortality? As late as the 1920s, apes in the zoo were still being presented dressed in human clothing. The constellation of ape and woman became a hot topic in the 1930s with the movie hero King Kong, a subject of lasting fascination. The chilling realism of the monstrous giant ape and the breathtaking chase scenes and views of the beast scrambling up New York’s Empire State Building contrasted the savage beast with the contemporary ideal of the progress of civilization. In the bloody end, however, pity for the unrequited lover triumphs over the fear of untamed nature.

Statuette of the God Thot in the shape of a sitting baboon, Egypt, 3 rd c. BCE, © Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum, Hildesheim

Gabriel von Max, Monkeys as judges of art, around 1889, oil on canvas. Private collection © photo: Martin Hahn

Monkey Orchestra, Meißen, Otto Pilz, 1908–1912, Private collection

Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, King Kong and the White Woman, 1933, film still, © Photo: Beta Film / Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt-KINEOS Collection

Myth and Desire

Ancient mythology provided some disturbing answers to the question of where human nature ends and animality begins. From the constellation of god – human – animal, it developed hybrid creatures that challenge boundaries and taxonomies. How close or how far apart are human and animal? These composite creatures are unsettling because they make us sense that the boundaries are fluid ... Out of the countless anthropomorphic creatures that lie outside the accepted systems, the exhibition has chosen to focus on feathered changelings. The femme fatale decked out in feathers is dangerous! The Sphinx with her riddles about the world is featured on Sigmund Freud’s ex libris for good reason ... Medusa’s gaze can kill, no man alive can resist the song of the sirens, and vampires subsist on the blood of humans. As erotic temptresses, they make men their victims, arousing desire even today. Amidst ancient sculptures and paintings by Fernand Khnopff, Franz von Stuck, and Max Beckmann, the exhibition circuit also presents a modern-day siren: a bolero covered in parrot feathers from Jean Paul Gaultier’s first haute couture collection, in 1997, animated by a multimedia projection created at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg that lends the seductive feathered object a voice.

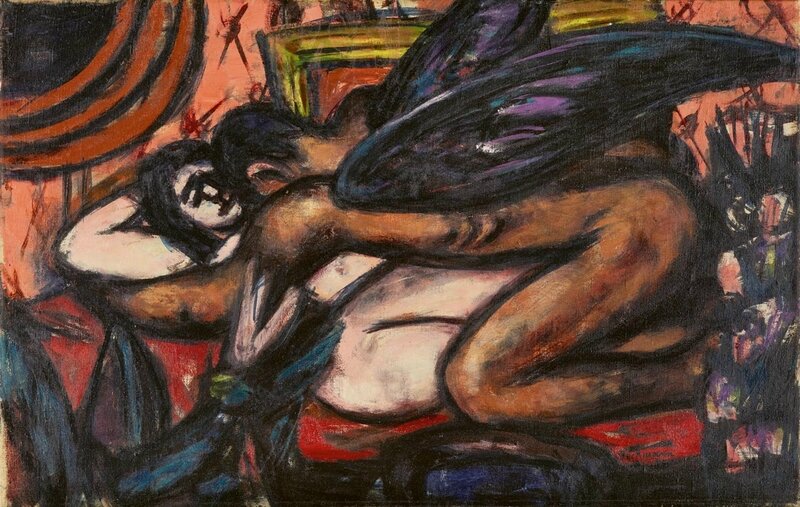

Max Beckmann (1884-1950), Vampire, 1947/48, oil on canvas, 53.2 x 82.6 cm, on permanent loan to the Museum Folkwang, Essen, privately owned since 2017, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, photo : Museum Folkwang Essen - ARTOTHEK

Humans do not appear physically in this exhibition; they are presented instead by way of their desires and fears as mirrored in the depiction of animals. After their physical bearings have been lost and their faculty of reason switched off, however, we do encounter humans in two memorable images: Francisco Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters from 1799 shows a man in an “exceptional state,” beset by owls and bats. The most famous scene of animals taking command is Johann Heinrich Füssli’s Nightmare, whose animal protagonists give rise to a wide range of interpretations: incest fantasy, the processing of unfulfilled passions, a moral panorama of the revolutionary age, or an encoded expression of violence. Because it lends itself to so many possible readings, the painting with its trio of white horse, apelike incubus, and woman’s body lasciviously draped upside-down across the bed has become an iconic image of the unfathomable relationship between human and animal. In the age of Enlightenment, animals insist in this picture on having a life of their own, which humans try to suppress and dominate without being able to fully comprehend it. When the dreamer awakes, her nighttime companions have vanished. This is why the physical weight of these chimeras so disturbs the subconscious mind. They point to the connection between animals and sexuality, an association already anchored in ancient mythology, which was taken up by Sigmund Freud and then appears in various forms in the erotic fantasies of the 20th century. Max Ernst painted the motif of the Bride of the Wind in 1927 as something he had seen in a dream, under the influence of psychoanalysis. Two amorphous horse bodies writhe in love play, under the sway of a magical star. The concept of the “uncanny” that Freud formulated in 1919, which acknowledges a feeling of strangeness, repulsion, and fear as part of what we find aesthetic, applies exceptionally well to the animals people encounter in their dreams.

Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825), The Nightmare, oil on canvas, © Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurt Goethe Museum, photo: David Hall

Reconciliation and Respect

The exhibition ends on a conciliatory note with the video installation Raptor’s Rapture by Allora & Calzadilla. A musician and an Old World vulture sit opposite one another, and aggressive tones fill the room. The music is played on a prehistoric flute, a replica of the oldest surviving musical instrument, which came to light in 2008 in the Hohle Fels Cave. It was carved 35,000 years ago from the wing bone of a griffon vulture, an ancestor of our protagonist. Through the music, the bird and woman symbolically come into contact with their ancestors. They communicate in this way, the vulture responding to the sound of the flute with guttural calls and spanning its powerful wings. “Kak, kak,” calls the flute just like the vulture, sounds from a distant world. If the ability to express oneself artistically is part of being human, then it was apparently the animal that triggered this creativity in the first place. The vulture contributed the material for the flute not only with its wing bone, also sending the impulse to create sound and conveying to humans a sense of musicality. Raptor’s Rapture shows human and animal wrapped up in a dialogue and thus awakens the longing for harmonious co-existence – a desire that is presumed to have prevailed in primitive society but which has now been lost and must be regained in order to confidently face a common future.

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, Raptor's Rapture, 2012, HD Video, 23:30 minutes, © Allora & Calzadilla; Courtesy of Allora and Calzadilla and Lisson Gallery

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, Raptor's Rapture, 2012, HD Video, 23:30 minutes, © Allora & Calzadilla; Courtesy of Allora and Calzadilla and Lisson Gallery

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F56%2F119589%2F129494680_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F04%2F81%2F119589%2F128791640_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F73%2F16%2F119589%2F128381257_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F03%2F119589%2F126225626_o.jpg)